Treating the Transgender Patient

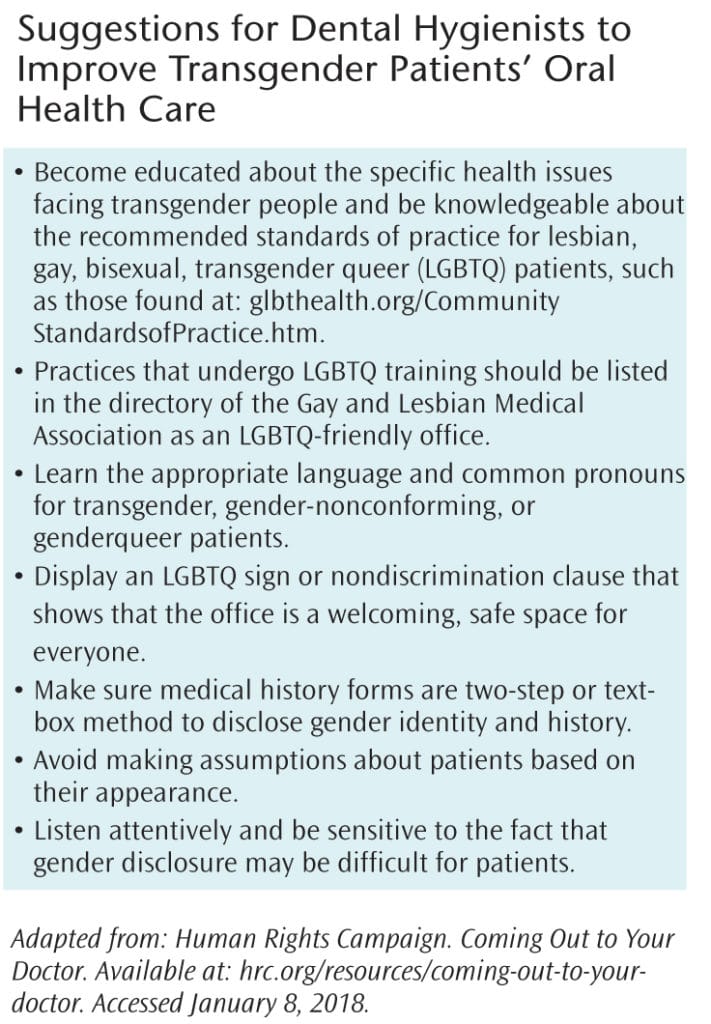

Following are strategies to support oral health professionals in their efforts to meet the needs of this patient population and to identify barriers to care.

This course was published in the January 2018 issue and expires January 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the demographics of the transgender population.

- Explain the barriers to health care faced by transgender patients.

- List the goals and systemic indications of hormone therapies.

- Discuss the role of the dental hygienist when treating the transgender patient.

Approximately 4.1% of the United States population identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender.1 Research suggests that there are at least 1.4 million transgender people in the US, about 0.6% of the population.2 This estimate is likely conservative, as it is difficult to measure the entire population.2 Despite the increased visibility of transgender celebrities like Caitlyn Jenner, many people may not personally know anyone who is transgender.

This article explores ways oral health professionals can be better prepared to meet the needs of transgender and gender-nonconforming patients, identifies barriers to care for this population, and highlights the oral-care implications of gender-affirming therapies, such as hormone therapies. Ultimately, we aim to better prepare oral health professionals to meet the needs of this population.

DEMOGRAPHICS

There is limited information available about oral health care within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) population, especially the transgender population.3 In fact, many health care history forms contain no check box for this population. Oral health care is a determinant of overall health, yet access to it remains a challenge for millions of Americans.4 With the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles—an academic think tank that conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender-identity law and public policy—estimating that more than 1 million transgender people live in the US, practices with more than 200 patients should expect to treat at least one transgender patient.2

Little research has been conducted on the oral implications of transitioning, social implications, and barriers to care. Much information about the transgender community must be gathered from the limited research on the larger LGBTQ community.3

BARRIERS TO CARE

Social stigma against transgender people is significant and widespread,5,6 and has been shown to be a negative determinant of health.5 The negative psychological response to stigma is termed “minority stress,” which is when minority groups face chronic levels of increased stress.7 Transgender individuals are at increased risk of anxiety and depression due to this stress.6 Minority stress is socially induced and not inherent to identifying as transgender or gender nonconforming.8

A recent national survey of transgender people found that 40% of transgender individuals have attempted suicide, roughly nine times the rate of attempted suicide among the US population overall. The survey estimates that between 45% and 74% of transgender individuals smoke, and their alcohol consumption is also high. Approximately 30% of transgender individuals report using illegal drugs or misusing prescription medication within the past month, a rate that is three times the national average. The prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection in this population is significantly higher than the average, 1.4% vs 0.3%.9

Transgender people also report high levels of discrimination from health care providers. For instance, 23% note that they did not seek needed health care in the previous year because they feared mistreatment.9 Similarly, 33% reported they did not seek health care within the past year when it was needed because they could not afford it.9 In fact, the unemployment rate of transgender people was found to be three times higher than the unemployment rate in the US at the time the survey was taken.9 Of those with insurance, 25% experienced problems with denied coverage related to their care.9

Multiple studies have shown that transgender people face barriers to health care caused by lack of adequate insurance coverage, bias from health care providers, and providers’ inexperience at treating transgender patients.8,10

MEETING PATIENTS WHERE THEY ARE

MEETING PATIENTS WHERE THEY ARE

Promoting a welcoming environment not only encourages transgender patients to seek care, but may also increase their post-treatment compliance and the likelihood that they’ll return for follow-up appointments.11 Many transgender patients are prescribed hormones to align their bodies with their gender identity, and many undergo surgery, but hormones and surgery are not part of every transgender person’s experience. A transgender identity is not necessarily dependent on physical appearance or medical procedures.

Efforts should be made to meet patients “where they are” without judgment or preconceptions. Oral health professionals should take care not to editorialize a patient’s gender identity, including making remarks about the person’s appearance. This effort will enhance the patient-provider relationship and avoid the perception of stigmas.11

VOCABULARY

Vocabulary is important when communicating about transgender issues and identities. Gender is a set of social, psychological, and emotional traits, often influenced by societal expectations that classify an individual as feminine, masculine, androgynous, or other, whereas sex refers to birth genitalia and/or biological characteristics.12 The word transgender, sometimes written as just trans or trans* with an asterisk, is commonly used as an umbrella term to refer to an individual whose sense of gender does not correspond with the person’s birth sex. Some prefer a different vocabulary, choosing to identify as genderqueer, gender fluid, gender variant, bigender, pangender, etc.13

The term cisgender is used to describe individuals whose sex and gender align. Some people also identify as gender nonconforming or nonbinary; their behavior or appearance does not conform to the cultural and social expectations for their gender. A gender-nonconforming individual may present with aspects of both stereotypical gender identities, such as a beard and high heels, or may choose to present more androgynously.13

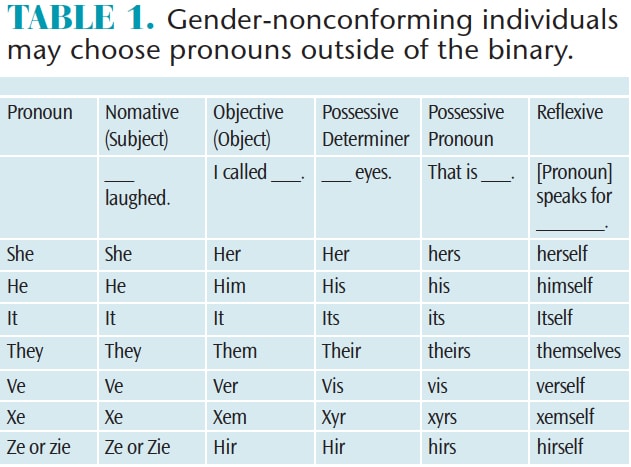

Gender-nonconforming individuals may choose pronouns outside of the binary of “he” and “she.” Thus, they may choose pronouns such as ve, xe, or ze and the respective conjugations. Other gender-nonconforming people switch between gendered pronouns, using both she and he. A large portion of gender-nonconforming people ask to be referred to as they, choosing the plural pronoun and sidestepping the gendered use of she or he (Table 1).13

It is important to use the word transgender as an adjective. A person is not “a transgender,” but rather a “transgender person.” Avoid the extraneous “-ed,” as an individual is not “transgendered,” but, again, a “transgender person.” The term transsexual, though preferred by some, is often seen as outdated and may be considered inflammatory. Defamatory language includes terms like tranny and she-male.13

Many people, including health care providers, are fearful of using incorrect or disrespectful language when addressing or referring to transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Transgender and gender-nonconforming people, as well as support networks, report that respectful mistakes are readily corrected with goodwill.14 All attempts should be made to respect and use a person’s chosen gender pronouns. Using someone’s unchosen name or gender pronouns may be considered disrespectful and can act as a barrier to care.15 It is important to note that one’s gender identity and sexual orientation are disparate. Someone can change from female to male (or vice versa) and be attracted to men, women, both, or not interested in sexual relationships at all.16

GENDER-AFFIRMING INTERVENTIONS AND SYSTEMIC INDICATIONS

Previous terminology, such as sex change and gender reassignment, has been declinicalized. Currently, the term gender-affirmation interventions or gender-affirmation surgery is used to describe the various ways individuals choose to align their bodies with their gender identity. These may include chest binding, genital tucking or packing, hair removal, hormone therapies, and surgery. The primary medical therapy is gender-affirming hormone treatments. Hormone therapy allows individuals to present secondary sex characteristics in line with their gender identity.17

The goal of feminizing hormone therapy is the development of female secondary sex characteristics and suppression of male secondary sex characteristics. Feminizing hormone therapies combine estrogen with an androgen blocker. These therapies are not without risk, as there are many serious and at times life-threatening side effects, such as pulmonary embolism and stroke.18

In fact, transgender women may not report chest pain or trouble breathing because they fear their providers may halt hormone treatments. Another risk is the use of nonmedical-grade pharmaceuticals by women who don’t have access to supportive health care. These interventions include hormones and silicone fillers that may be sold and injected by nonmedical personnel, increasing health risks such as use of shared needles.18

Side effects of feminizing estrogen therapies may include migraines, mood swings, hot flashes, and weight gain. Venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, and stroke are also associated with this therapy, exacerbated by tobacco use. Estrogen therapy alone is correlated with cardiovascular events in patients older than 50 with underlying risk factors.18 Compounding risk factors include obesity and smoking, and risk is also affected by hormone dose and the delivery system.18

Side effects of feminizing estrogen therapies may include migraines, mood swings, hot flashes, and weight gain. Venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, and stroke are also associated with this therapy, exacerbated by tobacco use. Estrogen therapy alone is correlated with cardiovascular events in patients older than 50 with underlying risk factors.18 Compounding risk factors include obesity and smoking, and risk is also affected by hormone dose and the delivery system.18

In fact, oral estrogen therapies have been correlated with an increase in triglycerides, which raises the risk of pancreatitis and cardiovascular events. Estrogen therapy also increases the potential for gallstones (cholelithiasis) and gallbladder surgeries. To a lesser extent, estrogen therapy is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, particularly among patients with a family history or risk factors for the disease. Estrogen therapy has also been associated with changes in blood pressure.18

The goal of masculinizing hormone therapy is the development of male secondary sex characteristics while suppressing secondary female sex characteristics. Masculinizing hormone therapies use bioidentical parenteral testosterone, chemically equivalent to testosterone secreted by the testicle. This therapy may be altered by age 50, around the time when many women undergo menopause.18

Masculinizing hormone therapy may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with underlying risks factors. Transgender males may face an increase in metabolic disorders, a rise in their body mass index, and an increase in polycystic ovarian syndrome.18,19 Also, testosterone levels in transgender men are hard to maintain at target levels, which may lead to hormone fluctuations that exacerbate side effects.19 Even though the risk for these diseases is likely increased in transgender persons taking these hormones, few long-term studies have been conducted.

ORAL IMPLICATIONS

ORAL IMPLICATIONS

Health care providers need to know the oral implications of gender-affirmation therapies so they can posit follow-up medical history questions adequately. As the oral mucosa, gingiva, and salivary glands contain estrogen receptors, variations in hormone levels directly affect the oral cavity. An overly severe inflammatory reaction, such as that often seen during puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, should be expected in patients undergoing hormone therapies.20

Fluctuating sex hormones such as estrogen and progestin are associated with an exaggerated inflammatory reaction, hormone-influenced gingivitis, and increased instances of pyogenic granulomas.20 Gingivitis is more severe in times of changes or imbalances in estrogen and progestin levels.21Hormonal variations may even influence changes in the periodontium.21

Sex hormones affect microcirculation producing swelling, adherence of granulocytes and platelets to blood vessel walls, increase vessel permeability, and disrupt the function of mast cells.21 Estrogen deficiency has been associated with the increased activity of immune cells and osteoclasts which may increase cytokine production, a protein associated with periodontal disease and bone resorption.21

In addition to a greater incidence of gingivitis and periodontitis, there may also be an increase in xerostomia, lichen planus, pemphigoid, Sjögren’s syndrome, and burning mouth syndrome, as observed during menopause.21

ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

A comprehensive evaluation of the oral mucosal membranes, periodontal and dental conditions, and salivary flow, along with a detailed clinical history, is imperative for patients, especially those using hormone replacement therapy. To maintain oral hygiene, brushing, interdental care, mouthrinsing, and fluoride use are critical to improve overall periodontal health and prevent caries.22

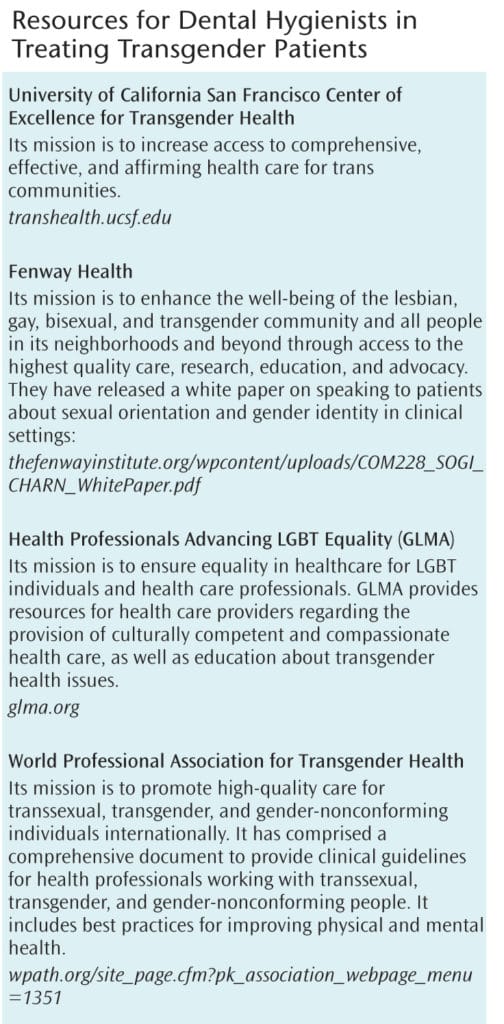

In addition to assessing dental health needs, dental hygienists should consider the mental, emotional, physical, and social aspects of health.22 Patients’ socioeconomic status and their ability to access health care are also important considerations. Oral health professionals should have the language and knowledge to support patients as they navigate the health care system. An interprofessional collaborative approach may be required to provide holistic care for this patient population.

OFFICE TRAINING AND SETTING

The entire office staff should be provided training about transgender and gender-nonconforming language. LGBTQ or transgender-themed pamphlets and magazines could be included in the materials placed in waiting rooms to indicate acceptance of this population. All bathrooms should be gender-neutral or indicate that patients may choose rooms based on their gender identity. If bathrooms are labeled, at least one gender-neutral bathroom should be available to provide a space for gender-nonconforming people, as well as for those in transition and who may feel uncomfortable in any gendered space.11

The transgender population should also be accurately and respectfully reflected on forms. On intake forms, transgender and gender-nonconforming patients should be able to identify themselves. Some practices have added a “transgender” check box, in addition to “male” and “female” ones. However, the most supportive method is to have a text box for patients to write in their self-identified gender.23 Inclusive forms may also ask patients their preferred pronouns.

Updates should offer patients the option to change their preferred name and gender identity. Insurance forms may reflect the outdated names and gender identities of patients. Thus, intake forms should state both birth name and birth sex, as well as gender identity and preferred names. Forms other than intake forms should represent only the patient’s preferred gender identity and preferred name, and strides should be taken to use the patient’s preferred name and preferred pronouns.11

SUMMARY

Transgender patients have unique but diverse health needs that are best addressed by holistic and interprofessional approaches. Dental hygienists should be aware of the barriers to care unique to transgender patients and gain insight into the skills necessary to communicate with and provide patient care. As health care professionals, dental hygienists should continue to learn about transgender persons to address their evolving needs.

REFERENCES

- Gallup. In US, More Adults Identifying as LGBT. Available at: gallup.com/poll/201731/lgbt-identification-rises.aspx. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TNT. How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? Available at: williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/How-Many-Adults-Identify-as-Transgender-in-the-United-States.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Russell S, More F. Addressing health disparities via coordination of care and interprofessional education: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health and oral health care. Den Clin N Am. 2016;60:891–906.

- National Governors Association. The role of dental hygienists in providing access to oral health care. Available at: nga.org/cms/home/nga-center-for-best-practices/center-publications/page-health-publications/col2-content/main-content-list/the-role-of-dental-hygienists-in.html. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Bellatorre A, Lee Y, Finch B, Muennig P, Fiscella K. Structural Stigma and All-Cause Mortality in Sexual Minority Populations. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:33–41.

- Rood BA, Reisner SL, Surace FI, Puckett JA, Maroney MR, Pantalone DW. Expecting Rejection: Understanding the Minority Stress Experiences of Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1:151–164.

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697.

- Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2012;13(4:165–232.

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 US Transgender Survey. Available at: transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF. Accessed December 17, 2017.

- Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:713–719.

- Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People: Creating a safe and welcoming clinic environment. Available at: transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=guidelines-clinic-environment. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- New York University. LGBTQ Terminology. NYU Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Student Center. Available at: nyu.edu/students/communities-and-groups/student-diversity/lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender-and-queer-student-center/glossary-of-important-lgbt-terms.html. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- GLAAD. Media Reference Guide—Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual Glossary of Terms. Available at: glaad.org/reference/lgbtq. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- West Virginia University. Proper Pronoun Usage. TItle IX and Office of Equity Assurance at WVU Available at: titleix.wvu.edu/information-for/transgender/proper-pronoun-usage. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Stotzer R, Silverschanz P, Wilson A. Gender identity and social services: barriers to care. Journal of Social Service Research. 2013;39(1):63–77.

- GLAAD. Transgender FAQ. Available at: glaad.org/transgender/transfaq. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Deutsch M. Overview of gender affirming treatments and procedures. Available at: transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=guidelines-overview. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Hickey M, Elliott J, Davison SL. Hormone replacement therapy. BMJ. 2012;344:763.

- Deutsch MB, Bhakri V, Kubicek K. Effects of cross-sex hormone treatment on transgender women and men. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:605–610.

- Mariotti A. Dental plaque-induced gingival diseases. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:7–19.

- Grover CM, More VP, Singh N, Grover S. Crosstalk between hormones and oral health in the mid-life of women: A comprehensive review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2014 ;4(Suppl 1):S5–S10.

- Wilkins EM, Wyche CJ, Boyd LD, eds. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Human Rights Campaign. Collecting Transgender-Inclusive Gender Data in Workplace. Available at: hrc.org/resources/collecting-transgender-inclusive-gender-data-in-workplace-and-other-surveys. Accessed December 27, 2017.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2018;16(01):48-51.