PETOEI / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

PETOEI / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

Reducing the Use of Hospital Emergency Departments for Dental Care

New strategies are needed to ensure vulnerable children receive preventive and routine oral health care services.

Dental professionals are well aware of the interconnectedness of oral and overall health. Strategies have been implemented to improve the oral health of children in the United States—from the provision of preventive dental care by dental hygienists in school-based settings to including pediatric dental services in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Unfortunately, the oral health of the nation’s most vulnerable children remains in jeopardy. Access to professional dental care is the cornerstone of improving and maintaining oral health among all populations. One indicator of how easily dental care can be obtained is to look at the number of people who visit hospital emergency departments (ED) for the treatment of dental problems. The Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) contains information from approximately 30 million hospital ED discharges.1 In 2014, my colleagues and I published a study in Pediatric Dentistry that utilized the NEDS database to identify the characteristics of children who visited EDs to receive treatment for dental conditions.2 Results showed that 215,073 children visited the ED for treatment of dental problems in 2008. This group comprised more than 91,000 children covered by Medicaid and 68,000 children without insurance.2 Of those children who sought dental care in EDs, 72% were from families with mean household incomes of $49,000 or less. Members of these households tend to have less education and low oral health literacy compared to families whose mean income is higher.3

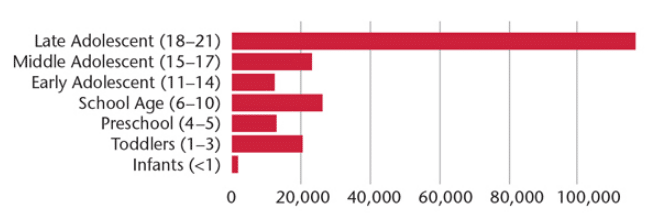

Study results also showed that late adolescents (age 18 to 21) were the most likely to visit EDs for dental treatment (Figure 1). Late adolescents are often without parental supervision; more than 50% of individuals age 18 to 23 live independently.4 Karimi et al5 found that 18- to 24-year-olds have the lowest health care utilization among adults. Moreover, many in this age group have limited financial means, little credit history, and may face challenges in acquiring funding for health care expenses.6 Additionally, Wolf et al7 showed that late adolescents may not have good oral health literacy, which is critical for developing and maintaining effective health practices.

There are two primary reasons why children visit the ED with a dental problem. First, the pain has become so severe that emergency treatment is necessary. Second, the child does not have regular access to dental care, which may be due to a lack of insurance/funding, absence of a dental care provider with appointment availability in the patient’s geographic area, or lack of transportation to get to dental appointments. Most of the ED visits for dental treatment were necessitated by untreated dental caries, pulpal and periapical disease, gingival and periodontal diseases, and mouth cellulitis—all of which are preventable.

This article examines why the use of hospital EDs for dental treatment is ineffective; the status of implemented strategies to increase access to care; and suggestions for more effective ways to ensure children receive necessary oral health care services.

RESULTS OF EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CARE

Perhaps the most obvious reason that EDs should not be a source for dental treatment is cost. The overall charges for the ED visits analyzed in our study were $104.2 million, and the average hospital charge was $564 per visit.2 A typical preventive dental office visit ranges from $50 to $350, depending on region. Plus, the use of EDs does not eliminate the need to see a dental professional. A study by Cohen et al8 showed that 96% of patients who visited the ED for a dental problem still needed follow-up care from a dentist. This demonstrates that the ED visit doesn’t typically serve as an alternative to visiting the dental office, but rather increases the overall costs of care. Another important finding to consider is what happens after the ED visit. While 95% of the 215,073 ED visits resulted in routine discharge, 8,723 patients were admitted to long- or short-term care facilities or enrolled in home health care.2 In other words, these ED visits were further dispersed into the health care system, continuing to grow the charges associated with additional care. In fact, the 7,195 ED visits that resulted in hospitalizations had a 4.6 day mean length of stay and incurred $162 million in hospital charges—55.5% more than the hospital charges for all of the 215,073 ED visits.2 Perhaps the most important part of this data analyzation is to identify the characteristics of the 7,195 patients who were hospitalized in order to facilitate early identification of dental problems with the goal of preventing the need for ED visits and hospitalizations.

Another concern is the quality of care provided in EDs. Only 1.8% of US dentists practice in hospitals9 and research shows that hospital EDs poorly manage dental problems.10 For example, a study by Al-Khabbaz et al11 found that physician knowledge of oral health was low.

IMPACT OF IMPLEMENTED STRATEGIES

It was hoped that the ACA would improve children’s access to professional dental care. Theoretically, the ACA ensures coverage for pediatric dental services; however, it does not require individuals to purchase insurance, and many have declined coverage.12,13 For instance, households whose mean income is $49,000 or less are more likely to decline coverage under the ACA than those with higher incomes. This supports the theory presented in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which suggests that individuals whose low-level needs are not being met will not consider high-level matters important.14 For example, if individuals are concerned about their personal safety because they’re living in a dangerous neighborhood, they are not likely to view pediatric dental visits as important. Additionally, implementation of the ACA varies from state to state. For example, Utah’s ACA covers only prevention services and not general or restorative dental care.12

The expansion of Medicaid was also thought to improve access to care for vulnerable populations. And current American Dental Association (ADA) data show that children covered by Medicaid who visited the dentist during a 1-year period rose from 29% in 2000 to 48% in 2013.15 Although this improvement is significant, 48% is still a low level of utilization. The results of our 2008 study found that while Medicaid did not insure every child for routine and emergency dental care, it was the largest payor for patients who sought dental treatment in EDs.2 Additional ADA data suggest that the Medicaid share of dental ED visits has actually increased.16 In fact, another study demonstrates that the number of ED visits for dental care is trending upward, not downward.17

FIXING THE PROBLEM

The dental profession needs to develop strategies to keep children out of hospital EDs and get them into dental homes. A major challenge is the fact that 58% of dentists in the US still practice in the traditional solo private practice.18 While patients may value their personal relationship with their family dentist, this structure doesn’t help expand access to care. For example, large group practices can offer weekend and after-hours appointments that may improve utilization by at-risk populations. These expanded hours would be difficult for a solo practitioner to provide.

Increasing collaboration between oral health care providers to facilitate 24-hour emergency dental care for children would effectively solve this problem, but it seems difficult to imagine how this could be accomplished. A more practical alternative is integrate dental hygienists into the medical practice where they can provide valuable preventive treatments such as the application of fluoride varnish and placement of dental sealants, while also providing critical oral health education to parents/caregivers.19 Also, broadening the ability of dental hygienists to provide care directly to patients outside of the traditional dental practice and the growth of expanded-function mid-level practitioners could help alleviate access-to-care problems. Today, 38 states enable dental hygienists to provide care directly to patients and 16 states allow dental hygienists to receive payment for services directly from Medicaid.20,21 The ADA, however, has historically opposed such efforts.22–24

Evaluation of the insurance status associated with ED visits and hospitalizations due to dental conditions among children revealed some important patterns. Patients covered by Medicaid comprised 43% of the ED visits for dental treatment and 50% of the hospitalizations.2 These data suggest that providing oral health education and preventive care to children covered by Medicaid is critical to improving oral health outcomes.

Analysis of NEDS data from 2008 showed that of the children visiting the ED for dental treatment, 96% did not have other health problems.2 Among those patients who were hospitalized, 15% had one co-morbid condition, 4% had two, and 1% had three or more.2 Clearly, providing specialized care for dental-related ED visits to those with preexisting health conditions could help reduce hospitalizations and health care resource utilization. Alternatively, additional or mandated dental Medicaid support for children with comorbidities may help prevent these patients from visiting EDs for dental problems. Patients with comorbidities may also be more likely to visit physicians for medical care, which supports the concept of integrating dental hygienists into medical practices.

CONCLUSION

Several factors increase the use of EDs for treatment of dental problems in children, including coverage by Medicaid, the presence of comorbidities, age between 18 and 21, and mean household income of $49,000 or less. Children meeting three or four of these criteria should be given special care in preventive dental services and receive more aggressive, customized care if they present to the ED in an attempt to prevent hospitalization.

Additional strategies must be sought and implemented to ensure that vulnerable children have access to oral health care services provided by professional dental health care providers. Otherwise, hospital EDs will continue to be used for dental treatment, children and parents/caregivers will experience more lost days from school and work, and children will go on to experience significant health problems caused by preventable dental diseases.

References

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. About the NEDS. Available at: hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp#about. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Allareddy V, Nalliah RP, Haque M, Johnson H, Rampa SB, Lee MK. Hospital-based emergency department visits with dental conditions among children in the United States: nationwide epidemiological data. Pediatr Dent. 2014;36:393–399.

- Naghibi Sistani MM, Yazdani R, Virtanen J, Pakdaman A, Murtomaa H. Determinants of oral health: does oral health literacy matter? ISRN Dent. 2013;2013:249591.

- Jones JM. In US, 14% of Those Aged 24 to 24 Are Living With Parents. Available at: gallup.com/poll/167426/aged-living-parents.aspx. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Karimi S, Keyvanara M, Hosseini M, Jazi MJ, Khorasani E. The relationship between health literacy with health status and healthcare utilization in 18-64 years old people in Isfahan. J Educ Health Promot. 2014;3:75.

- Advisor Perspectives. Median Household Incomes by Age Bracket: 1967–2014. Available at: advisorperspectives.com/dshort/updates/Household-Incomes-by-Age-Brackets.php. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Wolf MS, Wilson EA, Rapp DN, et al. Literacy and learning in health care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S275–8114.

- Cohen LA, Bonito AJ, Eicheldinger C, et al. Comparison of patient centeredness of visits to emergency departments, physicians, and dentists for dental problems and injuries. J Am Coll Dent. 2010;77:49–58.

- Strauss E. The salary of hospital dentists. Global Post. Available at: everydaylife.globalpost.com/salary-hospital-dentists-33333.html. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Tulip DE, Palmer NO. A retrospective investigation of the clinical management of patients attending an out of hours dental clinic in Merseyside under the new NHS dental contract. Br Dent J. 2008;205:659–664.

- Al-Khabbaz AK, Al-Shammari KF, Al-Saleh NA. Knowledge about the association between periodontal diseases and diabetes mellitus: contrasting dentists and physicians. J Periodontol. 2011;82:360–366.

- American Dental Association. Affordable Care Act, Dental Benefits Examined. Available at: ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2013-archive/august/affordable-care-act-dental-benefits-examined. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Obamacare Facts. Dental Insurance. Available at: obamacarefacts.com/ dental-insurance/dental-insurance. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Green CA. A theory of human motivation. Available at: psychclassics. yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- American Dental Association. The Oral Health Care System: a State-by-State Analysis. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/ OralHealthCare-StateFacts/Oral-Health-Care-System-Key-Findings.ashx. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Wall T, Vujicic M. Emergency department use for dental conditions continues to increase. American Dental Association Research Briefs. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/ HPIBrief_0415_2.ashx. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Allareddy V, Rampa S, Lee MK, Allareddy V, Nalliah RP. Hospital-based emergency department visits involving dental conditions: profile and predictors of poor outcomes and resource utilization. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:331–337.

- American Dental Association. Dental Practice. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/10_sdpi.ashx. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Braun PA, Kahl S, Ellison MC, Ling S, Widmer-Racich K, Daley MF. Feasibility of colocating dental hygienists into medical practices. J Public Health Dent. 2013;73:187–194.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Medicaid Direct Reimbursement of Dental Hygienists. Available at: adha.org/reimbursement. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access States. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7513_Direct_Access_to_Care_from_DH.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- Levine D. Why Are Dentists Opposing Expanded Dental Care? Available at: governing.com/topics/health-human-services/gov-why-are-dentists-opposing-expanded-dental-care.html. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- American Dental Association. American Dental Association Statement on Accrediting Dental Therapy Education. Available at: ada.org/en/press-room/news-releases/2015-archive/august/american-dental-association-statement-on-accrediting-dental-therapy-education-programs. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- American Dental Association. Do Midlevel Providers Improve Oral Health? Available at: ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2013-archive/january/do-midlevel-providers-improve-oral-health. Accessed January 13, 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2016;14(02):20,22–24.