SSSSS1GMEL/ISTOCK/THINKSTOCK

SSSSS1GMEL/ISTOCK/THINKSTOCK

Ensure the Safety of Dental Treatment Water

Appropriate methods to control biofilm formation and monitor water quality must be implemented to safeguard patients.

This course was published in the March 2017 issue and expires March 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the effects of biofilm formation in dental unit waterlines.

- Identify the infections associated with dental treatment water.

- List the standards for minimum water quality in dental offices.

- Explain procedures for effectively managing dental treatment water quality.

INTRODUCTION

Dentistry has long been on a quest for best infection control practices regarding dental unit waterline (DUWL) treatment in order to maintain safety. Exposure to poor water quality can pose health risks for patients during treatment, as well as clinicians due to aerosol exposures. Noted most recently, two pediatric dental clinics experienced multiple outbreaks of Mycobacterium abscessus found in their DUWLs. This article reviews biofilm formation in DUWL tubing, minimum standards for safety, and various methods for DUWL treatment.

A division of Cantel Medical, Crosstex International manufactures a wide array of infection prevention and control products for the health care industry. Founded in 1953, Crosstex is a recognized global leader for its portfolio of waterline treatment, biological monitoring, nitrous oxide, sterility assurance packaging, and personal protection equipment. The Crosstex mission is to protect, innovate, and educate.

Leann Keefer, RDH, MSM

Director, Corporate Education and Professional Relations

Crosstex International

Water is essential to the practice of dentistry and is used for a variety of functions—from irrigating surgical sites to providing lavage during ultrasonic instrumentation. More than five decades have passed since the scientific literature first reported that the tubing delivering water to dental devices has a strong tendency to develop biofilm, resulting in patient exposure to water with high levels of microbial contamination.1 Biofilm can cause infection among dental patients, and exposes oral heath professionals to aerosolized bacteria that may cause illness.2–6

Water in dental devices may not be of appropriate quality for health care procedures, so the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed guidelines related to dental unit water quality. The CDC recommends that dental unit waterlines (DUWLs) adhere to the same standards for safe drinking water as set forth by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of less than or equal to 500 colony forming units (CFU) per milliliter. Many advances have been made in both the understanding of DUWL biofilm and the methods for controlling and monitoring water quality in dentistry.

BIOFILM FORMATION

Biofilm forms in DUWLs over a relatively short time if there is no waterline treatment. Water from municipal systems (tap water) contains small amounts of bacteria and other microorganisms. When the water enters the dental unit, it must pass through a complex system of small tubing within the dental unit. Some of these organisms from the source water collect to form a heterogeneous population of organisms on the lining of the dental water tubing.3,7,8 Over time, a biofilm matrix forms that provides a nutrient-rich environment conducive to bacteria colonization; similar to the biofilm that forms plaque on teeth. As water passes over the biofilm, it becomes more heavily infused with bacteria and other microorganisms. By the time the water exits the handpiece, air/water syringe, and/or ultrasonic scaler, it may contain hundreds of thousands of heterotrophic bacteria in a single milliliter of water, some of which may be human pathogens.7 Simply using bottled water, distilled water, or sterile water is not effective in preventing biofilm formation in dental water tubing. A comprehensive treatment program must be implemented in order to maintain acceptable water quality.

INFECTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH DENTAL TREATMENT WATER

Little is known about disease outbreaks related to exposure to microorganisms in dental water. This may be due to the low risk associated with bacteria commonly found in untreated lines or because identifying the connection between dental exposure and infection that arises days after the patient has received dental treatment is difficult. Several incidents where the connection between infection and exposure to bacteria in dental treatment water, however, have been confirmed. For many years, it was proposed that the risk of infection was not significant to individuals with healthy immune systems, as the types of bacteria commonly identified in DUWLs, such as Legionella pneumophila and Pseudomonas, were thought to pose a risk only to immunosuppressed individuals.2,9Two recent outbreaks affecting numerous children have demonstrated that the bacteria found in untreated DUWLs may cause illness in patients with healthy immune systems.

In 2015, 20 children were admitted to hospitals in Georgia with infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus. All affected children had undergone pulpotomy treatments in the same dental clinic. The CDC determined that the source of bacterial contamination was untreated DUWLs with biofilm that had become colonized with M. abscessus.10 The affected children became severely ill and required hospitalization, lasting from 1 day to 17 days. Of the affected children, 17 required surgical excision.

In 2016, another cluster of children experiencing infections caused by M. abscessus emerged, this time in Anaheim, California. Although the CDC has not been involved in the Southern California incident, media outlets have reported that the infections are connected to contaminated water in a children’s dental clinic where the children were all treated.11–13 As many as 58 children developed M. abscessus infections after receiving pulpotomy treatments at the clinic.

The first documented case of infection linked to contaminated dental water was reported in 1987.14 In this case, two patients were diagnosed with post-operative infections. The bacteria isolated from the wound site infections were Pseudomonas aeruginosa—the same bacteria isolated from the dental unit water supply. The first report of a death associated with dental water contamination occurred in Italy, when an elderly woman was hospitalized and later died from Legionnaires’ disease. Because the patient had not been very active in the days leading to her illness, it was possible to determine her exposure occurred during a dental visit.15

With mounting evidence of not only waterline contamination, but also illnesses associated with contaminated dental treatment water, oral health professionals must use a treatment method with demonstrated effectiveness to control biofilm in DUWLs. In addition to treatment, water quality should be routinely monitored to ensure that the treatment is being applied properly and is effective.16

WATER QUALITY FOR DENTAL PROCEDURES

Standards for safe drinking water quality are established by the EPA, the American Public Health Association (APHA), and the American Water Works Association (AWWA).17 These standards set limits for heterotrophic bacteria of ≤ 500 CFU/mL of drinking water. Thus, the number of bacteria in water used as a coolant/irrigant for nonsurgical dental procedures should be as low as reasonably achievable and, at a minimum, ≤ 500 CFU/mL—the regulatory standard for safe drinking water established by the EPA and APHA/AWWA.6

Since 2003, the CDC has recommended that all dental units use systems to provide output treatment water to meet drinking water standards (≤ 500 CFU/mL of heterotrophic water bacteria) for nonsurgical procedures.18 The CDC further clarified that independent reservoirs—or water-bottle systems—alone are not sufficient and should be combined with commercial products and devices that can improve the quality of water used in routine dental treatment. The CDC recommends consulting the dental unit manufacturer as well as the product or device used to control biofilm, for appropriate water maintenance methods and recommendations for monitoring dental water quality (Table 1).6,16

During surgical procedures, the CDC recommends the use of only sterile solutions as coolants/irrigants in an appropriate delivery device, such as a sterile bulb syringe, sterile tubing that bypasses DUWLs, or sterile single-use devices. The CDC’s Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003 define an oral surgical procedure as “involving the incision, excision, or reflection of tissue that exposes the normally sterile areas of the oral cavity. Examples include biopsy, periodontal surgery, apical surgery, implant surgery, and surgical extractions of teeth (eg, removal of erupted or nonerupted tooth requiring elevation of mucoperiosteal flap, removal of bone or section of tooth, and suturing, if needed).”6,16

Any sterile water/coolant system or device marketed to improve dental water quality must be cleared for market by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

MANAGING WATER QUALITY

The CDC recommends discharging water and air from dental devices that are connected to the DUWL system and that enter the patient’s mouth (eg, handpieces, ultrasonic scalers, air/water syringes) for a minimum of 20 seconds to 30 seconds after each patient.6,18 This procedure is intended to physically flush out patient material (eg, oral microorganisms, blood, saliva) that might have entered the turbine, air, or waterlines. Flushing alone does not affect biofilm in waterlines or reliably improve the quality of water used during dental treatment.19,20

In order to achieve the CDC recommended value of ≤ 500 CFU/mL of water, other strategies must be employed. Examples of commercial devices and procedures include:

- Self-contained water systems (eg, independent water reservoir) combined with chemical treatment (eg, periodic or continuous chemical germicide treatment protocols)

- Systems designed for single-chair or entire-practice waterlines that purify or treat incoming water to remove or inactivate microorganisms

Chemical products remove, inactivate, or prevent biofilm formation. Chemical treatments are either continuously infused into or are intermittently added to the dental unit water. It may be necessary to remove biofilm in the DUWLs using a shock treatment before implementing a chemical treatment product. Beyond initial shocking of DUWLs, the specific chemical treatment product manufacturer should provide instructions for routine or periodic shocking of the lines.

Two types of treatment systems are available: treatment cartridges that release an active ingredient that disinfects and filter devices that remove solid particles from water. The treatment cartridge is connected to the dental unit’s existing water bottle pickup tube. Treatment cartridges need to be replaced at scheduled intervals, according to the product-specific manufacturer’s instructions. Filter devices are installed in the waterline, between the DUWL and the dental instrument (eg, dental handpiece, air/water syringe, etc). The filter does not affect biofilm in waterlines, but removes microorganisms as the water exits the waterline through the filter to the dental instrument. Filters must be periodically replaced, with the frequency depending on the amount of biofilm in the waterlines and the manufacturer’s instructions. They may or may not remove endotoxin.

DUWL treatment products and devices are regulated by either the FDA or the EPA. Continuous chemical treatment products, systems, and filters designed for DUWL treatment are regulated by the FDA. Intermittent chemical treatment products are registered with the EPA as cleaners or disinfectants for DUWL treatment.

The dental unit manufacturer should be consulted to determine the compatible methods, products, and devices to maintain the quality of dental water in the specific dental unit(s).6,16 For other dental devices, such as ultrasonic scalers with independent water reservoirs, consult the manufacturer of the device that uses water for instructions and recommended products to control biofilm in the waterlines.

Most new dental units in the US have a separate water reservoir. Using a separate water reservoir system enables the use of water other than the local municipal water supply. In addition to maintaining better control over the quality of the source water used in patient care, it eliminates interruptions in dental care when “boil-water” notices are issued by local health authorities. The separate water reservoir—even when using distilled or sterile water—does not, however, prevent biofilm development in DUWLs. In order to achieve the CDC recommended water quality for nonsurgical dental procedures, separate water reservoirs must be combined with another approach, such as periodic or continuous chemical treatment or filters or centralized water treatment system.6,16

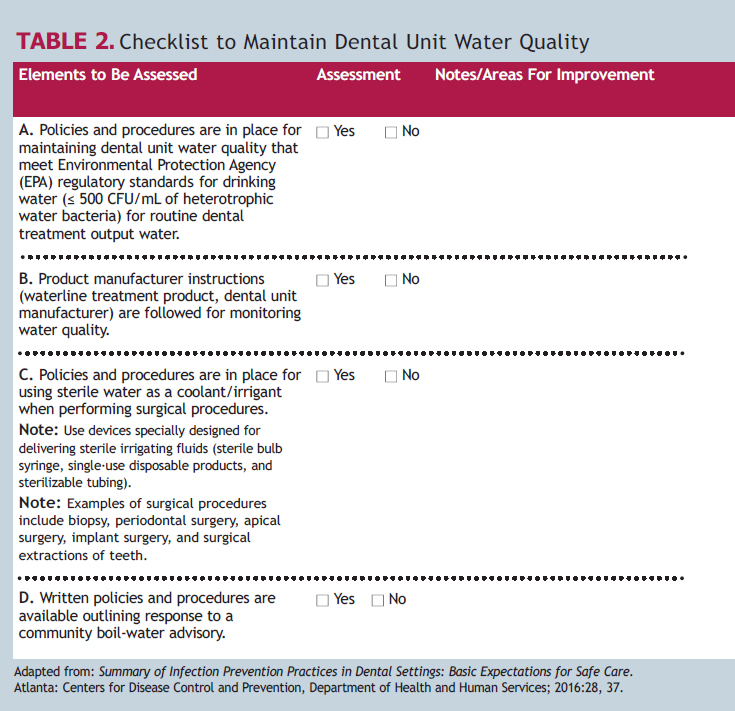

Critical elements of a successful DUWL treatment approach include training of oral health professionals in site-specific DUWL protocols and monitoring compliance. Clinicians should follow the manufacturer-specific directions and instructions for use for all commercial products and devices. The staff members responsible for maintenance of independent reservoir bottles must handle the bottles with clean gloves, and follow the manufacturer instructions for cleaning and aseptically managing the bottles. The CDC’s 2016 Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings contains a two-part checklist to assess compliance with the CDC 2003 recommendations. Table 2 is adapted from the CDC document, and provides assessment items for both the site-specific policies and procedures for managing dental water quality and practices to ensure compliance.

QUALITY ASSURANCE

Instituting a waterline treatment protocol is an important first step in controlling the quality of the output water to dental devices. However, routine monitoring through water quality testing may be necessary to ensure that the treatment is working properly and that oral health professionals are successfully performing the treatment. The manufacturer’s instructions for use should be the first document reviewed when implementing a water treatment program. The manufacturer of the water treatment product should determine whether routine monitoring is indicated and, if so, at what frequency.

Several types of waterline testing kits are available. Some involve the collection of water samples, which are then placed in a shipping box with ice and returned to a laboratory for analysis. Direct-read tests provide results after the collection of water sample in the dental office. The American Dental Association provides a list of testing devices and services but does not validate the accuracy of such methods. Not all testing methods are reliable and accurate.21,22 Oral health professionals should consult the manufacturer of their dental treatment product regarding recommended test methods and frequency.

The lack of awareness regarding the CDC’s recommendations on dental unit water quality, including monitoring of dental unit water, was reported in a 2008 survey conducted by the CDC’s Division of Oral Health. The CDC surveyed a stratified random sample of 6,825 US dentists. The survey aimed to identify factors associated with implementation of the first four practices recommended in the CDC’s Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003. Only one dentist per practice was chosen for the survey. The response rate was 49%.23

One of the four CDC-recommended infection control practices surveyed was whether a single water system was implemented for each dental unit and if the water quality had been evaluated at least once over the past year.23 While the CDC recommends that dental practices monitor their water quality, it does not provide guidelines for the frequency of monitoring.16 The CDC does, however, suggest that dental practices work with the dental unit/water delivery system manufacturer to ascertain the most effective strategy for ensuring acceptable water quality.23

The survey found that approximately 62% of surveyed practices used separate DUWL systems, with 40.2% responding that they monitored the water quality at least once per year. Figure 1 provides the percentages that represent the frequency of dental unit water quality monitoring reported by those practices that used separate DUWL systems.

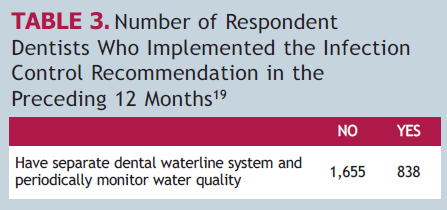

Of the practices that participated in the survey, approximately 33% utilized separate water systems and monitored water quality at least once per year. On the other hand, 32% reported they did not use separate water systems nor did they monitor water quality (Table 3).23

These results demonstrate the need to increase awareness of the CDC recommendations to control the quality of dental unit water. Once aware, oral health professionals must take steps to control the quality of the dental unit water, including following the CDC recommendations for dental unit water quality for nonsurgical and surgical dental procedures; abiding by the manufacturer’s instructions for use for all products and devices; and evaluating compliance and periodically monitoring the quality of the dental unit water.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals, professional organizations, dental educators, and manufacturers/distributors of products and devices to manage dental unit water quality play important roles in facilitating awareness of the importance of clean DUWLs and promoting compliance with CDC recommendations for dental unit water quality. Failure to commit to ensuring the safety of dental treatment water puts patient health at risk.

REFERENCES

- Blake GC. The incidence and control of bacterial infection in dental spray reservoirs. Brit Dent J. 1963;115:413–416.

- Atlas RM, Williams JF, Huntington MK. Legionella contamination of dental-unit waters. Appl Environ Microbiol.1995;61:1208–1213.

- Walker JT, Bradshaw DJ, Bennett AM, Fulford MR, Martin MV, Marsh PD.. Microbial biofilm formation and contamination of dental-unit water systems in general dental practice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3363–3367.

- Challacombe SJ, Fernandes LL. Detecting Legionella pneumophila in water systems: a comparison of various dental units. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:603–608.

- Coleman DC, O’Donnell MJ, Shore AC, Russell RJ. Biofilm problems in dental unit waster systems and its practical control. J App Microbiol. 2009;106:1424–1437.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Questions and Answers on Dental Unit Water Quality. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/questions/dental-unit-water-quality.html. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- Mills SE. The dental unit waterline controversy: defusing the myths, defining the solutions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131: 1427–1441.

- Lal S, Pearce M, Achilles-Day UEM, et al. Developing an ecologically relevant heterogeneous biofilm model for dental-unit waterlines. Biofouling. 2017;33:75–87.

- Lenz AP, Williamson KS, Pitts B, Stewart PS, Franklin MJ. Localized gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4463–4471.

- Peralta G, Tobin-D’Angelo M, Parham A, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus infections among patients of a pediatric dentistry practice—Georgia, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:355–356.

- Ross E. Infection outbreak shines light on water risks at dentists offices. Available at: npr.org/sections/health-shots/ 2016/09/30/495802487/infection-outbreak-shines-light-on-water-risks-at-dentists-offices. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- Kravarik J. Bacteria in dentist’s water sends 30 kids to hospital. CNN. Available at: cnn.com/2016/10/11/health/california-dental-water-bacteria. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- Rocha V, Lozano C. Orange County children’s dental clinic closed after bacteria found in new water system. Los Angeles Times. December 17, 2016.

- Martin MV. The significance of the bacterial contamination of dental unit water systems. Br Dent J. 1987;163:152–154.

- Ricci ML, Fontana S, Pinci F, et al. Pneumonia associated with a dental unit waterline. Lancet. 2012;379:684.

- Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations, 1999: List of Contaminants. Available at: epa.gov/safewater/mcl.html. Accessed February 17, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended infection-control practices for dentistry, 1993. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993;42:1–12.

- Williams JF, Johnston AM, Johnson B, Huntington MK, Mackenzie CD. Microbial contamination of dental unit waterlines: prevalence, intensity and microbiological characteristics. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:59–65.

- Williams HN, Johnson A, Kelley JI, et al. Bacterial contamination of the water supply in newly installed dental units. Quintessence Int. 1995;26:331–337.

- Porteous N, Sun Y, Schoolfield J. Evaluation of 3 dental unit waterline contamination testing methods. Gen Dent. 2015;63:41–47.

- Momeni SS, Tomline N, Ruby JD, Dasanayake AP. Evaluation of in-office dental waterline testing. Gen Dent.2012;60:142–147.

- Cleveland J, Foster M, Barker L, et al. Advancing infection control in dental care settings: Factors associated with dentists’ implementation of guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:1127–1138.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2017;15(3):37-42.