Consider the Cost

Oral health professionals need to address the financial side of esthetic dental treatment when discussing options with older adults.

The number of older adults in the United States is growing at an unprecedented rate.1 In 2011, the earliest members of the baby boomer generation—those born between 1946 and 1964—turned 65 and became eligible for Medicare.1 In 2056, it is projected that, for the first time in recorded history, the number of individuals age 65 and older will be greater than those age 18 and younger.2 As the population of older adults grows, so does the demand for oral health care services.3 Most older adults experience the same dental needs as the general population (eg, prevention, risk management, restorative care). The ability of this population to receive professional dental care, however, is often limited, particularly for older adults who are home-bound, living in long-term care facilities, or medically compromised.4

The cost of care also may present a challenge.5 Most older adults in the US pay out of pocket for elective dental treatment.6 These costs greatly impact individuals’ decision making on what type of care will be obtained.7,8 The large number of treatment options can also be daunting for this population.2 Clinicians should use a personalized approach that considers risks and remaining teeth and bone when advising patients on treatment options.9

Clinicians are charged with helping older adults navigate the many esthetic options available in contemporary restorative dentistry. Generally, the question many older adults face is which option offers the best combination of esthetics and longevity for the lowest cost. This article will focus on the esthetics and expenses involved in this decision-making process. Longevity is dependent on the level of functional risk and varies considerably from patient to patient.

There is no dental treatment that is precluded by age alone; however, there are many coexisting factors that may impact the course of dental treatment for older adults. Cost, patient desires and beliefs, patient dental and medical history, invasiveness and longevity of treatment, and oral health status are considerations that may affect the type and extent of dental treatment. Clinicians are often faced with a quandary in which their patient needs or desires a complex and esthetic restoration but has limited financial resources to pay for that treatment. Fortunately, there is a range of restorative options that may be able to fulfill a patient’s functional and esthetic requirements.

RESTORATIVE MATERIALS

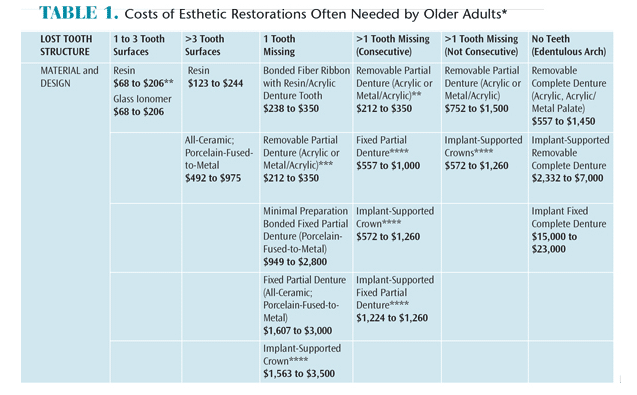

Materials for replacing missing teeth can be attached to existing adjacent teeth (bridges), part of removable complete dentures or partial dentures, or supported by implants. Table 1 includes the full range of these restorative options, as well as the associated costs. Older adults with limited resources should be advised that dental schools offer low-cost opportunities for care. The lower prices listed in the table are for care provided by dental students at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in April 2014. The higher costs are for services provided in an established private dental practice in Ann Arbor. Of course, prices vary considerably throughout the US. New fabrication methods are being developed each day, so costs typically decrease with time. This range of costs for treatment provides a reference for individuals considering options among different procedures and providers.

**Costs vary based on the materials chosen and method of fabrication (eg, laboratory, computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing, or chairside). The lower prices are the cost of services provided at the University of Michigan’s School of Dentistry in the dental student clinics in April 2014. The other prices are average costs of services provided in a general practice in Ann Arbor, Michigan in April 2014.

***Not recommended due to aspiration/choking risk.

****Per tooth, implant/abutment costs not included in price

MAKING CHOICES

Table 1 can be used to help older adults make educated decisions about the dental care they will receive. The following examples encompass typical patient scenarios that clinicians are most likely to encounter. By working with patients and considering the constraints of their finances, options should be selected within the relevant column.

Case 1 is a 72-year-old man with a broken upper front tooth. The patient is mostly dentate, particularly in anterior segments. A clinical examination reveals that tooth #8 is fractured at an oblique angle and approximately two-thirds of a crown is missing. Testing reveals a vital tooth with no pulp exposure and the tooth is asymptomatic, aside from transient mild dentin sensitivity in response to extreme temperatures. There is adequate interocclusal space and interdental space for a restoration, with enough bone and ridge height and width. There are no other contraindications to dental care. The treatment options include the following:

- Composite resin ($123 to $244)

- All-ceramic or porcelain-fused-to-metal crown ($492 to $975)

The full-coverage crown option has the best long-term prognosis and is better able to withstand the incising forces during function. If expense is a major confounder, however, the patient should be informed that a resin restoration will suffice for a shorter duration and with somewhat careful attention paid to the distribution of forces while incising hard foods, such as raw vegetables. Either option is an acceptable way to restore the lost tooth structure and esthetics. Discussing these risks and benefits with the patient will help him choose the option that best fits his desires and resources.

Case 2 is an 80-year-old woman with an upper lateral incisor (#7) fracture at the gum line. The radiograph indicates that the tooth is abscessed and has a very short root. As a result, the tooth is not restorable and needs to be extracted. Her treatment options include:

- Extract the tooth ($73 to $150) and leave the space

- Replace the tooth with a bonded fiber ribbon that includes an acrylic denture tooth ($238 to $350)

- Replace the tooth with an acrylic partial denture ($212 to $350)

- Replace the tooth with a bonded, fixed partial denture ($949 to $2,800)

- Replace the tooth with a fixed partial denture bridge ($1,607 to $3,000)

- Replace the tooth with an implant-supported crown ($1,563 to $3,500)

If the patient truly desires to replace the lost tooth, then the question is which option provides the best long-term prognosis? The implant-supported crown is the choice for maximal esthetics and best long-term prognosis. This choice also rules out a removable prosthesis or a fixed prosthesis requiring supplemental hygiene aids and techniques. It is, however, the most expensive option. If finances are a significant concern, then the patient needs to decide which of the remaining options—typically 2, 3, or 4—will offer the best risk-to-benefit ratio for the money. This varies based on individual patient factors and requires a thorough discussion with the patient, reviewing risks and benefits for each option.

A third example involves a 67-year-old woman with a broken tooth on the upper left that is very sensitive. Her exam reveals that she has fractured the buccal cusp of tooth #13. Radiographic evaluation indicates no periapical pathology. She states that she has limited financial ability. Her treatment options are:

- Extraction without replacement ($73 to $150)

- Pin-retained or bonded composite resin ($168 to $274)

- Core buildup ($123 to $244) with an all-ceramic or porcelain-fused-to-metal crown ($492 to $975)

This case presents the most difficult situation. Clearly, the best option is to restore the tooth (option 3) for function, longevity, and esthetics. If this option is too expensive, the remaining choice (option 2) is a compromise on longevity. Often, a patient will ask if there is a way to keep the tooth a little longer in order to put off the extraction until the procedure becomes more financially feasible. In this situation, a compromise should be provided. Realistically, the patient and the clinician both know that the tooth will need to be extracted—probably sooner vs later. Nonetheless, option 2 will allow the patient to maintain the tooth for esthetics and function, even though the prognosis is, at best, fair.

The final case is a 78-year-old man with a loose bridge who has not seen a dentist in several years. The exam reveals that he has a bridge from tooth #6 to #11, which is loose on #11. A radiograph reveals the tooth is abscessed with decay extending below the bone. The diagnosis for tooth #11 is nonrestorable, and the tooth must be extracted. The patient has very limited income. The initial treatment recommendation would be to cut the bridge apart between #6 and #7 and extract #11. Final treatment options are:

- Do not restore—leave the patient edentulous from #7 to #12

- Restore with an all-acrylic partial denture ($212 to $350)

- Replace the teeth with an all metal/acrylic removable partial denture ($752 to $1,500)

- Replace the teeth with three implants and restore with a bridge ($13,800)

Because the patient has very limited income, only options 1 and 2 are realistic to consider. While leaving the space edentulous is certainly the least expensive, this would severely compromise the patient’s esthetics and ability to incise. Yet, if the patient does not have the ability to finance any other treatment, does not value esthetics, and is able to accommodate the loss of function, then option 1 may be the best choice. Oral health professionals must remember that restoring esthetics and function fall under corrective measures and, while valuable, do not supersede their obligation to control disease.

SUMMARY

Older patients living on fixed incomes who finance most or all of their dental expenses out of pocket need to understand the potential options for esthetic restorative care and the relative costs. As can be seen by the aforementioned examples, many options are available that vary in their level of esthetics, function, longevity, and cost. It is up to the patient and dental health care provider to discuss the risks and benefits associated with each option to determine the best strategy for the patient. Dental hygienists are well suited to provide this information and support this patient population during the decision-making process.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The State of Aging and Health in America 2013. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

- United States Census Bureau. US Census Bureau Projections Show a Slower Growing, Older, More Diverse Nation a Half Century from Now. Available at: census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- Waldman HB, Truhlar MR. Increasing population, limited dental insurance, but increasing use of services. NY State Dent J. 2010;76:50–52.

- Dolan TA, Atchison K, Huynh TN. Access to dental care among older adults in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:961–974.

- Jones JA, Adelson R, Niessen LC, Gilbert GH. Issues in financing dental care for the elderly. J Public Health Dent. 1990;50:268–275.

- Niessen LC, Douglass CW. Application of a needs-based model for planning geriatric dental services for the Veterans Administration. Spec Care Dent. 1985;5:78–83.

- Issrani R, Ammanagi R, Keluskar V. Geriatric dentistry—meet the need. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e1–e5.

- Bock JO, Matschinger H, Brenner H, et al. Inequalities in out-of-pocket payments for health care services among elderly Germans—results of a population-based cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:3–11.

- Biber CL, Cinotti WR, Iacopino AM. The geriatric patient: evaluation, treatment planning, affordable concepts. J N J Dent Assoc. 1989;60:59–64.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2015;13(1):40–43