IRA_EVVA / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

IRA_EVVA / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

What You Need to Know About Cannabis Use

The use of both medical and recreational cannabis is growing, putting the onus on dental hygienists to understand how to provide safe and effective care.

This course was published in the January 2023 issue and expires January 2026. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 010

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify United States Food and Drug Administration-approved cannabinoid drugs and recreationally used cannabis products.

- Discuss the therapeutic and adverse effects of these products.

- Note their possible effects on oral health and dental treatment.

The legislative status of medical and recreational cannabis use has undergone steady change over the past few years and a growing number of Americans favor its legalization. Oral health professionals are likely to encounter patients using various cannabis products and should be aware of current developments concerning their use, particularly the exponential growth of the recreational market.

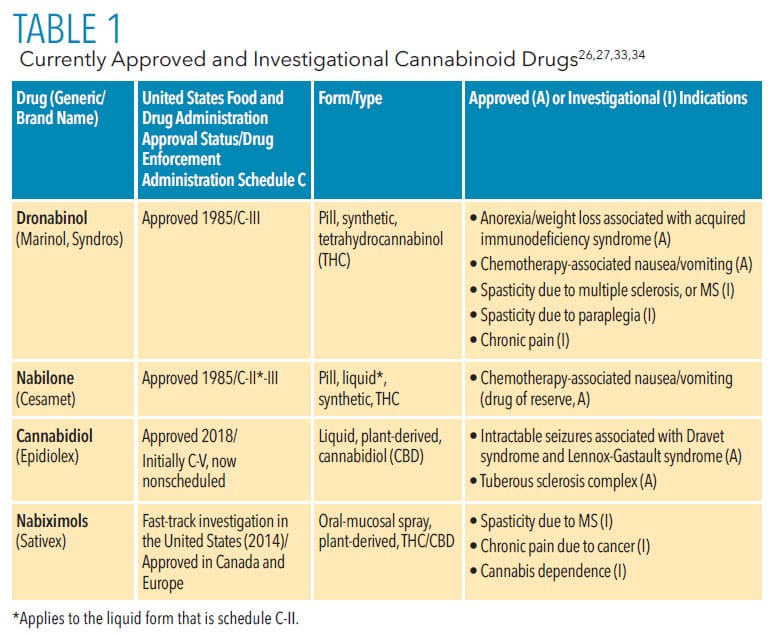

The evidence of effectiveness of cannabinoid drugs (Table 1)1–4 continues to grow. However, a plethora of cannabis formulations other than approved or investigational drugs are available legally, or are obtained outside of state-approved dispensaries. These products are not reviewed and approved for any medical indications by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5

There is also a growing number of over-the-counter products, including oral care products, that contain cannabidiol (CBD); some claim beneficial or even therapeutic effects, despite a lack of evaluation by the FDA for safety and effectiveness.5

Alarmingly, a synthetic isomer of delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) called delta-8 THC may be present in some widely available hemp-derived products that are escaping FDA oversight and regulation. This is due to misinterpretation of the US Farm Act of 2018.6–8 Delta-8 THC binds to the same cannabinoid receptors and is about 75% as potent as delta-9 THC. Products containing delta-8 THC may cause adverse effects and often include adulterants such as heavy metals and pesticides; bacterial contamination has also been reported.7,9 The US Cannabis Council (USCC)—a group supporting safe, regulated cannabis use—is calling on federal and state authorities to prevent the use of unregulated, untested cannabis products.9

Legislative Status and Cannabis Use

Currently, 38 states, the District of Columbia and several US territories have medical marijuana programs, and 19 of these have legalized adult recreational use to some degree. Many remaining states recognize medical uses with restrictions on levels of THC, the most commonly used psychoactive compound of the cannabis plant. While still technically illegal on a federal level, 27 states and the District of Columbia have decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana.10

Cannabis use has risen dramatically across all age groups, and while highest among ages 18 to 25, older adults (65 and older) have surprisingly shown a more than two-fold increase over the past several years.11,12

The incidence of cannabis use disorder has increased in recent years. With widespread availability of recreational cannabis, possible adverse effects and long-term harms may not be seriously considered, and daily users have been shown to face the highest risks.11–13

Recreational Cannabis

Legalization of cannabis for recreational use has spurred a number of public health concerns.11 Research is just beginning to elucidate whether legalization will impact the health and development of adolescent users, rates of motor-vehicle accidents, prevalence of cannabis abuse and dependence, and accidental consumption by children.14–18

Unanticipated problems regarding cannabis use have also surfaced such as its effect on lung function, particularly when consumed via vaping.19 Extracts used for vaping contain substances particularly dangerous to the lungs, such as vitamin E acetate, triglycerides, and other lipids.12

A relationship between legalization of recreational cannabis and opioid mortality due to overdose has been explored. Some early studies investigating this association found a notable decrease in opioid mortality following cannabis legalization.22 However, more recent research 11,23,24 examining cannabis use, opioid use/misuse, and related mortality suggest a need for a more careful analysis of any such correlation. This evidence suggests that additional factors may have played a role, such as a reduction in opioid prescribing.11

A special consideration related to recreational cannabis use in many jurisdictions is its impact on the utilization of medical cannabis, which is more widely available but more arduous to obtain.25 Medical cannabis and cannabinoid-based drugs have been researched for decades, despite the difficulties posed by their status as illegal substances federally and their designation as Schedule I drugs by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).26 The availability of cannabis products for recreational use may negatively impact medical cannabis research and use, as consumers may choose to obtain legally available cannabis products without any medical advice or supervision. The potential for misuse, adverse effects, and ineffective management of their medical conditions as a result of self-medicating is concerning. The USCC cautions that the unregulated use of available cannabis products can hinder the progress toward a safe and regulated legal cannabis industry.9

Cannabidiol Products

The same change in federal law that resulted in the recent surge of products containing delta-8-THC cannabis-related isomer also opened the gates for the flood of CBD products available over the counter without FDA approval.23 Research is currently investigating the therapeutic potential of this nonpsychoactive component of cannabis. Potential therapeutic targets for CBD include psychoses, anxiety, insomnia, insulin regulation, chronic pain, and epileptic seizures (the only indication for which there is an FDA-approved drug, cannabidiol).28

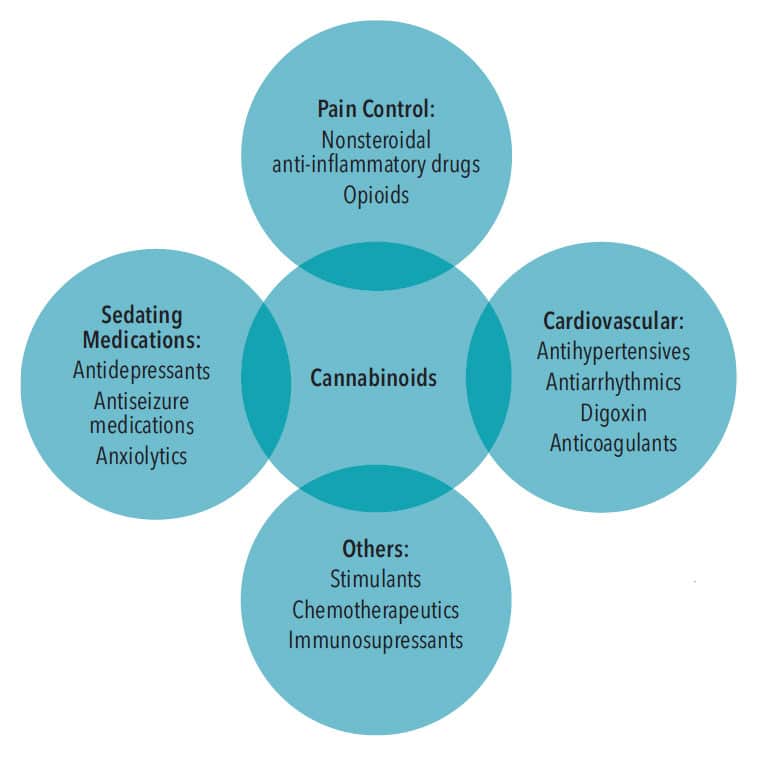

The public has unlimited access to thousands of CBD-containing products in stores and online. Meanwhile, the FDA is educating the public on potential harms of these unregulated substances, which include liver injury; male infertility; and drug interactions (Figure 1), particularly when combined with sedatives, such as alcohol, anxiolytics, and insomnia agents.29

The FDA is also proactively engaged in research by means of real-world data, which utilize electronic health records, insurance claims, and patient-generated information, as well as conventional evidence, which applies research analytics to the data generated.27

Cannabis use is particularly concerning in specific patient populations such as pregnant and breastfeeding women, children and adolescents, and older adults.12,15,18 Approximately16% of pregnant women use cannabis, most reportedly to alleviate nausea, improve appetite, decrease pain, and stabilize mood.12

Cannabinoids are small, lipophilic molecules that easily cross the placental barrier and prenatal exposure can affect fetal development, resulting in decreased fetal growth and adverse neonatal outcomes as well as long-term physical and medical consequences.12 Cannabinoids are also excreted in breast milk, and the effects of early exposure by breastfeeding needs more study; however, breastfeeding mothers are advised to avoid cannabis use.12

US adults ages 65 and older have increased their cannabis use by 250%

Cannabidiol is the only FDA-approved cannabinoid drug for children as young as 1 with rare seizure disorders. It has undergone extensive review for safety and effectiveness prior to its approval, so its adverse effects are known and continue to be studied.1,12 However, pediatric use of cannabis is not limited to this approved medication as many state medical cannabis programs list numerous conditions qualifying for medical cannabis treatment for which the level of evidence is much lower.1,2 Additionally, the rate of accidental exposure to cannabis in preparations appealing to children has grown following legalization.11,18

Increased hospitalizations and fatal outcomes due to cardiac toxicity leading to cardiac arrest have been reported in infants and young children.11,30 Meanwhile, a longitudinal study of adolescent use demonstrated effects on brain development revealed by cortical thinning especially in the prefrontal cortex of the frontal lobe.15 The outcomes of these findings are yet to be corroborated by future neurobehavioral, psychological, and public health studies; however, there appears to be no increase in adolescent use following legalization so far.11,14

US adults ages 65 and older have increased their cannabis use by 250%, while those ages 50 to 64 have boosted their use by 60%.12 Comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, and medication use for management of chronic conditions are particularly concerning when cannabinoid drugs, or cannabis for medical or recreational use, are added. The risk for adverse reactions due to drug interactions can endanger these patients, so a careful health and medication use history, including questions about cannabis use, is essential to prevent negative health outcomes.12

Effects of Cannabinoids on Oral Health

The significant expression of cannabinoid receptors is found in many oral tissues including the tongue, salivary glands, oral mucosa, periodontal tissues, and even dental pulp; this has sparked the study of associated adverse oral effects as well as some therapeutic applications. Association of cannabis use with increased gustatory sensation with sweet foods is well documented, along with increased incidence of dental caries in chronic users.31 However, recent studies reveal stimulation of these receptors may be associated with the pathogenesis of more serious diseases such as mobile tongue squamous cell carcinoma and burning mouth syndrome.31,32

Diminished salivary secretion is the most commonly reported oral adverse effect of cannabis use and is attributed to anticholinergic action on salivary flow as well as possible inflammation of glandular tissues. It does not appear to be limited to smoked cannabis products.31,32 Other oral mucosal effects include increased occurrence of leukoedema, hyperkeratosis, nicotine stomatitis (independent of tobacco use), and higher incidence of oral candidiasis, the latter attributed to immune suppression and an affinity of Candida albicans for the hydrocarbons in cannabis smoke.32 Oropharyngeal cancers have been most strongly associated with smoked cannabis and are more likely with the concurrent and frequent use of alcohol.2

Several earlier reviews indicated increased incidence and severity of periodontal diseases among frequent cannabis users. More recent studies, however, have mixed results, likely attributable to confounding factors of oral hygiene, concurrent tobacco use, systemic disease, and varied amounts and routes of administration of cannabis products.2

Several earlier reviews indicated increased incidence and severity of periodontal diseases among frequent cannabis users. More recent studies, however, have mixed results, likely attributable to confounding factors of oral hygiene, concurrent tobacco use, systemic disease, and varied amounts and routes of administration of cannabis products.2

Implications for Dental Treatment

Dental treatment considerations begin with informed professionals obtaining a medical history inclusive of recreational/self-medicating substances as well as medically authorized and prescribed medication.32 Determining the safety of planned or emergent dental procedures may be complex, as adverse effects of cannabis consumption can vary among new vs chronic users, recreational vs medical use, time of administration, dosage, dose form, and current medical status.33 After documenting the level of exposure to cannabis as well as use patterns, clinicians should assess patients’ vitals and watch for signs of hypertension, bradycardia/tachycardia, arrhythmias, hyperactive airway, and orthostatic hypotension, all of which are associated with cannabis use, some up to 72 hours after consumption.33 This is especially concerning if administration of local anesthesia with vasoconstrictors is planned. Conscious sedation is contraindicated within the 72-hour time frame.30

Once safety has been established, screening and education regarding oral adverse effects of cannabis use, particularly if products are smoked/vaped, should be implemented. If a patient is using cannabis products for anxiety associated with dental treatment, legal informed consent should be obtained when a patient is not under the influence. More standardized guidelines for cannabis use specific to the dental setting are needed. Validated screening tools for suspected misuse or cannabis use disorder are readily available.30 A proactive office policy on cannabis use that is clearly communicated to staff and patients will prevent miscommunication and unnecessary rescheduling of patients.34

Conclusion

The growing popularity of cannabis-based products is accompanied by a corresponding increase in health and practice concerns. Oral health professionals are responsible for keeping abreast of emerging evidence and following recommendations as they are established to ensure the safe delivery of dental care.

References

- Jugl S, Okpeku A, Costales B, et al. A mapping literature review of medical cannabis clinical outcomes and quality of evidence in approved conditions in the USA from 2016 to 2019. Med Cannabis Cannabinoids. 2021;4:21–42.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Available at: nap.edu/catalog/⤑/the-health-effects-of-cannabis-and-cannabinoids-the-current-state. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Drug Comprised of an Active Ingredient Derived from Marijuana to Treat Rare, Severe Forms of Epilepsy. Available at: fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm611046.htm. Accessed November 10, 2022.

- Lintzeris N, BhardwaJ A, Mills L, et al. Nabiximols for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1242–1253.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD). Available at: fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd. Accessed November 10, 2023.

- Kruger JS, Kruger DJ. Delta-8-THC: Delta-9-THC’s nicer younger sibling? J Cannabis Res. 2022;4:4.

- Meehan-Atrash J, Rahman I. Novel Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol vaporizers contain unlabeled adulterants, unintended byproducts of chemical synthesis, and heavy metals. Chem Res Toxicol. 2022;35:73–76.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. 5 Things to Know about Delta-8 Tetrahydrocannabinol—Delta-8 THC. Available at: fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/䁳-things-know-about-delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol-delta-8-thc. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- United States Cannabis Council. Delta-8 THC Table of Contents. Available at: irp.cdn-website.com/윳d7ca/files/uploaded/USCC%20Delta-8%20Kit.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- National Conference of State Legislators. Cannabis Overview. Available at: ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/marijuana-overview.aspx. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- Leung J, Chiu V, Chan GCK, Stjepanović D, Hall WD. What have been the public health impacts of cannabis legalisation in the usa? a review of evidence on adverse and beneficial effects. Curr Addict Rep. 2019;6:418–428.

- Brown JD, Rivera KJR, Hernandez LYC, et al. Natural and synthetic cannabinoids: pharmacology, uses, adverse drug events, and drug interactions. J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;61:S37–S52.

- Sherman BJ, McRae‐Clark AL. Treatment of cannabis use disorder: current science and future outlook. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2016;36:511–535.

- Melchior M, Nakamura A, Bolze C, et al. Does liberalisation of cannabis policy influence levels of use in adolescents and young adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025880.

- Albaugh MD, Ottino-Gonzalez J, Sidwell A, et al. Association of cannabis use during adolescence with neurodevelopment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:1–11.

- Santaella-Tenorio J, Wheeler-Martin K, DiMaggio CJ, et al. Association of recreational cannabis laws in colorado and washington state with changes in traffic fatalities, 2005-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1061–1068.

- Leung J, Chiu CYV, Stjepanović D, Hall W. Has the legalisation of medical and recreational cannabis use in the USA affected the prevalence of cannabis use and cannabis use disorders? Curr Addict Rep. 2018;5:403–417.

- Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. Unintentional cannabis ingestion in children: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2017;190:142–152.

- Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Evans-Polce RJ, Veliz PT. Cannabis, vaping, and respiratory symptoms in a probability sample of US youth. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:149–152.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. Available at: cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. November 10, 2023.

- Gaiha SM, Lempert LK, Halpern-Felsher B. Underage youth and young adult e-cigarette use and access before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2027572-e2027572.

- Livingston MD, Barnett TE, Delcher C, Wagenaar AC. Recreational cannabis legalization and opioid-related deaths in Colorado, 2000–2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1827–1829.

- Gorfinkel LR, Stohl M, Greenstein E, Aharonovich E, Olfson M, Hasin D. Is cannabis being used as a substitute for non-medical opioids by adults with problem substance use in the United States? A within-person analysis. Addiction. 2021;116:1113–1121.

- Shover CL, Davis CS, Gordon SC, Humphreys K. Association between medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality has reversed over time. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116:12624–12626.

- Matthews A, Stramoski S. The therapeutic potential of medical marijuana. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2017;15(5):41–44.

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Scheduling. Available at: dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling. Accessed November 10, 2022.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Better Data for a Better Understanding of the Use and Safety Profile of Cannabidiol (CBD) Products. Available at: fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/better-data-better-understanding-use-and-safety-profile-cannabidiol-cbd-products. Accessed November 10, 2022.

- Peng J, Fan M, An C, Ni F, Huang W, Luo J. A narrative review of molecular mechanism and therapeutic effect of cannabidiol (CBD). Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2022 Apr;130:439–456.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. What You Need to Know (And What We’re Working to Find Out) About Products Containing Cannabis or Cannabis-derived Compounds, Including CBD. Available at: fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/what-you-need-know-and-what-were-working-find-out-about-products-containing-cannabis-or-cannabis. Accessed November 11, 2022.

- Nappe TM, Hoyte CO. Pediatric death due to myocarditis after exposure to cannabis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2017;1:166-170.

- Bellocchio L, Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM, et al. Cannabinoids drugs and oral health—from recreational side-effects to medicinal purposes: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8329.

- Keboa MT, Enriquez N, Martel M, Nicolau B, Macdonald ME. Oral health implications of cannabis smoking: a rapid evidence review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2020;86:1–10.

- Echeverria-Villalobos M, Todeschini AB, Stoicea N, Fiorda-Diaz J, Weaver T, Bergese SD. Perioperative care of cannabis users: a comprehensive review of pharmacological and anesthetic considerations. J Clin Anesth. 2019;57:41–49.

- Chafee BW. Cannabis use and oral health in a national cohort of adults. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2021;49:493–501.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2023; 21(1)28,34-37.