THECRIMSONRIBBON/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

THECRIMSONRIBBON/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

The Therapeutic Potential of Medical Marijuana

Providing patients with scientific information and clarifying misinformation about cannabis are essential to the provision of safe, ethical, and compassionate care.

This course was published in the May 2017 issue and expires May 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the history and current legal landscape of marijuana use.

- Explain the science behind its effects on the human body.

- Identify approved and investigational cannabinoid-based drugs and their therapeutic applications and adverse effects.

- List the diseases manageable with medical marijuana and related considerations for oral health professionals.

Marijuana is classified by the United States Controlled Substances Act as a schedule I controlled substance, which means it is noted as having high abuse potential, no accepted medical use, and lacking any level of safety for use. However, many purport the medical benefits of marijuana use, and it has gained wide public acceptance. While cannabis remains illegal in the US according to federal law,1 26 states and the District of Columbia have approved the medical use of marijuana. Seven states and the District of Columbia allow recreational cannabis use.1 There is evidence of effectiveness of cannabinoid-based drugs and plant-derived cannabis in the management of cancer, human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and chronic pain.2,3 Further therapeutic potential in many other diseases and conditions explains the broad support for ongoing investigation and use by the medical community.4 Oral health professionals may expect an increase in the number of patients reporting medical or recreational cannabis use. Therefore, they should be prepared to evaluate adverse oral effects; provide counseling, education, and referrals; and ensure safe treatment outcomes while maintaining an ethical and compassionate professional approach.

Marijuana is mainly derived from two plant species: Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica.5The three most commonly used plant extracts are marijuana, derived from the dried leaves and flowers; hashish, a resin extract of the flower head; and hash oil, a concentrated fluid from hashish. These extracts differ in their potency based on the percentage of the active ingredient, delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). As plant-derived cannabis products are illegal under current federal law, they have not been regulated and evaluated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), resulting in great variability of potency and purity.6,7 This can result in potential legal liability for providers, in addition to raising the issues of abuse and addiction, unknown medical and psychiatric risks, and drug interactions.

Marijuana contains more than 100 cannabinoids, as well as 400 chemicals including aromatic hydrocarbons, benzopyrene, and nitrosamines, which, when released in cannabis smoke, can be carcinogenic.8 Cannabinoids are chemical compounds that can bind to cannabinoid receptors found in many tissues and organs. They include phytocannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids, and endocannabinoids. The two main phytocannabinoids are THC and cannabidiol (CBD). In addition to being responsible for the psychoactive properties of marijuana, THC has analgesic, anti-emetic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects, while CBD has anxiolytic, antipsychotic, and anticonvulsive properties.9 These compounds can bind to the cannabinoid receptors located in tissues and organs, including the central nervous system, peripheral neurons, immune cells, heart, lungs, and endocrine tissue.9

CANNABINOID-BASED DRUGS

Unlike the endocannabinoids produced in the human body and the plant-derived phytocannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids are compounds produced in the laboratory that can bind to the cannabinoid receptors.10 Two of the cannabinoid-based synthetic THC drugs—dronabinol and nabilone—have been approved by the FDA since 1985 as Schedule III and Schedule II drugs, respectively. As such, these drugs are not restricted, other than special precautions due to their scheduling, and can be prescribed by medical and oral health providers in the US within their scope of practice.

Dronabinol, available in several strengths as a capsule and a liquid preparation, can improve appetite loss associated with HIV/AIDS, and may also be prescribed for severe nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy. It has also been studied for muscle spasticity and pain associated with multiple sclerosis and paraplegia.11 Nabilone is FDA-approved for nausea and vomiting due to cancer chemotherapy, and has been studied for chronic pain, sleep therapy, and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis.11,12Both drugs are effective in reducing nausea and vomiting and for appetite stimulation, but are usually prescribed only if first-line anti-emetics have not been successful, due to more frequent short-term adverse effects.11 Dronabinol and nabilone are sometimes used adjunctively with traditional therapies, and may be appropriately prescribed for FDA-approved and off-label uses for which sufficient evidence is available.2

A number of other synthetic cannabinoid-based drugs are under investigation and/or in clinical trials for previously described conditions and for other indications, such as brain injury and anti-tumor properties (dexanabinol) and multiple sclerosis-related spasticity, scleroderma fibrosis, and arthritic pain (ajulemic acid).13

The most common adverse effects associated with orally ingested dronabinol and nabilone are dizziness, sedation, “feeling high,” and dysphoria (uneasiness). Patients may prefer the cannabinoid-based drugs to a first-line anti-emetic, such as procholperazine, despite more frequently reported side effects.12

BOTANICAL CANNABINOIDS

No plant-based cannabinoids are approved in the US, but nabiximols—approved in more than 20 countries—has fast-track designation by the FDA and is in Phase III clinical trials.14 Nabiximols is effective in reducing symptoms of muscle spasticity, pain, and overactive bladder in patients with multiple sclerosis and for neuropathic pain associated with other conditions.2 Additionally, improvement of activities of daily living and quality of life measures were noted in several published trials.14

Nabiximols—an equal mixture of THC and CBD—is of particular interest to oral health professionals. It is delivered as an oral mucosal spray to the buccal and sublingual tissues. Besides common initial adverse effects of dizziness, sleepiness, unsteadiness, taste changes, burning oral mucosal ulcerations, and reversible lesions appearing as white patches or reddened irritations can occur at the site of administration (Figure 1).15 Patients are advised to rotate the area of application to avoid this effect. Notably, long-term use (several months) of nabiximols spray has not been associated with drug tolerance, abuse, or withdrawal symptoms.14

A proprietary formulation of plant-derived pure CBD is in clinical trials for the treatment of several severe infant-onset epilepsy disorders. This CBD extract in an elixir form was given fast-track, as well as orphan drug status by the FDA in 2014, indicating its potential use for rare, but life threatening conditions that have been previously drug and treatment resistant. These include Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex, and infantile spasms. Results of controlled studies have shown 39% to 44% reductions in monthly seizures, and a favorable safety profile.16 CBD does not cause the psychotropic effects of THC—which is key, considering that the target population is predominantly children.

Based on these study results and safety profile, and the serious and life-threatening nature of the indications, this proprietary formulation of CBD is also available to patients through the FDA-authorized, independent, physician-led “Expanded Access” program, also known as “compassionate use.”17–19 Reduction in monthly seizures for patients enrolled in this program was 45% to 71%.18,19This FDA program considers the ethics of allowing access to drugs outside of randomized controlled trials for those who have no other recourse with regard to effective drugs and therapies.17

MEDICAL MARIJUANA

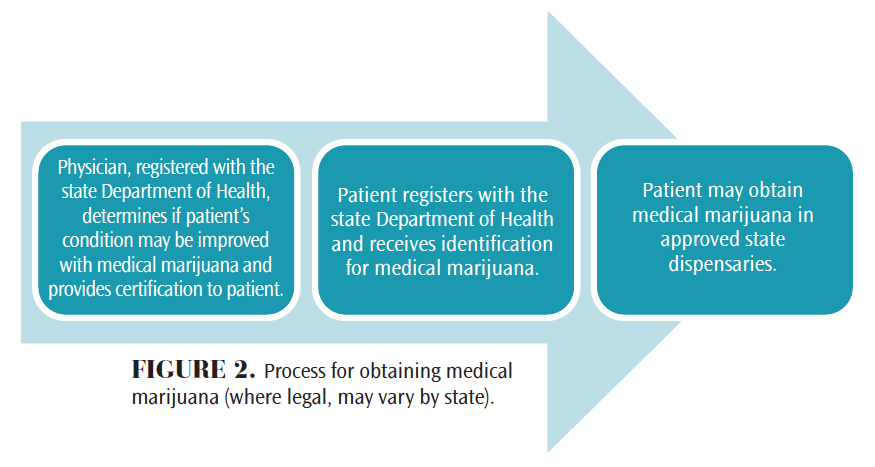

Medical marijuana treatments that involve plant-based substances in variable administration routes (smoking, vaporization, pills, topical application, and others) have not been approved by the FDA and are illegal under federal law even though some states have legalized medical use. As such, it is illegal for providers to prescribe medical marijuana, but they can recommend and authorize its use for their patients as part of protected provider-patient communication in states where medical marijuana use is allowed.20 Figure 2 demonstrates the approximate state-regulated process for obtaining medical marijuana.

For any treatment, including medical marijuana, the most crucial questions for patients and providers are: how effective it is for the condition being treated, and what are the short- and long-term adverse effects? To provide the most comprehensive in-depth review of the available evidence regarding marijuana use and its health effects, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a report in 2017 that summarized what is known about the therapeutic effects of marijuana in the management of various diseases/conditions.2 Also examined were the relationship between marijuana and cancer, cardio-metabolic risk, respiratory disease, immunity, injury, and death. The most substantial evidence of therapeutic effects of cannabis or cannabinoids (including approved oral cannabinoid-based drugs discussed above) is in treatment of chronic pain in adults, as anti-emetics in treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and in improving multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms. There is also moderate evidence of cannabis/cannabinoids effectiveness in improving sleep in individuals with sleep disturbance associated with several conditions (chronic pain, fibromyalgia, and others). For many other diseases/conditions under active investigation, including HIV/AIDS, Tourette syndrome, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), epilepsy, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, depression, traumatic brain injury, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), there is limited or insufficient evidence because findings are based on small-scale, short-duration studies—in some cases without proper control groups. The committee highlighted the need for research of therapeutic effects of cannabis/cannabinoids in these diseases, especially PTSD and epilepsy, as a significant number of patients are using cannabis for management of these conditions.2

Other, less studied but potentially important effects of cannabis/cannabinoids include their anti-tumoral properties demonstrated in the preclinical studies of several cancers. While more evidence from clinical studies, which are underway for glioma, is needed, it was demonstrated that THC can be safely injected intratumorally.20 With their better tolerability profiles than currently available chemotherapeutics, if shown effective as anti-neoplastic agents, cannabinoid-based drugs may open a new frontier in cancer treatment. Additionally, their ability to modulate the immune system by binding to the CBD receptors located on the immune cells, prompted rigorous investigations into the effects of cannabinoids in autoimmune diseases/conditions associated with inflammation. In animal and human studies, cannabinoids have shown immunosuppressive effect, with potential applications in MS, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), and neuropathic pain.21

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Adverse effects of cannabis, including synthetic and plant-based cannabinoids in various forms of administration (oral, topical, inhalation), were summarized in a 2015 systematic review published by the Journal of the American Medical Association.11 Notably, this extensive analysis focused exclusively on medical marijuana. The most common short-term adverse effects were dizziness, dry mouth, nausea/vomiting, fatigue/drowsiness, disorientation, euphoria, and hallucinations. Importantly, fatal overdose with cannabis alone has not been reported.6 Possible long-term effects, including association with cancers of the head and neck, lungs, and esophagus, are especially concerning with the use of smoked cannabis. Although cannabis use is associated with cigarette smoking and, like tobacco smoke, cannabis smoke contains carcinogens, there is no evidence of its association with head and neck and lung cancers, while evidence regarding esophageal cancer is insufficient.2 Further studies should address the risk factors associated with cannabis use and specific types of cancers based on their origin and histological and molecular characteristics.2 Based on the known adverse effects and properties of marijuana, it should be used with caution in patients with psychiatric, cardiovascular, respiratory, and immunologic diseases.13

ORAL CONSIDERATIONS

Cannabis-induced oral adverse effects have been assessed in a limited number of well-controlled studies and reviews,8 and those associated specifically with medical applications are few. Most did not assess effects other than xerostomia,11,13 a common complaint in both recreational and medical users. Although smoked cannabis is more likely to cause dry mouth and throat, the anticholinergic effects of cannabis have been documented8 and may be associated with frequent use in other dose forms. Dental caries risk is increased due to lack of saliva and is associated with poor oral hygiene in frequent recreational users, who appear to have increased appetite and a preference for sweet foods.5,15,22

Oral mucosal changes include the unique occurrence of white patches associated with the nabiximols oral spray (Figure 1),15 and leukoedema, long associated with smoking and other mucosal irritants, occurs more frequently in cannabis users than nonsmokers. Although cannabis smoke contains many compounds, including known carcinogens, no evidence to date indicates increased risk for oral squamous cell carcinoma.2,5,8 A documented increase in the prevalence of Candida albicans infections is possibly associated with immunosuppressive effects of cannabis, and the microorganism’s affinity for hydrocarbons present in cannabis smoke.23 There is some evidence of increased risk of periodontitis in young users of cannabis when compared to nonsmokers,22 but it has been generally attributed to poor plaque control and reduced protective salivary flow.5 In heavy recreational users, uvulitis, gingival enlargement, gingivitis, and alveolar bone loss have been reported.7,23

Knowledge of the scientific basis for medical cannabis- and cannabinoid-based drugs, as well as treatment implications and adverse effects of medicinal and recreational use, is essential when providing health care to the growing number of patients who use them. Comprehensive assessment of medical history, concurrent medications, vital signs, and investigation of the use and effects of specific cannabinoid agents is paramount. Evaluation of possible cognitive impairment that may interfere with valid informed consent is an ethical and legal responsibility.7 However, the decision to proceed with planned treatment should be based on the objective assessment and not merely on the patient’s report of cannabis use, whether historical or recent, medical, or recreational. Physiological and psychoactive action of cannabis depends on the form, amount/concentration, and route of administration,13 so reviewing this information with patients is essential. This conversation should be done in a nonjudgmental way to ensure patients’ trust, openness, and compliance. Postponement of treatment, if possible and necessary to ensure successful outcomes, should be thoroughly explained and documented. Patients should never feel that they are being punished for their honest disclosure of cannabis use by being re-scheduled or denied treatment.7

CONCLUSION

A review of the scientific evidence calls for more investigation to evaluate the effectiveness and health effects of cannabinoid-based drugs and therapies. Currently, rigorous research is subject to disharmony between federal and state laws, which creates uncertainty for health care professionals and scientists who must rely on more substantial evidence. Oral health professionals face the challenge of treating patients who may be currently using some of the existing therapies, or experiencing conditions for which these drugs may potentially benefit or harm them. Additionally, providing patients with current scientific information and clarifying possible misinformation on cannabis is essential in the performance of safe, ethical, and compassionate treatment.

References

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA and Marijuana: Questions and Answers. Available at:fda.gov/newsevents/publichealthfocus/ucm421168.htm. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC:National Academies Press; 2017.

- Adler JN, Colbert JA. Clinical decisions. Medicinal use of marijuana—polling results. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:e30.

- Compton WM, Han B, Hughes A, Jones CM, Blanco C. Use of marijuana for medical purposes among adults in the United States. JAMA. 2017;317:209–211.

- Joshi S, Ashley M. Cannabis: A joint problem for patients and the dental profession. Br Dent J. 2016;220:597–601.

- Grant I. Medical marijuana: Clearing away the smoke. Open Neurol J. 2012;6:18–25.

- Grafton SE, Huang PN, Vieira AR. Dental treatment planning considerations for patients using cannabis: a case report. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147:354–361.

- Versteeg PA, Slot DE, van der Velden U, van der Weijden GA. Effect of cannabis usage on the oral environment: a review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:315–320.

- Greydanus DE, Hawver EK, Greydanus MM, Merrick J. Marijuana: current concepts. Front Public Health. 2013;1:42.

- Kaur R, Ambwani SR, Singh S. Endocannabinoid system: a multi-facet therapeutic target. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2016;11:110–117.

- Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456–2473.

- Smith LA, Azariah F, Lavender VT, Stoner NS, Bettiol S. Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2015.

- Parmar JR, Forrest BD, Freeman RA. Medical marijuana patient counseling points for health care professionals based on trends in the medical uses, efficacy, and adverse effects of cannabis-based pharmaceutical drugs. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12:638–654.

- Vermersch P, Trojano M. Tetrahydrocannabinol: cannabidiol oromucosal spray for multiple sclerosis-related resistant spasticity in daily practice. Eur Neurol. 2016;76:216–226.

- Scully C. Cannabis; adverse effects from an oromucosal spray. BDJ. 2007;203:E12–E12.

- GW Pharmaceuticals. GW Pharmaceuticals Announces Second Positive Phase 3 Pivotal Trial for Epidiolex (cannabidiol) in the Treatment of Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. Available at: gwpharm.com/ about-us/news/gw-pharmaceuticals-announces-second-positive-phase-3-pivotal-trial-epidiolex. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Expanded Access (Compassionate Use). Available at:fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ExpandedAccessCompassionateUse/. Accessed April 18 2017.

- Devinsky W, Sullivan J, Friedman D, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Epidiolex (Cannabidiol) in Children and Young Adults with Treatment-Resistant Epilepsy: Update from the Expanded Access Program. 2015.

- Devinsky O, Marsh E, Friedman D, et al. Cannabidiol in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy: an open-label interventional trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:270–278.

- Kramer JL. Medical marijuana for cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:109–122.

- Katchan V, David P, Shoenfeld Y. Cannabinoids and autoimmune diseases: A systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:513–528.

- Shariff JA, Ahluwalia KP, Papapanou PN. Relationship between frequent recreational cannabis (marijuana and hashish) use and periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2011-12. J Periodontol. 2017;88:273–280

- Darling MR, Arendorf TM, Coldrey NA. Effect of cannabis use on oral candidal carriage. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:319–321.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2017;15(5):41-44.