wildpixel / iStock / Getty Images Plus

wildpixel / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Periodontal Treatments Defined

While the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology published an improved classification of periodontal diseases in 2018, the clinical application of the new classification as a guide to the delivery of care for patients in need of periodontal treatment is often unclear.

The grade of a case is extremely important in determining the long-term prognosis of a patient but it requires more than a single evaluation of the patient. Once the speed of disease progression has been determined and a grade assigned, treatments can be recommended.1

Definition of Treatments

Self-Care Instruction. The need for meticulous self-care can’t be overemphasized. Not only does quality self-care help preserve oral health, it also facilitates ongoing diagnoses and disease management. Absent quality self-care, it’s difficult to determine if a site that shows persistent signs of inflammation (eg, bleeding on probing) is experiencing gingival or periodontal inflammation. This distinction can be important because gingivitis is easily addressed, whereas persistent periodontitis calls for additional scaling and root planing (SRP) and frequently advanced periodontal therapy.

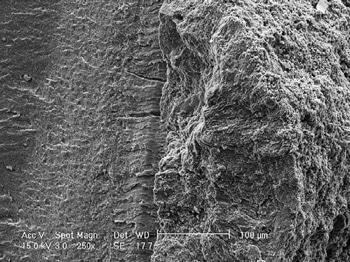

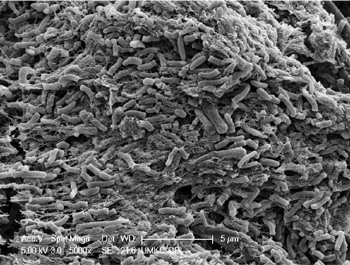

SRP. This periodontal therapy removes calculus and roughness from the root surfaces of diseased (periodontally involved) teeth. Unfortunately, the removal of all calculus from the root surface can be very difficult if the teeth have more than a few millimeters of periodontal pocketing. While bacterial plaque is the proximate cause of periodontal degeneration, once subgingival calculus has formed, it must be completely removed from the root for SRP to be a successful treatment for periodontal diseases. So-called “disinfection of the root surface” (removal of subgingival surface plaque but not subgingival calculus) is inadequate when subgingival calculus is present. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show that bacteria are harbored in residual calculus.

Studies show that even sterile calculus is cytotoxic, meaning it kills periodontal cells.3 There are many clinical observations that residual calculus is present at sites that do not respond adequately to periodontal treatment. Also, multiple studies have shown that skilled operators with unlimited operating time frequently leave a large percentage of undisturbed and fractured calculus on root surfaces following routine closed (blind) SRP.4 Additional studies have shown that “microislands” of calculus remain after SRP even with direct (open) visualization of the root surfaces. Thus, residual and fractured subgingival calculus remaining after SRP is undoubtedly a major cause of inadequate treatment of periodontitis.5

Advanced Therapy. Advanced periodontal therapy goes beyond traditional closed SRP. Advanced therapy may involve advanced visualization techniques, such as the use of a videoscope or periodontal endoscope, surgical access for (open) debridement of the periodontal lesion, and/or soft or hard tissue regenerative procedures. The type of advanced therapy used should be an informed, educated, and justifiable decision made by the therapist. Repeated unsuccessful closed SRP does not represent advanced therapy. If closed SRP does not resolve signs of periodontal inflammation, the patient should be informed of the need for and availability of advanced therapy.

Laser-based periodontal therapy is sometimes promoted as a stand-alone substitute for closed SRP or as an adjunct to traditional SRP. However, assessment of nearly 30 years of comparative studies suggest no additive benefit to lasers.6 Advanced therapy may be performed by anyone who is adequately trained to legally perform such therapy. Nevertheless, no matter who performs it, advanced therapy necessitates a level of care equivalent to that expected of a fully trained periodontist.2

Reevaluation of Therapy. Reevaluation of the patient following all levels of periodontal therapy is mandatory in order to evaluate if the therapy has restored periodontal health. Depending on the treatment performed, patient reevaluation should occur at 6 weeks to 3 months post-therapy. If the patient returns to periodontal health after treatment, active therapy can be considered completed and the patient can be put on a maintenance schedule. If on reevaluation the patient continues to have inflammation, bleeding on probing, or deep pockets, the patient must be informed of the need for and availability of advanced care. Performing any level of periodontal therapy and not reevaluating the results and informing the patient of the availability of any necessary additional treatment or maintenance care, when appropriate, constitutes inadequate care.

Periodontal Maintenance. Periodontal disease is never completely cured but it can be controlled. Patients who have been diagnosed with periodontal disease (Stage I through Stage IV) and adequately treated should always be placed on a schedule aimed at maintaining periodontal health. Seminal to proper maintenance care are routine reevaluations to determine if active periodontitis has returned. Patients who continue to show signs of active periodontitis (Stage I through Stage IV) should not be placed in periodontal maintenance but should be provided advanced periodontal therapy.

References

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S1–S8.

- Harrel SK, Cobb CM, Sottosanti JS, Sheldon LN, Rethman MP. Clinical decisions based on the 2018 classification of periodontal diseases. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2020;43:52–56.

- Ziauddin SM, Alam MI, Mae M, et al. Cytotoxic effects of dental calculus particles and freeze-dried Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitansand Fusobacterium nucleatum on HSC-2 oral epithelial cells and THP-1 macrophages. J Periodontol. September 5, 2021. Online ahead of print.

- Caffesse RG, Sweeney PL, Smith BA. Scaling and root planing with and without periodontal flap surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:105–210.

- Harrel SK, Wilson TG Jr., Tunnell JC, Stenberg WV. Laser identification of residual microislands of calculus and their removal with chelation. J Periodontol.20;91:1562–1568.

- Cobb CM. Lasers and the treatment of periodontitis: the essence and the noise. Periodontol 2000. 2017;75:205–295.

This information originally appeared in Harrel SK, Rethman MP, Cobb CM, Sheldon LN, Sottosanti JS. Clinical decision points as guidelines for periodontal therapy. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2022;20(6)28–33.