Erosive Tooth Wear

Dental hygienists are well positioned to help patients treat and prevent the effects of this common oral health problem.

Erosion and tooth wear are increasingly common threats to oral health as the consumption of acidic beverages continues to grow. The acid pH of a soft drink, for example, is strong enough to dissolve an eggshell.1 This is similar to what occurs when the crystalline tooth structure is attacked by acidic forces. Once the outer layer of enamel has broken down, teeth are not able to rebuild a new enamel surface. When the surface structure is compromised, secondary dentin is more likely to form, and the tooth eventually becomes less responsive to various stimuli.

The loss of tooth structure puts oral health at risk and negatively impacts quality of life by causing dentinal hypersensitivity. The availability of a new measuring and recording tool and the advent of the person-centric approach to care may help dental hygienists improve outcomes for the many patients who experience dentinal hypersensitivity.

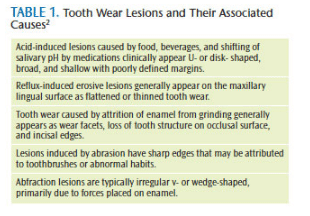

Dentinal hypersensitivity describes a decrease in enamel thickness, thereby initiating a potential sensation through a nerve fibril encased in the dental tubule. Table 1 lists tooth wear lesions and their associated causes.2 A leading origin of dentinal sensitivity is erosion—a form of tooth wear caused by repeated short exposures of insults, such as acids. These acids may be from intrinsic (gastroesophageal reflux disease, bulimia, and anorexia) or extrinsic sources (diet, drug use, and hygiene factors), in which the combined role of erosion and abrasion may increase wear.3–5 Erosion is also dependent on the host susceptibility, such as low enamel quality, thin enamel surface, salivary factors, gingival recession, exposure of cervical dentin, and the acidity of the oral environment.6 In this manuscript, the term tooth wear will include noncarious cervical lesions (NCCL).2 There are four distinct factors that contribute to tooth wear: erosion (loss of tooth structure caused by acids); attrition (mechanical loss of tooth structure caused by tooth to tooth contact); abrasion (mechanical loss of tooth structure caused by contact with other materials); and abfraction(dynamic tooth wear caused by the combination of compressive forces).2,7

Dentinal hypersensitivity describes a decrease in enamel thickness, thereby initiating a potential sensation through a nerve fibril encased in the dental tubule. Table 1 lists tooth wear lesions and their associated causes.2 A leading origin of dentinal sensitivity is erosion—a form of tooth wear caused by repeated short exposures of insults, such as acids. These acids may be from intrinsic (gastroesophageal reflux disease, bulimia, and anorexia) or extrinsic sources (diet, drug use, and hygiene factors), in which the combined role of erosion and abrasion may increase wear.3–5 Erosion is also dependent on the host susceptibility, such as low enamel quality, thin enamel surface, salivary factors, gingival recession, exposure of cervical dentin, and the acidity of the oral environment.6 In this manuscript, the term tooth wear will include noncarious cervical lesions (NCCL).2 There are four distinct factors that contribute to tooth wear: erosion (loss of tooth structure caused by acids); attrition (mechanical loss of tooth structure caused by tooth to tooth contact); abrasion (mechanical loss of tooth structure caused by contact with other materials); and abfraction(dynamic tooth wear caused by the combination of compressive forces).2,7

TOOL FOR MEASURING TOOTH WEAR

Erosion reduces structural integrity, pulpal vitality, and esthetics. Men typically experience erosion more often than women.8 Differences exist in the diagnosis and assessment between scales used to record prevalence information and data across different studies may not be entirely comparable.9

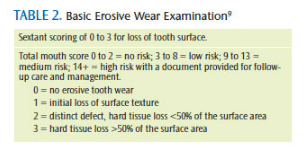

In 2008, Bartlett et al10 published the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE), which ranks tooth wear (by sextant from 0 to 3), summing up the total area of tooth loss (on a scale that goes to 18), and ranking the extent of risk from none to high (Table 2). Once the determination of risk has been made, a support guide helps clinicians educate patients about individual risk scores and informs them about intrinsic, extrinsic, and susceptibility risk factors. Designed as a tool to help develop a standardized index of tooth wear, the BEWE may help oral health professionals place more emphasis on erosive wear and assist their patients in preventing or effectively managing this threat to oral health.10

PERSON-CENTRIC CARE

Person-centric care is inclusive of both disease management and health. A person spends a very short time as a “patient,” and the term describes the person as subservient to treatment, prevention, and management. The evolution of patient-centered to person-centered care is a shift from a disease management approach to a health-oriented model. Person-centric care involves engaging individuals in the context of their physical and social environments to make self-determined choices.11 Individuals maintain ultimate responsibility for their own health. In disease treatment models, patients are passive recipients of care, with providers making decisions about their needs.

Dental hygienists have the unique opportunity to serve as oral health coaches for people experiencing dental erosion. As guides, dental hygienists may describe and educate people about prevention, and explain various treatment strategies from which patients can choose. A thorough assessment must first be conducted to identify patient needs.

Patient engagement includes initiating a conversation about oral care habits, where information may be shared between the provider and patient. For example, when dental hygienists explain how a desensitizing toothpaste works, they can reference two methods of action:

- Potassium ion navigates the dentinal tubule to reach the cell body (odontoblast) within the pulp to depolarize the nerve. Subsequent use of the toothpaste keeps the nerve depolarized to limit nerve transmission upon tooth stimulation.

- Potassium nitrate occludes the dentinal tubules on the tooth surface.

The person’s responsibility is to adapt his or her oral care routine to prevent further breakdown and deterioration of enamel and/or dentin. If a person maintains the integrity of the tooth, the viability of the pulp is maintained and further breakdown is prevented. Apoptosis, or programmed cell death related to overstimulation, can be limited. This is important because enamel is irreplaceable, and it is necessary to protect the pulp from overstimulation. If the pulp develops secondary dentin, it reduces the tooth’s ability to respond to sensation and may make the tooth more susceptible to further pulpal breakdown.

ASSESSMENT OF TOOTH WEAR

The first step in guiding person-centric care is the needs assessment, where an oral screening is conducted and tooth wear is identified. The degree to which the various factors interplay should be assessed at an individual level by measuring the depth and width of the tooth wear and asking about sensitivity. Using a pain scale may be helpful.12 In addition, clinicians may benefit from using a tool like the BEWE to screen and track tooth wear. Bartlett10 recommends screening every 2 years for low-risk individuals and every 6 months to 12 months for medium- to high-risk individuals. Progression of wear is measured by impressions, study casts, images, or depth and width of lesions.

PREVENTION OF NONCARIOUS CERVICAL LESIONS

Until the underlying cause of tooth wear is controlled, progression will likely continue. According to Percie et al,13 there is a lack of evidence on how best to prevent NCCLs, and further study is needed on effective preventive strategies. The primary goal is to eliminate the source of the erosion, such as the consumption of acidic foods and beverages (eg, sports drinks, energy drinks, juice, and soft drinks).14

Anticipatory guidance for individuals at risk of tooth wear involves a thorough dietary analysis and medical and dental histories to determine internal and external acidic sources, as well as to identify susceptibility. Nutritional counseling is beneficial to address external sources of acids in the diet. Additionally, harm reduction strategies, such as antacid rinse to increase pH in the mouth after an acidic exposure, may help reduce enamel softening after vomiting.15 To reduce abrasion, toothbrushing should be avoided after an acidic challenge. Toothbrushing pressure is also associated with increased risk of tooth wear.16 Reducing pressure applied with the toothbrush and recommending soft toothbrushes and low abrasive dentifrices may help reduce risk. Products are now available with sensors to indicate when excess pressure is applied during brushing.

Traditional preventive strategies focus on preservation of tooth structure through mineralization. Fluoride therapy may be recommended. There are numerous products available to reduce sensitivity including, but not limited to, fluoride toothpaste, fluoride rinses, in-office fluoride treatments (gel or varnish), calcium phosphate technologies for use in the dental office as well as at home, 5% glutaraldehyde and 35% hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), bonding adhesives, arginine-calcium carbonate in-office paste, potassium nitrate toothpastes, and potassium oxalate strips. Educational approaches include improved toothbrushing techniques, comprehensive oral hygiene instructions, recommendation of improved oral hygiene routine, and prescription of an occlusal guard to reduce occlusal stresses.

MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT OF TOOTH WEAR

Tooth wear is challenging to treat (restoration failure has been repeatedly cited in the literature,)17 and there remains controversy over whether it needs to be treated.18 Bartlett et al5 recommends treatment only in the high-risk groups. Traditionally, glass-ionomer-based materials were the treatment of choice when tooth wear required intervention. A recent review of the literature, however, suggests that resin-based composite (RBC) is indicated due to its excellent esthetic properties and good clinical performance.17 Esthetic consideration is another reason people seek treatment for tooth wear. Clinically significant issues around these lesions are dentinal hypersensitivity, plaque retention, structural integrity of the area, and pulpal vitality.

To address each person’s needs—and in order to determine the best treatment options—clinicians must consider personal and environmental characteristics. A recent study by the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning (PEARL) Practice-Based Translational Network looked at using person-centric care in patients with tooth wear and dentinal hypersensitivity.18 PEARL studied the uses of a potassium nitrate dentifrice, RBC restoration, and sealant in a randomized comparative effectiveness study of NCCLs where patients reported baseline sensitivity of 3 or higher (on a scale of 0 to 10). The 6-month study found that sealants and RBC restoration treatments proved equally effective in reducing hypersensitivity for most participants, and that the relative ease of application of the sealant compared with that of a restoration might save considerable time in treating NCCLs. In addition, the use of a dentifrice to reduce hypersensitivity was not as effective as the sealant or restoration.18

In low-risk cases, experts recommend less invasive preventive methods rather than treatment with irreversible dental procedures.5 Dental hygienists are qualified to provide sealants for prevention of occlusal caries. Applying sealants for individuals with painful NCCLs is an additional treatment option that may reduce time and cost to patients. State board interpretation for the scope of practice may vary, and dental hygienists should check with their state boards of dentistry to ensure this is within their purview. In high-risk sensitivity cases (as determined by the BEWE score), restorative therapies, such as RBC, may be indicated.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists are uniquely positioned to reduce the burden of oral disease by screening and educating the public about tooth wear. With myriad educational interventions and treatment strategies available, dental hygienists can make a difference in reducing the risk of tooth wear and erosion and effectively addressing dentinal hypersensitivity.

REFERENCES

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Eggstra Healthy Teeth: Winning Experiment Procedures from the NIH LAB Challenge. Available at: drugabuse.gov/sites/default/ files/files/GoldblattEggstraHealthyTeeth.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2014.

- Terry DA, McGuire MK, McLaren E, Fulton R, Swift EJ Jr. Perioesthetic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of carious and noncarious cervical lesions: Part I. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2003;15:217–232.

- Moazzez R, Bartlett D, Anggiansah A. Dental erosion, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and saliva: how are they related? J Dent. 2004;32:489–494.

- Brown RE, Morisky DE, Silverstein SJ. Meth mouth severity in response to drug-use patterns and dental access in methamphetamine users. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2013;41:421–428.

- Bartlett DW, Shah P. A critical review of noncarious cervical (wear) lesions and the role of abfraction, erosion, and abrasion. J Dent Res. 2006;85:306–312.

- Wood I, Jawad Z, Paisley C, Brunton P. Noncarious cervical tooth surface loss: a literature review. J Dent. 2008;36:759–766.

- Grippo JO. Noncarious cervical lesions: the decision to ignore or restore. J Esthet Dent. 1992;(Suppl 4):55–64.

- McGuire J, Szabo A, Jackson S, Bradley TG, Okunseri C. Erosive tooth wear among children in the United States: relationship to race/ethnicity and obesity. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:91–98.

- Bartlett D, Phillips K, Smith B. A difference in perspective–the North American and European interpretations of tooth wear.Int J Prosthodont. 1999;12:401–408.

- Bartlett D, Ganss C, Lussi A. Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE): a new scoring system for scientific and clinical needs. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12(Suppl 1):S65–S68.

- Curro FA, Robbins DA, Millenson ML, Fox CH, Naftolin F. Person-centric clinical trials: an opportunity for the good clinical practice (GCP)-practice-based research network. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;53:1091–1094.

- Orchardson R, Gillam DG. Managing dentin hypersensitivity. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:990–998.

- Pecie R, Krejci I, Garcia-Godoy F, Bortolotto T. Noncarious cervical lesions–a clinical concept based on the literature review. Part 1: prevention. Am J Dent. 2011;24:49–56.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Acidified and Low-Acid Canned Foods: Approximate pH of foods and good products. Available at: foodscience.caes.uga. edu/ extension/documents/fdaapproximate ph offoodslacf-phs.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2014.

- Turssi CP, Vianna LM, Hara AT, do Amaral FL, França FM, Basting RT. Counteractive effect of antacid suspensions on intrinsic dental erosion. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012;120:349–352.

- Brandini D, de Sousa A, Trevisan C, et al. Noncarious cervical lesions and their association with toothbrushing practices: in vivo evaluation. Oper Dent. 2011;36:581–589.

- Lee WC, Eakle WS. Stress-induced cervical lesions: review of advances in the past 10 years. J Prosthet Dent. 1996;75:487–494.

- Veitz-Keenan A, Barna JA, Strober B, et al. Treatments for hypersensitive noncarious cervical lesions: a Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning (PEARL) Network randomized clinical effectiveness study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:495–506.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2014;12(9):38,40,42.