The Third Molar Extraction Conundrum

With a lack of evidence demonstrating the need to extract asymptomatic third molars, this decision must consider patient preference, clinical expertise, and mitigating factors.

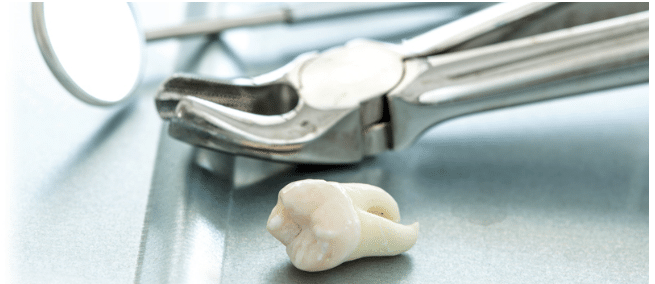

Despite the risks associated with surgical dental procedures, an abundance of healthy, asymptomatic third molars (wisdom teeth) are extracted each year. Evidence that supports the routine prophylactic extraction of wisdom teeth is surprisingly sparse. However, according to the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, about 85% of third molars ultimately require removal because of tooth crowding, decay, impaction, or pain.1 The relationship between wisdom teeth and the crowding of the mandibular anterior teeth continues to be controversial. While it seems plausible that a wisdom tooth leaning toward the second molar may initiate movement and crowding, there is little evidence that this is, in fact, the case.

Wisdom teeth are the last to erupt and commonly do so between the ages of 17 and 25. They do not completely erupt due to myriad reasons, such as insufficient room to grow in the jaw, normal functional position for eruption is not possible, or completion of root growth is fully ingrained. These scenarios may occur due to inadequate space in the jaw, obstruction by another tooth, or development in an abnormal position. Impaction of wisdom teeth occurs most frequently in the mandible and may lead to caries, periodontal diseases, and external root resorption.2,3

Eruption of third molars is determined by the following:4

- Angle at which the tooth sits

- Stage of root formation

- Extent of impaction

- Room for eruption

- Size of the third molar itself

Patients often experience no pain or discomfort from impacted third molars. In these cases, the third molar is noted as trouble-free or asymptomatic.2 Nevertheless, according to the American Dental Association, the third molars may begin to form obliquely and erupt partially or remain completely captured under the gingiva and bone.5 The presence of these third molars may cause the following complications:5–10

- Pain/discomfort

- Edematous, erythematous, tender and bleeding gingiva

- Inflammation around the jaw

- Oral malodor

- Unpleasant taste in the mouth near the affected area

- Headache or jaw ache

- Trismus, lockjaw, and occasional difficulty opening the mouth

- Occasional swollen lymph nodes in the neck

![Third Molars Classification System]()

FIGURE 1. Examples of classification systems of third molars.11

CLASSIFICATION OF IMPACTED THIRD MOLARS

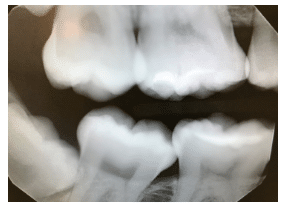

A number of third molar classification systems are available, including the two most common: Winter’s Classification and Pell & Gregory Classification systems (Figure 1).11 Both methodically aid in assessing the precise third molar positioning for observation, classification, and, if necessary, extraction. All third molars are classified as developing, erupting, embedded, or impacted. Third molars can develop until age 25, with 50% of root formation completed by age 16 and 95% of all teeth fully erupted by age 25.4However, tooth movement can continue beyond age 25.4 Figure 2 provides a radiographic example of impacted wisdom teeth.

TO REMOVE OR NOT TO REMOVE

One of the most hotly debated theories regarding the impaction of third molars is that it causes tooth movement by exerting pressure on other teeth during eruption.4 If true, this complication would increase the crowding and rotation of anterior teeth over time.12

In 1961, Leroy Vego, DDS, an orthodontist, published one of the first articles on this controversial topic: “A Longitudinal Study of Mandibular Arch Perimeter,” which examined the role of third molars on mandibular incisor crowding.13 Vego evaluated plaster stone models of 65 patients who had never undergone orthodontic treatment; 40 patients with mandibular third molars present; and 25 patients with mandibular third molars congenitally absent (over 6 years from ages 13 to 19).13 He reported that a significantly greater degree of crowding was present in those patients with third molars. Vego concluded that “the erupting lower third molar can exert a force on approximating teeth.”13

On the other hand, a 2012 randomized controlled trial with 164 participants compared the effect of extraction with retention of asymptomatic, disease-free impacted wisdom teeth on changes in the dental arch after 5 years.2 Participants had previously undergone orthodontic treatment and had crowded third molars. No evidence was found that suggested the removal of asymptomatic, disease-free impacted wisdom teeth made clinically significant changes in the dental arch.2

Today, it is widely accepted that there is not enough available evidence to determine whether third molars should be removed or not, or if they, in fact, cause mandibular crowding. When determining whether third molars should be removed, patient preferences and values are important considerations, as are clinical expertise and the risk-to-benefit ratio.14

THE ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

For patients who decide not to have their third molars extracted, proper oral hygiene is of the utmost importance. Caring for partially erupted molars can be highly challenging due to their location, especially those that are impacted and the risk of dental caries is elevated. Some third molars may have an operculum (soft tissue covering a partially erupted tooth)—impeding oral hygiene, causing irritation, and encouraging food impaction. If brushing wisdom teeth with a regular toothbrush is too difficult, clinicians can recommend a small solo brush or children’s brush to better access the third molar teeth. In addition to brushing, using a fluoride mouthrinse can be helpful and provide lavage. Rinsing with warm salt water (1⁄2 teaspoon salt in 8 oz of water) should reduce minor irritation. Clinical assessment at regular intervals is advisable to prevent any issues, such as pericoronitis, root resorption, cyst formation, tumor formation, or inflammation/infection.15

CONCLUSION

More evidence is needed to determine whether the removal of asymptomatic, disease-free impacted wisdom teeth lead to clinically significant changes in the dental arch. The dentition does acquire a natural mesial drift through the aging process, regardless of retention or extraction.

Older studies indicate that impacted wisdom teeth do, indeed, cause mandibular anterior crowding.16–18 More recent literature reviews show quite the opposite.2,19–21 They suggest that although wisdom teeth may play a small role in tooth movement in late adolescence and later, they are not the main cause and several other more important factors, such as residual growth, must be considered.2,19 Furthermore, when third molars are extracted, it is still common to see mesial shifting during the aging process.

According to Normando,22 it is unjustifiable to extract third molars only to prevent nonessential dental movement. Extracting asymptomatic third molars will not prevent lower anterior dental crowding,23 but this doesn’t mean that extracting third molars is never indicated.

Patient values and preferences should play a prominent role in deciding whether asymptomatic, disease-free impacted wisdom teeth should be removed. As Mercier and Precious12 wrote in the International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, “A strong indication for removal of an impacted third molar should be complemented with a strong contraindication to its retention.”

REFERENCES

- American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. The Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, A Patient’s Guide. Available at: aaoms.org/images/uploads/pdfs/omspip.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2018.

- Fisher EL, Garaas R, Blakey GH, et al. Changes over time in the prevalence of caries experience or periodontal pathology on third molars in young adults. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1016–1022.

- Fisher EL, Moss KL, Offenbacher S, Beck JD, White RP Jr. Third molar caries experience in middle-aged and older Americans: a prevalence study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:634–640.

- Juodzbalys G, Daugela P. Mandibular third molar impaction: review of literature and a proposal of a classification. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2013;4:e1.

- American Dental Association. Wisdom Teeth. Available at: mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/w/wisdom-teeth. Accessed April 19, 2018.

- Eng R. Third molar surgery: a review of current controversies in prophylactic removal of wisdom teeth. Available at: oralhealthgroup.com/features/third-molar-surgery-a-review-of-current-controversies-in-prophylactic-removal-of-wisdom-teeth/. Accessed April 19, 2018.

- Salamon M. Impacted wisdom teeth: oral surgery and extraction. Available at: livescience.com/34755-impacted-wisdom-teeth-removal-oral-surgery.html. Accessed April 19, 2018.

- Mettes TD, Ghaeminia H, Nienhuijs ME, Perry J, van der Sanden WJ, Plasschaert A. Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD003879.

- Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Moss KL, Barros S, Mendoza L, White RP Jr. What are the local and systemic implications of third molar retention? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(9 Suppl 1):S58–S65.

- Renton T, Al-Haboubi M, Pau A, Shepherd J, Gallagher JE. What has been the united kingdom’s experience with retention of third molars? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(Suppl 1):48–57.

- Hupp JR. Principles of management of impacted teeth. In: Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR, eds. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 6th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2014:143–167.

- Mercier P, Precious D. Risk and benefits of removal of impacted third molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;21:17–27.

- Vego L. A longitudinal study of mandibular arch perimeter. Available at: angle.org/doi/abs/10.1043/00033219%281962%29032%3C0187%3AALSOMA%3E2.0.CO%3B2?code=angf-site. Accessed April 19, 2018.

- Dodson TB. The management of the asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom tooth: removal versus retention. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20:169–176.

- Ghaeminia H, Perry J, Nienhuijs ME, et al. Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic disease-free impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD003879.

- Little RM, Riedel RA, Artun J. An evaluation of changes in mandibular anterior alignment from 10 to 20 years postretention. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;93:423–428.

- Richardson ME. The role of the third molar in the cause of late lower arch crowding: a review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;95:79–83.

- Vasir NS, Robinson RJ. The mandibular third molar and late crowding of the mandibular incisors—a review. Br J Orthod. 1991;18:59–66.

- Stanaitytė R, Trakinienė G, Gervickas A. Do wisdom teeth induce lower anterior teeth crowding? A systematic literature review. Stomatologija. 2014;16:15–18.

- Saber AM, Altoukhi DH, Horaib MF, El-Housseiny AA, Alamoudi NM, Sabbagh HJ. Consequences of early extraction of compromised first permanent molar: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2018;5;18:59.

- Genest-Beucher S, Graillon N, Bruneau S, Benzaquen M, Guyot L. Does mandibular third molar have an impact on dental mandibular anterior crowding? A literature review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. March 20, 2018. Epub ahead of print.

- Normando D. Third molars: to extract or not to extract? Dental Press J Orthod. 2015;20:17–18.

- American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Management of Third Molar Teeth. Available at: aaoms.org/docs/govt_affairs/advocacy_ white_papers/management_third_molar_white_paper.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2018.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2018;16(5):30,32-33.