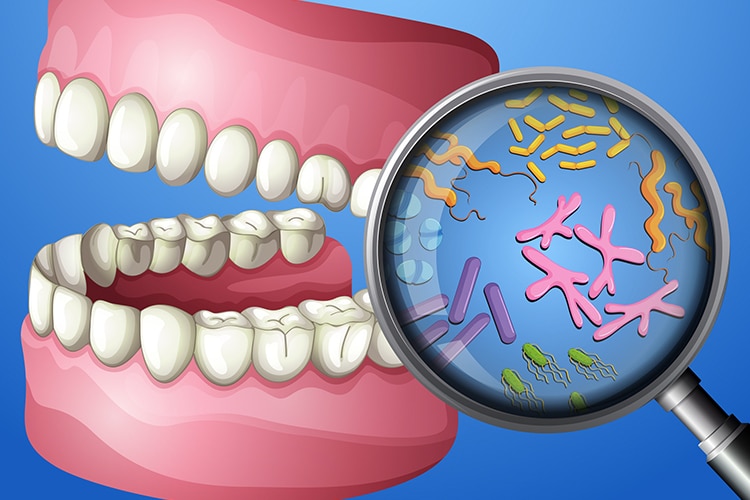

A Closer Look at the Oral Microbiome

The intimate relationship between the microbiome and the host is dynamic and influenced by many environmental factors such as diet, tobacco usage, and stress.

The intimate relationship between the microbiome and the host is dynamic and influenced by many environmental factors such as diet, tobacco usage, and stress. These—along with many other aspects of modern lifestyle—influence and alter our microbiome and its respective properties that cause a shift within the body’s ecosystem from a balance of health to disease, and vice versa. The oral cavity is one of the most heavily colonized parts of the human body and, therefore, susceptible to this shift equally if not more so than other areas of the body. To counteract this shift for disease prevention, clinicians must focus on the host and its microbiome residents as one, rather than separate entities.

Photo Credit: royaltystockphoto / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Database of Microorganisms

The oral cavity is inhabited by a vast and diverse mixture of microorganisms, including viruses, protozoa, fungi, archaea, and bacteria. To curate and record this information, the Forsyth Institute developed the Human Oral Microbiome Database in 2007. This online expanded database of human-associated microbiomes provides the scientific community with tools and information to help understand the role of microbiomes in health and disease. Currently, 770 microbial species have been enumerated, of which 57% are officially named, 13% unnamed but cultivated, and 30% are known as uncultivated phylotypes. The samples collected that make up this database are derived from a mixture of healthy subjects and subjects with more than a dozen disease states ranging from caries, periodontal diseases, endodontic infections, and cancer.

Photo Credit: colematt / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Development of the Microbiome

The mouth hosts a variety of bacteria due to the distinct habitats such as the tongue, attached gingiva, gingival sulcus, teeth, cheeks, lips, and hard and soft palates, which allow for microbial colonization. Therefore, the oral cavity represents a heterogenous ecological system that supports different microbiome communities. The moist areas of the mouth offer nutrients, such as salivary proteins, gingival crevicular fluid, and glycoproteins, that support the growth of many microorganisms. As teeth erupt, microbial colonization occurs almost instantly on new surfaces, which starts a major ecological event in the mouth of a child. This occurs again as primary teeth are replaced with their respective succedaneous teeth, which significantly alters the oral microbiome. The occlusal surface of teeth provide a shelter for microorganisms to persist in an extensive biofilm formation. Fixed dental prostheses can also influence the formation of a biofilm as well as affect the composition of the microbiome.

Photo Credit: Seregraff / iStock / Getty Images Plus

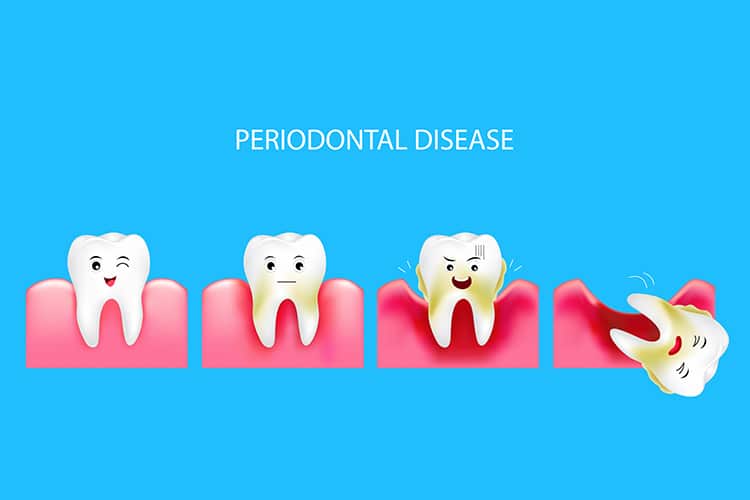

Microbial Imbalance

The host-immune response to pathogenic bacterial species has long been understood to result in periodontal diseases. The dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, of pathogenic bacteria results in oral microbiota that cause a negative and destructive relationship in the oral cavity. Many studies have successfully identified individual and specific oral microbiota that differ between health and disease. However, it has also been established that after periodontal treatment, the pathogenic species associated with periodontal disease tend to decrease. Additionally, there is a general trend for health-associated species to increase after periodontal treatment. Recent studies show that the shift of health-compatible to disease-associated microbiome is due to the relative proportional increase in pathogenic bacteria, and not due to the transmission of new bacteria from person-to-person.

Photo Credit: wowwa / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Maintaining Oral Microbiome Health

With the establishment of the oral microbiome, a process of maintaining homeostasis is regulated by resident bacteria through anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory responses to its environment, relative to the location within the oral cavity. Fortunately, in addition to the action of bacteria, the oral cavity contains saliva and gingival crevicular fluid to provide nutrients for the growth of microbes and aid in antimicrobial activities. One study identified 108 different microorganisms per milliliter of saliva, especially in areas such as the tongue. Saliva helps to promote oral health by facilitating in swallowing, mastication, and aiding digestion using specialized proteins and enzymes to help maintain a healthy oral microbiome. Enzymes act on the tooth surface acquired pellicle to trigger and mediate bacterial adherence. In addition to this, saliva helps modulate layers of plaque, which controls biofilm development and activity. Plaque biofilm can be removed naturally via the muscles of the tongue and cheeks during mastication and speech, as well as debridement with a toothbrush or a scaler.