Diabetes in the Dental Office

Oral health professionals should have a basic understanding of glycemic monitoring and management to best serve patients with this common chronic disease.

This course was published in the May 2015 issue and expires May 31, 2018. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the two main types of diabetes.

- Discuss the value of laboratory testing and patient self-glucose monitoring.

- Explain how the HbA1c test can be used by oral health professionals to manage patients with diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease affecting more than 29 million Americans, or approximately 9% of the United States population.1,2 About one-third of those with the disease remain undiagnosed, which means they are not adequately maintaining their health. With such a high prevalence, oral health professionals will likely encounter patients with diabetes in their practices.

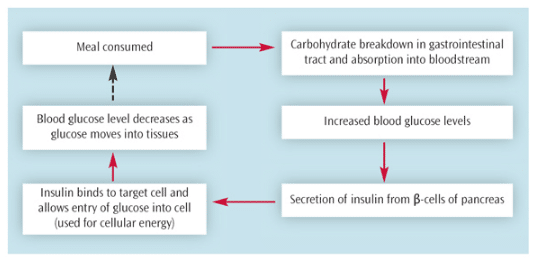

In order to understand diabetes, the dental team must learn how carbohydrates are metabolized (Figure 1).3,4 In an individual without diabetes, eating a meal initiates a series of events that results in the breakdown of complex carbohydrates into simple sugars (glucose), which are then absorbed across the gastrointestinal lining into the bloodstream. As the blood glucose levels rise, insulin is secreted from the pancreatic ?-cells. Glucose is too large a molecule to pass across the cell membrane of target cells—such as muscle cells, which are major consumers of glucose—without the action of insulin. Insulin binds to receptors on target cells, increasing permeability to glucose and allowing glucose to enter the target cells (Figure 2). Blood glucose levels decrease as glucose is absorbed into muscle cells.

There are two main types of diabetes: type 1 (formerly referred to as insulin-dependent diabetes) and type 2 (formerly referred to as noninsulin-dependent diabetes).4,5 Patients with type 1 diabetes lack the ability to produce insulin. Insulin production diminishes and eventually ceases when a patient’s autoimmune system destroys the pancreatic ?-cells. These patients rely on insulin injections to maintain normal blood glucose levels. Patients with type 1 diabetes are generally diagnosed in childhood or young adulthood.

Type 2 constitutes 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases and is more common in nonwhite populations. Its main cause is insulin resistance.3–5 Patients with type 2 diabetes can produce insulin, but their muscle cells exhibit insulin resistance. After a meal, the pancreas secretes insulin, but the insulin does not effectively activate its receptor on target cells, so glucose transport into the cells is inhibited. These patients do not rely on insulin injections for survival, but they may take medications that alter insulin production by the pancreas and insulin sensitivity at the target cells.6 Patients with type 2 diabetes may also take supplementary insulin as part of their management regimen. Insulin resistance may be reduced by weight loss and pharmacotherapy but is generally never restored to normal.

Diabetes and periodontal diseases are closely associated via a two-way relationship, in which poor glycemic control affects the periodontium and periodontal diseases are associated with negative effects on glycemic control.2,7 Diabetes is a risk factor for periodontitis, even among young people.8,9 Current research also indicates that periodontitis may be an important factor in glycemic control.2 As such, it is imperative that patients with diabetes maintain their oral health and glycemic control. Communication and cooperation between medical and dental health care providers is key to supporting the health of individuals with diabetes.

LABORATORY TESTING AND SELF-GLUCOSE MANAGEMENT

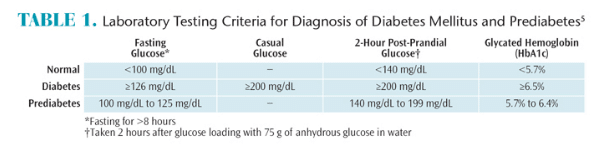

Diabetes is diagnosed by a physician using different types of blood glucose testing (Table 1).5,10 Fasting blood glucose, casual blood glucose, and post-prandial plasma glucose tests are used to evaluate blood glucose levels at a single point in time. These tests can evaluate only the blood glucose level at the exact moment the blood is drawn. In the bloodstream, glucose binds to numerous proteins, and the higher the blood glucose levels, the higher the percentage of total protein that becomes glycated. As glucose circulates in the bloodstream, it attaches irreversibly to part of the oxygen-carrying hemoglobin molecule on red blood cells.

The irreversible binding of glucose to hemoglobin is the basis of the HbA1c test. Glucose remains bound to the hemoglobin molecule for the entire lifespan of the red blood cell, which is approximately 120 days.11 High HbA1c levels indicate that a greater percentage of the hemoglobin on red blood cells has become glycated by the circulating blood glucose. Unlike the fasting, casual, and post-prandial glucose tests that measure the glucose content of blood at any given moment, the HbA1c test provides the approximate glucose level in the bloodstream over the 2 months to 3 months prior to the lab test being performed.11

The HbA1c lab test can be used in both the diagnosis of diabetes and the evaluation of long-term glycemic control.5 When used for diagnosis, an HbA1c value of less than 5.7% is considered normal. An HbA1c of ?6.5% is diagnostic for diabetes, while an HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4% is used to diagnose prediabetes.5

For patients diagnosed with diabetes, the quality of glycemic control is directly related to the risk of developing complications, such as kidney, eye, and nerve disease.12,13 Therefore, physicians use diet, exercise, and medications to maintain glycemic control in their patients that is as close to normal as possible. The American Diabetes Association recommends people with diabetes control their blood sugar so that the HbA1c level remains <7%.5 In the US diabetes population, only about 30% of patients are able to attain this target range.14 When a patient’s HbA1c rises above 8%, the American Diabetes Association recommends the physician intervene with changes in the diabetes management regimen.5

Just as a physician does not use a patient’s single blood pressure reading to evaluate hypertension, a single blood glucose reading from a fasting blood glucose or casual blood glucose test is not a good indicator of glycemic control. These tests are still useful, however, as they are both utilized to diagnose diabetes. In addition, people with diabetes use hand-held glucometers to test their blood glucose multiple times per day. The single point-in-time glucometer readings let the patient instantly know his or her blood glucose level at the time the test was performed. Among individuals without diabetes, blood glucose levels rise and fall throughout the day as food is eaten and metabolized. In those with diabetes, this fluctuation in blood glucose levels is usually much wider. It is the patient’s responsibility to use the glucometer readings to maintain control of blood glucose levels, minimize highs and lows, and avoid hypoglycemia.

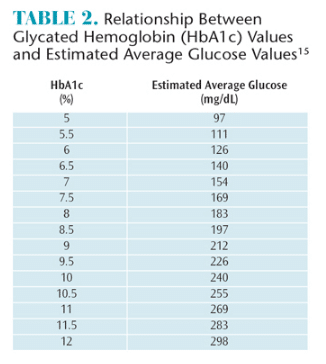

While the HbA1c test averages the glucose over the preceding 2 month to 3 month period, it does not provide an indication of the heights and depths of the peaks and valleys in normal daily blood glucose levels.5,6 In recent years, physicians have altered the way they discuss patients’ glycemic control. People with diabetes use glucometers daily, and the units of measure for glucometers in the US are milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). Thus, patients become familiar with blood glucose readings such as 98 mg/dL and 156 mg/dL. The HbA1c test results are given as a percentage, which maybe confusing for patients. As such, physicians now convert the results of the HbA1c test into an estimated average glucose or eAG (Table 2).5,15 The eAG simply converts the HbA1c percentages into mg/dL, making it easier for patients to interpret the results.

While the HbA1c test averages the glucose over the preceding 2 month to 3 month period, it does not provide an indication of the heights and depths of the peaks and valleys in normal daily blood glucose levels.5,6 In recent years, physicians have altered the way they discuss patients’ glycemic control. People with diabetes use glucometers daily, and the units of measure for glucometers in the US are milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). Thus, patients become familiar with blood glucose readings such as 98 mg/dL and 156 mg/dL. The HbA1c test results are given as a percentage, which maybe confusing for patients. As such, physicians now convert the results of the HbA1c test into an estimated average glucose or eAG (Table 2).5,15 The eAG simply converts the HbA1c percentages into mg/dL, making it easier for patients to interpret the results.

MANAGING DIABETES IN THE DENTAL OFFICE

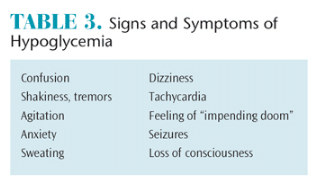

Hypoglycemia is the most common complication of diabetes, particularly among those whose treatment involves insulin therapy.5 Shakiness, sweating, and tachycardia often precede many hypoglycemic reactions, but some events occur without warning. Table 3 provides a list of signs and symptoms.

Risk of hypoglycemia is highest among patients with well-controlled blood glucose levels and low HbA1c because they have lower average daily blood glucose levels.16 Symptoms of hypoglycemia generally present when a patient’s blood glucose levels drop below 60 mg/dL to 70 mg/dL but can also occur at higher levels. Patients with diabetes should have their medication lists screened for drugs that can increase the risk of hypoglycemia before receiving dental treatment.4,16 Oral health professionals should also inquire as to how often patients experience hypoglycemia and if there have been occurrences of hypoglycemia unawareness. This phenomenon occurs when a patient is asymptomatic for hypoglycemia and suddenly experiences an extreme reaction, such as seizure or loss of consciousness.4,17

The easiest way to prevent a hypoglycemic event in the dental office is to ask patients with diabetes to bring their personal glucometers to each dental appointment.16 Prior to the start of treatment, patients should check their blood glucose levels and clinicians should record the results in the treatment notes. Patients should also be asked if they have taken their diabetes medication and when and how much they’ve recently eaten. By making this pretreatment blood glucose evaluation an office policy, the dental team communicates the importance of responsibly managing patients’ diabetes while under its care.16 By asking patients to bring their glucometers to the dental office, oral health professionals are able to take an immediate assessment of blood glucose levels should they begin to exhibit signs or symptoms of hypoglycemia.

If the pretreatment glucometer reading approaches dangerously low levels, patients should consume approximately 15 g of carbohydrates, such as 4 oz to 6 oz of juice, to raise the glucose to a safe range for the duration of the appointment. For example, if the pretreatment glucometer reading is 82 mg/dL before an hour-long procedure, the patient is close to the 60 mg/dL to 70 mg/dL level, at which hypoglycemia symptoms may occur. Therefore, it may be wise to give the patient approximately 15 g of carbohydrates before proceeding. This amount usually raises blood glucose levels by 40 mg/dL to 60 mg/dL in a few minutes.

While the glucometer is an important short-term tool for assessing glucose levels, when determining how well patients’ blood glucose is controlled over the long term, clinicians should request their HbA1c values from the physician.4,16 Obtaining the HbA1c values from their physicians, rather than patients, is important because patients may not always know their most recent percentages, may guess inaccurately, or may generalize the results.

While the glucometer is an important short-term tool for assessing glucose levels, when determining how well patients’ blood glucose is controlled over the long term, clinicians should request their HbA1c values from the physician.4,16 Obtaining the HbA1c values from their physicians, rather than patients, is important because patients may not always know their most recent percentages, may guess inaccurately, or may generalize the results.

Obtaining HbA1c values from the past 2 years to 3 years paints a more accurate picture of patients’ true glycemic control over time. Some people with diabetes have HbA1c values that are stable over many years, while others have widely fluctuating values. Because the HbA1c provides an estimate of the average glucose levels, it offers insight into a patient’s risk of hypoglycemia. In general, the lower the HbA1c value, the higher the risk of hypoglycemia.16,18 For example, an individual with an HbA1c level of 10.5% has an estimated average glucose of about 255 mg/dL. This individual’s average glucose levels are far higher than the level at which hypoglycemia occurs. While hypoglycemia can affect those with high average glucose levels, if the short-term glucose drops precipitously, hypoglycemia is less likely for this patient than one whose HbA1c is 6%, which equates to an estimated average glucose of 126 mg/dL.

CONCLUSION

Oral health care professionals frequently treat patients with diabetes and, thus, need to understand the basics of diabetes management. The HbA1c test is a critical component of assessing the quality of patients’ glycemic control over the long-term. In combination with point-in-time glucometer testing, the HbA1c also provides an assessment of risk for hypoglycemic emergencies in the dental office.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

- Mealey BL, Oates TWI. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J Periodontum. 2006;77:1289–1303.

- Mealey BL, O’Campo GL. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2007;44:127–153.

- Mealey BL. Management of the patient with diabetes mellitus in the dental office. In: Lamster IB, ed. Diabetes Mellitus and Oral Health: An Interprofessional Approach. Ames, Iowa: Wiley Blackwell Inc; 2014:99-–120.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl 1):S8–S11.

- Kaur H, Weinstock RS. Glycemic treatment of diabetes mellitus. In: Lamster IB, ed. Diabetes Mellitus and Oral Health: An Interprofessional Approach. Ames, Iowa: Wiley Blackwell Inc; 2014: 69–95.

- Mealey BL. Periodontal disease and diabetes: A two-way street. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(Suppl 10):26S–31S.

- Lalla E, Cheng B, Lal S, et al. Diabetes-related parameters and periodontal conditions in children. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;42:345–349.

- Taylor GW, Burt BA, Becker MP, et al. Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus and alveolar bone loss progression over 2 years. J Periodontol. 1998:69:76–83.

- Curtis JM, Knowler WC. Classification, epidemiology, diagnosis and risk factors of diabetes. In: Lamster IB, ed. Diabetes Mellitus and Oral Health: An Interprofessional Approach. Ames, Iowa: Wiley Blackwell Inc; 2014:27–44.

- Virtue MA, Furne JK, Nuttall FQ, Levitt MD. Relationship between GHb concentration and erythrocyte survival determined from breath carbon monoxide concentration. Diabetes Care. 2004:27:931–935.

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993:329:977–986.

- U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998:352:837–853.

- Koro CE, Bowlin SJ, Bourgeois N, Fedder DO. Glycemic control from 1988 to 2000 among U.S. adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a preliminary report. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:17–20.

- Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, Zheng H, Schoenfeld D, Heine RJ. Translating the A1c assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1473–1478.

- Mealey BL. Managing patients with diabetes: First, do no harm. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2072–2076.

- Bakatselos SO. Hypoglycemia unawareness. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93 (Suppl 1):S92—S96.

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Hypoglycemia in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes. 1997;46: 271–286.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2015;13(5):45–48.