Handle With Care

Oral health professionals must follow safety guidelines to minimize the risk of needlestick injuries.

In 1971, Washington became the first state to legalize the administration of local anesthesia by dental hygienists. Today, 44 states allow dental hygienists to provide local anesthesia.1 Oral health professionals in the United States administer more than 300 million dental cartridges annually, with a well-documented safety record.2–4

With the substantial number of injections administered every year, clinicians must adhere to protocols for the safe handling of needles to prevent needlestick injuries. Needlestick and percutaneous injuries can transmit hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus, and other diseases through blood and bodily fluids.5 Preventing occupational exposures can significantly reduce the possibility of disease transmission. Proper handling, recapping, and disposal techniques are imperative to preventing needlestick injuries.6

PREVENTION STRATEGIES

Basic armamentarium for the administration of local anesthetic agents consists of a sterilizable syringe, the anesthetic cartridge, and a needle. Needles manufactured for dentistry are disposable and have a flexible, tubular stainless steel shaft. Each needle is presterilized with a needle cap or sheath for safety and a seal to ensure sterility. The primary role of the needle cap is to protect the needle from contamination and the clinician from inadvertent injury.

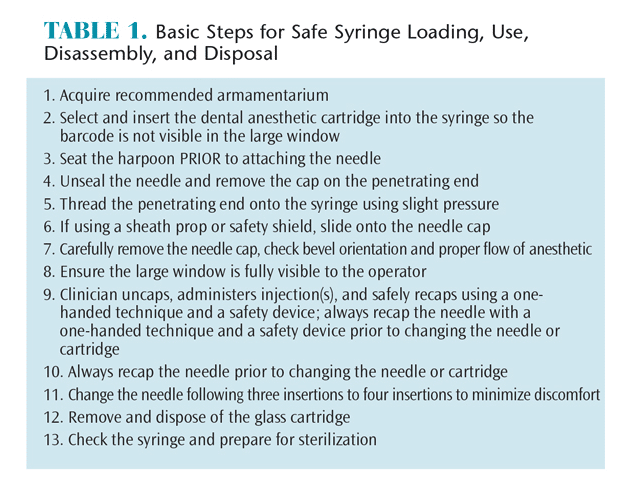

Safe disposal of needles is also important, as 22% of needlestick injuries are caused by improper disposal.7 Used needles should be discarded into sharps containers, which are rigid and puncture-resistant. Once the sharps reach the “full” line, the safety cap should be placed on the container and arrangements made for proper disposal. Table 1 provides tips for safe syringe use.

STANDARD PRECAUTIONS

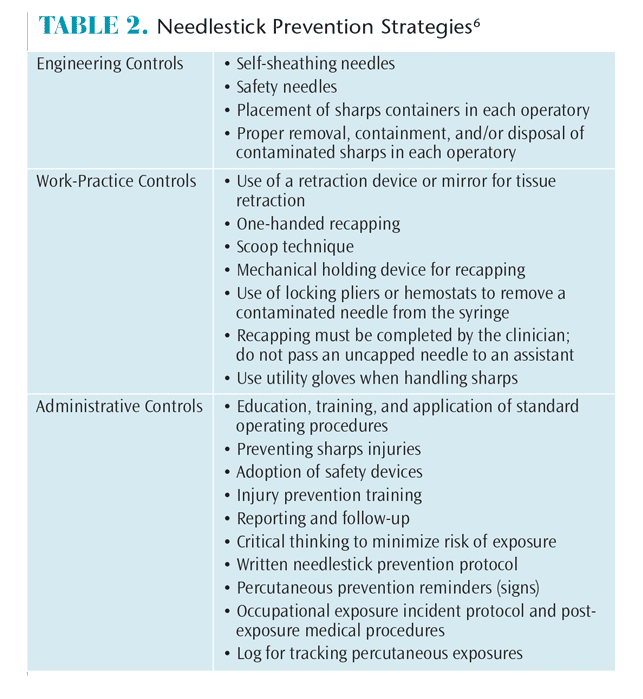

Proper preparation can prevent and minimize complications due to dental needle usage. Standard precautions include engineering controls, work-practice controls, and administrative controls (Table 2).6 Engineering controls are designed to protect workers from hazards, and include placing sharps containers in operatories so clinicians don’t need to transport them to another area and using technology to design safe devices, such as self-sheathing needles and hands-free disposal options.

Work-practice controls refer to procedures that minimize injury in the workplace, such as the safe handling of needles and sharps during syringe assembly, disassembly, and disposal. Using a mirror, tongue blade, or retractor instead of a gloved finger for tissue retraction can limit injuries. Not bending the needle and implementing recapping devices may decrease risk. The one-handed recapping technique—in which a clinician places the cap on a flat surface, removes his or her hand, inserts the tip of the needle into the cap, and presses the cap against an inanimate object to secure into place—is appropriate. The scoop technique is another option and is based on the practitioner placing the cap on a flat surface, removing his or her hand, and then using the needle to “scoop” up the cap. Once the cap has completely covered the needle, the opposite hand is used to fasten the cap onto the needle hub. Locking pliers or hemostats can be used to move the needle from the syringe to an approved container. The majority of injuries occur after use and prior to disposal (eg, recapping and disassembly of used needles).8 An unsheathed needle should never be passed from clinician to assistant for recapping. Adhering to engineering and work-practice controls is the primary method for reducing exposures to blood and bodily fluids from sharp instruments and needles.7

Administrative controls involve annual education and training in proper operating procedures, including mandated infection control protocol. Each office should have a comprehensive written plan for preventing needlestick and sharps injuries. The protocol should describe procedures for identifying, reviewing, and adopting safety devices or practices; injury prevention training; and a mechanism for reporting and providing medical follow-up for percutaneous injuries.9

Administrative controls involve annual education and training in proper operating procedures, including mandated infection control protocol. Each office should have a comprehensive written plan for preventing needlestick and sharps injuries. The protocol should describe procedures for identifying, reviewing, and adopting safety devices or practices; injury prevention training; and a mechanism for reporting and providing medical follow-up for percutaneous injuries.9

The development of safety syringes for use in both dental and medical settings may also improve the handling of needles. These devices have engineering controls that minimize the risk of accidental needlestick injuries. Some designs have a sheath that slides and locks over the needle, while other systems enable a one-handed needle-disposal technique. All new devices require training to ensure their safe use, and they may be costly. An ideal safety needle/syringe system that incorporates all of the features of a conventional syringe has not yet been widely accepted by dental practitioners. The quest for new devices that eliminate or minimize needlestick injuries continues.

CONCLUSION

Until additional safety devices become commonplace in dental operatories, oral health professionals should follow the basic guidelines for safe needle handling. Using the concepts embedded in engineering, work-practice, and administrative controls can reduce the incidence of needlestick injuries. Critical thinking and mindful practice of safe needle handling allows dental hygienists to administer local anesthesia in a safe environment for both practitioners and patients.

REFERENCES

- McGlone P, Watt R, Sheiham A. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. Br Dent J. 2001;190:636–639.

- American Dental Association. Policy on Evidence-Based Dentistry. Available at: ada.org/en/about-the-ada/ada-positions-policies-and-statements/policy-on-evidence-based-dentistry. Accessed March 18, 2015.

- American Dental Association. Evidence-Based Dentistry. Available at: ada.org/en/science-research/evidence-based-dentistry. Accessed March 18, 2015.

- International Ergonomics Association. Definition and Domains of Ergonomics. Available at: iea.cc/whats. Accessed March 18, 2015.

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1604–1612.

- Madhavji A, Araujo EA, Kim KB, Buschang PH. The attitudes, awareness, and barriers towards evidence-based practice in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofac. 2011; 140:309–316.

- Straus SE, Richardson WS, Glasziou P, Haynes RB. Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 3rd ed. New York: Elsevier; 2005.

- Forrest JL, Miller SA, Overman P, Newman MG. Evidence-Based Decision Making: A Translational Guide for Dental Professionals. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

- Rempel D, Lee DL, Dawson K, Loomer P. The effects of periodontal curette handle weight and diameter on arm pain. A four-month randomized controlled trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143: 1105–1113.

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, Michigan: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

- Forrest JL, Miller SA. Evidence-based decision making. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2005;3(9):12.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2015;13(4):16,18.