KHOSRORK/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

KHOSRORK/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Basic Prevention and Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders

While at increased risk for these injuries, dental hygienists can implement strategies for effective prevention and care to ensure the longevity of their careers.

Authors’ note: This information is not intended to aid in self-diagnosing any type of injury or condition. It is for educational purposes only.

About 96% of dental hygienists experience a musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) at some point in their careers.1 While the severity and duration may vary, the ability to recognize the onset of a MSD and address early symptomology can help limit the possibility of developing a long-term, chronic condition. Although routine dental hygiene practice is associated with repetitive and sustained activities, evidence suggests that ergonomic equipment, optimal positioning, and corrective movements may alleviate the onset of a MSD.2–5

Sprains, strains, tendinitis, nerve irritation, joint inflammation, and muscle spasms are all MSDs. Because typical dental hygiene practice often involves prolonged bouts of sitting, looking downward, grasping instruments, and using a computer, the focus of this article is on MSDs in body regions most commonly impacted: thoracic spine (mid-back), cervical spine (neck), shoulder/scapula, elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand.

Cervical/Thoracic Strain

The full human spine has a unique orientation, as each of its four regions has a curve of its own distinct shape. As a result of the ongoing need to look downward during patient care (Figure 1, page 26), a dental hygienist is often required to slouch forward, which strains the thoracic and cervical spines. This causes the respective curves in these areas (kyphosis in the thoracic spine and lordosis in the cervical spine) to be exaggerated, placing additional stress on the spine. Signs and symptoms of cervical/thoracic strain are pain, muscle spasms, swelling, and stiffness.6

Rotator Cuff Strain

The body has a group of four small muscles: teres minor, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and subscapularis. Together, these are referred to as the “rotator cuff,” which stabilizes the shoulder joint, particularly during dynamic movements where the upper arm is maneuvered away from the chest (Figure 2). When using hand instruments, a dental hygienist’s arm may be maintained in a position where the elbow is bent and held away from the upper body for extended periods; this can overexert the rotator cuff musculature, causing it to fatigue, cramp, or spasm.6

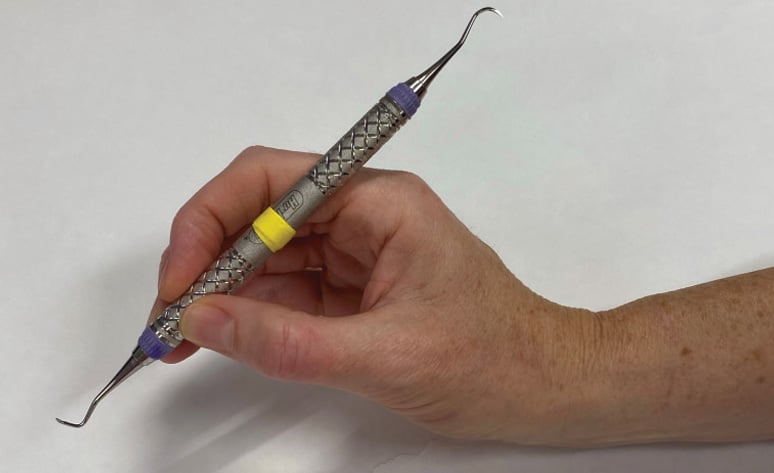

Lateral Epicondylalgia

The muscles on the posterior forearm, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor carpi ulnaris, and extensor digitorum help to extend the wrist and fingers. They are especially useful when performing a sustained grasp (Figure 3), and moving the wrist to maneuver an object (such as while taking a working stroke during calculus removal). This injury, commonly known as “tennis elbow,” typically manifests as localized pain over the attachment site where this group of muscles originates near the lateral aspect of the elbow through a shared tendon, and is characteristically most symptomatic during pinching and gripping activities with the elbow relatively extended. Additional symptoms include pain, burning, or an ache localized to the outside of the elbow.6

De Quervain Tenosynovitis

The muscles that move the thumb into abduction and extension (out and away) from the palm have long tendons that bisect the wrist and thumb joints (Figure 4). These tendons—those of abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, and extensor pollicis longus—create a triangular-shaped space called the “anatomical snuffbox” on the lateral aspect of the thumb near its base. During sustained pinching activities, as would occur when grasping and activating a working stroke, these tendons can be taxed to a point where inflammation forms, creating localized discomfort where the lateral thumb meets the wrist. Other symptoms may be swelling near the base of the thumb, difficulty moving the thumb and wrist when doing something that involves grasping or pinching, or a “sticking” sensation in the thumb when moving it.6

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

The carpal tunnel is a narrow, circular space on the anterior wrist; this small opening contains nine tendons and one nerve. The physical space of the carpal tunnel is widest with the wrist in a neutral or straight position (Figure 5). Whenever the wrist is held in a flexed or extended position for a long time, as when scaling difficult-to-reach areas of the mouth or using a standard computer mouse, the nerve contained with the carpal tunnel can be pinched or occluded, causing intermittent or constant symptoms of tingling or numbness in the tips of the thumb, index, middle and ring fingers.6

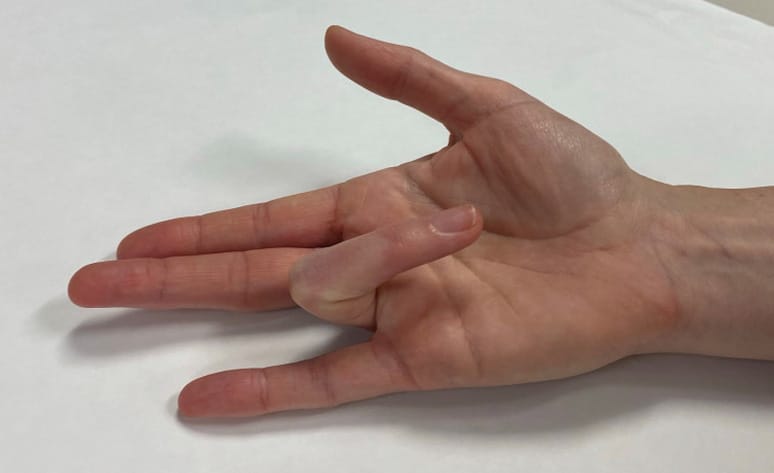

Trigger Finger

The muscles that help provide a power grip in the hand are primarily embedded in the anterior forearm. They traverse distally toward the hand via long tendons, and several small ligaments run perpendicular to the tendons in order to anchor them. These anchors, called “pulleys,” can become irritated and inflamed during sustained, forceful grasping or pinching, such as while holding an instrument. When the fingers are brought down toward the palm, as in making a customary fist, this localized inflammation can cause one or more fingers to remain struck in a locked-down position (Figure 6). In more severe cases, the finger cannot be actively extended and the unaffected hand must manually release the finger back to fully open the hand.

First Carpometacarpal Osteoarthritis

As the body ages, the joints degrade, causing the cartilage that lines the two bony ends to wear and create a “bone-on-bone” effect. The first carpometacarpal (CMC) joint at the base of the thumb as it meets the wrist is often the first to experience this wear (Figure 7). In order to engage the thumb musculature optimally and avoid unnecessary stress on adjacent joints, the tip joint (interphalangeal) and middle joint (metacarpophalangeal) of the thumb should be slightly bent; performing repetitive or sustained pinching with the thumb straight or collapsed through these joints causes biomechanical stress to be transferred down to the CMC joint. Unmanaged trauma on this basal joint of the thumb can lead to additional stress and premature degradation, causing a visible deformity and, eventually, pain with most types of pinching.

Based on current evidence, four strategies are able to limit the onset and severity of an MSD: loupes, equipment, microbreaks, and movement.

Loupes

The use of loupes can help to preserve the optimal position of the cervical and thoracic spines while also positively influencing the orientation of the shoulder blades, which articulate directly with the shoulders. Loupes can be customized based on the clinician’s vision, and may include a light for improved visualization during use. While the cost of loupes is considerable, avoiding the expenses associated with care and management of a work-related MSD justifies the cost.

Equipment

Ergonomic equipment designed to reduce MSD risk is widely available. Examples include: power instrumentation in conjunction with hand instrumentation; instruments with wide-diameter handles instead of narrow ones; split keyboard and vertical mouse instead of standard ones; high-low patient table to enable the dental hygienist to assume a standing position; and saddle chair when seated to promote proper alignment of the spine.

Microbreaks

Dental hygienists must take consistent, frequent breaks from repetitive and sustained activities. Clinicians who treat one patient every hour time are able to interrupt stress by properly repositioning the body. Evidence suggests that breaks as short as 30 seconds every hour might reduce the onset of an MSD.7,8

Movement

Customary hygiene practice requires the body to be compromised from its ideal alignment and biomechanical advantage at times. Therefore, performing corrective movements may help offset the effects of taxing activities. Recently, the Core Four model has been proposed as an efficient, focused, and simple paradigm for restoring alignment and promoting tissue health.5 This model involves two stretches and two exercises, can be completed in 5 minutes or less, and based on our knowledge, is the first specific, corrective movement model to be formally introduced for oral health providers. The article “Ergonomics Reinvigorated” in the January 2019 issue of Dimensions of Dental Hygiene provides more information on this technique.

Conclusion

MSDs are incredibly common among dental hygienists. This is why prevention is crucial for the longevity of a dental hygienist’s career. For anyone who may be experiencing an MSD, seeking personalized care from a qualified healthcare professional is essential if symptoms do not improve within 72 hours following their onset. This may include a consultation from a physical therapist, occupational therapist, chiropractor, licensed massage therapist, or primary care provider. Without early intervention and a consistent preventive routine, a minor MSD can become debilitating and potentially decrease a dental hygienist’s ability to continue working effectively.

References

- Hayes MJ, Smith DR, Cockrell D, et al. An international review of musculoskeletal disorders in the dental hygiene profession. Int Dent J. 2010;60:343–352.

- Michalak-Turcotte C. Controlling dental hygiene work-related musculoskeletal disorders: the ergonomic processJ J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:41–48.

- Plessas A, Bernardes Delgago M. The role of ergonomic saddle seats and magnificent loupes in the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Dent Hygiene. 2018;16:430-440.

- Hayes MJ, Taylor JA, Smith DR. Predictors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hygiene. 2012;10:265–269.

- Wilkinson BJ, Bell K, Coplen A. Ergonomics reinvigorated. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2019;17(1):36–39.

- Skirven TM, Osterman AL, Fedorczyk J, Amadio PC. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby; 2011.

- McLean L, Tingley M, Scott RN, Rickards J. Computer terminal work and the benefits of microbreaks. Appl Ergon. 2001;32:225–237.

- De Sio S, Traversini V, Rinaldo F, et al. Ergonomic risk and preventive measures of musculoskeletal disorders in the dentistry environment: an umbrella review. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4154.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2022;20(1):24, 26-27.