GAB13 / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

GAB13 / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

Treating Patients With CREST Syndrome

Dental hygienists are well prepared to help those with this autoimmune disorder maintain their oral health.

This course was published in the February 2016 issue and expires February 28, 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define CREST syndrome.

- Discuss what the research says about the etiology, characterizations, diagnosis, and treatment of this disease.

- Identify the treatment considerations for patients with CREST syndrome.

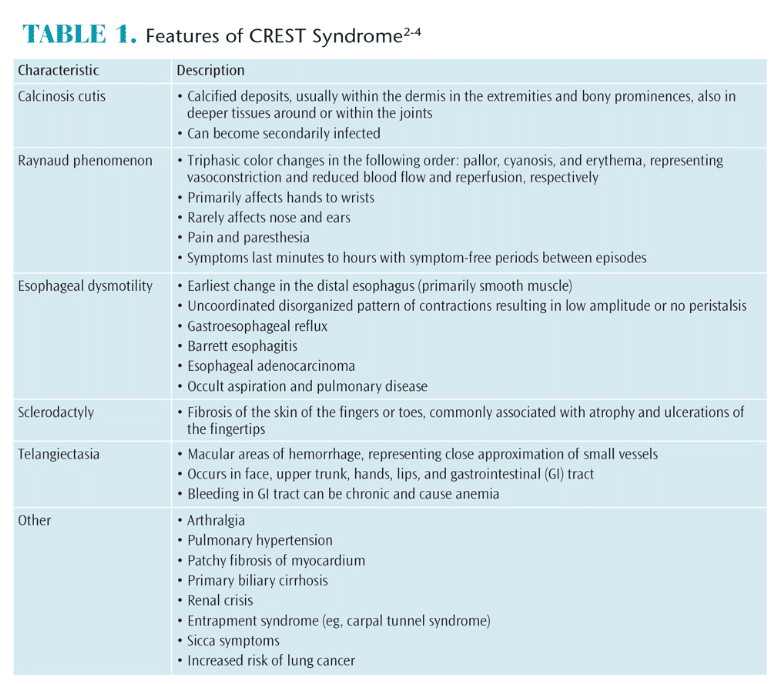

CREST syndrome is an autoimmune disorder that is a localized variant of systemic scleroderma, a chronic connective tissue disease.1,2 CREST is characterized by the combination of five autoimmune conditions: calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia (Table 1).1–4 A slowly progressing disease, CREST syndrome primarily affects middle-aged women and 55 is the mean age of onset.1,5 Approximately 21 new cases of CREST syndrome are diagnosed per 1 million adults in the United States.6 While there is no known definitive cause of CREST, some proposed etiological factors include genetics, exposure to environmental or infectious agents, and graft-vs-host reactions.7

CREST syndrome is diagnosed with a blood test and the presentation of three of the five aforementioned autoimmune conditions.3 Of the various types of scleroderma, only CREST tests positive for the anticentromere antibody Anti-Scl 70.4,8 Imaging studies used to aid in the diagnosis of the syndrome include plain film radiographs (vs digital radiographs), computed tomography, bone scanning, Doppler ultrasonography, radiologic barium studies, esophageal transit time with fluoroscopy, esophageal manometry, and transthoracic echocardiography. These modalities are useful for identifying the extent and progression of the disease.4 Making a differential diagnosis can be difficult because it mimics other conditions, such as mixed connective-tissue disease, amyloidosis, silica exposure, vinyl chloride disease, eosinophilic fasciitis, scleromyxedema, chronic graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic vasculitis, and reflex sympathetic dystrophy.4

Regardless of its etiology, CREST is a debilitating and incurable disease that affects the entire body. Survival rates decrease substantially from 78% at 5 years to 27% at 20 years.6 The hardening of tissues associated with calcinosis cutis affects the internal organs, leading to serious health complications such as restrictive lung disease, primary biliary cirrhosis of the liver, and vascular dementia.1–3,9,10 Renal involvement is associated with half of all scleroderma-related deaths in patients with significantly involved skin changes.4 In addition to systemic complications, the head and neck are susceptible to effects of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), vasoconstriction, fibrosis, hemorrhage, limited mouth opening (microstomia), increased incidence of periodontal diseases, and xerostomia.1,2 Because CREST manifests in orofacial signs and symptoms, dental hygienists are in a unique position to serve this patient population.

RESEARCH REVIEW

CREST syndrome is characterized by slow onset and variable presentation, making study of its epidemiological features difficult. Also, there is a lack of uniformity in diagnostic criteria. A systematic literature review found that in 50% of cases, Raynaud phenomenon was the first symptom that appeared, and, in many cases, years before diagnosis. Raynaud phenomenon, however, is also common in other connective tissue diseases, which may explain why some cases of CREST are misdiagnosed. A better diagnostic model for CREST is needed.11

To improve detection and follow-up of patients presenting with different manifestations of this syndrome, an interdisciplinary registry was founded. The registry reports the occurrence of different symptoms, age of onset, and the progression of the disease. In compiling these data, researchers hope to provide a large patient base from which to recruit participants for clinical studies. Additionally, there is hope that patients with CREST syndrome overlap and those in the earliest stages of the disease can be more readily identified.5

Treatment of CREST has been primarily focused on treating the symptoms associated with each of the five conditions. Fibrosis/calcinosis is irreversible, but the goal of current therapies is to slow disease progression. Medication therapies include D-penicillamine and cyclophosemide, with D-penicillamine showing the most promising results.2 Raynaud phenomenon can be treated with calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine; prazosin; prostaglandin derivatives such as prostaglandin E1; aspirin; and topical nitrates.2,12 The Cochrane Collaboration undertook a meta-analysis to determine the efficacy of prazosin for the treatment of Raynaud phenomenon.13 Prazosin was found to be more effective than a placebo, but the response to the medication was modest and side effects were common. GERD, as a symptom of CREST, is managed with antacids, H2 blockers, proton-pump inhibitors, prokinetic agents, consuming small meals, and laxatives.13 In extreme cases, patients with CREST might also benefit from physical therapy or surgery.2 Facial telangiectasia has been treated successfully with pulsed-dye laser treatment, while symptomatic gastrointestinal telangiectasia has been managed with estrogen-progesterone or desmopressin, laser ablation, or sclerotherapy.4

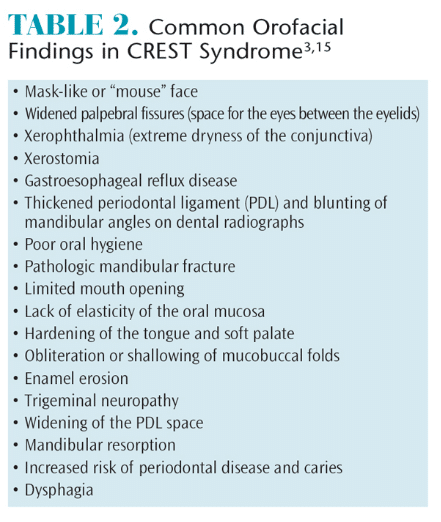

Little information about CREST is available in the dental/dental hygiene literature. A cross-sectional study of patients with CREST and reduction in gingivitis concluded that dental professionals must take manual dexterity into account when providing patient education.14 Available research focuses on the pathogenesis and treatment of CREST and includes oral manifestations.1,15 Currently, most pharmacological interventions are aimed at suppressing the immune system, dilating blood vessels, and increasing blood flow, in addition to treating individual organ problems. The most frequent oral finding to precede systemic involvement appears to be trigeminal neuropathy followed by enlargement of the periodontal ligament (PDL) space.15 These findings are significant for the dental hygienist who can refer patients to medical specialists based on oral signs and symptoms. A proactive approach is necessary to prevent dental disease due to an increased risk for oral pathologies in patients with the syndrome. CREST involves the entire orofacial complex, and a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to ensure patient needs are met.16

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

Due to the numerous vascular, inflammatory, and fibrotic changes associated with CREST, patients are more prone to oral disease. Table 2 provides a list of common orofacial findings in patients with the syndrome. Dental hygienists should be alert for signs and symptoms indicative of CREST, and refer patients to a rheumatology specialist for evaluation. Patients might present first with persistent GERD, resulting in acid erosion, dentinal hypersensitivity, and mucogingival paresthesia.2,16 Trigeminal neuropathy with no clinical cause is often an early sign of CREST.15 Due to fibrosis of the salivary glands, xerostomia, increased caries risk, and candida infections are common among these patients.17 Xerostomia combined with tongue rigidity, tissue atrophy, and bone resorption may make patients with CREST poor candidates for prosthodontics or implants.17

Due to the numerous vascular, inflammatory, and fibrotic changes associated with CREST, patients are more prone to oral disease. Table 2 provides a list of common orofacial findings in patients with the syndrome. Dental hygienists should be alert for signs and symptoms indicative of CREST, and refer patients to a rheumatology specialist for evaluation. Patients might present first with persistent GERD, resulting in acid erosion, dentinal hypersensitivity, and mucogingival paresthesia.2,16 Trigeminal neuropathy with no clinical cause is often an early sign of CREST.15 Due to fibrosis of the salivary glands, xerostomia, increased caries risk, and candida infections are common among these patients.17 Xerostomia combined with tongue rigidity, tissue atrophy, and bone resorption may make patients with CREST poor candidates for prosthodontics or implants.17

Radiographically, CREST might manifest with generalized widening of the PDL spaces, increased thickening of the lamina dura around posterior teeth, and bone resorption of the angle of the mandible.15,17 Bone resorption is thought to be a result of the pressure exerted by an increased tightening of the facial structures due to fibrosis in combination with hypovascularization, and often results in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain and dysfunction.15–17 In this instance, the clinician might note crepitus, popping, and clicking of the TMJ.17 These manifestations often affect the patient’s ability to chew and swallow effectively.16

The tightening of the skin around the hands and orofacial structures is particularly important to oral health professionals. This impacts the patient’s ability to perform oral self-care, movement of oral structures, and contributes to an increased risk of oral disease.15,18 Due to the loss of elasticity and subsequent microstomia, both self- and professional care can be challenging.15,18 Fibrotic changes in mucosal tissues cause them to appear thin, pale, and tight, and tissue hardening may also be evident in the tongue and soft palate.17 Mucosal fibrosis can also cause gingival recession and stripping of the attached gingiva.17 The lack of sufficient self-care, limited mouth opening, and decreased vascularization are implicated in an increased incidence and risk of periodontitis in patients with CREST.16

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

CREST syndrome has many complicating factors, and these patients are at high risk for dental caries, periodontal diseases, and gingivitis.19 There are practical ways, however, for dental hygienists to successfully treat this population. A 2-month or 3-month recare interval is essential to stabilize and maintain dental health.15,17 As more than 75% of patients with CREST on a calcium channel blocker regimen develop gingival hyperplasia, dental hygienists need to identify this side effect and refer patients to a periodontist for gingival reduction surgery.12,19,20 Recurrence of gingival hyperplasia is likely as long as patients remain on calcium channel blockers; hence, consultation with the prescribing physician to determine alternative medications should be considered.20 Additionally, regular, thorough oral cancer screenings are of increased importance due to the elevated risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and pharynx among patients with CREST.15,17

The complications of scleroderma lead to fibrosis and tightening of facial skin. This causes microstomia.14,21 Mouth stretching and oral augmentation exercises have been successful in increasing the opening of the oral cavity by 3 mm to 5 mm.17,18 Instructing patients in simple stretching exercises can increase flexibility of the face and mouth (Table 3).15,18

For the management of xerostomia, pharmaceutical agents, such as pilocarpine and evoxac, may help stimulate saliva flow.17 Xylitol-containing lozenges or mints and salivary substitutes may improve patient comfort.2,15,17

Caries prevention requires a combination of in-office and at-home fluoride treatments. Limited opening of the oral cavity may make the use of custom trays impossible.15 Fluoride varnish is easily applied with a small brush and can be placed at each recare visit.15,22 Fluoride gels can be brushed on the teeth with a child-size toothbrush and left overnight.15,22 Patients should avoid sugar consumption due to increased caries risk.2,15

Caries prevention requires a combination of in-office and at-home fluoride treatments. Limited opening of the oral cavity may make the use of custom trays impossible.15 Fluoride varnish is easily applied with a small brush and can be placed at each recare visit.15,22 Fluoride gels can be brushed on the teeth with a child-size toothbrush and left overnight.15,22 Patients should avoid sugar consumption due to increased caries risk.2,15

Dental hygienists can adjust the dental operatory to address the needs of patients with CREST. Consider keeping the surrounding environment in the dental operatory warm for patients who have vasospasms in order to avoid a vascular crisis.2,15 Providing blankets or gloves will aid in temperature control. A humidifier in the operatory might be helpful as the hydration may ease skin tension.15 Patients should be scheduled in the morning for brief appointments.2,15,17 Nitrous oxide can be used to treat patient anxiety, and oxygen should be available for those with restrictive lung diseases.2

Preventing periodontitis is critical for patients with CREST. Biofilm management techniques for self-care must consider limitations caused by the syndrome, and self-care instructions need to be adapted as conditions progress. Mental health status is also a factor when educating patients in oral hygiene techniques, as depression is common in these patients and can affect self-care motivation. When patients exhibit signs of depression, referrals should be made to mental health professionals for further evaluation and treatment.21

Frequent toothbrushing is key for maximum biofilm management.21 Chlorhexidine is also helpful in overall bacterial reduction, treatment of gingival inflammation, and prevention of root caries and candida.15 Power toothbrushes with child-size brush heads and handled interdental aides promote better biofilm control in patients with limited dexterity.14,15,19,21 In fact, a multifaceted oral health intervention, including the use of a power toothbrush and adapted flosser, and orofacial exercise, has been shown to be superior to standard self-care devices in improving gingival health.19 Flossing or interdental cleaning in the evening has been shown to decrease gingival inflammation in affected patients.14,21 A small, child-size toothbrush head is recommended due to limited mouth opening, and end-tuft toothbrushes can be utilized in cases of severe microstomia.14,15

Specific treatments are contraindicated when performing dental prophylaxis on patients with CREST. Air polishers and ultrasonic scalers should not be used due to the risk of aspiration when fibrosis of the soft palate and dysphagia are present. High-volume suction is mandatory because of aspiration risks.15 Additionally, four-handed dentistry is recommended for ease of treatment. A dental assistant can aid the dental hygienist in the retraction of oral tissues in areas of increased fibrosis. Epinephrine is contraindicated due to limited vascularization; therefore, a 3% local anesthetic solution is recommended.16 Surgical procedures should be avoided when possible due to reduced healing capacity and risk of post-operative complications.17

The most important consideration is to understand patients’ limitations and to help them adapt. Dental hygienists play an important role in assisting patients to maintain oral hygiene, identifying oral manifestations, providing self-care education, as well as modifying treatment to ensure safe, compassionate, and effective care.15 As the disease progresses, dental hygienists may need to initiate routine oral care plans with a caregiver by providing instructions for daily biofilm management and a self-exercise program that enables preventive care to be delivered. Dental hygienists can serve as consultants to caregivers, adapting oral health aides/devices as needed.

CONCLUSION

As the oral cavity is often an indicator of systemic health, dental hygienists are in a unique position to note the first signs of CREST syndrome.23 A persistent complaint of GERD, xerostomia, and limited mouth opening might alert practitioners to the possible presence of CREST. Effective oral hygiene instruction, along with frequent assessment and periodontal management are essential measures to preserve the oral health of those with CREST syndrome.

References

- Chaffee NR. CREST syndrome: clinical manifestations and dental management. J Prosthodont. 1998;7:155–160.

- Albilia JB, Lam DK, Blanas N, Clokie CM, Sándor GK. Small mouths…big problems? A review of scleroderma and its oral health implications. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:831–838.

- Lauritano D, Bussolati A, Baldoni M, Leonida A. Scleroderma and CREST syndrome: a case report in dentistry. Minerva Stomatol. 2011;60:443–465.

- Yoon JC. CREST syndrome. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1064663-overview. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- Hunzelmann N, Genth E, Krieg T, et al. The registry of the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma: frequency of disease subsets and patterns of organ involvement. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1185–1192.

- Mayes M, Lacey JV Jr, Beebe-Dimmer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246–2255.

- Jimenez SA, Derk CT. Following the molecular pathways toward an understanding of the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:37–50.

- Ganda K. Dentist’s Guide to Medical Conditions and Complications. 2nd ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2013:589–623.

- Ito M, Kojima T, Miyata M, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)-CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly and telangiectasia) overlap syndrome complicated by Sjögren’s syndrome and arthritis. Intern Med. 1995;34:451–454.

- McNair S, Hategan A, Bourgeois JA, Losier B. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in scleroderma. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:382–386.

- Chifflot H, Fautrel B, Sordet C, Chatelus E, Sibilia J. Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum.2008;37:223–235.

- Alpert MA, Pressly TA, Mukerji V, et al. Acute and long-term effects of nifedipine on pulmonary and systemic hemodynamics in patients with pulmonary/ hypertension associated with diffuse systemic sclerosis, the CREST syndrome and mixed connective tissue disease. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:1687–1691.

- Pope J, Fenlon D, Thompson A, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000956.

- Yuen HK, Weng Y, Reed SG, Summerlin LM, Silver RM. Factors associated with gingival inflammation among adults with systemic sclerosis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2014;12:55–61.

- Tolle SL. Scleroderma: considerations for dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:77–83.

- Alantar A, Cabane J, Hachulla E, et al. Recommendations for the care of oral involvement in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1126–1133.

- Fischer DJ, Patton LL. Scleroderma: oral manifestations and treatment challenges. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20:240–244.

- Pizzo G, Scardina GA, Messina P. Effects of a nonsurgical exercise program on the decreased mouth opening in patients with systemic scleroderma. Clin Oral Investig. 2003;7:175–178.

- Yuen HK, Weng Y, Bandyopadhyay D, Reed SG, Leite RS, Silver RM. Effect of a multi-faceted intervention on gingival health among adults with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(2 Suppl 65):S26.

- Fardal O, Lygre H. Management of periodontal disease in patients using calcium channel blockers: Gingival overgrowth, prescribed medications, treatment responses and added treatment costs. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:640–646.

- Yuen HK, Hant FN, Hatfield C, Summerlin LM, Smith EA, Silver RM. Factors associated with oral hygiene practices among adults with systemic sclerosis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2014;12:180–186.

- Poulsen S. Fluoride-containing gels, mouth rinses, and varnishes: An update of evidence of efficacy. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:157–161.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/Report/ExecutiveSummary.htm. Accessed January 10, 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2016;14(02):49–52.