CHERRYBEANS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

CHERRYBEANS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Tips for Treating Patients With Sleep Apnea

Supporting patient compliance with treatment and addressing oral health implications are key to improving the health of patients with this common disorder.

This course was published in the December 2019 issue and expires December 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Recognize the three types of sleep apnea and which type is the most common.

- Discuss how sleep apnea is diagnosed and treated.

- Identify health risks associated with sleep apnea.

- Develop a plan to improve compliance with treatment and provide care for patients undergoing positive airway pressure treatment.

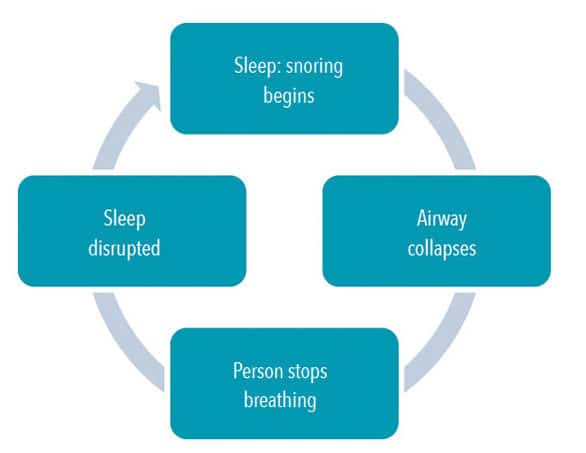

In the United States, sleep apnea affects approximately 5.9 million adults.1 The three types of sleep apnea are obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in which the airway is blocked, either partially or fully, usually when the tongue and/or soft palate collapses against the back of the throat during sleep; central sleep apnea in which the brain does not signal the muscles to breathe; and complex sleep apnea, a combination of the two conditions. OSA is the most common form.2 Positive airway pressure therapy is the standard of care for all three types.2

Dental hygienists are well-positioned to provide screening for all types of systemic health problems, including OSA. Several OSA screening protocols and questionnaires are available, including the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, STOP Questionnaire, STOP-Bang Questionnaire, and the Apnea Risk Evaluation System Questionnaire.3–6

DIAGNOSIS

The severity of OSA is typically measured using the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), which is determined through polysomnography in a sleep facility (Table 1).7 Polysomnography is the gold standard for OSA diagnosis, however, it can be costly, inconvenient, and time consuming.8 Home sleep apnea testing (HSAT) is an alternative for patients with risk factors for OSA such as obesity, age, snoring, gasping/witnessed apneas, and sleepiness.9,10 While patients may feel more comfortable completing a sleep test at home, there is concern about the accuracy of such tests. Because HSAT devices usually do not use electroencephalography (EEG), as polysomnography does, to score sleep-wake states, total recording time rather than total sleep time is scored. This potentially alters the value of the AHI, and, as a result, the severity of OSA may be underestimated.9

TREATING SLEEP APNEA

Treatment is based on the severity of OSA and patient compliance. Treatment modalities include positive airway pressure therapies, anterior mandibular positioners, and hypoglossal nerve stimulation surgeries.

CONTINUOUS POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices are the most commonly used in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe OSA.11 A CPAP machine consists of a hose with a mask that covers the nose, or in some cases the nose and mouth, attached to a machine that forces air through the nostrils into the airway, preventing airway collapse.11 CPAP greatly improves quality of life because patients experience more restful, restorative sleep with less fatigue and irritability and improved cognitive function.11

BILEVEL AIRWAY PRESSURE

Bilevel airway pressure (BiPAP) is another device with a similar mode of operation to CPAP and is often used when CPAP therapy is ineffective. The difference between CPAP and BiPAP is the former’s continuous pressure vs a two-pressure system. Bilevel airway pressure machines have a two-pressure system that can be set by the patient. The higher pressure setting is for inhalation, and the lower pressure setting is for exhalation. Some patients prefer this device to the CPAP, which provides higher, continuous pressure that can be difficult to exhale against. Additionally with the BiPAP, if the patient has a hypopnea episode, it switches to a second mode, or controlled ventilation. This creates a higher pressure that causes forced inhalation, allowing patients to breathe easier. For patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or other obstructive pulmonary disorders in which exhalation is difficult, BiPAP is recommended.12

VARIABLE POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE

Variable positive airway pressure, also known as adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is indicated for patients with central sleep apnea or COPD, congestive heart failure, asthma, or other respiratory disorders. This device is similar to BiPAP in that is provides varied CPAP. The difference is that BiPAP has a preprogrammed two pressure system, while the ASV provides various air pressures in response to the patient’s pauses in breathing. This device is the newest in OSA therapies, and research is still being done. Sleep specialists are hopeful long-term studies will show not only positive outcomes for apnea hypoxia events, but also healthier cardiac function.13

COMPLIANCE ISSUES

Unfortunately, patient compliance with CPAP therapy is low. A review of 82 papers published between 1994 and 2015 found a CPAP nonadherence rate of 34.1% on average based on a 7-hour/night sleep and a nonadherence rate of 40.3% based on an 8-hour/night sleep.14

A variety of reasons may cause low compliance. Patients may feel embarrassed about needing CPAP therapy, especially as it relates to wearing a mask in front of their partners.15 CPAP can also be cumbersome and uncomfortable. Compliance is measured according to the number of hours per night and number of nights a CPAP is used. In the US, compliance has been “arbitrarily defined as usage for more than 4 hours per night for more than 70% of nights.”11,16 The more a patient uses the positive airway pressure device, the better the outcomes.11 Research demonstrated that compliance of ≥ 6 hours per night significantly improved memory and daytime sleepiness.17

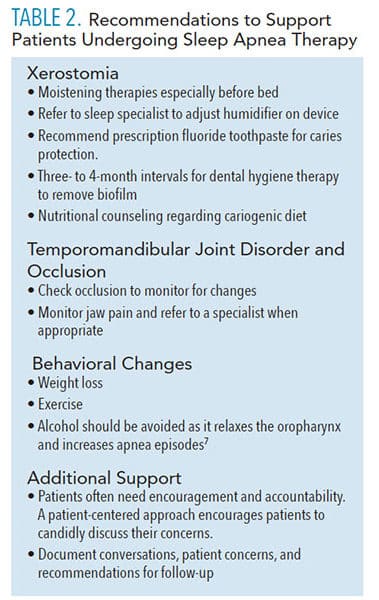

Dental hygienists can help encourage patients to seek out solutions to any problems (eg, dry mouth, and nose/pressure settings that are too high) that arise with CPAP therapy.11,18 They are well versed in the many oral therapies for xerostomia. Patients should also be encouraged to ask their sleep specialists about humidifier modifications and pressure setting issues.18

In addition, sleep problems, dermatitis, rhinitis, feelings of claustrophobia, and congestion are side effects of OSA.11 Left untreated, OSA can lead to hypertension, stroke, and cardiovascular diseases. OSA is also associated with type 2 diabetes, depression, occupational accidents, and obesity.2,19 Disruption of sleep caused by OSA contributes to behavioral changes and metabolic, and/or hormonal fluctuations that contribute to weight gain and/or inability to lose weight (Figure 1).19 Patients who are not compliant with treatment may be unaware of the seriousness of OSA and/or do not have a support system in place to address these concerns.1,20,21

OSA may also have oral health implications. A systematic review observed a relationship between reduced sleep associated with OSA and periodontitis.22 Some researchers correlate this relationship to higher levels of inflammatory cytokines due to interrupted sleep.23,24 Additionally, some OSA therapies use positive air pressure to open collapsed airways, which may result in xerostomia and increased caries risk.6

Untreated OSA also has negative personal and professional consequences.25 A pilot study of patients’ perspectives during sleep apnea treatment found patients may experience decreased work efficiency due to inability to stay awake and decreased attention span.25 Personal concerns include mood swings and negative effects on social life and relationships. A high number of patients diagnosed with OSA also experience depression. A study of 793 patients diagnosed with mild OSA found that 46.2% reported symptoms of depression.26 A literature review demonstrated an association between OSA and depression, but the exact relationship is unclear.27

A few studies suggest men have better adherence to CPAP therapy than women, and that committed relationships seem to positively correlate with improved compliance.20,21,28 Single patients also achieve good adherence with high levels of support from other sources.28 Table 2 provides recommendations to support patients with treatment compliance. Regardless of the type of therapy, positive airway pressure treatment will not meet every patient’s needs. Because of low adherence to positive airway pressure therapy, other devices have been developed, such as the anterior mandibular positioner (AMP) and hypoglossal nerve stimulation surgery.

An AMP appliance is small and sits inside the mouth like a retainer, making it much easier for some patients to sleep with comfortably.29 Patients presenting with mild to moderate OSA (more snoring, less apnea episodes, less daytime sleepiness) or those experiencing 5 AHI to 30 AHI events per hour of sleep, may find an AMP device less cumbersome.29

Hypoglossal nerve stimulation surgery involves implanting a device in the chest that tracks a patient’s breathing patterns. When it recognizes the patient is experiencing sleep cessation, it sends a signal to the hypoglossal nerve, which then causes certain muscles of the tongue to stiffen. The engagement of the muscles pulls the previously relaxed tongue out of the path of the airway.30 This therapy is still relatively new and only recommended for patients with severe OSA who do not respond to other forms of treatment. More research is needed on both of these therapies to determine efficacy.

![Sleep apnea therapy]() PATIENT CARE

PATIENT CARE

The care of patients undergoing OSA treatment has experienced a significant shift since the 1980s when CPAP therapy was first introduced. The standard of care no longer hinges on physician-made treatment decisions with little or no input from patients and a lack of aftercare once therapy was implemented. OSA management is shifting toward patient-centered care that considers individual needs and values.31 Recent research demonstrated positive outcomes with patient-centered care when providing educational, behavioral, and supportive interventions to improve adherence to positive airway pressure therapy.31

Today, patients have access to a plethora of online medical information, electronic medical records, and mobile phone apps. Many positive airway pressure devices can transfer information to an app or cloud database, which then provides patients and health care providers with access to the data.31 Hours of use, number of hypoxic episodes per hour, and quality of air mask seal are just some of the data recorded. Patients, especially those with moderate to severe OSA, may find incentive to continue positive airway pressure therapy when data show a marked decrease in apneic events per hour. Another resource, AWAKE (alert, well, and keeping energetic)—sponsored by the American Sleep Apnea Association—provides a community of support that includes discussion forms, opportunities to participate in research, and links for additional information.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals need to obtain a solid understanding of OSA and its treatment options in order to best support patients undergoing positive airway pressure therapy in hopes of increasing compliance. Education for both dental hygienists and patients is the first step in guiding patients to optimal overall health. Patients achieve better compliance when they receive support. Dental hygienists often develop relationships with their patients, and, as such, can be part of the support system to help patients achieve the best possible outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006–1014.

- American Sleep Apnea Association. Sleep Apnea Information for Clinicians. Available at: sleepapnea.org/learn/sleep-apnea-information-clinicians/. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- Smith HA, Smith ML. The role of dentists and primary care physicians in the care of patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Front Public Health. 2017;5:137.

- Collins-Kornegay E, Brame JL. Obstructive sleep apnea and the role of dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2015;89:286–292.

- Glueckert K, Jackson SJ, O’Kelly-Wetmore A, Snover, R. Obstructive sleep educational intervention of dental hygiene students. Available at: semanticscholar.org/paper/Obstructive-Sleep-Apnea-Educational-Intervention-of-Glueckert-RDH/1e17ba06610e1ecf34b7b980f252af4412948ce4. Accessed November 21, 2019.

- Magliocca KR, Helman, JI. Obstructive sleep apnea: diagnosis, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1121–1129

- Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al. Clinic guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263–276.

- de Zambottie M, Baker FC, Colrain IM. Validation of sleep-tracking technology compared with polysomnography in adolescents. Sleep. 2015;38:1461–1468.

- Bianchi MT, Goparaju B. Potential underestimation of sleep apnea severity by at-home kits: rescoring in-laboratory polysomnography without sleep staging. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:551–555.

- Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:737–747.

- Virk JS, Kotecha B. When continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) fails. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:E1112–E1121.

- Stasche N. Selective indication for positive airway pressure (PAP) in sleep-related breathing disorders with obstruction. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg.2006;5:06.

- Muza RT. Central sleep apnoea: a clinical review. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:930–937.

- Rotenberg BW, Murariu D, Pang KP. Trends in CPAP adherence over twenty years of data collection: a flattened curve. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;45:43.

- Luyster FS, Dunbar-Jacob J, Aloia MS, Martire LM, Buysse DJ, Strollo PJ. Patient and partner experiences with obstructive sleep apnea and CPAP treatment: a qualitative analysis. Behav Sleep Med. 2016;14:67–84.

- Salepci B, Caglayan B, Kiral N, et al. CPAP adherence of patient with obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Care. 2013;58:1467–1473.

- Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30:711–719.

- Mayo Clinic. CPAP Machines: Tips for Avoiding 10 Common Problems. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sleep-apnea/in-depth/cpap/art-20044164. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- Gonzaga C, Bertolami A, Bertolami M, Amodeo C, Calhoun D. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29:707–712.

- Joo MJ, Herdegen JJ. Sleep apnea in an urban public hospital: assessment of severity and treatment adherence. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;:285–288.

- Woehrle H, Ficker, JH, Graml A. Telemedicine-based proactive patient management during positive airway pressure therapy: Impact on therapy termination rate. Somnologie. 2017;21:121–127.

- Malaiappan S, Abraham C. Association between sleep and periodontitis: a systematic review. Res J Pharm Technol. 201912:2506–2510.

- Keller JJ, Wu C, Chen Y, Lin H. Association between obstructive sleep apnoea and chronic periodontitis: a population based study. J Clin Periodontal. 2013;40:111–118.

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. Sleep disturbance, sleep duration, and inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies and experimental sleep deprivation. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:40–52.

- Rudolph MA, Rotsides JM, Zapanta, PE. The patient’s perioperative perspective during the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a pilot study. Sleep Breath. 2018;22:997–1003.

- Lee W, Lee S, Ryu, H, Chung Y, Kim WS. Quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: Relationship with daytime sleepiness, sleep quality, depression, and apnea severity. Chron Respir Dis. 2016;13:33–39.

- Ejaz SM, Khawaja IS, Bhatia, S. Hurwitz, TD. Obstructive sleep apnea and depression: a review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8:17–25.

- Baron KG, Gunn HE, Wolfe LF, Zee PC. Relationships and CPAP adherence among women with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Sci Pract. 2017;1:2–8.

- Bennett LS, Davies RJO, Stradling JR. Oral appliances for the management of snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 1998;53:558–564.

- Heiser C, Benedikt H, Lozier L, Woodson BT, Startk T. Nerve monitoring-guided selective hypoglossal nerve stimulation in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:2852–2858.

- Hilbert J, Yaggi HK. Patient-centered care in obstructive sleep apnea: a vision for the future. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;37:138–147.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2019;17(11):36–39.

PATIENT CARE

PATIENT CARE