STUDIO22COMUA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

STUDIO22COMUA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Addressing Childhood Obesity in the Dental Setting

Oral health professionals are in a unique position to provide screening and education based on individual risk factors to manage this public health issue.

This course was published in the June 2019 issue and expires June 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define obesity and identify its prevalence among American children and adolescents.

- Discuss the causes of obesity among children and adolescents.

- Explain the relationship between obesity and oral health and note possible interventions.

Childhood obesity is one of the most significant public health challenges of the 21st century, both in the United States and globally.1,2 Childhood obesity is a multifactorial disease with risk factors related to genetics, development, and the environment.3 Obese children are more likely to become obese adults, and are at risk for developing additional chronic medical conditions such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.4–6 Childhood obesity is also related to depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and social problems such as bullying.5 The persistence of these comorbid conditions into adulthood is not only costly to personal health, it presents an economic burden on society as well.6 With one in three children in the US overweight or obese, early identification and intervention are critical.4 Oral health professionals are well suited to promote healthy weight with patients and parents.

DEFINING OBESITY

Obesity is defined as an excess of body fat.7 The most common methods to measure body fat in the clinical environment are body mass index (BMI), skin-fold thickness, and waist circumference.7 BMI is not a direct measure of body fat, but an alternative measure reflecting weight as related to height (weight/height²).8 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers the calculation of BMI sufficient for screening purposes, as it is easy and inexpensive.9 More accurate direct measurements include bioelectric impedance analysis, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, densitometry, hydrometry, and magnetic resonance imaging.8 The CDC defines obesity in children and young people (ages 2 to 20) as having a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for children and young people of the same age and sex.10 This use of an age- and sex-specific percentile differs from calculating BMI for adults, and is necessary for children and teens as body composition varies with age and gender.7,10 Some argue that BMI use potentially exaggerates obesity in muscular children, as it does not distinguish fat from fat-free mass (muscle and bone,) or account for differing maturation patterns between ethnic groups.7

PREVALENCE AND TRENDS

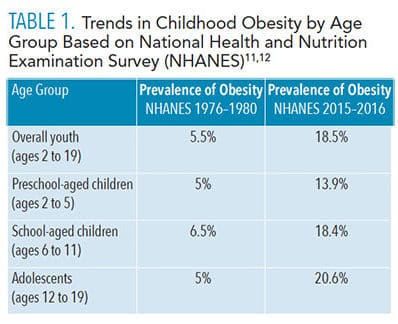

According to the most recent data from the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), prevalence of obesity among youth ages 2 to 19 in the US was 18.5%, representing a significantly increasing trend.11 These rates have tripled since the 1976–1980 NHANES results of 5.5%.12 Table 1 compares results of the NHANES conducted in 1976-1980 and 2015-2016.11,12

According to the 2015-2016 NHANES, obesity rates differ significantly by race and ethnicity. Obesity rates were found to be higher among Latino and Black children as compared to White and Asian children, with Latino boys and Black girls most likely to have obesity. In general, boys are slightly more likely to have obesity than girls.12 On a global level, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that from 1990 to 2016, the number of overweight or obese children younger than 5 increased from 32 million to 41 million, with the estimate that this number will grow to 70 million by 2025.2

CAUSES OF OBESITY

The most common cause of childhood obesity is the consumption of more calories from foods and beverages than a child or young person expends, known as a positive energy balance, in combination with being genetically predisposed to weight gain.4,5,7 Though genetic predisposition is a factor, it is not the single cause of obesity in most children.4 The majority of cases of childhood obesity are the result of the interaction of multiple modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors, including: genetics; endocrine (hormonal); nutrition: portion sizes and consumption of fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs); lack of physical activity (energy imbalance): high levels of television viewing/screen time; social and environmental factors; sleep duration and quality; race/ethnicity; socioeconomic status; and psychosocial, cultural, and community (neighborhood design and safety) factors.3,5,6,13

The most common cause of childhood obesity is the consumption of more calories from foods and beverages than a child or young person expends, known as a positive energy balance, in combination with being genetically predisposed to weight gain.4,5,7 Though genetic predisposition is a factor, it is not the single cause of obesity in most children.4 The majority of cases of childhood obesity are the result of the interaction of multiple modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors, including: genetics; endocrine (hormonal); nutrition: portion sizes and consumption of fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs); lack of physical activity (energy imbalance): high levels of television viewing/screen time; social and environmental factors; sleep duration and quality; race/ethnicity; socioeconomic status; and psychosocial, cultural, and community (neighborhood design and safety) factors.3,5,6,13

In addition to familial and societal influence, evolution plays an important part in shaping the food preferences of children. Humans are biologically designed to prefer sweet and salty foods and avoid bitter tastes.3 These preferences that once served as a means to help detect energy-rich foods and avoid poisons are now a risk factor for obesity. They persist into adolescence, leaving children and young adults especially vulnerable to poor food choices. Flavor and food preferences can be modified early in life, though children must be repeatedly exposed to certain foods to learn to like them.3 Unfortunately, research statistics reveal the following:3

- Beginning at age 2, children are more likely to eat a manufactured sweet than a fruit or vegetable.

- By the age of 4, 99% of children exceed the recommended sugar intake, while 92% do not eat the minimum recommended amount of vegetables.

- On any given day, 20% to 35% of children age 6 months and older do not eat fruit, and 30% to 40% of children do not eat vegetables.

- Sweets and sweetened beverages make up more than one-third of the increase in calories from the ages of 6 months to 4 years.

- The odds of consuming SSBs at age 6 is nearly doubled if they are consumed in infancy.

OBESITY AND ORAL HEALTH

Many studies have attempted to find a correlation between obesity and dental caries prevalence, with a focus on the consumption of SSBs or sugar-containing beverages (SCBs) by adolescents and adults. SCBs include SSBs and other beverages such as 100% fruit juice, which contains naturally occurring glucose and fructose.14 Findings specific to childhood obesity include a positive association between SCBs and the accumulation of fat in the lower torso around the abdominal area (central adiposity) and a direct association between dental caries and obesity.15–20

Other studies have noted an increased risk of dental caries in obese children but do not identify a causative relationship between the two, suggesting that common risk factors are most likely the result for their coexistence.18,19 In general, consumption of SSBs/SCBs and other foods high in sugar are risk factors for obesity as well as caries.

The association between childhood obesity and periodontal diseases has also been investigated, with results demonstrating a positive correlation between them.21 In addition to these evidentiary relationships, dental professionals must also consider the impact of the oral health effects of potential sequelae from comorbidities such as diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea.22

INTERVENTIONS IN THE DENTAL SETTING

While multiple factors contribute to chronic diseases of obesity and dental caries, both have dietary components with a key risk factor being the consumption of SSBs/SCBs.14,23 The majority of children and adolescents in the US consume 270 calories/68 g of sugar from SSBs on a daily basis, exceeding the daily intake recommended by both the American Heart Association (25 g) and WHO (less than 5% to 10% of total energy intake, equivalent to 25 g to 50 g).24,25

Due to the nature of the dental setting, oral health professionals are in a unique position to identify children at risk for both diseases, promote healthy food choices, and provide referrals to specialists. It has become increasingly important to become part of the interprofessional team that includes physicians, midlevel practitioners, registered dietitians, and public health officials to address this issue. Table 2 lists resources to obtain more information on steps oral health professionals can take to address obesity in their practice.

Significant research has been done on the attitudes and beliefs held by oral health professionals about their role in providing screening for obesity and nutritional/lifestyle counseling. This research suggests 30% to 50% of oral health professionals express discomfort with addressing adult or childhood obesity in the clinical setting for reasons such as: belief that obesity is not directly related to oral health, fear of appearing judgmental or offending parent/rejection, time constraints, lack of training in weight loss counseling, feeling unqualified to provide noncaries-related nutritional counseling, lack of patient interest/willingness, dental hygienists’ need for approval/support from the dentist(s), weight seen as a medical rather than a dental issue, and lack of reimbursement for services (screening/nutritional counseling).26–28 Other barriers include a lack of curriculum content addressing childhood obesity and nutritional intervention in dental and dental hygiene programs, and parental perception of healthy weight.26–29 More than 50% of parents of overweight/obese children underestimate their child’s weight.30

However, research has also provided some hopeful data in the form of positive parental/caregiver attitudes toward weight screening and nutritional counseling in the dental setting. Not only did 95% of caregivers feel the dental office was an appropriate place to receive information on exercise and healthy eating habits, they also believed a dental hygienist was an appropriate person to discuss healthy weight goals with parents.26

The results of a pilot project employing a “healthy weight intervention (HWI)” protocol used by dental hygienists in a pediatric dental setting demonstrated positive results.31 The protocol implemented motivational interviewing, which is based on individuals setting behavioral goals they believe they can attain.31 The HWI provided health report cards with health behavior modifications based on risk assessment information gathered by dental hygienists (nutrition, BMI, physical activity, etc).31 From this report card, the child selected a goal to work on over the next 6 months, and children with a BMI > 85% were given a medical referral. The authors reported the HWI was well-accepted by dental hygienists and caregivers, with nearly all caregivers instituting dietary changes to help their children meet their goals.31

ROLE OF ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Based on policies from the American Dental Association, American Dental Hygienists’ Association, and American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, nutrition counseling on healthy eating to reduce risk for caries and overall health is a component of prevention services to be provided during dental care.30 The overall role is to support healthy behaviors rather than a focus on weight loss. Weight loss is not always appropriate in children, as it could impair growth, so oral health professionals should focus on modifiable risk factors and support healthy behaviors, including:32

- Nutrition education of caregivers and children

- Reduce sources of added sugars in food and in beverages to aid in reducing caries risk and weight gain

- Follow the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines on juice consumption which suggest the following limits:14,33

— Ages 1 to 3: 4 oz daily

— Ages 4 to 6 years: 4 oz to 6 oz daily

— Ages 7 to 18: 8 oz or 1 cup daily

- Consume a diet high in fruits and vegetables

- Choose whole grains

- Focus on lean protein and lowfat milk

- Be active for at least 1 hour per day

- Referral to a primary care provider and/or registered dietitian when appropriate (if BMI screening indicates overweight/obese or the oral health professional believes there are concerns beyond their scope of practice)

Approaches to making healthy diet choices are available at: choosemyplate.gov.32 Resources are available in English and Spanish and include games, activity sheets, videos, and resources for parents. In dental offices with television screens or other electronic devices, the videos could be played during the child’s appointment. Resources could be posted to websites hosted by dental offices or printed and provided to children while waiting for their appointment. Other resources for parents include recipes; cookbooks; snack tips; and recommendations to cut back on sweets, make better beverage choices, and more. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics also has free resources, such as videos, recipes for kids, and tips available to help parents make good choices, to support a healthy weight at: eatright.org/for-kids.

CONCLUSION

Childhood obesity is a significant health concern, and oral health professionals are in a unique position to provide screening and education based on individual risk factors. On a clinical level, programs, such as the HWI, could be implemented and tailored to a specific practice or population. If dental professionals are unable to move beyond perceived barriers, many of the other tools presented could be presented as an educational handout. Taking small steps to include nutritional counseling in settings that are not already doing so may improve clinician comfort with the subject and open doors to more specific intervention practices in the future. At the very least, clinicians should educate their patients about current dietary guidelines, particularly those related to sugar intake.

Research has demonstrated the need for more specific education and training for both dentists and dental hygienists in the area of childhood obesity and intervention.16,23 Oral health professionals need to become part of an interprofessional approach to this health crisis, taking action not only on the clinical but community level.22,25 For example, oral health professionals may serve on multidisciplinary teams working with community stakeholders to improve access to healthier foods choices in schools, remove SSBs from school meals and events, and create early intervention programs or institute wellness programs. Additionally, oral health professionals can act as advocates and influence public policy on a local, national, or global level by working toward professional curriculum changes; supporting legislative changes to reduce consumption of SSBs (taxation, labeling, portion size, or advertising); or advocating for regulations to improve food equity and access to clean drinking water.

REFERENCES

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood Obesity Facts: Overweight and Obesity. Available at: cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Facts and Figures on Childhood Obesity. Available at: who.int/end-childhood-obesity/facts/en/. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- National Academies of Sciences, Medicine. Obesity in the Early Childhood Years: State of the Science and Implementation of Promising Solutions: Workshop Summary. Available at: nap.edu/catalog/23445/obesity-in-the-early-childhood-years-state-of-the-science. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Kumar S, Kelly AS. Review of childhood obesity: From epidemiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:251–265.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Causes and Consequences of Childhood Obesity. Available at: cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/causes.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Vargas CM, Stines EM, Granado HS. Health-equity issues related to childhood obesity: A scoping review. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S32–S42.

- Sahoo K, Sahoo B, Choudhury AK, Sofi NY, Kumar R, Bhadoria AS. Childhood obesity: Causes and consequences. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2015;4:187–192.

- Wells JCK, Fewtrell MS. Measuring body composition. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:612–617.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: About Child & Teen BMI Healthy Weight . Available at: cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Childhood Obesity: Overweight and Obesity. Available at: cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NCHS Fact Sheets. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet_nhanes.htm. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- The State of Obesity. Childhood Obesity Trends. Available at: stateofobesity.org/childhood-obesity-trends/. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Chi DL, Luu M, Chu F. A scoping review of epidemiologic risk factors for pediatric obesity: Implications for future childhood obesity and dental caries prevention research. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S8–S31.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Dietary Recommendations for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Available at: aapd.org/research/oral-health-policies–recommendations/dietary-recommendations-for-infants-children-and-adolescents/. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Frantsve-Hawley J, Bader JD, Welsh JA, Wright JT. A systematic review of the association between consumption of sugar-containing beverages and excess weight gain among children under age 12. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S43–S66.

- Costacurta M, DiRenzo L, Sicuro L, Gratteri S, De Lorenzo A, Docimo R. Dental caries and childhood obesity: Analysis of food intakes, lifestyle. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:343–348.

- Alm A, Fåhraeus C, Wendt LK, Koch G, Andersson-Gäre B, Birkhed D. Body adiposity status in teenagers and snacking habits in early childhood in relation to approximal caries at 15 years of age. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:189–196.

- Hayden C, Bowler JO, Chambers S, et al. Obesity and dental caries in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:289–308.

- Garcia RI, Kleinman D, Holt K, et al. Healthy futures: engaging the oral health community in childhood obesity prevention—conference summary and recommendations. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S136–S140.

- Hilgers KK, Akridge M, Scheetz JP, Kinane DF. Childhood obesity and dental development. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:18–22.

- Martens L, De Smet S, Yusof MYPM, Rajasekharan S. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontal disease in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2017;18:69–82.

- Narang I, Mathew JL. Childhood obesity and obstructive sleep apnea. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:134202.

- Tinanoff N, Holt K. Introduction to proceedings of healthy futures: engaging the oral health community in childhood obesity prevention national conference. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S5–S7.

- American Heart Association. Sugar Recommendation Healthy Kids and Teens Infographic. Availalbe at: heart.org./en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/sugar-recommendation-healthy-kids-and-teens-infographic. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet. Available at: who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Cole DDM, Boyd LD, Vineyard J, Giblin-Scanlon LJ. Childhood obesity: dental hygienists’ beliefs attitudes and barriers to patient education. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:38-49.

- Greenberg BL, Glick M, Tavares M. Addressing obesity in the dental setting: What can be learned from oral health care professionals’ efforts to screen for medical conditions. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S67–S78.

- Wright R, Casamassimo PS. Assessing attitudes and actions of pediatric dentists toward childhood obesity and sugar-sweetened beverages. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S79–S87.

- Divaris K, Bhaskar V, McGraw KA. Pediatric obesity-related curricular content and training in dental schools and dental hygiene programs: systematic review and recommendations. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:S96–S103.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Policy Manual. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7614_Policy_Manual.pdf. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Tavares M, Chomitz V. A healthy weight intervention for children in a dental setting: a pilot study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:313–316.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Choose MyPlate: Become a MyPlate Champion. Available at: choosemyplate.gov/kids-become-myplate-champion. Accessed May 21, 2019.

- Heyman MB, Abrams SA. Fruit juice in infants, children, and adolescents: current recommendations. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20170967.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2019;17(6):44–47.

Great reminder for all us clinician to look beyond the mouth to help our patients.