EDWARDOLIVE/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

EDWARDOLIVE/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Endodontic Diagnosis for the Dental Hygienist

Endodontic diagnosis and diagnostic techniques may not be familiar to dental hygienists but their use can improve patient flow, efficiency, and outcomes.

This course was published in the April 2018 issue and expires January 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the role of dental hygienists in endodontic identification and diagnosis.

- Define endodontic disease.

- Identify the testing methods used in endodontic diagnosis.

Dental hygienists are often the first clinicians to examine the oral cavity and review patient radiographs. Of course this varies in every practice setting, but charting existing or potential endodontic disease is as critical as charting caries, alveolar bone loss, pocket formation, and gingival inflammation, as well as any other oral signs of disease or injuries.

Dental practice acts vary among jurisdictions, as do the scopes of practice. While the dental hygienist may not be able to make a legal diagnosis regarding endodontic disease, he or she can perform endodontic diagnostic testing for review by a supervising dentist or endodontist. The technique required is well within a dental hygienist’s skill set. The ability to identify whether endodontic disease is present benefits patients, as well as dental practices, and can help focus attention on immediate and long-term needs.

TESTING METHODS

There is a diversity of opinions regarding testing methods and their respective importance in endodontic diagnosis. Currently, no single pulp testing technique can reliably diagnose all pulpal conditions, neither has one been proven to be superior in all aspects.3Nonetheless, developing a pulpal and periapical endodontic diagnosis is necessary before initiating (or not initiating) endodontic treatment. Generally, determining which tooth requires endodontic treatment is fairly basic; however, there are many instances where diagnosis may not be as obvious as it appears. Confirmation with diagnostic testing is required. Performing endodontic diagnostic tests and recording findings are straightforward. Among endodontists, there can be disagreement regarding which tests are most helpful under which circumstances.4 This article will review endodontic diagnostic tests that are simple to perform, but may be challenging to interpret in some instances.

Endodontic disease is bacteria based, and while a mechanical component (eg, a fracture) may play a role, it is the introduction of bacteria or the byproduct of bacteria’s metabolic processes that initiates the endodontic disease process.5 Simply put, a pulp will not become inflamed or necrose unless bacteria are present. The pathways are well known: caries, fracture, trauma, and iatrogenics. Interestingly, periodontal diseases are not agents of endodontic disease. Treatment of periodontal diseases, however, can initiate endodontic disease by uncovering dentin tubules or severing neurovascular bundles at the apex or at orifices of accessory canals.6

PATIENT HISTORY AND CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Patients may present with a chief complaint of pain but endodontic disease may also be present in the absence of symptoms. When pain is present, the patient’s description of the pain is recorded:

- How long (hours, days, weeks, etc) has the pain been present?

- How strong is the pain (1 to 10 pain scale)?

- Is a stimulus required or is the pain spontaneous?

- Is the patient able to point out pain in an area of the mouth or a specific tooth?

This information constitutes the subjective findings of the examination. Any oral examination should be preceded by oral cancer screening. Signs of endodontic disease include presence of a sinus tract, swelling (location), dehiscence, extensive caries, recent restoration, failing/lost restoration, and tooth mobility.

After the initial clinical examination is completed, further tests are required to determine both the pulpal and periapical status. A meticulous review of radiographs should be performed, as always. Findings, such as extensive carious lesions, periapical radiolucent or radiopaque lesions, enlarged periodontal ligament spaces, thickened lamina dura, and vertical bone loss, may indicate active endodontic disease. It may be necessary to expose shift shots to verify the location of a lesion. The capture of periodic radiographs of previously endodontic-treated teeth is also recommended.

Reference teeth are used to determine a patient’s baseline response to stimulus. This is important, as responses to stimuli vary greatly—even on healthy teeth—from patient to patient. The most practical method is to isolate the quadrant or area of interest and test adjacent teeth that are disease- and symptom-free. There is no evidence to support the use of a contralateral tooth as a reference tooth.

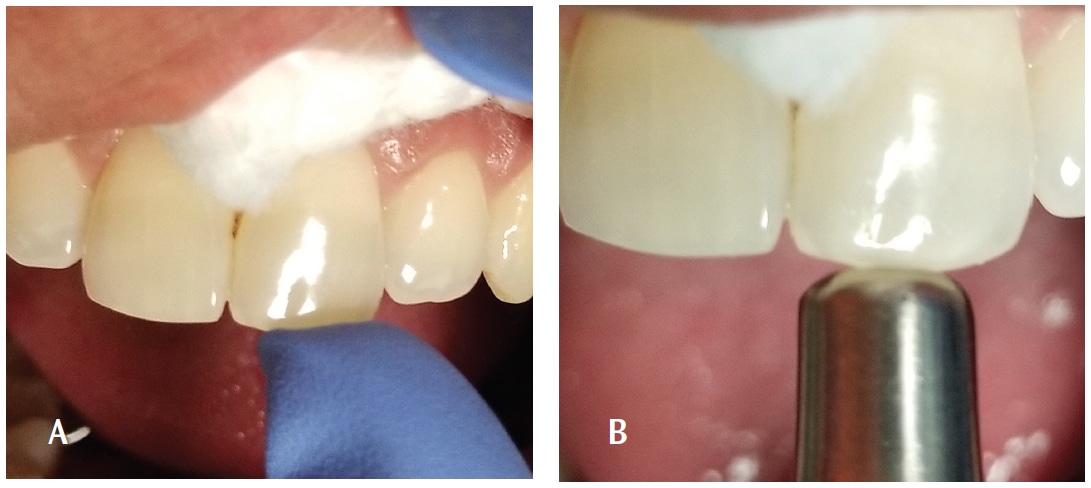

The percussion test is performed by tapping (lightly at first) on a tooth with a finger or the handle end of a mouth mirror (Figure 1). The patient can also be asked to tap on the tooth that is bothering him or her. If the pain is severe, there is no need to tap very hard. Percussion is an evaluation of inflammation in the attachment apparatus or cementum-periodontal ligament-cribriform plate complex. A painful response does not automatically mean that endodontic disease is present. A positive response to percussion may mean periapical tissues are affected (not infected) by pulpal inflammation or that a recently placed restoration is in hyperocclusion.

Palpation is performed by pressing along the alveolus and root eminences (Figure 2, page 35). Palpation is an evaluation for inflammation and/or swelling of the periosteum and underlying tissues. This type of sensitivity indicates that endodontic disease may be present and expanding beyond the confines of the medullary bone. Palpation should be performed on both the buccal and palatal aspects of the roots.

Periodontal probing, with appropriate recording of findings, is also an important component of endodontic diagnosis. An isolated area of deep probing could be indicative of a sinus tract draining through the periodontal ligament or it may be associated with a fracture. This type of information is essential in order to develop the appropriate treatment plan for the patient.

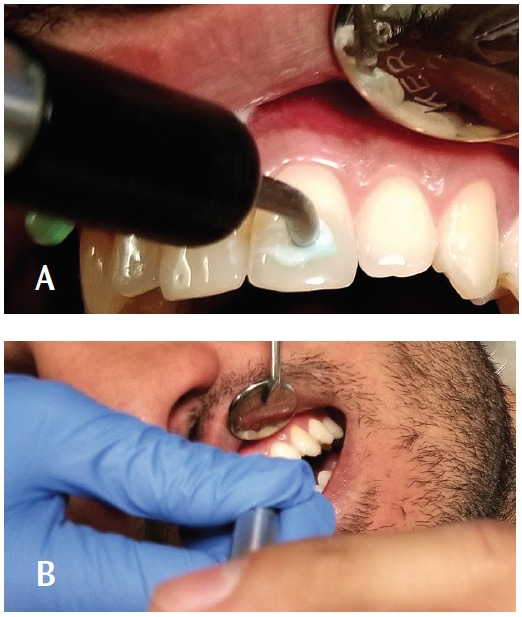

ELECTRIC TOOTH TESTERS

There are several different electric (or vitality) tooth testers available. Users should follow manufacturers’ directions. Basically, an electric pulp test requires the quadrant of interest to be isolated with cotton rolls and the teeth dried. Teeth should be dried with a 2×2 sponge and not air dried. Air drying can cause unnecessary pain for the patient with cold-sensitive teeth. Following, the probe (or wand) of the tester is placed on enamel or dentin using a contact media such as toothpaste. (Figure 3). The patient completes the “circuit” by touching the probe. An electric current is gradually increased until the patient feels a tingling or some sensation in the tooth.

The electric pulp test does not give a diagnosis. Also, there is no average or range of numbers associated with any group of teeth. As the electric pulp test is relative, the results suggest only “yes” or “no” for pulp vitality.7 False positives and false negatives can also occur, thus it is important to confirm with other diagnostic tests. If there is no response or an ambiguous response, the tooth should be retested by placing the probe on another surface of the tooth.

HOT AND COLD TECHNIQUES

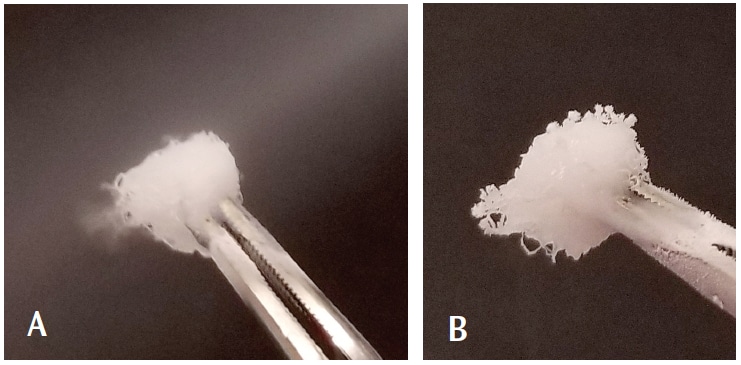

Teeth can be evaluated with cold or hot stimuli using any number of techniques. One easy method for cold testing is using a commonly available dental spray refrigerant containing 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane, which is more effective than ice or ethyl chloride.8The area or quadrant is isolated, as for the electric test, a cotton pellet is saturated with the spray (Figure 4), then touched to the tooth—not the gingivae—(Figure 5). The patient is asked to raise a hand or make a sound when (if) he or she feels “pain,” almost like biting into ice cream. If there is pain, the pellet is removed immediately and the patient is asked to indicate when the tooth feels “normal” again by putting his or her hand down. The intensity and duration of the pain should be recorded. Teeth are never sprayed directly.

Pain to cold is a response to movement of dentin tubular fluid stimulating neural endings of A-delta fibers. A response is considered “normal” if the pain stops as the stimulus (sprayed cotton pellet) is removed. However, if the pain lingers after removal of the stimulus, this is considered “abnormal.” A lingering response that begins to throb is also considered abnormal. Such a reaction suggests that neural C fibers are firing, and an irreversible inflammatory process is occurring.9 Additionally, an intense but brief response to cold may be normal, as demonstrated by a restoration or anesthesia lost during a restorative procedure. If there is no response or pain, pulp necrosis may be present.

A confusing aspect of thermal testing is that “no response” or no pain may be normal for that patient. This highlights the need for testing reference teeth and/or additional confirming tests. Always test at least two reference teeth in order to assess the patient’s normal response to cold. Some people with normal teeth almost jump out of the chair in response to cold, while others regularly chew ice.

Typical methods of heat testing include gutta-percha or compound material heated to melting temperature and directly applied to the tooth with lubricant in order to facilitate removal of the material (Figure 6). Use of heated endodontic obturation instruments, warm ball-ended metallic instruments, and hot water bathing with the tooth isolated by a rubber dam are alternative methods.

The heat test is a regularly discussed test among endodontic specialists. It is unusual, in that many people do not even feel heat on their normal teeth; however, it can be useful in the diagnosis of certain stages of endodontic disease. If the patient’s chief complaint is pain in response to coffee, soup, etc, the heat test may be most useful in isolating the tooth in question. However, there are many instances in which the heat test may provide no useful information. Again, this highlights the importance of gathering all information provided by the patient and from clinical test results prior to making a diagnosis.

While percussion is useful in isolating pain from inflamed periapical tissues, the bite test is more effective for determining sources of pain related to chewing, such as cracks or flexure of restorations overlying caries. Direct biting pressure in these areas can stimulate pulpal pain, rather than periapical discomfort. Many practitioners use cotton rolls or wooden bite sticks, but a band seater offers the means to more specifically determine the source of the pain. The band seater has two ends. The concave end is designed to be placed on a cusp tip and the patient then bites down and releases (Figure 7). The convex end is designed to be placed into the fossa (Figure 8). When testing lingual cusps, it is important to slightly angle the instrument so that the patient is not also putting pressure on the buccal cusp. The bite test does not help in diagnosing vertical root fracture.

CONCLUSION

This article provides a brief introduction and review of endodontic diagnosis and diagnostic technique for the dental hygienist. Whether a dental hygienist wants to include this in his or her armamentarium and knowledge base is up to the individual and the dentist. Collecting information regarding dental/endodontic pain is advantageous to patient flow, efficiency in office management, and, of course, patient care. There is much more in-depth information available to the reader. MEDLINE/PubMed searches for endodontic diagnosis and endodontic diagnostic technique will return a wealth of information.

REFERENCES

- Darby M, Margaret W. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2014.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation Accreditation. Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs. Available at: ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/dental_hygiene_standards.pdf?la=en. Accessed March 15, 2018.

- Abu-Tahun I, Rabah’ah A, Khraisat A. A review of the questions and needs in endodontic diagnosis. Odontostomatol Trop. 2012;35:11–20.

- Petersson K, Soderstrom C, Kiani-Anaraki M, Levy G. Evaluation of the ability of thermal and electrical tests to register pulp vitality. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1999;15:127–131.

- Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:340–349.

- Glickman GN. AAE Consensus Conference on Diagnostic Terminology: background and perspectives. J Endod. 2009;35:1619–1620.

- Pantera EA Jr, Anderson RW, Pantera CT. Reliability of electric pulp testing after pulpal testing with dichlorodifluoromethane. J Endod. 1993;19:312–314.

- Chen E, Abbott PV. Dental pulp testing: a review. Int J Dent. 2009;2009:365785.

- Pantera EA Jr. Nonsurgical treatment for endodontic emergencies. In: Hardin, ed. Clark’s Clinical Dentistry. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co; 1992.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2018;16(4):34-36,39.

Thanks for info!