Debunking Oral Cancer Myths

Oral health professionals are charged with educating their patients about oral cancer risk and detection, as well as ensuring effective screenings are performed at every dental appointment.

This course was published in the April 2014 issue and expires April 30, 2017. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence and risk factors for oral cancer.

- Identify myths about oral cancer that may put patients’ health at risk.

- List the tools available to assist clinicians in the detection of oral cancer.

- Explain how dental hygienists can help patients reduce the risk of oral cancer.

According to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, approximately 157,000 men and 87,000 women had oral cancer in 2004. The Oral Cancer Foundation expects 42,000 new cases of oral cancer to be diagnosed in 2014.1 Early detection increases survival rates to 80% to 90%.2 Over the past 5 years, the number of individuals diagnosed with oral cancer has increased.2,3 While tobacco and alcohol use are well known risk factors, patients may be unaware of others, including: sun exposure; a diet high in red, processed, or fatty meat; low vegetable intake; marijuana use; and exposure to the human papillomavirus (HPV).4–7

Oral health professionals play a key role in risk prevention and early detection of oral cancer.4 Conducting comprehensive health histories should reveal oral cancer risk factors. Dental hygienists are responsible for educating patients about oral cancer risks and assisting them with behavioral/lifestyle changes to reduce such risks.5 One way to capture patients’ attention is to debunk common myths about oral cancer.

MYTH 1: I’M TOO YOUNG TO DEVELOP ORAL CANCER

Many patients believe that oral cancer only affects older adults. While it is true that men in their early 60s have the highest incidence of oral cancer,8 oral cancer rates for those younger than 40 are rising, as young people frequently engage in high-risk behavior—from sexual contact that may lead to HPV transmission to tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use.9

HPV?is transmitted via skin-to-skin contact, most frequently during sexual activity. Exposure to HPV is very common among young adults and teenagers, as the rising popularity of oral sex has greatly increased the virus’ transmission through the oral cavity.10–12 Evidence shows that nearly all incidences of cervical cancer are caused by HPV, specifically types 16 and 18.13 HPV can also be found in cancerous and precancerous lesions in the oral cavity. The presence of HPV 16 is a significant risk factor for oral cancer, and types 6, 7, 33, 35, and 59 have also been found in oral cancer lesions.14 Of those diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancers, 84% test positive for HPV 16.10,15

Two HPV vaccinations—Cervarix and Gardasil—have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Cervarix is available for girls and women while Gardasil can be administered to boys and men, in addition to girls and women. The vaccinations are most effective when the three-shot series is completed before individuals experience their first sexual encounters. As such, both vaccines are recommended for adolescents age 11 or 12. The vaccines are also recommended for the following populations: women/girls age 26 and younger; men/boys age 21 and younger; gay and bisexual men; and men and women with compromised immune systems who are younger than 27. Dental offices can promote awareness of such vaccinations by placing patient education brochures in the reception and operatory areas. Oral health professionals should also be prepared to discuss the need for these vaccinations with their patients.16

Exposure to ultraviolet light, from both natural and artificial (tanning beds) sources, is another risky behavior popular among young people. Historically, prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light has affected those who work primarily outside (farmers, construction workers). Increased access to tanning beds, however, has placed young people at increased risk for head and neck cancers.17

Ultraviolet light exposure can cause cancers of the face and neck, such as melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma—with the former accounting for 60% of deaths among patients with skin cancer.17 Melanoma, when diagnosed early, is curable; however, its ability to metastasize to other sites in the body can result in death.18 Individuals who begin using tanning beds at age 35 or younger are at the greatest risk of melanoma.18,19 Basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas are more common than melanoma, but they are easier to treat.18 Even with this known risk, people continue to use indoor tanning beds, often with the false belief that such usage is safe and creates a “base tan” to reduce the risk of burning.19 When discussing the risk of tanning, oral health professionals can refer to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which states that any exposure to ultraviolet light damages skin cells, putting individuals at increased cancer risk.19 Adolescents are at increased risk due to their rapidly dividing cells.

The CDC reports that approximately 29% of nonHispanic white female high school students have used tanning beds.19 This number jumps to 44% among Midwestern nonHispanic white females between the ages of 18 and 21.19 As such, the CDC’s Healthy People 2020 developed objectives to reduce the use of indoor tanning beds.20 Many states have enacted laws that prohibit the use of tanning beds by minors.19 These laws, however, do not prevent minors from sunbathing—making education about the dangers of ultraviolet light key to reducing skin cancer prevalence. Melanoma can be found on any part of the body that is exposed to the sun’s ultraviolet rays. Because the face is susceptible, clinicians should perform both an extraoral and intraoral exam during the oral cancer screening. Dental hygienists should discuss the risk of sun exposure with all patients, and encourage the use of broad spectrum sunscreens.

Diet is also associated with oral cancer risk. It is estimated that 30% of cancers are related to a diet high in meat and low in vegetables.3 Vegetables and fruits contain essential vitamins that eliminate free oxygen radicals that damage cell DNA. In contrast, consuming processed meats increases exposure to nitrites, which have the potential to convert to carcinogenic nitrosamines.5 In a review of six cohort studies and 40 case studies, Lucenteforte et al6 found an inverse relationship between fruit, vegetable, and whole grain ingestion and oral cancer risk. Vitamin E, vitamin A, foliate, and iron appear to be beneficial to cell health and maintenance.6 In addition, Pavia et al21 determined that the risk of oral cancer is reduced by up to 50% when consuming a diet of fruits and vegetables. Oral health professionals should discuss the effects of poor dietary choices on the oral cavity with their patients.

Tobacco and alcohol use also increase the risk for oral cancer. While the CDC reports an overall decline in tobacco use, young adults are still engaging in this risky behavior—with 16% of female and 20% of male high school students reporting smoking one or more cigarettes per month in 2011.22 In addition, teenagers who use tobacco are more likely to participate in other risky behaviors, including: smoking marijuana, drinking alcohol, or engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse.22 Young adults who partake in more than one at-risk behavior have a 15% higher risk for oral cancers than those who participate in only one.1,22 The American Institute for Cancer Research states that tobacco use is the major cause of head and neck cancers, with alcohol a close second, and that abstaining from both behaviors is the best way to prevent these cancers.23

Marijuana use increases the risk of oral cancer. The State Youth Risk Behavior Survey states that approximately 40% of high school students have tried marijuana. This behavior, however, is often used in combination with other risk factors (tobacco, alcohol use), making it difficult to directly link marijuana to oral cancer.24 Precancerous lesions, such as leukoplakia and erythroplakia, have been associated with marijuana use.24 With the legalization of marijuana in some states, its use may increase, which could result in a growing number of patients presenting with marijuana-associated lesions.

Clinicians should educate young patients on the potential long-term health risks of marijuana use, such as impairment of judgment and memory abilities, respiratory problems, and increased susceptibility to lung infections.22,25 Many marijuana users begin smoking the drug in high school, which is a time of intense brain development.26 Meier et al27 found that those who smoked marijuana heavily while teenagers lost about eight IQ points between the ages of 13 and 38. More long-term studies are needed on the oral cancer risk of adolescent marijuana use.

Educating patients on the oral cancer risks from sexual behaviors, tanning, diet, and use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana should be part of dental hygiene care. Therefore, remaining current on available data and resources is part of the standard of care in preventing oral cancer.

MYTH 2: I HAVE NO PAIN SO THERE IS NO PROBLEM

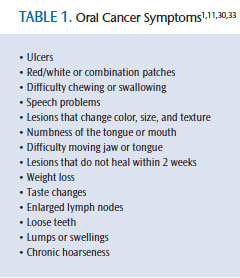

Some oral cancer symptoms (Table 1) may not cause pain and remain inconspicuous, which can lead to precancerous lesions being overlooked.11,28,29 Unfortunately, patients may self-treat minor infections with over-the-counter medications—impeding the chance for early diagnosis.10,30 Cancer may progress without obvious symptoms, thereby delaying early treatment—which is necessary for improved survival rates.1

Oral cancer screenings should be conducted by dental hygienists and dentists to identify inconspicuous lesions overlooked by patients. In addition, oral health professionals should educate patients on what to look for and how to conduct an oral cancer self-screening. Clinicians should specify which areas in the oral cavity are more likely to manifest lesions, and how to examine them. This includes examination of the palate, floor of the mouth, tongue, cheeks, and lips.31,32 Patients should look for lesion changes in color, shape, and size. Lesions that do not heal within 2 weeks should be biopsied. Patients with chronic lesions should be encouraged to receive follow-up care; long-term ulcerative lesions have the potential to become malignant.

MYTH 3: MY DENTAL PROFESSIONAL WILL FIND ORAL CANCER LESIONS EARLY

Patients expect oral health professionals to be knowledgeable in identifying potential cancerous lesions; however, oral cancer examinations are not always conducted at routine dental appointments. This must change, as the early detection of oral cancers increases life expectancy by 80%, compared to a 30% survival rate for late-stage oral cancer diagnosis.33 Oral cancer screening examinations are an excellent opportunity for clinicians to educate patients on risk factors, symptoms, and prevention methods.

Bigelow et al34 surveyed dental hygienists in Maryland and North Carolina, and identified reasons why oral cancer screening exams were not performed regularly. Dental hygienists indicated there is not enough time to perform the screenings; they lack confidence in performing the procedure correctly; and some felt the dentist did not require this service.34

Bell et al35 surveyed 859 dental hygienists and found that 89% did perform regular oral cancer screenings but that still leaves 11% who are not conducting this lifesaving exam. Continuing education opportunities are possible solutions to prepare dental hygienists to perform these lifesaving examinations. Cotter et al4 found dental hygienists who attended continuing education courses in oral cancer detection were significantly more likely to perform oral cancer screenings. Every office should have a protocol that includes an oral cancer screening exam performed by both the dentist and dental hygienist.

The patient should be told each time an oral cancer screening is performed. Each patient chart should have an area for documentation of identified lesions in order to compare against baseline data. Dental hygienists should be responsible for identifying, documenting, and following up on suspicious lesions. The oral cancer screening protocol should also include communication to the patient about the next steps, such as a biopsy or referral to a specialist. Intraoral cameras are an excellent tool to document early lesions and for comparison purposes at future visits. Documentation and follow up are key to improving early detection rates.

EARLY DETECTION TECHNIQUES

Oral health professionals need to be familiar with the techniques available for early detection of oral cancer. Conventional oral examination, risk assessment, light-based detection systems, brush biopsy, and self-oral examinations are some of the tools used to detect oral cancers.

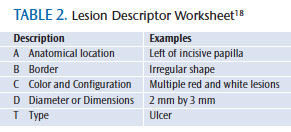

Conventional oral examinations are traditional visual exams that use incandescent overhead light or a light attached to magnification glasses.29 This type of examination is part of the standard of care and should be performed on every patient. A dental office policy that outlines how to perform a conventional oral examination and document suspicious lesions can be helpful for consistency in performing a comprehensive exam. Palpating and using magnification with lighting to examine the palate, floor of the mouth, tongue, lips, and oropharynx for abnormalities, followed by documenting lesions on a worksheet included in every chart are important parts of traditional oral cancer screening.29 A lesion descriptor worksheet may be used by clinicians to identify suspicious lesions.18 Table 2 summarizes the specific categories to ensure a written description will communicate the specifics of a lesion to other clinicians—making the lesion easy to find and monitor. A small percentage of precancerous lesions may not be detected by conventional oral cancer examinations. The use of other diagnostic tools may help supplement a visual exam.29

Software programs are available that will calculate patients’ risk for oral cancer and provide a printed report on these risk factors.35 Patients complete a printed survey, from which the dental hygienist inputs the data and the program creates a customized risk assessment report.36 Dental hygienists can use this information to reinforce oral cancer prevention recommendations.

Light-based detection systems are also used by clinicians to detect oral cancer lesions.29,36 Some systems use a 1% acetic acid mouthrinse to remove surface debris and expose epithelial cell nuclei.29,36 A light source is then used to examine the oral mucosa. Abnormal epithelial cells will appear white, while normal tissue appears blue. One technology uses a tolonium chloride solution to mark the lesion, which remains visible after the light source is removed to facilitate biopsy.29,36

Another light-based detection system uses a handpiece to emit an intense blue excitation light that is either absorbed by the tissue or reflected.29 Cells in healthy tissue absorb the blue light, fluoresce, and appear green. Abnormal cells do not fluoresce and appear dark.29

Light-based detection systems are easy to use and provide noninvasive methods to assist clinicians in finding abnormal tissue.29 They do not, however, provide a definitive diagnosis. Patients with abnormal tissue should be referred to an oral surgeon for biopsy. A panel by the American Dental Association concluded that the studies on light-based systems have not provided enough data to prove they are better at diagnosing premalignant lesions than conventional oral cancer screening.37

A brush biopsy is another technique for evaluating suspicious oral lesions. Only a surface sample (to the epithelial basement membrane) is necessary, resulting in less pain than incision biopsies.36 The sample is sent to a lab to determine if the cells are abnormal or dysplastic.36 This test can be used in combination with conventional oral cancer screening or other techniques. When results show abnormal or dysplastic tissue, patients should be referred to a specialist for biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

Lastly, showing patients how to perform a self-oral cancer examination empowers them to be proactive in identifying abnormal lesions in their earliest stage. Patients should examine their head, neck, face, lips, cheeks, and floor and roof of the mouth for lesions that appear different from surrounding tissue.31,32 Dental hygienists can print self-assessment guides from the American Dental Hygienists’ Association website (adha.org) for patients to reference at home.31

CLINICAL APPLICATION

Due to the limited time that dental hygienists have with patients, it may be challenging to incorporate many of these oral cancer screening methods. However, the conventional examination can be completed in just a few minutes, and information about diet and other oral cancer risks can be provided during patient education. Oral health professionals can also give patients handouts containing links to websites with additional oral cancer prevention information. Because oral cancer screening examinations with devices can add additional costs to the appointment, patients should be informed about the expense, insurance coverage, and how these methods for early detection of precancerous lesions are used to improve the chances of successful treatment. Once the patient agrees to the supplemental screening tool, a separate, brief appointment may be scheduled to conduct the screening.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists must include an oral cancer screening as part of the standard of care. Educating patients on the common myths regarding oral cancer can start a conversation that enables patients to be more involved in early detection. In addition, enhancing oral cancer screening with advanced technologies may aid in identifying oral cancer at its earliest stages, which greatly improves survival rates. Performing these life-saving screenings during routine care allows for consistency and takes very little time. In addition, some tests have dental insurance codes that may help defray associated cost.

Patients must be proactive in maintaining their oral health and request that dental professionals perform regular oral cancer screenings. Dental hygienists should provide effective patient education on oral cancer risk. But the bottom line is that oral health professionals should perform oral cancer screenings on every patient, regardless of risk, in order to improve the probability of early detection.

REFERENCES

- Oral Cancer Foundation. Oral cancer facts. Available at: oralcancerfoundation.org/ facts/index.htm. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- Oral Cancer Foundation. Homepage. Available at: oralcancerfoundation.org. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. Cancer Fact Sheet. Available at: atsdr.cdc.gov/ COM/cancer-fs.html. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- Cotter JC, McCann AL, Schneiderman ED, De Wald JP, Campbelle PR. Factors affecting the performance of oral cancer screenings by Texas dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2011;85:326–334.

- Chainani-Wu N, Epstein J, Touger-Decker R. Diet and prevention of oral cancer: strategies for clinical practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:166–169.

- Lucenteforte E, Garavello W, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C. Dietary factors and oral and pharyngeal cancer risk. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:461–467.

- Helen-Ng LC, Razak IA, Ghani WM, et al. Dietary pattern and oral cancer risk–a factor analysis study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:560–566.

- American Cancer Society. Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancer Statistics. Available at: cancer.org/cancer/oralcavityandoropharyngealcancer/detailedguide/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- Raychowdhury S, Lohrmann DK. Oral cancer risk behaviors among Indiana college students: a formative research study. J Am Coll Health. 2008;57:373–377.

- Callaway C. Rethinking the head and neck cancer population: the human papillomavirus association. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;15:165–170.

- Hewett J. Oral cancer: diagnosis, management and nursing care. Nursing Practice. 2009;8:28–34.

- Sanders AE, Slade GD, Patton LL. National prevalence of oral HPV infection and related risk factors in the US adult population. Oral Dis. 2012;18:430–441.

- Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007; 370:890–907.

- Al-Bakkal G, Ficarra G, McNeill K, Eversole LR, Sterrantino G, Birek C. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene expression in oral exophytic epithelial lesions as detected by in situ rtPCR. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:197–208.

- Duncan LD, Winkler M, Carlson ER, Heidel RE, Kang E, Webb D. P16 immunohistochemistry can be used to detect human papillomavirus in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1367–1375.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV?Vaccinations. Available at: cdc.gov/hpv/ vaccine.html. Accessed March 11, 2014.

- Zhang M, Qureshi AA, Geller AC, Frazier L, Hunter DJ, Han J. Use of tanning beds and incidence of skin cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1588–1593.

- Nield-Gehrig JS. Patient Assessment Tutorials: A Step-By-Step Guide for the Dental Hygienist. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:348–385.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Skin Cancer: Is Indoor Tanning Safe? Available at: cdc.gov/cancer/skin/basic_info/indoor_tanning.htm. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- HealthyPeople.gov: US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. 2020 Topics & Objectives (Objective A-Z). Available at: healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- Pavia M, Peleggi C, Nobile C, Angelilo IF. Association between fruit and vegetable consumption and oral cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1126–1134.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking & Tobacco Use: Youth and Tobacco Youth. Available at: cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/tobacco_use. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- American Institute for Cancer Research. Recommendations for Cancer Prevention. Available at: aicr.org/reduce-your-cancer-risk/recommendations-for-cancer-prevention. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- Marks MA1, Chaturvedi AK, Kelsey K, et al. Association of marijuana smoking with oropharyngeal and oral tongue cancers: pooled analysis from the INHANCE consortium. i. 2014;23:160–171.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Facts: Marijuana. Available at: drugabuse.gov/ publications/drugfacts/marijuana. Accessed March 11, 2014.

- Griffin KW, Bang H, Botvin GJ. Age of alcohol and marijuana use onset predicts weekly substance use and related psychosocial problems during young adulthood. i. 2010;15(3):174–183.

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2657–26564.

- Pentenero M, Navone R, Motta F, et al. Clinical features of microinvasive stage I oral carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2011;17:298–303.

- Lingen MW, Kalmar JR, Karrison T, Speight PM. Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:10–22.

- Newland JR, Meiller TF, Wynn RL, Crossley HL. Oral Soft Tissue Diseases. 6th ed. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp Inc; 2013:14–15.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Want some life saving advice? Available at: adha.org/resourcesdocs/7231_Oral_Cancer_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2014.

- DeLong L, Burkhart N. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:105–106.

- Walsh MM, Rankin KV, Silverman S Jr. Influence of continuing education on dental hygienists’ knowledge and behavior related to oral cancer screening and tobacco cessation. J Dent Hyg. 2013;87:95–105.

- Bigelow C, Patton L, Strauss R, Wilder R. North Carolina dental hygienists’ view on oral cancer control. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:83.

- Bell K, Phillips C, Paquette D, Offenbacher S, Wilder R. Incorporating oral-systemic evidence into patient care: practice behaviors and barriers of North Carolina dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2011;85:99–113.

- DiGangi P. Life-saving oral cancer prevention and detection tools. Available at: dentaleconomics.com/articles/print/volume-98/issue-6/features/life-saving-oral-cancer-prevention-and-detection-tools.html. Accessed March 22, 2014.

- Rethman MP, Carpenter W, Cohen EE, et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding screening for oral squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:509-520.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2014;12(4):65–68.