Lyme Disease and Oral Health

Lyme disease—which is spread via tick bite—is the most common vector-borne disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States.

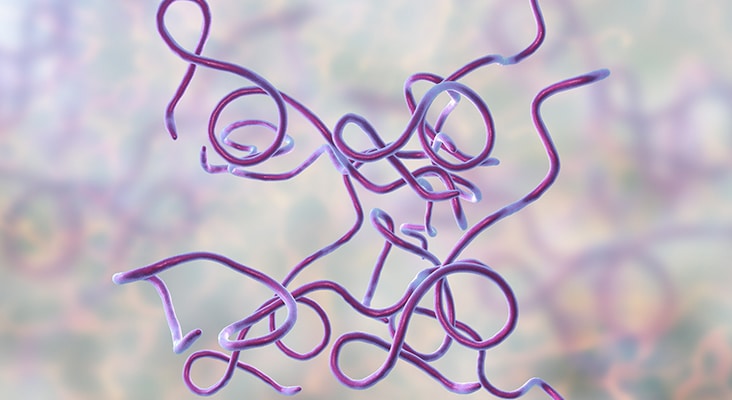

Lyme disease—which is spread via tick bite—is the most common vector-borne disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States. In 2017, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 42,743 confirmed cases of Lyme disease—an increase of 17% from 2016. While tick-borne infections are most common in the summer, due to increasingly warmer temperatures, ticks may still be active in the fall. The total number of Lyme disease cases is unknown because of the high prevalence of misdiagnoses. Lyme disease was first discovered in Lyme, Connecticut, in the mid-1970s when a large number of children presented with symptoms of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Upon further examination, the arthritic symptoms were also accompanied by cardiac and neurologic findings, as well as the clinical presence of an expanding rash, erythema migrans. In the early 1980s, Wilhelm Burgdorfer, PhD, and colleagues isolated an unspecified bacterium from deer ticks. Their analysis revealed that the unspecified coiled spirochete was the etiological host of Lyme disease. Named after the founder, the spirochete is now known as Borrelia burgdorferi.

Photo Credit: IgorChus / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Transmission of Lyme Disease

B. burgdorferi is spread through infected deer ticks and black-legged ticks. Ticks, which transfer the bacteria to humans via saliva through their bite, can transmit infection throughout their lives. Individuals living in suburban and rural areas are at highest risk of exposure. Ticks typically live in densely wooded areas, thick shrubs, high hedges, and small trees. They are unable to fly or jump, and often hold onto the tips of grass and shrubs with their lower legs, which is called “questing.” While ticks are questing, they climb onto a passing host and find an acceptable place to attach. Ticks require an area on the host that is well supplied with blood to feed, so they are usually found around the backs of the knees, armpits, groin, navel, and hair line. The infected tick needs to be attached to the host for approximately 24 hours to 48 hours to transfer the bacteria. Therefore, removing the tick at its earliest occurrence can reduce the risk of infection.

Photo Credit: royaltystockphoto / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Early Localized Stage

The early localized stage—which typically presents with the most common clinical manifestation of a “bull’s-eye” rash, or erythema migrans—occurs in approximately 80% of patients. Symptoms of erythema migrans usually appear at the site of a tick bite around 3 days to 30 days after exposure. The rash appears as a red macule or papule, erythematous, circular, and may have raised and warm borders. It can also appear as a target lesion and present with a vesicular and necrotic center. If untreated, erythema migrans increases in size by as much as 30 cm or more in diameter for days to weeks. Joint pain, fatigue, swollen glands, elevated temperature, stiff neck, conjunctivitis, difficulty concentrating, and sensitivity to light are common symptoms in the early localized stage. Oral symptoms may include transient periods of pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) or masticatory muscle, as well as limitations in opening the mouth. Patients experiencing facial pain due to Lyme disease are frequently wrongly diagnosed with temporomandibular disorders (TMDs). Most patients with early Lyme disease recover when treated with appropriate therapy.

Photo Credit: anakopa / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Early Disseminated Stage

The onset of the early disseminated stage appears from weeks to a few months after infection and transpires once B. burgdorferi invade the bloodstream and settle in remote areas within the body. The most common manifestation in this stage is multiple sites of erythema migrans. These alternative skin lesions consist of an arrangement of ring-shaped erythematous lesions similar to but generally smaller than the initial lesion seen in the early localized stage. Other manifestations include facial nerve palsy, acute lymphocytic meningitis, and neck stiffness. Additional symptoms such as feeling light-headed, palpitations, labored breathing, chest pain, and fainting may be related to Lyme carditis (when B. burgdorferi enter the tissues of the heart). Myalgia, fatigue, burning and shooting pain that radiates on the skin, and migratory musculoskeletal pain in joints and bone are also symptoms of this stage. Although rare, inflammation of the iris and optic nerve damage has also been reported.

Photo Credit: Himagine / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Late Persistent Stage

Disease progression in the late persistent stage occurs months to years after initial infection. The most common indicator is arthritis usually affecting large joints, specifically the knee. Although arthritis involvement can be migratory, typically five or fewer joints are affected. Other signs of Lyme arthritis may include inflammation of the tendons and TMJ pain. When the disease is untreated, damage to the nervous system occurs, causing Lyme neuroborreliosis, or a neurological manifestation of Lyme disease. The symptoms include inflammation of the brain, possible brain damage, and damage to the peripheral nerves. These signs often mimic other neurological diseases, which can lead to misdiagnosis. Studies show that exposure to the bacteria at any stage of Lyme disease can spread to the nervous system, joints, and other skin sites. However, the frequency of dissemination and the ability for the bacteria to persist varies, and early diagnosis is key to preventing further progression of disease.

Photo Credit: Anut21ng / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Treatment

Oral health professionals should be familiar with Lyme disease treatments. In 2010, the Infectious Diseases Society of America published updated treatment recommendations for Lyme disease, which include antibiotics for all stages. However, the duration and route of treatment regimens differ, depending on the stage of disease. Different measures of prophylactic therapy are used depending on the stage of disease, and the complexity of treatment can vary depending on the involvement of the systems. While doxycycline is the first method of treatment, it is not the drug of choice for all patients, including pregnant women and children younger than 8 due to the risk of tooth discoloration; amoxicillin should be used instead. Recognizing and treating Lyme disease during pregnancy is crucial, as research indicates an association between untreated disease and pregnancy problems, including premature birth, stillbirth, and spontaneous abortion.

Photo Credit: Professor25 / iStock / Getty Images Plus

In the Dental Chair

Oral health professionals can recognize the signs and symptoms of Lyme disease and make referrals to primary care physicians. They are particularly well suited for this because the Lyme disease symptoms of head and neck pain may motivate patients to seek dental treatment. A precise and comprehensive history of present illness, past medical history, and current social history must be acquired. The most common nondental orofacial pain condition associated with Lyme disease is a temporomandibular disorder (TMD), which may present as limitations in opening of the mouth, headache, facial pain, and joint clicking or popping. Patients presenting with symptoms manifesting as Lyme neuroborreliosis may have facial pain due to nerve involvement, whereas patients with symptoms of Lyme arthritis experience pain in the joints. Burning mouth syndrome is sometimes present in patients with Lyme disease. Ruling out other underlying diseases when treating patients with TMD symptoms is key to detecting Lyme disease. Investigating unclear, nonspecific TMDs, headaches, and facial pain is critical to preventing misdiagnosis.