Keeping Current

This course was developed in part with an unrestricted educational grant from Colgate Oral Pharmaceuticals.

This course was published in the February 2010 issue and expires February 2013. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the need for staying current with evidence.

- Define evidence-based decision-making and identify the skills needed to implement it.

- Define clinical decision support (CDS) and its goals.

- Discuss the hierarchy and value of pre-appraised evidence.

- Identify CDS resources available for clinicians.

FROM THE GUEST EDITOR

I am honored to be serving as the guest editor for a six article series, sponsored by Colgate-Palmolive Co, that will appear in Dimensions of Dental Hygiene from February through July of this year. The series—Leveraging Scientific Evidence to Improve the Oral Health Practices of Patients—will assist dental hygienists in becoming more familiar with reviewing the literature and scientific evidence and determining their validity. The first article discusses the importance of instituting an evidence-based model of learning into practice. Both Dr. Forrest and Dr. Newman are key opinion leaders in this area and their insights will help you understand how to search for scientific evidence, make decisions for patients’ point of care options, and incorporate them into your daily work routine. —Christine A. Hovliaras, RDH, BS, MBA, CDE, Guest Editor

The desire to improve the oral health of patients must start with the clinician’s commitment to keep up-to-date with important and useful scientific knowledge. The challenge for dental hygienists is to integrate new knowledge appropriately into their daily practices in order to improve their patients’ health.

The number of published articles, new devices, products, and drugs has increased faster than most clinicians can learn on their own, and yet as professionals, dental hygienists have an ethical responsibility to provide the most appropriate care to their patients. Many studies have shown widespread discrepancies among practitioners and their ability to stay current and, in some cases, those variations are beyond the range of acceptability. For those who don’t have time to devote to this never-ending process, it’s hard to imagine telling a patient you’re too busy to give him or her the best evidence-based care.

Adverse Drug Events

One area where keeping current cuts across practice domains is information about new drugs and medications. Most adults (80%) use prescription medications, over-the-counter drugs, or dietary supplements, and nearly one-third of adults take five or more different medications.1

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the frequency of medical errors and injuries due to medication, known as adverse drug events (ADEs), has become more common and costly.2 For example, findings from studies reviewed estimate that 450,000 preventable ADEs occur in hospitals, 800,000 preventable ADEs occur each year in long-term care facilities, and more than 530,000 preventable medication errors occur yearly in the outpatient Medicare population. The IOM study committee concluded that more than 1.5 million preventable ADEs occur each year in the United States, and this is likely a conservative estimate. These errors cost billions of dollars, not including lost earnings or compensation for pain and suffering.2

Management of patients with complex medical conditions is becoming more difficult in dentistry. With the increasing prevalence of chronic illnesses and the high use of prescription and over-thecounter medications by dental patients, keeping current with the evidence about the use of drugs is extremely important but also challenging. Being familiar with medications and drug interactions, the aging process, and physiologic changes that affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs makes it easier to avoid ADEs and improve oral health outcomes.

When clinicians are not aware of critical patient-specific information and/or base patient treatment on the use of old information, old technology, or unsubstantiated techniques, the chance that patients will receive substandard care increases. Thus, failure to bridge the gap between important clinical research evidence and what is performed in practice has the potential to jeopardize patient safety and decrease the quality of care they should receive.

EBDM and Clinical Decision Support Systems

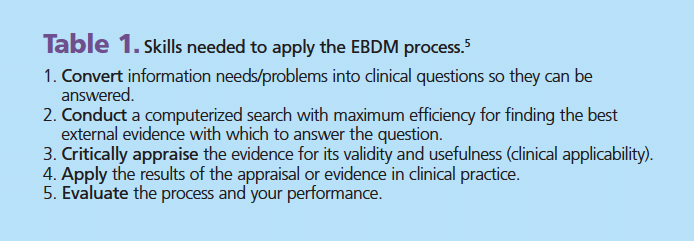

One approach to help clinicians bridge the gap between current research evidence and practice protocols is through self-directed evidence- based decision making (EBDM).3 EBDM is defined as “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.”4 As a result, practitioners need more efficient and effective online searching skills to find relevant evidence, and critical appraisal skills to rapidly evaluate the evidence for its validity and applicability. Table 1 outlines the skills related to the EBDM process.5

Learning these skills can be difficult for practitioners without formal searching and evidence-based training. Traditionally, the first step in the EBDM process requires writing a PICO question where the specific problem (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), and outcome (O) are identified. This is necessary in order to narrow the focus and establish key terms for conducting an effective search. Learning how to write a PICO question is important for those conducting research or a systematic review, especially when preappraised evidence is not available. More information on EBDM concepts, formulating PICO questions, conducting a PubMed search, appraising, and applying the evidence can be found in several articles and online courses.6-9

With the advancement of computerized searching tool algorithms, more efficient ways are now available for finding evidence. For example, PubMed (http://pubmed.gov) now has the Clinical Queries feature ( www .ncbi .nlm .nih.gov/ sites/ pubmed utils/ clinical), which uses evidence-based filters to streamline the process to quickly find relevant articles. By typing in a topic (eg, “lasers and periodontal therapy”) under the category “Find Systematic Reviews,” nine high-quality citations were found vs 428 citations of varying quality found through a traditional PubMed Search. Using Clinical Queries simplifies the first two steps in the EBDM process since the “Find Systematic Reviews” feature conducts a search for only your highest levels of evidence, ie, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and guidelines. However, depending on the type of citation returned, it still may require critical appraisal of the evidence in order to get to the bottom line—the clinical application.

What is CDS?

Clinical decision support (CDS) provides clinicians, staff, patients, and others with knowledge and person-specific information—intelligently filtered or presented at appropriate times—to enhance health and health care.10 According to A Roadmap for National Action on Clinical Decision Support, “The goal of CDS is to provide the right information, to the right person, in the right format, through the right channel, at the right point in workflow to improve health and health care decisions and outcomes.”11 For example, CDS can provide support throughout the care process ranging from preventive care through diagnosis and treatment planning to monitoring and follow-up. Interventions can range from detecting potential medical errors to ensuring that the best clinical knowledge and recommendations are used to improve health management decisions.11,12 The use of CDS is one of the best ways for clinicians to get evidence-based research into practice.

CDS includes a variety of printed and electronic tools that make knowledge readily available to help clinicians make more informed and individualized health care decisions. Some of these tools include computerized alerts and reminders, drug-dosing calculators, antibiotic management, clinical guidelines, order sets, patient data reports, and diagnostic support.

Four key features associated with a decision support system’s ability to improve clinical practice are:

- Decision support is provided automatically as part of clinician workflow,

- Decision support is delivered at the time and location of decision making,

- Actionable recommendations are provided, and

- CDS is computer based.

All four features make it easier for clinicians to use a CDS system, suggesting that an effective system must minimize the effort required by clinicians to receive and act on system recommendations.

Clinical Decision Support at the Point of Care

13 of pre-appraised evidence (Figure 1). When integrated with an electronic health record, the individual patient’s characteristics are automatically linked to the current best evidence that matches his or her specific circumstances. This can greatly assist the clinician by providing suggestions for appropriate care, warning of possible ADEs, and applying new information through the analysis of patient-specific clinical variables.

13 of pre-appraised evidence (Figure 1). When integrated with an electronic health record, the individual patient’s characteristics are automatically linked to the current best evidence that matches his or her specific circumstances. This can greatly assist the clinician by providing suggestions for appropriate care, warning of possible ADEs, and applying new information through the analysis of patient-specific clinical variables.

CDSS may differ in their focus. Some may be used to enhance diagnostic efforts, whereas other systems provide support in antibiotic management and drug-dosing calculations. However, in each of these cases, CDSS require input of patient-specific clinical variables in order to provide patient-specific recommendations. This requirement distinguishes them from clinical practice guidelines, which are broader in scope and provide more general care and treatment suggestions.14

One of the most common support systems is drug-dosing calculators that calculate appropriate doses of medication after entering key data such as patient weight, indication for drug, and serum creatinine.14 This level of support can reduce errors and result in improved patient safety and quality of care. Therefore, having a computerized CDSS that is integrated with the patient record can enhance the use of the most relevant clinical evidence.

Making greater use of information technologies and having all prescribers and pharmacies use electronic prescriptions (e-prescriptions) is one of the IOM’s important goals for 2010.15 By writing prescriptions electronically, providers can avoid common mistakes that accompany handwritten prescriptions, since the software ensures that all the necessary information is filled out and is legible. Furthermore, the integration of e-prescriptions with the patient’s medical history makes it possible to check automatically for drug allergies, interactions, and other potential problems.15 Once in the system, e-prescriptions also can promote continuity of care and communication among those involved with the patient’s care.

In addition to the CDSS that integrates the patient record, pointof- care drug reference information can be accessed over the Internet by personal digital assistants (PDAs). By linking to one of several drug database websites directly or through application programs, providers can obtain detailed information about the particular drug they want to prescribe, drug interactions, and get help in deciding if it is an appropriate drug to prescribe.

CDSS Tools and Evidence-Based Resources

The infrastructure to support the application of evidence at the point of care is evolving. However until patient records are integrated with a CDSS, evidence resources can be accessed via the Internet and all but the lowest level provides access to pre-appraised summaries.

Pre-appraised means that the research evidence has undergone a filtering process to include only those studies that are of higher quality, and they are regularly updated so that the evidence accessed through these resources is current.13 To facilitate use of the many pre-appraised resources, the 6S hierarchy of pre-appraised evidence can be used as a guide (Figure 1).

Ideally, an electronic medical record incorporates a CDSS that links the patient’s characteristics with current best evidence. If so, searching for evidence need not go further down the model. If a CDSS does not exist, the next best step is to look for Summaries. These include clinical pathways that integrate evidence-based information about specific clinical problems and provide regular updating. In dentistry and dental hygiene, these are more likely to be found as clinical practice guidelines that are based on a full range of evidence from the lower levels (individual studies —> synopses of systematic reviews). If no evidence is available at the Summaries level, the next step would be to look for Synopses of Systematic Reviews, which can be found in such journals as the Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice and Evidence- Based Dentistry. Table 2 presents examples of resources that support CDS.16

Ideally, an electronic medical record incorporates a CDSS that links the patient’s characteristics with current best evidence. If so, searching for evidence need not go further down the model. If a CDSS does not exist, the next best step is to look for Summaries. These include clinical pathways that integrate evidence-based information about specific clinical problems and provide regular updating. In dentistry and dental hygiene, these are more likely to be found as clinical practice guidelines that are based on a full range of evidence from the lower levels (individual studies —> synopses of systematic reviews). If no evidence is available at the Summaries level, the next step would be to look for Synopses of Systematic Reviews, which can be found in such journals as the Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice and Evidence- Based Dentistry. Table 2 presents examples of resources that support CDS.16

Becoming proficient in electronic information management can increase confidence in the quality of dental practice, and in the future, this daily activity may be sufficient for earning continuing education credit. This makes a lot of sense, because every time clinicians go online to access information, they will learn something. If this activity is repeated many times a day, it can add up to a considerable investment of effort.

Clearly clinicians need to stay current with clinical research evidence that can help to improve oral health outcomes. The development of skills using information systems is necessary to enhance the movement of research information to the point of care (chairside) in order to ensure that better treatment decisions are made. One of the first tasks is to verify that the knowledge base is valid, reliable, and useful.

Many resources are available that analyze the quality of research. The hierarchy of evidence- based resources provides an excellent guide for clinical decision support. In many cases, the pre-appraised summaries of evidence from the original published article are graded and the bottom-line clinical application is provided to make efforts more efficient.

A great variety of patient safety issues can be beneficially affected by CDS systems, preventing adverse drug reactions and inappropriate drug dosing as well as promoting appropriate use of effective prophylactic measures and helping to ensure a minimum standard for quality of care. The ability to access CDSS at the point of care allows the clinician to make the most appropriate clinical decision for his/her patient and decrease potential medical and medication errors.

Good CDS should assist rather than detract from normal daily activities. How to fit CDS into a busy practice is a challenge. Making scientific evidence and clinical best practices information more accessible makes the information more useful. If the information is more useful it will be more readily integrated into practice.

REFERENCES

- Aspden P, Wolcott JA, Palugod RL, Bastien T. Report Brief, July 2006. Institutes of Medicine. Available at: www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report Files/2006/Preventing-Medication-Errors-Quality-Chasm-Series/medicationerrorsnew.ashx. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- Aspden P, Wolcott JA, Bootman L, Cronenwett L. Preventing Medication Errors. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, IOM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2000.

- Sackett D, Straus S, Richardson W. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice & Teach EBM. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- Rosenberg W, Donald A. Evidence based medicine: an approach to clinical problem-solving. BMJ. 1995;310:1122-1126.

- Miller SA, Forrest JL. Translating evidence based decision making into practice: appraising and applying the evidence. J Evid Based Dent Prac. 2009;9:164-182.

- Forrest JL. Introduction to the basics of evidence-based dentistry: concepts and skills. J Evid Based Dent Prac. 2009;9:108-112.

- Forrest JL, Miller SA. Strategies for Searching the Literature Using PubMed. Available at: www.dentalcare.com/en-US/login.do?next Url=/en-US/ceEnter.do?id=340. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- Forrest JL. Evidence-based decision making: introduction and formulating good clinical questions. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;1:42-52.

- Osheroff JA, Pifer EA, Teich JM, Sittig DF, Jenders RA. Improving Outcomes with Clinical Decision Support: An Implementer’s Guide. Chicago: Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society Press; 2005.

- Oshreroff JA, Teich JM, Middleton BF, Steen EB, Wright A, Detmer DE. A Roadmap for National Action on Clinical Decision Support, June 13, 2006. Available at: www.amia.org/files/cdsroadmap.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- Berner ES. Clinical decision support systems: state of the art. Available at: http://healthit.ahrq.gov/images/jun09 cds review/ 09_ 0069_ef.html. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- DiCenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB. Accessing preappraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. ACP Journal Club. 2009;151:JC3-2-JC3-3.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- Aspden P, Wolcott JA, Palugod RL, Bastien T. Report Brief, July 2006. IOM, Available at: www.iom .edu/ ~/media/ Files/Report%20Files/ 2006/Preventing-Medication-Errors-Quality-Chasm-Series/ medicationerrorsnew.ashx. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- Newman MG. Clinical decision support complements evidence-based decision making in dental practice. J Evid Base Dent Pract. 2007;7:1-5.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2010; 8(2) Insert.