Digital Revolution

How the implementation of electronic health records and telehealth is addressing the access-to-care problems faced in the United States.

This course was published in the November 2013 issue and expires November 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the benefits of using the Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry.

- Discuss the history of telehealth.

- Explain how telehealth works.

- List the advantages and challenges of using telehealth.

EHRs are becoming commonplace in dental practices. Their use facilitates communication and interdisciplinary collaboration, and they serve as the cornerstone of a new care delivery system—telehealth, which involves using technology to provide medical care from a distance.1 Teledentistry and telemedicine are terms used to describe the use of dental and medical technology to facilitate interaction between patients and health care providers in geographically different locations. These descriptions have been combined and are referred to collectively as “telehealth.”11 The federal government has recognized that the delivery of health care using telehealth technologies is a cost-effective alternative to traditional in-person medical care.1 Telehealth seeks to improve health by permitting two-way, real-time interactive communication between patients and physicians/ practitioners at a distant site.1 In order for telehealth to succeed, hospitals, dental practices, and medical offices need to convert paper patient records to multifunctional EHRs that include patients’ medical and dental histories.

ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS

To be considered multifunctional, EHRs need to have at least two of the following: a list of all patients’ medications; a list of patients due for preventive care; electronic prescribing capabilities; and medical alerts about potential drug interactions.2 The pace of EHR adoption in the US has been accelerating since the passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act in 2009, which has made funds available to hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers for the adoption and “meaningful use” of this technology through 2021.2

In 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act into law, which has aided in the expansion of broadband and wireless service, and established financial incentives for Medicare and Medicaid providers to adopt EHR technology by 2015.3 Additional requirements under the federal EHR incentive program include the purchase and meaningful use of EHR technology that has been certified according to standards established by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Although the meaningful-use provision is complex, it basically requires health care providers to demonstrate they are using certified EHR systems in a significant way that allows more effective patient care through the electronic sharing of health records with the patient and all members of the health care team.

Beyond the federal EHR meaningful use incentive program, there is additional financial motivation for practices that treat Medicare patients to adopt EHRs, as clinicians who bill Medicare for services will see their reimbursement rates reduced if they fail to effectively implement certified EHR technology by 2015.4

To help dental providers make the change to EHRs, the American Dental Association created a task force in 2007 that designed an online database system called Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry (SNODENT®).3,5 This is an internationally recognized system of vocabulary and codes designed specifically for use with EHRs. Its purpose is to: provide standardized terms for describing dental disease; capture clinical dental and patient characteristics; permit analysis of patient care services and outcomes; and to be interoperable with EHRs.5 The benefits of using SNODENT include: improved communication among dentists and other health care providers; improved patient care through evidence-based practices; enhanced data collection to evaluate oral care outcomes; enhancement of public health investigation and reporting; and greater capability to measure adherence to standards of care.5 The use of SNODENT as the standard for EHRs will prepare oral health professionals for treating patients who seek dental treatment across state lines.

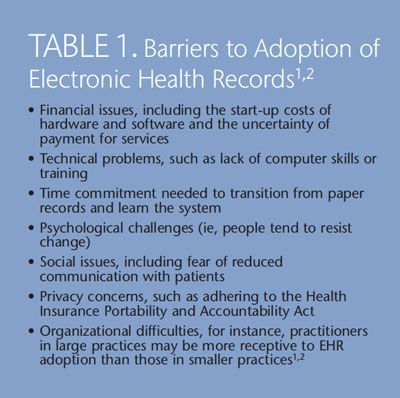

While the establishment of EHR systems should help streamline the business side of the dental practice, there are barriers to adoption of this technology (Table 1).1,2 Dental practices, especially those that accept Medicare or Medicaid patients, should begin preparing for the impending nationwide adoption of EHRs.

NATIONAL SYSTEM FOR ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS

A national system of EHRs is necessary so that the health histories of patients who need medical or dental treatment outside of their home state are available to new providers. After Hurricane Katrina—one of the deadliest hurricanes ever to hit the US—several states partnered to ensure their residents’ health information was readily available in case of future disasters. Working with the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, health information exchange (HIE) programs were implemented in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Michigan, Wisconsin, and West Virginia. The programs enable the exchange of health information among providers caring for patients who are displaced from their homes by natural disaster.6

Patients benefit from these exchanges, in which state and HIE organizations join forces to ensure that health information is available, as it guarantees access to their health records when it is needed most. The Southeast Regional Health Information Technology and Health Information Exchange Collaboration (SEARCH) was established in 2010, with the goal of resolving cross-border barriers to the multistate exchange of health information.6

Collaboration between SEARCH’s member states—Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia—resulted in an agreement to exchange health information, including electronic medical and dental records, for patients who are displaced by natural disasters.

TYPES OF DENTAL ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS

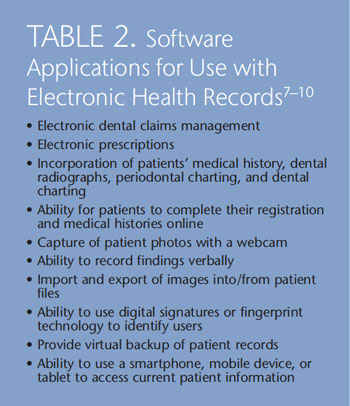

Several EHR software programs are designed specifically for dental offices. These programs allow for more efficient communication and provide a reduction in the paper trail generated between providers, specialists, and rural telehealth sites.3 Table 2 lists the applications for these software programs.7–10

When choosing software, both components of the federal incentives to implement EHRs (ie, reimbursements for the purchase and meaningful use of EHRs, and Medicare compensation rates) require the use of federally certified EHR software. Beyond this, dental offices will want to consider how user-friendly the system is; the cost of software installation, staff education, and tech support; customization capabilities for dental documents; and EHR security and confidentiality. The variation in the level of acceptance and use of dental EHRs throughout the profession is affected by clinicians’ preferred mode of communication, type of software and hardware used, and the strength and availability of an internet connection.

HISTORY OF TELEDENTISTRY

The roots of telemedicine can be traced to 1924, when the concept of physicians using radios and early television monitor technology to “see” patients was suggested.11 The initial concept of teledentistry was part of the blueprint for dental informatics, which was drafted at a 1989 conference funded by the Westinghouse Electronics Systems Group in Baltimore.12 The birthplace of teledentistry as a subspecialist field of telemedicine can be linked to a 1994 project of the US Army Total Dental Access Project, which aimed to improve patient care, dental education, and communication between dentists and dental laboratories.3,11,12,13 Teledentistry was used by the Army to provide medical consultation to people more than

100 miles away.11 Since this time, public health facilities, remote rural clinics, and other organizations have implemented teledentistry with varying degrees of success.

METHODS OF COMMUNICATION

Consultation through telehealth takes place with “real-time,” “store-and-forward,” or “remote monitoring” communication methods. 3,11–13 Real-time consultation is a videoconference in which dental professionals see, hear, and communicate with patients using advanced telecommunication technology and ultra-high bandwidth network communications (Figure 1).11–13 Store-and-forward communication is the collection and secure transmission of encoded patient information, including documents and images (intraoral photos, radiographs, and extraoral photos), that is stored for review by a dentist or specialist prior to future consultation and treatment planning.3,11–13

These data can then be shared among multiple providers.12 A third method, remote monitoring, involves the distant monitoring of hospitalized or home-based patients.12 Regardless of a clinician’s preferred method of teleconsultation, data sharing is vital to patients who need the advice of a specialist, but who may not have one nearby. Telehealth also benefits patients who have been displaced by natural disasters or who require constant monitoring.

TECHNOLOGICAL REQUIREMENTS

Practicing dentistry within the realm of telehealth requires clinicians to be equipped with a desktop or laptop computer that includes a microphone, substantial hard drive and random-access memory, and a speedy processor. A digital camera, video camera, intraoral camera, and portable X-ray unit are also needed.11,12 A comprehensive software program capable of image acquisition and storage, transmission of the gathered information, and the ability to code and decode audio and video is desirable.11 A fax machine, scanner, and printer may also be necessary.12 Quick, reliable connection to the internet is essential to telehealth professionals and their staff when delivering care.11

ADVANTAGES

Telehealth provides a unique way to overcome the barriers of geography to deliver patient care, as well as hands-on training and continuing education to oral health professionals in remote clinics.11,14 Its application is of great value in underserved areas, both rural and urban, where there is a dearth of available specialists. Institutions, such as nursing homes, are also ideal sites for telehealth, as residents may have difficulty accessing off-site health care providers.

Telehealth can reduce the cost of service and improve quality of care.12,13,15 For example, the screening of young children for caries is expensive and requires significant labor. Kopycyka-Kedzierawksi and Billings16 examined the efficacy of using telehealth examinations vs in-person visual examination to identify patients at high-caries risk. The cohort of 291 subjects was divided into two groups: one received telehealth examinations while the other received in-person examinations. Both groups returned for a face-to-face follow-up at 6 months and 12 months after the initial examination. The researchers found that the results of the telehealth examinations were comparable to in-person examinations when screening for caries among young children.16

Employing telehealth increases interprofessional communication, which may improve dentistry’s integration into the larger health care delivery system.13 Second opinions, preauthorizations, and other insurance requirements can be met almost instantaneously online, and the use of real-time images makes traditional dental care more efficient.14,15 In addition, telehealth can facilitate greater use of nondentist providers (dental hygienists or midlevel providers), and improve early diagnosis and treatment outcomes of oral disease.14

Within dental and dental hygiene schools, interactive video-conferencing allows for the evaluation of patient information (with or without the patient being present), and promotes purposeful interaction between educators and students.15 In addition, telehealth may also allow oral health professionals to evaluate and meet the oral health needs of children at school and childcare centers.15

CHALLENGES

Though telehealth is used on a global scale by educational institutions and public health facilities, many concerns—legal, financial, and ethical—remain. Telehealth enables dental hygienists to initiate treatments based on their assessment of patient needs, without the consent or supervision of an on-site dentist. However, these supervision levels vary by state, affecting the level of service and care a dental hygienist can deliver in rural and remote settings using teledentistry equipment.3 Accountability, licensure, jurisdiction, liability, privacy, informed consent, and malpractice are crucial points to consider when attempting to establish a telehealth practice.11,13

The most significant barrier to nationwide implementation of teledentistry is the traditional system of state-by-state licensure. There is no law to clarify the role of the telepractitioner and his or her liability.11 The cost of the telecommunication equipment is also daunting. To date, virtual teledental consultations are not reimbursable by insurance companies.3,12

Ethically, patients need to understand that their medical and dental information will be transmitted electronically, and the possibility exists that the information will be intercepted—despite best efforts to maintain security and confidentiality.11,13 Other challenges include: the time it takes for practitioners and staff to get acclimated to using the telehealth system; lack of infrastructure; and low patient literacy.

TELEDENTISTRY AT WORK

Several states are at the forefront of telehealth technology, including Alaska, Minnesota, and California. According to Mary Williard, DDS, director of the Alaska Dental Health Aide Therapist (DHAT) training program, DHATs and nearly all health care providers in Alaska’s Tribal Health System use telehealth technology provided by the Alaska Federal Health Care Access Network (AFHCAN). Williard explains that AFHCAN, a nonprofit organization run by the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, enabled all village clinics to adopt telehealth carts.

Apple Tree Dental in Minnesota is a nonprofit dental practice that operates five regional dental access programs in urban and rural areas of Minnesota.1 Telehealth technologies link special care dental professionals with on-site dental clinics at schools, Head Start Centers, group homes, assisted-living centers, nursing facilities, and other community sites for people facing physical, financial, and geographical barriers to care.1 The Apple Tree model links dental hygienists working under collaborative agreements with dentists.1 The practice has found that approximately 70% of the children treated in Head Start Centers need only preventive services provided by the dental hygienist.1 A dentist treats the other 30% who require additional care during onsite visits with portable equipment.1

The Pacific Center for Special Care at the University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco created a “Virtual Dental Home”—complete with a collapsible dental chair, laptop computer, digital camera, supplies to do temporary fillings, an internet-based dental record system, and a handheld X-ray machine where registered dental hygienists in alternative practice (RDHAP), registered dental hygienists working in public health programs, and registered dental assistants provide care to underserved populations in schools, nursing homes, community centers, and Head Start centers.17–20 These teams, led by geographically distant dentists, provide triage, case management, preventive procedures, and early intervention therapeutic services.17

Telehealth technology allows for the medical histories and dental images to be uploaded to a website where a dentist reviews them and creates a treatment plan or refers patients requiring more complex treatment to a dentist in their area.20

CONCLUSION

The use of telehealth has not yet been adopted into mainstream delivery of oral health care. Its implementation into dentistry, however, is necessary to improve the health of at-risk populations. The use of telehealth by dental hygienists and midlevel providers in nontraditional settings can make a difference in the fight to improve access to care among underserved populations. Dental and dental hygiene schools can also benefit from the use of telehealth technology through improvements in interdisciplinary and interprofessional learning.

The benefits of implementing EHRs—combined with the technology to facilitate dental care at remote sites—have set the stage for the adoption of telehealth clinics nationally and internationally. Several issues must be addressed, however, before telehealth becomes widespread. The future of telehealth is dependent on federal grants to continue program development in dental and dental hygiene schools, public health facilities, and other organizations; the use of reimbursable codes by dental professional for the use of technology and virtual visits; and widespread acceptance of the use of dental hygienists and midlevel providers in nontraditional settings.

REFERENCES

- Glassman P, Helgeson M, Kanteles J. Usingtelehealth technologies to improve oral healthfor vulnerable and underserved populations.J Calif Dent Assoc. 2012;40:579–585.

- Kaiser Permanente International. Adoption ofElectronic Health Records in the United States.Available at: xnet.kp.org/kpinternational/docs/Adoption%20of%20Electronic%20Health%20Records%20in%20the%20United%20States.pdf.Accessed October 9, 2013.

- Williams KT. The use of teledentistry toprovide dental hygiene care to rural populations.Access. 2011;25:1–6.

- American Dental Association. ElectronicHealth Records Frequently Asked Questions.Available at: www.ada.org/sections/dentalPracticeHub/ members/ehr_faqs.pdf.Accessed October 9, 2013.

- American Dental Association. SystemizedNomenclature Of Dentistry (SNODENT).Available at: www.ada.org/snodent.aspx.Accessed October 9, 2013.

- United States Department of Health andHuman Services. States Prepare for SeamlessExchange of Health Records. Available at: www.hhs. gov/ news/press/ 2013pres/07/20130711a.html. Accessed October 9, 2013.

- Patterson/Eaglesoft. Eaglesoft software benefitsand features. Available at: patterson.eaglesoft.net/ PracticeManagementCharting/Overview. Accessed October 9, 2013.

- Carestream Dental/CS PracticeWorks. CSPracticeWorks Software Features. Available at:www.carestreamdental.com/us/en/practicemanagement/PRACTICEWORKS#Features and BenefitsAccessed October 9, 2013.

- HenrySchein/Dentrix. Dentrix PracticeManagement Software Features. Available at:www.dentrix.com/products/dentrix/digital-dentaloffice.Accessed October 9, 2013.

- Mogo. Mogo Dental Software Features.Available at: www.mogo.com/ operatory. shtml.Accessed October 9, 2013.

- Sanjeev M, Shushant GK. Teledentistry a newtrend in oral health. International Journal ofClinical Cases and Investigations. 2011;2(6):49–53.

- Jampani ND, Nutalapati R, Dontula BSK,Boyapati R. Applications of teledentistry: aliterature review and update. Journal ofInternational Society of Preventive andCommunity Dentistry. 2011;1(2):37–44.

- Bhambal A, Saxena S, Balsaraf SV.Teledentistry: potentials unexplored. Journal ofInternational Oral Health. 2010;2(3):1–6.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra A, Jain R, Kaur H, BansalS. Role of teledentistry in dental education: needof the era. J Clin Diagn Res. 2011;5:1486–1488.

- Skillman SM, Doescher MP, Mouradian WE,Brunson DK. The challenge to delivering oralhealth services in rural America. J Pub HealthDent. 2010;70(Suppl 1):S49–S57.

- Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Billings RJ.Comparative effectiveness study to assess twoexamination modalities used to detect dentalcaries in preschool urban children. Telemed J EHealth. 2013 Sep 21. Epub ahead of print.

- Glassman P, Harrington M, Namakian M,Subar P. The virtual dental home: bringing oralhealth to vulnerable and underserved popu -lations. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2012;40:569–577.

- Telehealth Project Brings Virtual DentalHome To Patients. California Healthline.Available at: www.californiahealthline.org/insight/2013/telehealth-project-bringsvirtual-dental-home-to-patients. AccessedOctober 9, 2013.

- Pacific Insider: University of the Pacific.Dental School Pilots Telehealth Project in SanMateo County. Available at: www.pacific.edu/About- Pacific/ Newsroom/2013/May—August-2013/ Dental-School-Pilots-Telehealth-Project-in-San-Mateo-County.html. AccessedOctober 9, 2013.

- California Health Report. Virtual DentalHomes Care For Vulnerable Populations.Available at: www.healthycal.org/archives/10842.Accessed October 9, 2013.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2013;11(11):50–54.