WHITE BEAR STUDIO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

WHITE BEAR STUDIO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Fluoride Treatment Strategies

Evidence-based guidelines are integral to providing safe and effective recommendations for fluoride use to prevent dental caries.

This course was published in the September 2021 issue and expires September 2024. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the history of using fluoride to prevent dental disease.

- Identify over-the-counter, prescription, and professional fluoride recommendations in the clinical setting.

- Explain recommendations for fluoride therapies based on evidence-based practice guidelines.

In the early 1900s, Frederick McKay, DDS, observed unique brown staining of teeth in his Colorado dental practice.1,2 After years of investigation, McKay found high levels of fluoride in the water supply of affected individuals. Then, in the 1930s, researchers using new technology identified a level of fluoride in drinking water that caused the brown staining.1,2 Throughout these years of research, scientists noted that those with the brown staining on their teeth also experienced much lower levels of dental caries. This brought about study on whether fluoride consumed through water could help decrease community caries rates. Other caries-reducing strategies were also under investigation. In 1945, the American Dental Association (ADA) rejected a hypothesis that vitamin D prevented caries.3 In the same year, the community of Grand Rapids, Michigan, began fluoridating its water supply. The ADA has now been promoting community water fluoridation as safe and effective for more than 70 years. In fact, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers community water fluoridation one of the top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century.4

The decision to fluoridate water supplies was timely because in the 1940s, an estimated 700 million caries lesions were documented among the US population.5 During this time, dental manufacturers began investigating what could be added to toothpaste to decrease caries rates, and in 1956, stannous fluoride was added to toothpaste in the US.5 In the decades since 1956, toothpastes have evolved in the type and amount of fluoride added, and both professional and at-home fluoride products have expanded as evidence continues to support fluoride as a preventive agent and nonsurgical treatment in the management of caries.

Fluoride Use and Recommendations

Oral health professionals have advocated for the use of topical fluoride in efforts to reduce sensitivity, remineralize weakened tooth structure, and prevent caries lesions. The role of fluoride has remained constant for many years; however, the use of fluoride in dentistry continues to evolve, as the evidence continues to shed light on updated strategies and best practices. For instance, many oral health professionals once used fluoride foam for professional treatments. Recently, the ADA released updated guidelines indicating that gel and varnish treatments yielded superior results compared to foam.6

Dental hygiene treatment plans should reflect the patient’s caries risk and existing habits, both of which can be identified through a detailed medical history. Oral health professionals can then tailor their unique treatment plans based on the patient’s assessment. Only then can appropriate recommendations for in-office and at-home fluoride treatments be made. The key in fluoride therapy recommendations remains identifying the correct concentration of fluoride for individual patient need based on caries risk.7

![TABLE 1. Recommendations for Fluoride Products to Reduce Tooth Decay]() At-Home, Over-the-Counter Fluoride Products

At-Home, Over-the-Counter Fluoride Products

All patients, even those at low caries risk, may benefit from over-the-counter (OTC) fluoride toothpaste and community water fluoridation.6 Most OTC dentifrices are between 1,000 ppm and 1,500 ppm fluoride.8 All patients should use fluoride dentifrice at least twice a day (more frequently if caries risk is high or extreme).9 Caries risk is determined by assessing a patient’s habits, history, and experience. Characteristics that increase caries risk include diet containing sugary foods, previous experience with caries, ability to perform oral self-care, medical status (specifically chemotherapy and/or radiation therapies), missing teeth due to caries, and dry mouth.

The ADA’s caries risk assessment forms enable oral health professionals to identify caries risk based on these characteristics. Caries risk is determined based on the highest risk characteristic noted. If the patient exhibits only low risk or no risk characteristics, he or she is at low risk for caries. If the patient has characteristics that put him or her at a low or moderate risk for caries, the caries risk is moderate. If any characteristics identified as high risk are noted, the patient is at high risk for caries.10 Extreme caries risk means the patient is noted as high risk for caries and presents with hyposalivation.9

After eruption of the first tooth, children younger than age 3 should be assisted during toothbrushing, and parents/caregivers should only use a grain-of-rice-size amount of toothpaste.11 Parents/caregivers also need to assist children between the ages of 3 and 6, and should be instructed to only use a pea-sized amount of toothpaste.11 Patients need to be educated on toothbrushing technique tailored to their needs and based on clinical findings. Moreover, oral health professionals should encourage patients to avoid rinsing after toothbrushing so they will receive the optimal benefits of the fluoride toothpaste.11 Rinsing after toothbrushing can minimize fluoride exposure and reduce its beneficial impact on the oral environment.

Patients at moderate risk for caries should use an OTC daily fluoride mouthrinse.9 For example, a patient at moderate caries risk may be taking medications that reduce salivary flow.10 When making a recommendation for an OTC mouthrinse, the patient’s likelihood for compliance needs to be considered. Low potency rinses are used daily whereas higher potency rinses are used weekly.11 Oral health professionals should always tailor recommendations to each patient based on clinical assessments.12 Table 1 provides details on making appropriate recommendations for at-home OTC fluoride regimens.

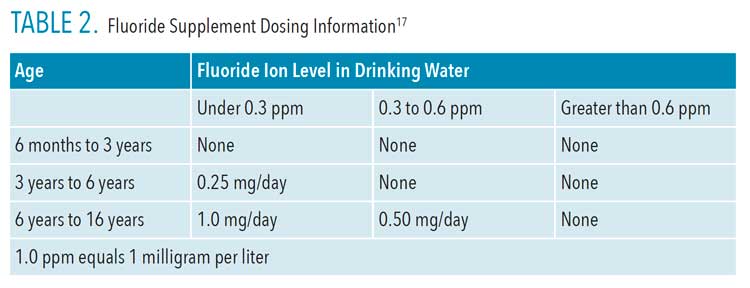

![ABLE 2. Fluoride Supplement Dosing Information]() At-Home, Prescription Fluoride Products

At-Home, Prescription Fluoride Products

Fluoride supplementation should be considered for children and adolescents at high caries risk.8,13 Before prescribing fluoride supplements (drops, tablets), oral health professionals should consider all sources of fluoride consumption. If well water is consumed, the water should be tested to determine ppm fluoride prior to prescribing fluoride supplements.8,14,15 This requires laboratory testing and analysis. Local public health departments can help find a company to test the water.16

When prescribing fluoride, no more than 264 mg (120 mg fluoride ion) should be prescribed per household at one time. Supplements should be taken with water, but not dairy products due to fluoride’s ability to bind with dairy products.11 Providers should follow the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs Dosage Chart when prescribing fluoride supplements (Table 2, page 41).17

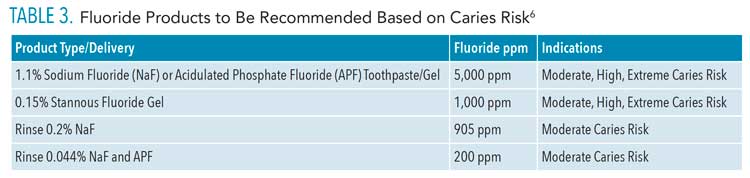

Other types of prescription fluoride include toothpaste/gels and rinses. When caries risk is elevated, clinicians should consider the potential benefits of an at-home, prescription fluoride product. For patients at moderate, high, and extreme caries risk, a prescription fluoride toothpaste should be considered as part of the caries management regimen.9

Table 3 lists several fluoride product types that can be recommended based on patients’ caries risk. For a patient at high caries risk, a twice daily, 5,000 ppm concentration fluoride toothpaste should be recommended. Prescription rinses are also available for those at moderate caries risk. Individuals with high or extreme caries risk should use an antimicrobial rinse. Individuals at extreme caries risk should also use a baking soda rinse to control pH.9

Stannous fluoride gels and rinses are also recommended. While stannous fluoride has a long history of use in dentistry, stabilizing it took some time to perfect.18 With the addition of key ingredients, namely zinc phosphate, stabilization has been improved.19

![TABLE 3. Fluoride Products to Be Recommended Based on Caries Risk]() In-Office, Professional Fluoride Recommendations

In-Office, Professional Fluoride Recommendations

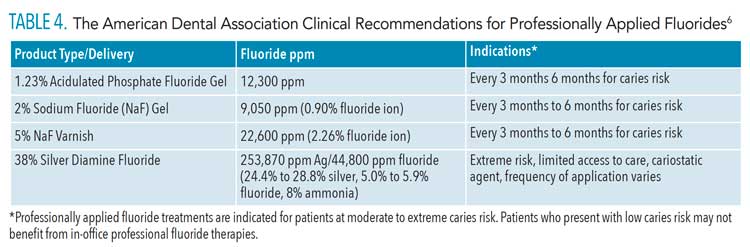

Caries risk assessment tools are key to personalizing all fluoride therapy recommendations, including professional fluoride therapies.20 All fluoride recommendations should be personalized through caries risk assessment tools.20 Table 4 illustrates the ADA’s Clinical Recommendations for Professionally Applied Fluorides.6 This set of recommendations is scheduled to be updated in 2021.

For children younger than age 6, fluoride varnish is the only recommended professionally applied fluoride.6,15 Fluoride mouthrinse should never be recommended to children younger than age 6 due to their limited capacity to expectorate, which could lead to too much fluoride exposure.6,7

The ADA’s guidance supports fluoride varnish treatments every 3 months to 6 months for individuals at risk for dental caries.6 For individuals ages 6 to 18, the guidance supports varnish every 3 months to 6 months or a 1.23 % acidulated phosphate fluoride gel treatment applied for 4 minutes. Although not identified as being “in favor of,” the guidance suggests that “expert opinion” exists in support of fluoride varnish or gel treatments every 3 months to 6 months for individuals older than 18, without explicitly endorsing this recommendation.6

Patients with root exposure (exposed cementum), hyposalivation (reduced salivary flow), or other clinical presentations or behavioral practices that increase the risk of caries should have fluoride varnish applied every 3 months to 6 months.6,21,22

Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) has demonstrated significant results as a cariostatic agent. With antibacterial (silver) and preventive (fluoride) properties, SDF provides secondary prevention in that it arrests decay.7,11 The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) supports the use of SDF in children.23 Additionally, SDF benefits patients with root exposure. A 2018 review of the literature suggests that not only can SDF prevent root caries, but application in areas that have been affected by dental caries can lead to the arresting of the carious lesion.24

The one drawback to SDF is the dark staining left on the area of decay after application, which is caused by the precipitation of silver byproducts.25 The potential for staining should be discussed clearly and thoroughly with the patient and parent/caregiver prior to the procedure.

![TABLE 4. The American Dental Association Clinical Recommendations for Professionally Applied Fluorides]() Caries Risk Assessment to Guide Fluoride Recommendations

Caries Risk Assessment to Guide Fluoride Recommendations

Caries risk assessment tools help clinicians analyze clinical observations, preventive factors, and risk factors, leading to the identification of a patient’s caries risk status. Some caries risk assessment tools are based on age. For instance, the ADA and AAPD offer caries risk forms for children ages 0 to 6/0 to 5, respectively, and age 6 years and older. The AAPD caries risk form classifies caries risk factors as social/biological factors, protective factors, and clinical findings. The ADA states that clinicians should use their judgment on which form to use for 6-year-old patients.9 Both organizations recognize low, moderate, and high caries risk.

Caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA) classifies a patient as extreme or very high risk in the presence of the following:9

- Risk factors are greater than the preventive factors

- Cavitated lesions (advanced carious lesion when there is a break in the surface of the tooth) are present

- Hyposalivation (reduced salivary flow)

- Caries is into the dentin as seen via radiographs

If patients present with disease indicators, such as a new lesion in 3 years for new patients or a new lesion in 1 year for established patients, the risk level is identified as high. If these patients also presented with hyposalivation, they are classified as extreme risk.9

Professional judgment is also important when identifying caries risk level. By assessing each patient’s unique needs, the clinician can develop treatment strategies that support a noninvasive caries management solution. While these guidelines remain the gold standard, oral health professionals should not use them as the only means of determining fluoride treatment recommendations. Clinicians should consider the assessment data—including both preventive and risk factors—to make recommendations that will enhance and improve each patient’s oral health. By explaining how recommendations are developed, patients become involved in the decision-making process, leading to improved patient compliance and outcomes.

References

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The Story of Fluoridation. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/health-info/fluoride/the-story-of-fluoridation. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Fluoridation of Drinking Water to Prevent Dental Caries. Available at: cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4841a1.htm. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- Hujoel P. Historical perspectives on advertising and the meme that personal oral hygiene prevents dental caries. Gerontology. 2019;36:36–44.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Water Fluoridation. Available at: cdc.gov/fluoridation/index.html. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- Crest. History of Toothpaste. Available at: https://crest.com/en-us/oral-health/why-crest/faq/history-toothpaste. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo T, et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1279–1291.

- Bowen DM, Pieran JA. In: Darby and Walsh Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 5th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2020.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other Fluoride Products. Available at: cdc.gov/fluoridation/basics/fluoride-products.html. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- Featherstone JDB, Alston P, Chaffee BW, Rechmann P. Caries management by risk assessment: An update for use in clinical practice for patients aged 6 through adult. Available at: oralhealthsupport.ucsf.edu/publications/caries-management-risk-assessment-cambra-update-use-clinical-practice-patients-aged-6. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form. Available at: .ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/topic_caries_over6.pdf?la=en. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- Boyd LD, Mallonee LF, Wyche CJ, Halaris, JF. Wilkins’ Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 13th ed. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett; 2021:573–593.

- Reshetnyak VY, Nesterova OV, Admakin OI, et al. Evaluation of free and total fluoride concentration in mouthwashes via measurement with ion-selective electrode. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:1–8.

- Fontana M, Eckert GJ, Keels MA, et al. Fluoride use in health care settings: Association with children’s caries risk. Adv Dent Res. 2018;29:24–34.

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Fluoride toothpaste use for young children. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:190–191.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on use of fluoride. Available at: aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/p_fluorideuse.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Water Fluoridation, Private Wells. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/faqs/wellwater.htm. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- Rozier RG, Adair S, Graham F, et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations on the prescription of dietary fluoride supplements for caries prevention: a report of the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:1480–1489.

- Vogell S, Burke M, Marinakos G, Quintanilla L. The new generation of stannous fluoride. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2021;19(5):14–16.

- Myers C, Pappas I, Makwana E, et al. Solving the problem with stannous fluoride. JAMA. 2019;150(4 Suppl): S5–S13.

- Featherstone JDB, Crystal YO, Alston P, et al. A comparison of four caries risk assessment methods. Frontiers in Oral Health. 2021;2:1–13.

- Mascarenhas AK. Is fluoride varnish safe? J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152:364–368.

- Picano L. Fluoride varnishes: What is the difference, and which one is best? Available at: dentaleconomics.com/science-tech/cosmetic-dentistry-and-whitening/article/14173399/fluoride-varnishes-what-is-the-difference-and-which-one-is-best. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Chairside guide: silver diamine fluoride in the management of dental caries lesions. Available at: aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/R_ChairsideGuide.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2021.

- Oliveira BH, Cunha-Cruz J, Rajendra A, Niederman R. Controlling caries in exposed root surfaces with silver diamine fluoride: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149:671–679.

- Crystal YO, Niederman R. Evidence-based dentistry update on silver diamine fluoride. Dent Clin North Am. 2019;63:45–68.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2021;19(9):40-43.