Brush Up on the Basics of PPE

The appropriate use of personal protective equipment is integral to the safe provision of oral health care services.

Infection control is critical in the provision of oral health care to protect both patients and clinicians. Oral health professionals and patients rely on experts at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to provide evidence-based rules, recommendations, and guidelines related to workplace safety and the delivery of safe patient care. This article focuses on the safety aspects of personal protective equipment (PPE) set forth by OSHA.

REGULATORY AGENCIES AND ADVISORY BODIES

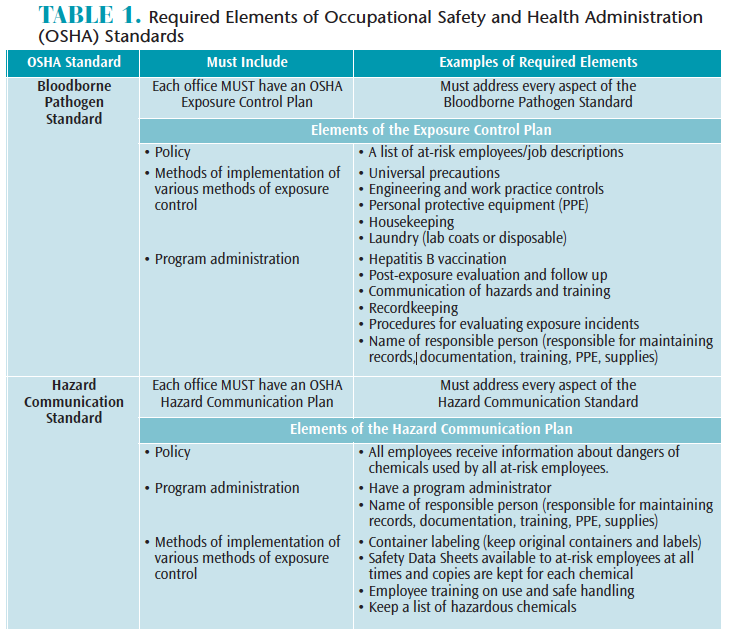

OSHA was founded in 1971 to protect workers in response to high numbers of workplace injuries and death.1 In 1970, nearly 14,000 workers were killed on the job.1 By 2010, this number fell dramatically to approximately 4,300.1 OSHA is a regulatory agency that ensures workplace safety with enforcement capability, allowing its representatives to investigate and impose fines. Two OSHA standards that dental offices must comply with are: the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030)2 and the Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200).3 The required elements of each standard are described in Table 1.

OSHA mandates protection from bloodborne pathogens in the workplace, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV), for all oral health professionals with exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials (OPIM).2 One element of OSHA’s bloodborne pathogens standard requires employers to provide protection from bloodborne pathogens through the use of PPE, such as gloves; masks; protective eyewear; protective garments (eg, lab coats and their laundering); HBV vaccination; safe work practices, including safety devices (eg, sharps containers, needle recapping devices); and annual training.2

OSHA also mandates protection from chemical hazards in the workplace. Employers must provide training and PPE foremployees handling chemicals.3 Many types of chemicals are used in the dental office including liquids, such as surface disinfectants, cleaning and housekeeping agents, and dental materials. All chemicals on the market must contain a Safety Data Sheet (SDS) providing workers with information on safe handling, including methods for storage, disposal, and first aid instructions in the event of accidental exposure. Current SDS information must be kept for every chemical used in the office and must be made accessible for at-risk employees at all times.3

The CDC is an advisory body that publishes evidence-based infection control recommendations that help clinicians understand and comply with the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. The CDC’s Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003 contains guidance for the use of PPE to prevent splash and spatter to the skin and mucous membranes (eyes, nose, and mouth).4 Splash, spatter, and aerosols that are potentially infectious from blood, saliva, and microorganisms are generated by handpieces, powered instrumentation, and rinsing. PPE includes gloves, surgical face masks, protective eyewear, and protective clothing such as lab coats.4 The CDC published companion documents in 2016 outlining its recommendations and basic expectations for safe care.5 The CDC guidelines, along with OSHA standards, help oral health professionals make sense of the expectations for safe care and increase compliance.

GLOVES

Practicing effective hand hygiene and using gloves are the best prevention strategies in disease transmission. Handwashing or the use of an alcohol-based hand gel before and after gloving is important to avoid wicking. Wicking is a process of drawing in or absorbing moisture or microorganisms through the glove, which could contaminate the hands.5–7 Microorganisms thrive in the warm and moist environment of gloves. Although adequate, gloves do not provide a 100% barrier due to permeability of the glove material. Several factors can affect permeability, such as glove thickness, temperature, humidity, and skin pH. The longer a glove is worn, the more permeable (and less effective) it will become,8,9 so changing gloves frequently helps to eliminate the issue of permeability. Therefore, it is vital to wash or sanitize hands before and after gloving.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates and considers gloves as medical devices. They must meet certain performance standards for leaks (permeability) and tear-resistant capabilities.8,9 It is important to use the appropriate type of glove for the intended task. Puncture-resistant heavy duty utility gloves must be used when there is a risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens or chemicals. Utility gloves must be used when handling contaminated instruments during instrument reprocessing, as well as when handling chemicals such as disinfectants (wipes and sprays) during operatory clean up. Utility gloves can be steam autoclaved.2,3 Medical grade examination gloves are used for patient-care procedures and can be either sterile or nonsterile. Sterile gloves are used during surgical procedures, while nonsterile gloves are used for routine patient-care procedures. Several types of examination gloves, made from various chemicals, are available and include latex, vinyl, neoprene, and nitrile. Choosing the appropriate glove for the task helps reduce the potential for disease transmission to patients and promotes safety.10

MASKS

Splash and spatter of potentially infectious aerosols and chemicals to mucous membranes or “portals of entry” are a concern for oral health professionals. Wearing the appropriate mask and eyewear can aid in preventing this problem. The CDC’s Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003 recommends that masks should be changed between patients, when they become wet from breath or splash, during handling of chemicals, and during patient care with highly aerosolized procedures (every 20 minutes).4 Wet masks can lead to wicking, rendering the mask ineffective.4 A seal should be created covering the nose and mouth,2,4 and be comfortable without any gaps, which might allow microorganisms to penetrate. It is best to avoid touching masks with hands or gloves.11–13 After just 40 minutes of high-speed handpiece use, high counts of microorganisms have been found on masks of oral health professionals.14 Masks must be worn under face shields to reduce inhalation of microbial-laden aerosols.4Reusing masks or putting them in pockets has the potential to spread microorganisms and contaminate hands and clothing.

Face masks are considered single-use disposable medical devices by the FDA15 and are used for a variety of tasks in dentistry. The type of mask chosen depends on the task at hand. Some of these tasks range from brief examinations to procedures involving splash, spatter, and aerosols.16,17 Procedures involving the potential for splash and aerosols require a higher level of filtration. Masks with limited or no filtration are best suited as a physical barrier in situations where splash or aerosols are not generated, such as conducting brief oral examinations, developing radiographs, or handling chemicals.16,17

Maximum filtration masks such as N95 respirators, approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, provide protection from small virus particles and are used for treating patients in isolation settings with severe respiratory airborne diseases and are not used for routine dental procedures.

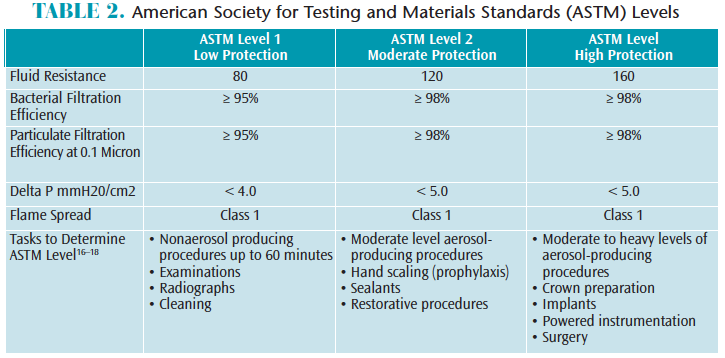

The American Society for Testing and Materials Standards (ASTM) F2100-11 rates surgical face masks for bacterial filtration efficiency (BFE), submicron particulate filtration efficiency (PFE), delta P differential pressure, fluid resistance, and flammability.18Most dental aerosols are 5.0 microns or less in diameter, so masks with at least 95% BFE and PFE are recommended for dental procedures involving aerosol generation, such as ultrasonic scaling and high-speed handpiece use.16,17 ASTM filtration levels are classified as low, moderate, or high to help clinicians decide which mask is appropriate for the task at hand (Table 2).

There are many factors to consider when choosing the appropriate mask, such as comfort, temperature, and breathability.16,17 Delta P differential penetration represents the air flow measured in mmH20/cm2; therefore, masks with a higher delta P differential provide better filtration but less breathability.17,18 Masks are a required part of routine safe patient care. The selection and level of compliance depend on several factors, including ASTM level for type of procedure being performed, comfort, and cost.

PROTECTIVE EYEWEAR

Protective eyewear with solid side shields or the use of a face shield with a mask are required to protect eyes from splash, spatter, and aerosols.4 High-speed projectiles of dental materials, aerosols, splash from chemicals, and spatter of blood or OPIM can cause serious injuries to the eyes, so it is imperative that both patients and oral health professionals wear eye protection that is approved by the American National Standards Institute. The use of soap and water to clean eyewear between patients is recommended, unless visibly soiled, then a disinfection step should be included.4

PROTECTIVE CLOTHING

Protective clothing, such as lab coats or disposable gowns, prevents contamination of skin and street clothes. It is important to cover street clothing and skin (especially the forearms) that might be exposed to blood or OPIM during dental procedures.4 Protective clothing and laundering must be provided by the employer, according the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard.2 Employers may choose on-site laundering or laundering through a service vendor that specializes in handling contaminated items.2 Protective clothing should be changed when visibly soiled and should not be worn outside of the treatment area.4

DONNING AND REMOVAL OF PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT

Donning (placement) and doffing (removal) of PPE should be conducted in a logical and systematic order:

- Protective clothing (lab coat) should be placed first over scrubs or street clothes.

- Next place a mask over the nose and mouth, molding to fit the nasal bridge and checking for a seal.

- Don protective eyewear with side shields

- Don examination gloves by holding at the cuff and maneuvering the hand and fingers inside to achieve the correct fit.10

Removal of PPE should follow in the reverse order by taking off gloves first, utilizing the opposite hand to remove one glove, then the second glove is removed with the pinky finger hooked into the cuff area (to avoid contaminating bare skin) pulling downward turning the glove inside out. Next, remove the mask using bare hands handling only the elastic strings.16 Eyewear is then removed. The last step is removal of the lab coat, followed by handwashing or hand sanitizing.10

CONCLUSION

Employers and staff are responsible for protecting themselves from bloodborne pathogens and chemical hazards in the workplace. Choosing the right PPE for the task at hand and knowing how to properly use it ensures safety in the workplace.

REFERENCES

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Timeline of OSHA’s 40 Year History. Available at: osha.gov/osha40/timeline.html. Accessed September 27, 2017.

- OSHA. Bloodborne Pathogens Standard 29 CFR. 1910.1030. Available at: osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=standards&p_id=10051. Accessed September 27, 2017.

- OSHA. Hazard Communication Standard 29 CFR 1910.1200. Available at: osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=standards&p_id=10099. Accessed September 27, 2017.

- Kohn WG, Harte JA, Malvitz DM, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–66.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/guidelines/index.htm. Accessed September 27, 2017.

- Miller CH, Palenik CJ. Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, Elsevier; 2010.

- Harte JA, Molinari JA. Instruments cassettes for office safety and infection control. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2007;28:596–600.

- American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). Annual Book of ASTM Standards. Philadelphia: ASTM; 2012.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Premarket Notification [510(K)] Submissions for Testing for Skin Sensitization to Chemicals in Natural Rubber Products. Available at: fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm073793.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2017.

- Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures (OSAP). From Policies to Practice: Osap’s Guide the Guidelines: Workbook. Annapolis, Maryland: OSAP; 2004.

- Wilson JA, Loveday HP, Hoffman PN, Pratt RJ. Uniform: an evidence review of the microbiological significance of uniforms and uniform policy in the prevention and control of health-care associated infections. Report to the department of health (England). J Hosp Infect. 2007;66:301–307.

- Davies-Cole J, Lyss S, Blair J. Norovirus outbreak in an elementary school—District of Columbia, February 2007. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;56:1340–1343.

- Li RW, Leung KWC, Sun FCS, Samaranayake LP. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and the GDP. Part III: implications for GDP’s. Br Dent J. 2004;197:130–134.

- Rautema R, Nordberg A, Wuolijoki-Saaristo K, Meurman JH. Bacterial aerosols in dental practice—a potential hospital infection problem? J Hosp Infect. 2006;64:76–81.

- FDA. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Surgical Masks. Accessed at: fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm072549.htm. Accessed September 26, 2017.

- Molinari J, Nelson P. Face masks what to wear and when. The Dental Advisor. Available at: dentaladvisor.com/pdf-download/?pdf_url=wp-content/uploads/2015/02/face-masks-what-to-wear-and-when.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2017.

- Molinari J, Nelson P. Face mask performance: Are you protected? Available at:medicom.com/uploads/files/Medicom%20Face%20Mask%20Performance%20Article_v3(1).pdf. Accessed September 26, 2017.

- ASTM. Standard Specification for Performance of Materials Used in Medical Face Masks. Available at: astm.org/Standards/F2100.htm. Accessed September 26, 2017.

Featured image by WAVEBREAKMEDIA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2017;15(10):23-26.