SKYNESHER/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

SKYNESHER/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Diagnostic Tips for Benign White Oral Mucosal Lesions

Differentiating between benign and malignant white mucosal lesions is challenging.

PART 1 of a two-part series The first article in this two-part series explores benign white oral mucosal lesions encountered in dental practice. Appearing in a future issue, Part 2 will focus on malignant and premalignant white lesions.

This course was published in the October 2020 issue and expires October 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe etiologic pathways and presenting characteristics of white mucosal lesions encountered in dental practice.

- Discuss risk factors for white mucosal lesions, and approaches to clinical assessment and diagnosis.

- Explain strategies for managing benign white lesions.

All oral healthcare professionals encounter patients with white oral mucosal lesions, a presentation that raises the challenge of distinguishing lesions that are harmless from those that represent potentially malignant disorders. Recognition of the key clinical features of these lesions is an important aspect of daily practice, with general dentists and dental hygienists leading the way in providing thorough examinations for new patients, as well as existing patients during routine recare appointments. White oral mucosal lesions often result from an increase in the thickness of the surface keratin layer that may develop from a variety of etiologic pathways, including—but not limited to—traumatic, inflammatory, and neoplastic. Part 1 of this article will focus on white oral mucosal lesions that are benign in nature; appearing in a future issue, Part 2 will address malignant and premalignant lesions.

REACTIVE LESIONS

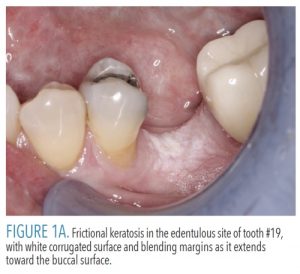

Frictional keratosis represents increased keratin production in response to chronic mechanical irritation. The retromolar pad and edentulous alveolar ridge are the most common sites of involvement due to trauma from food being crushed against the mucosa during mastication.1 A fractured tooth or rough restoration may lead to the development of frictional keratosis on the adjacent lateral tongue or buccal mucosa. Frictional keratosis appears as a discrete white plaque with a rough or corrugated surface and frequently has blending margins with the adjacent unaffected mucosa (Figure 1A). These lesions do not undergo malignant change and should resolve after the source of irritation is eliminated.2–4 Because frictional keratosis is a specific entity, it should not be described or categorized as a leukoplakia. Including frictional keratosis in studies of leukoplakia dilutes the prevalence of dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma seen in true leukoplakia, a potentially malignant disorder.1

Morsicatio. Whereas frictional keratosis occurs during normal function, morsicatio is the term used for habitual chewing of the mucosal surfaces. While some patients are consciously aware of their habit, others are not. Morsicatio only occurs in areas easily traumatized by the teeth; these include buccal mucosa (morsicatio buccarum), lower lip (morsicatio labiorum), or lateral tongue (morsicatio linguarum).3,5 The lesions appear as shaggy, macerated white plaques, with keratin tags (Figure 1B). The involved areas blend gradually into surrounding normal mucosa and the clinical findings are usually diagnostic. No treatment is necessary for morsicatio, as there are no associated negative consequences.4

Smokeless tobacco keratosis (snuff dipper’s lesion). The use of smokeless tobacco products (eg, moist snuff, dry snuff, or chewing tobacco) can cause characteristic mucosal changes at the site of product placement, most often the lower labial or buccal vestibule. Approximately 2% to 3% of Americans age 12 and older reportedly use smokeless tobacco products.4 These lesions present as asymptomatic, wrinkled, or corrugated grayish-white plaques exhibiting margins that blend with the adjacent normal mucosa (Figure 2). Following discontinuation of smokeless tobacco use, lesions should resolve within approximately 6 weeks.5 Should lesional tissue persist or if atypical features are present initially, biopsy of the area is recommended to evaluate for possible neoplastic changes. Patients who use smokeless tobacco have an increased risk of developing oral cancer, however, the relative risk is lower than those who smoke tobacco.

Smokeless tobacco keratosis (snuff dipper’s lesion). The use of smokeless tobacco products (eg, moist snuff, dry snuff, or chewing tobacco) can cause characteristic mucosal changes at the site of product placement, most often the lower labial or buccal vestibule. Approximately 2% to 3% of Americans age 12 and older reportedly use smokeless tobacco products.4 These lesions present as asymptomatic, wrinkled, or corrugated grayish-white plaques exhibiting margins that blend with the adjacent normal mucosa (Figure 2). Following discontinuation of smokeless tobacco use, lesions should resolve within approximately 6 weeks.5 Should lesional tissue persist or if atypical features are present initially, biopsy of the area is recommended to evaluate for possible neoplastic changes. Patients who use smokeless tobacco have an increased risk of developing oral cancer, however, the relative risk is lower than those who smoke tobacco.

INFECTIOUS LESIONS

Candidiasis is a common superficial fungal infection caused by Candida species. Most cases are due to C. albicans, which has been identified as commensal in 30% to 60% of the adult population.3,6 Immunosuppression is a strong risk factor for oral candidiasis, however, the condition is not uncommon in healthy patients when the normal flora is altered. Anemia and diabetes mellitus are other known systemic predispositions.7 Local oral environmental factors, such as xerostomia, recent antibiotic therapy, and wearing acrylic appliances, can contribute to the development of candidiasis.

Oral candidiasis has multiple clinical presentations, some of which are not white in appearance and therefore not discussed, including angular cheilitis (cracking at the commissures) and erythematous candidiasis (atrophy and redness, common on the dorsal tongue). Azole antifungal medications are effective for most cases of candidiasis. While systemic fluconazole offers easy, infrequent dosing, it interacts with many medications, including anticoagulants, phenytoin, oral hypoglycemics, and statins.4,8 Clotrimazole troches are not considered systemic due to their poor absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, but compliance can be difficult since they must be dissolved intraorally five times daily. Nystatin suspension is a polyene antifungal that also requires five doses per day. Practitioners should keep in mind that dentures or other oral appliances must be treated in patients who have candidiasis. Dentures are frequently colonized by Candida species, even in the absence of denture stomatitis or other clinical signs of candidiasis.9 Acrylic dentures can be disinfected by soaking overnight in bleach diluted with water at a 1:10 ratio.8 Appliances containing any metal or soft liner may be soaked in nystatin suspension.

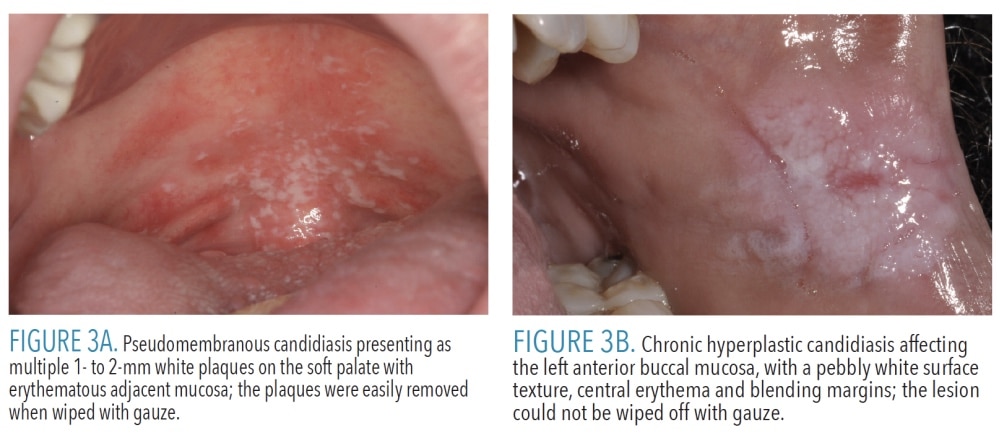

Pseudomembranous candidiasis, also called thrush, is characteristically seen in newborns, immunocompromised patients, and patients who use steroid inhalers for asthma.6 Multiple creamy white plaques consisting of desquamated epithelial cells and fungal organisms may be seen on any mucosal surface (Figure 3A). Pseudomembranous candidiasis is the only white lesion discussed here that can be wiped off. The mucosa underlying the plaques is often erythematous, but should be intact.4 Patients may be completely asymptomatic, or report a mild burning sensation or foul taste.Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis is an uncommon form of candidiasis that presents as a leukoplakia, most often on the lateral tongue or buccal mucosa6 (Figure 3B). Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis often has a mixed appearance, with intervening areas of erythema.4 This diagnosis can be challenging because candidal organisms may be superimposed on many keratotic lesions. By definition, chronic hyperplastic candidiasis should resolve completely with antifungal therapy.6 Should lesional tissue persist, biopsy is indicated to evaluate for the possibility of epithelial dysplasia.

![]() IMMUNE-MEDIATED LESIONS

IMMUNE-MEDIATED LESIONS

Erythema migrans (geographic tongue, benign migratory glossitis) is a common, harmless condition present in up to 2% of the population.2 It is believed to be immune-mediated and frequently occurs in conjunction with fissured tongue.10 Lesions of erythema migrans present as smooth, atrophic red patches surrounded at least partially by thin, serpentine white borders (Figure 4). Erythema migrans has a migrating, waxing, and waning pattern, and gets its alternate name (geographic tongue) from the resemblance of continents on the globe.10 The dorsal and lateral tongue are most often involved, but the ventral tongue can be affected. Lesions can also occur on almost any other mucosal surface. Erythema migrans is usually clinically diagnostic, however, cases occasionally undergo biopsy and, microscopically, may appear similar to psoriasis. Compared to the general population, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that patients with psoriasis are three times more likely to have erythema migrans.11

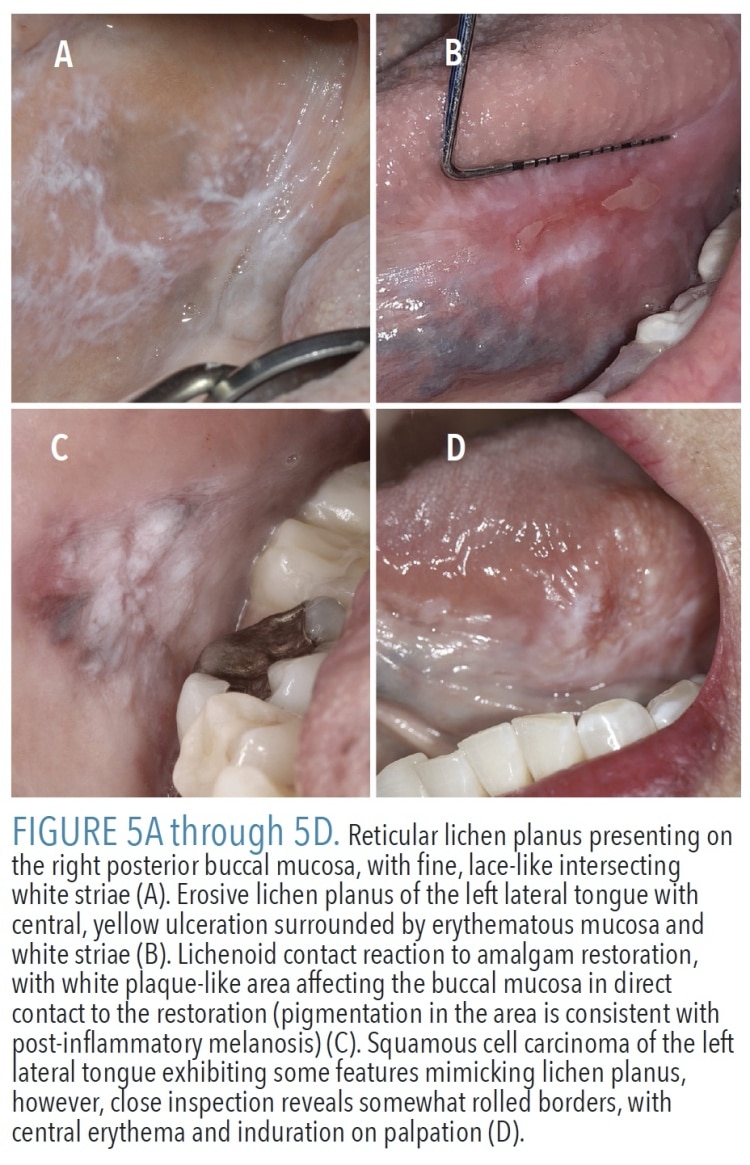

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is an immune-mediated condition that may affect the skin and/or mucosa with no clear etiology. It affects up to 2.2% of the population worldwide, most often in patients ages 30 to 80.12 By a 3:2 ratio, women are affected slightly more often than men.4 It presents as multiple lesions that most often occur on the buccal mucosa, followed by the gingiva, tongue, and labial mucosa.2 Lesions are bilateral and have a relatively symmetrical distribution. Although six clinical patterns of OLP are recognized, this discussion will focus on the two most common forms: reticular and erosive. Reticular OLP is characterized by lace-like intersecting white lines (striae) without erosions or ulceration (Figure 5A). When OLP affects the dorsal tongue, a more plaque-like appearance may be seen (rather than the characteristic striae).3 Erosive OLP typically presents as erosions and ulcers, with surrounding or intervening striae (Figure 5B). Occasionally, erosive OLP is limited to the gingiva and may present solely as desquamative gingivitis.

Diagnosis can be challenging due to multiple other known clinical and microscopic mimics of OLP, including lichenoid contact reaction and drug-induced lichenoid reaction (DILR). Lichenoid contact reaction is limited to the mucosa in direct contact with the offending agent, usually a dental material, and thus is most often seen on the buccal mucosa (Figure 5C) or lateral tongue.3 A long and growing list of medications is implicated in the development of DILR, which is often unilateral.3 The multifocal and bilateral nature of OLP help distinguish it from lichenoid contact reaction and DILR, but other conditions, including mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, chronic ulcerative stomatitis, lupus erythematosus, and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia, can all have a diffuse presentation similar to OLP. In many cases, a biopsy is required and diagnosis should be based on the combination of clinical and histopathologic features.12

Diagnosis can be challenging due to multiple other known clinical and microscopic mimics of OLP, including lichenoid contact reaction and drug-induced lichenoid reaction (DILR). Lichenoid contact reaction is limited to the mucosa in direct contact with the offending agent, usually a dental material, and thus is most often seen on the buccal mucosa (Figure 5C) or lateral tongue.3 A long and growing list of medications is implicated in the development of DILR, which is often unilateral.3 The multifocal and bilateral nature of OLP help distinguish it from lichenoid contact reaction and DILR, but other conditions, including mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, chronic ulcerative stomatitis, lupus erythematosus, and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia, can all have a diffuse presentation similar to OLP. In many cases, a biopsy is required and diagnosis should be based on the combination of clinical and histopathologic features.12

The World Health Organization classifies OLP as a premalignant condition; however, this designation is controversial for multiple reasons. Vital clinical information and/or biopsy evidence is lacking in many early case reports of OLP transforming to squamous cell carcinoma. Additionally, there can be substantial overlap between OLP and premalignant lesions, which was illustrated by a study that found microscopic features of OLP in 29% of epithelial dysplasias and squamous cell carcinomas.13 This suggests some cases of alleged malignant transformation of OLP were, in fact, premalignant lesions having a deceptively lichenoid appearance (Figure 5D). Two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of OLP studies found an average malignant transformation rate of 1.09% to 1.4%, with the tongue being the most common location.14,15 Whether OLP is an independent risk factor for malignant transformation is difficult to ascertain given that confounding factors, such as tobacco use, were not recorded in some studies.16

Patients with OLP should be reassessed at least annually. Reticular OLP requires no treatment due to its asymptomatic nature. The goal of therapy in patients with erosive OLP is not curative; rather, it is to manage the inflammation and associated discomfort, especially when eating and drinking.7,12 Treatment involves topical corticosteroids, such as 0.05% fluocinonide, betamethasone, or clobetasol gel.8 Clinicians are advised to prescribe gel formulations because creams and ointments do not adhere to the oral mucosa. Liquid corticosteroid suspensions (swish and expectorate) can be used for cases with extensive involvement. Iatrogenic candidiasis is a common problem that contributes significantly to symptoms, therefore, periodic antifungal treatment is often necessary for these patients.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals play a critical role in detection and diagnosis of oral mucosal lesions, followed by appropriate treatment or referral to a specialist when indicated. Differentiating white mucosal lesions that are most likely benign from those that are clinically suspicious for dysplasia or malignancy can challenge even the most experienced clinicians. If not readily diagnostic upon clinical examination, biopsy for white lesions—even those thought to be benign—is in the best interest of the patient in order to reach a definitive diagnosis.

References

- Natarajan E, Woo SB. Benign alveolar ridge keratosis (oral lichen simplex chronicus): A distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:151–157.

- Jones KB, Jordan R. White lesions in the oral cavity: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2015;34:161–170.

- Mortazavi H, Safi Y, Baharvand M, Jafari S, Anbari F, Rahmani S. Oral white lesions: An updated clinical diagnostic decision tree. Dent J (Basel). 2019;7:10.3390/dj7010015.

- Neville B, Damm D, Allen C, Chi A. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier; 2016.

- Muller S. Frictional keratosis, contact keratosis and smokeless tobacco keratosis: Features of reactive white lesions of the oral mucosa. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:16–24.

- Hellstein JW, Marek CL. Candidiasis: Red and white manifestations in the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:25–32.

- Warnakulasuriya S. White, red, and mixed lesions of oral mucosa: A clinicopathologic approach to diagnosis. Periodontol 2000. 2019;80:89–104.

- Villa A, Woo SB. Leukoplakia — A diagnostic and management algorithm. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75:723–734.

- Gacon I, Loster JE, Wieczorek A. Relationship between oral hygiene and fungal growth in patients: Users of an acrylic denture without signs of inflammatory process. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1297–1302.

- McNamara KK, Kalmar JR. Erythematous and vascular oral mucosal lesions: A clinicopathologic review of red entities. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:4–15.

- Gonzalez-Alvarez L, Garcia-Martin JM, Garcia-Pola MJ. Association between geographic tongue and psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analyses. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48:365–372.

- Cheng YS, Gould A, Kurago Z, Fantasia J, Muller S. Diagnosis of oral lichen planus: A position paper of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:332–354.

- Fitzpatrick SG, Honda KS, Sattar A, Hirsch SA. Histologic lichenoid features in oral dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117:511–520.

- Fitzpatrick SG, Hirsch SA, Gordon SC. The malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: A systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:45–56.

- Iocca O, Sollecito TP, Alawi F, et al. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral cavity and oral dysplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of malignant transformation rate by subtype. Head Neck. December 5, 2019. Epub ahead of print.

- Muller S. Oral lichenoid lesions: Distinguishing the benign from the deadly. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(Supp 1):S54–S67.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2020;18(9):40-43