FOTOCUISINETTE/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

FOTOCUISINETTE/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Caring for the Transgender Patient

Oral health professionals should be prepared to provide equitable care to this often stigmatized population.

This course was published in the January 2020 issue and expires January 2023. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the common terms chosen by transgender individuals to describe their gender identity.

- Describe barriers to care experienced by transgender individuals.

- Discuss health concerns specific to transgender patients.

- Explain the transfriendly dental office environment necessary for culturally competent care of this patient population.

Recent reports estimate that 0.6% of adults in the United States, or approximately 1.4 million people, and 0.7% or 150,000 adolescents identify as transgender.1 Of those ages 13 and older who identify as transgender in the US, 10% are youth (13 to 17), 13% are young adults (18 to 24), 63% are ages 25 to 64, and 14% are ages 65 and older.1 Although transgender children (younger than 13) most likely comprise a small number, some are now more likely to transition at younger ages than in the past because of greater public awareness and growing acceptance.2 As the transgender population grows, the provision of culturally competent care is integral to these patients achieving and maintaining oral health.

DEFINITIONS

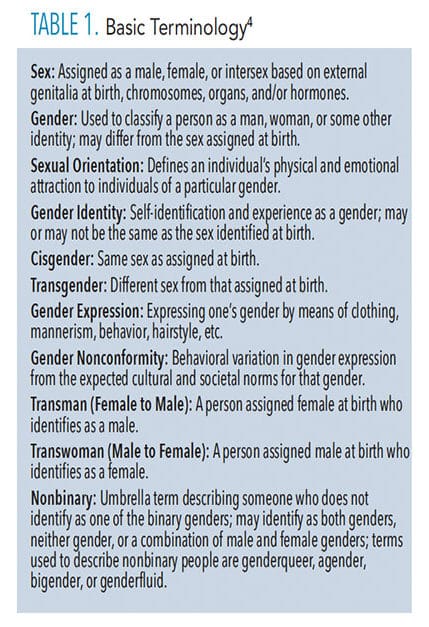

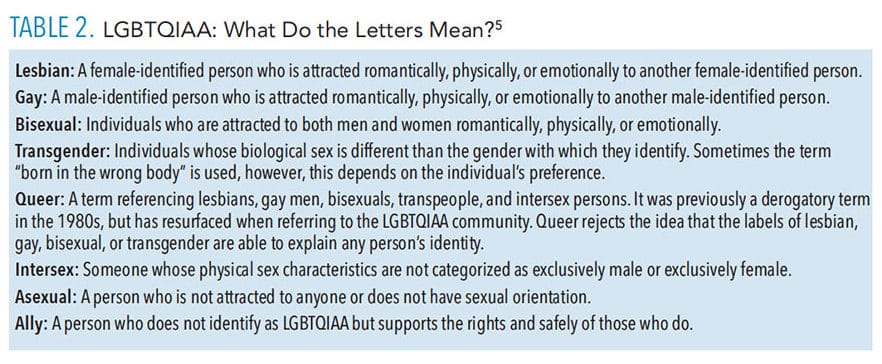

The assignment of sex at birth is based on the physical appearances of the external genitals. Genitalia are determined in utero by chromosomal type, but gender identity is an individual’s perceived identity, which may not be the same as the one assigned at birth. Transgender is an all-inclusive term that includes individuals whose gender identity does not align with their assigned birth sex and/or those whose gender identity is outside of the male/female classification.

Cisgender is the term for those whose gender identity or expression aligns with their assigned birth sex.3 An older term, “transsexual” refers to those who identify as transgender and use medical and/or surgical means to physically transition. The term “transsexual” has been replaced with “transgender.” Table 1 and Table 2 provide a glossary of relevant terms.4,5

Most transgender people change their names and prefer to use pronouns that reflect their gender identity (he/him/his for transmen and she/her/hers for transwomen).4 For example, if a biologically male patient identifies as transgender, she probably wants to use female pronouns. This is not always the case, however, as some people prefer gender-neutral pronouns such as they, zhe, thon, etc. English is not the only language expanding to include multiple gender identities. Sweden recently added “hen,” a gender-neutral pronoun that can be used to represent he (han) or she (hon) into their official dictionary.5

Gender dysphoria is when a person experiences discomfort or distress because there’s a mismatch between his or her biological sex and gender identity. It’s sometimes known as gender identity disorder, gender incongruence, or transgenderism. The cause of gender dysphoria is unknown. Hormones in the womb, genes, and cultural and environmental factors are thought to be involved.6 In a landmark decision in May 2019, the World Health Organization removed gender identity disorder from its list of mental health diagnoses. Now called “gender incongruence,” gender identity disorder is classified as a “condition related to sexual health.” In many countries, transgender people must be diagnosed with a gender identity disorder to be approved for various aspects of their transition—from changing their name to undergoing gender confirmation surgery. The reclassification may allow transgender people to seek medical care without being considered “mentally disordered.”7

There are many evidence-based medical options for people seeking treatment for gender incongruence.1 Cross-sex hormones and/or surgeries can be part of the transition process, but neither intervention is universally covered by insurance companies in the US. Some transgender people may seek medical treatment to affirm their gender identity.8 The first step in providing patient-centered care is to be educated about transitioning and the unique health care needs presented by this population.6

Not all transgender people take hormones. According to the National Center for Transgender Equality’s survey of 6,456 transgender individuals, about 62% of respondents reported taking hormone therapy and 23% expressed a desire to have hormone therapy in the future.9 Transgender women reported using hormones at higher rates (80%) than transgender men (69%). Also, not all transgender people on hormone therapy decide to undergo gender reassignment surgery.9

For those who wish to medically transition, treatment includes four types of interventions:

- Changes in social expression of gender to achieve consistency with gender identity

- Therapy with cross-sex hormones to achieve desired masculinization or feminization

- Surgical change of the genitalia and/or other sex characteristics

- Psychotherapy to further explore gender identity, improve body image, and promote resilience

The goal of psychotherapeutic, endocrine, or surgical therapy is lasting personal comfort with the gendered self in order to maximize overall well-being.10 Research shows that 78% of transgender individuals who underwent gender transition reported a higher quality of life.10

BARRIERS TO CARE

Despite gains in civil rights and media attention, transgender individuals still experience health and social disparities across the globe.11 They face multiple obstacles to accessing quality health care, including blatant discrimination and refusal to provide care, as well as a lack of relevant clinical and cultural competence among providers.12

Transgender health care is not a routine component of health professions’ school curricula, so providers are not prepared to provide competent care. This lack of preparation threatens the quality of patient–provider communication and reinforces a treatment system that is designed to be unresponsive to the health needs of this population.9–12 Insensitive and insulting comments and lack of transfriendly health care environments can pose additional barriers to care. Due to these barriers, many try to provide their own care, which can lead to higher risks of illness.

The stigma of transgenderism can cause high rates of unemployment, homelessness, depression, anxiety, family rejection, discrimination, physical and mental abuse, suicide risk, substance abuse, and risky behaviors leading to serious illnesses, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.6,7,13 Many in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and ally (LGBTQIAA) community have been affected by the HIV/AIDS crisis. Even those who are not HIV positive may experience trauma and survivors’ guilt through the deaths of friends, partners, and loved ones. This can have serious consequences for physical health, mental health, and aging, which providers need to be prepared to address.14

Members of the LGBTQIAA are at increased risk for mental health issues, in part due to a lack of societal and family acceptance.14,15 According to a study conducted at the University of Washington in Seattle, individuals who receive family support during their transition exhibit no increase in depression and only a slight increase in anxiety compared with their peers who received no support.16

BRIDGING THE HEALTH CARE GAP

Lack of research and evidence-based guidelines regarding specific health care needs of transgender individuals cause a gap in services. The absence of research to determine cardiovascular disease risk factors in transgender populations receiving cross-sex hormone therapy hinders appropriate care.17 One issue is that this population tends to have many health care providers so while one physician is charged with managing hormones for gender transition another provider is responsible for general health care. Unless there is effective communication between the two, this can be problematic. Risks from the long-term use of cross-sex hormones include but are not limited to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and osteoporosis.6

Sexual orientation and gender identity are not commonly addressed in health care educational programs.14 This lack of knowledge creates a structural barrier to care for transgender people. Transgender individuals often find themselves trying to teach their medical providers how to care for them.9 Lack of knowledge about their health care needs also fosters a mistrust of health professionals, which can lead to an avoidance of care. These structural factors cause transgender people to withhold pertinent information about their sexual orientation, illness, and health behaviors, which then hinders effective treatment and care discussions as well as informed decision making. All of the above factors contribute to poorer health outcomes than cisgender people.9

MEDICAL AND ORAL HEALTH CARE ISSUES

More research is needed on the long-term effects of hormonal therapy. As cross-sex hormones administered for gender affirmation are delivered at high doses over decades, the carcinogenicity of hormonal therapy in transgender people must be considered.8 In addition, concerns regarding cancer risk in transgender patients have been linked to sexually transmitted infections, increased exposure to risk factors such as smoking and alcohol use, and the lack of adequate access to preventive health screening.8 Another potential area of confusion for medical personnel lies in the screening for cancer risk and prevention. Transgender individuals who have not undergone gender changing surgeries or used hormonal therapy should be tested for prostate, breast, and cervical cancer according to guidelines established for their birth sex.6

Due to the high cost of medications used in transitioning, some people purchase them illegally, which they are unlikely to disclose on medical history forms. Clinicians should be aware of this phenomenon and proactively help transgender individuals by inquiring about self-prescribing of hormones, providing information, and referring to the most appropriate center for treatment.7

The presence and severity of dental diseases may vary from one individual to another and are also affected by gender, knowledge, attitude, and ability to access professional oral health care. Neglect of oral diseases can lead to loss of teeth and also negatively impact quality of life. The social stigma associated with LGBTQIAA communities may affect their access to oral health care, and special attention is needed to improve their oral health.18

![]() CREATING A TRANSFRIENDLY OFFICE ENVIRONMENT

CREATING A TRANSFRIENDLY OFFICE ENVIRONMENT

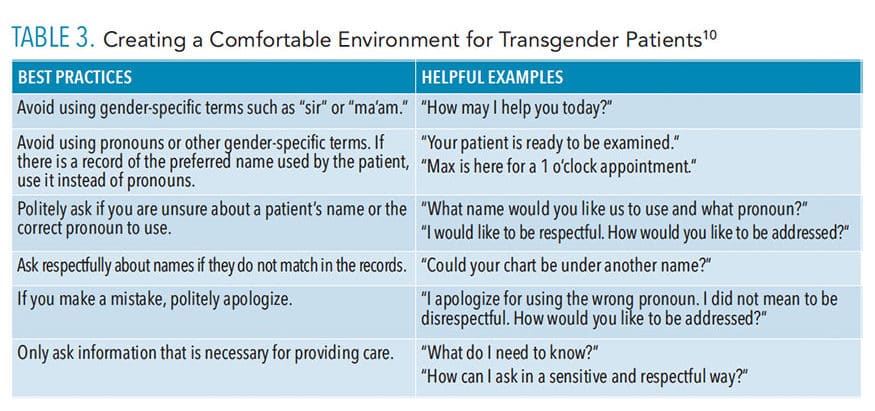

Other key reasons why transgender patients report postponing medically necessary care include stigmatization and discrimination, inability to afford care, and fear of being refused care because of their gender status.13 To combat stigmatization and discrimination, all patient records including electronic medical records (EMR) should include preferred name, pronoun preference, assigned sex at birth, and gender identity.

EMRs and patient identification labels generally use a patient’s legal name, birth date, and a medical record number as key identifiers. Although the legal name is most often used in EMRs, many patients have a preferred name that differs from their legal first name. This may be a nickname, use of a middle name, or another name altogether. For transgender patients, the preferred name may match their affirmed gender or be a different gender than the name assigned at birth. Using a transgender person’s preferred name will create a positive atmosphere for this population.4 If a provider is unsure how to address a patient, using the last name in a reception room and then asking for a preferred name and pronoun in the treatment room are acceptable. It may be uncomfortable at first, but an open and honest conversation is better than unintentionally offending patients.9,10 (Table 3).

The inability to afford care due to a lack of medical insurance and/or the reliance on public assistance often forces transgender individuals to limit or forgo routine care. This avoidance can bring about disastrous results that may further complicate existing conditions or create new ones. As with any patient with limited access to care, staff should provide alternative settings that will provide care for transgender patients when a referral is needed. Making sure the referral office/clinic will accommodate the patient’s needs in a compassionate way will help build trust and allow the patient to receive appropriate care.10–12

![]() CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Students in health professions programs report feeling underprepared for working with patients who identify as LGBTQIAA. This highlights the need for comprehensive training to address their health care needs.12 Including LGBTQIAA competencies in all health care programs will help the next generation of health care providers create a transfriendly environment in their practices. Research on LGBTQIAA issues has dramatically increased over the past 20 years among most health care disciplines. This has led to evidence-based interventions that significantly improve health outcomes, minimize health disparities, improve quality of life, improve self-efficacy, and increase patient and provider education. Oral health professionals are charged with helping lead the way in creating a welcoming environment in providing empathetic, compassionate care to all patients.19

A lack of education and experience has been the major reason for dental professionals’ reluctance to care for patients from stigmatized populations. Focused continuing education programs and exposure in community-based programs are effective in improving access to care.20 Integrating the topic of sexuality throughout curricula may help in increasing students’ sensitivity and comfort levels with LGBTQIAA issues. Adding an interdisciplinary approach would also increase awareness. Expanding the curriculum hours for professional ethics and a code of conduct related to the principle of social justice may also be helpful in providing equitable care to all patients. Dental and dental hygiene school faculty members and administrators have an important role and responsibility for developing curricula that demarginalizes stigmatized populations, promotes professionalism and ethics in students, and ensures future oral health professionals are well prepared to treat patients without prejudice and discrimination.20

REFERENCES

- Gupta S, Imborek KL, Krasowski MD. Challenges in transgender healthcare: the pathology perspective. Lab Med. 2016;47:180–188.

- Milrod C. How young is too young: ethical concerns in genital surgery of the transgender MTF adolescent. J Sex Med. 2014;11:338–346.

- The Williams Institute. New Estimates Show that 150,000 Youth Ages 13 to 17 Identify as Transgender in the US. Available at: williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/transgender-issues/new-estimates-show-that-150000-youth-ages-13-to-17-identify-as-transgender-in-the-us/. Accessed December 13, 2019.

- Imborek KL, Nisly NL, Hesseltine MJ, et al. Preferred names, preferred pronouns, and gender identity in the electronic medical record and laboratory information system: is pathology ready? J Pathol Inform. 2017;8:42.

- Queer Grace. L, G, B, T, Q, Q, I, A… What Do All the Letters Mean? Available at: http://queergrace.com/letters/. Accessed Decemer 13, 2019.

- Sedlak CA, Veney AJ, O’Bryan Doheny M. Caring for the transgender individual. Orthopaedic Nursing. 2016;35(5):301–306.

- Metastasio A, Negri A, Martinotti G, Corazza O. Transitioning bodies. the case of self-prescribing sexual hormones in gender affirmation in individuals attending psychiatric services. Brain Sci. 2018;8:88.

- Braun H, Nash R, Tangpricha V, Brockman J, Ward K, Goodman M. Cancer in transgender people: evidence and methodological considerations. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39:93–107.

- Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C. Barriers to care among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Milbank Q. 2017;95:726–748.

- National LGBT Health Education Center. Affirmative Care for Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People: Best Practices for Front-Line Health Care Staff. Available at: lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/13-017_TransBestPracticesforFrontlineStaff_v9_04-30-13-1.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2019.

- Makadon H, Potter J, Mayer K, Goldhammer H. The Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. 2nd ed. Boston: American College of Physicians; 2015.

- Beagan B, Fredericks E, Bryson M. Family physician perceptions of working with LGBTQ patients: physician training needs. Can Med Educ J. 2015;6:e14–e22.

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis T, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: a Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Available at: transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2019.

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Hoy-Ellis CP, Goldsen J, Emlet CA, Hooyman NR. Creating a vision for the future: key competencies and strategies for culturally competent practice with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) older adults in the health and human services. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:80–107.

- Katz-Wise SL, Reisner SL, White Hughto JM, Budge SL. Self-reported changes in attractions and social determinants of mental health in transgender adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46:1425–1439.

- Olson KR, Durwood L, DeMeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities [published correction appears in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2018;142:2015–3223.

- Streed CG, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:256–267.

- Muralidharan S, Acharya A, Koshy AV, Koshy JA, Yogesh TL, Khire B. Dentition status and treatment needs and its correlation with oral health-related quality of life among men having sex with men and transgenders in Pune city: a cross-sectional study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2018;22:443.

- Greene MZ, France K, Kreider EF, et al. Comparing medical, dental, and nursing students’ preparedness to address lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer health. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0204104.

- Noonan EJ, Sawning S, Combs R, et al. Engaging the transgender community to improve medical education and prioritize healthcare initiatives. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30:119–132.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2020;18(1):40–43.

CREATING A TRANSFRIENDLY OFFICE ENVIRONMENT

CREATING A TRANSFRIENDLY OFFICE ENVIRONMENT CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

This is a great article! I have in the past 6 months came across a lot of gender sensitive situations, women transitioning into men, vice versa, and at the end of the day I never want to offend anyone.