The Overlooked Risk of Hearing Loss in Dental Practice

Excessive noise from dental equipment poses a significant threat to hearing health, but preventive strategies can safeguard auditory well-being and enhance workplace safety.

This course was published in the January/February 2025 issue and expires February 2028. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 770

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- List the effects of excessive noise on auditory health.

- Identify the various hearing protection devices/ear protection devices available for use by dental professionals.

- Discuss the role of the dental hygienist in noise management for the protection and maintenance of auditory health.

Dental professionals face a variety of occupational health challenges, including hearing loss. Hearing is a critical activity of daily living and its loss presents a variety of hardships from communication problems to safety concerns.

Dental professionals are exposed to noise associated with their specific work environments. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has identified work-related hearing damage as a key research priority in the dental field, along with other occupational risks.1

Implementing measures, such as engineering and administrative controls, regular audiometric testing, and the consistent use of hearing protection devices, may assist in preventing noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Hearing damage can be permanent and irreversible, but early detection and intervention, as well as education regarding work-related risks, are essential to minimize further damage.2–4

Effects of Excessive Noise

Constant exposure to noise results in both auditory and nonauditory effects. Nonauditory effects may include sleep disturbance, hypertension, decreased learning performance, interference with communication and concentration, stress reactions, mental fatigue, annoyance, and reduced efficiency. On the other hand, auditory effects may manifest as tinnitus or temporary and potentially permanent hearing loss.5

Hearing loss affects approximately 1.5 billion people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, with this number expected to increase to nearly 2.5 billion by 2050.6 Essentially, the increasing number of older adults, in which hearing loss is more common, is the cause of this jump. Other factors include increased noise exposure from various technological devices and occupational hazards to auditory health.

Sensorineural hearing loss is the most common type of hearing loss in adults.2 It is characterized by damage to the inner ear or the nerve pathways from the inner ear to the brain. The most prevalent forms of sensorineural hearing loss include age-related hearing loss due to the natural deterioration of inner ear structures (presbycusis), and NIHL. When the sensory cells in the cochlea are damaged and/or killed by prolonged exposure to loud noises, NIHL occurs.7 These cells are responsible for detecting sound vibrations and converting them into electrical signals that are transmitted to the brain. Once these cells are damaged, they do not regenerate or repair themselves. Instead, they are typically replaced by scar tissue, which leads to a permanent reduction in hearing sensitivity.8

NIHL develops steadily after prolonged or sporadic exposure to loud noise. After exposure to loud noise, individuals may experience a temporary threshold shift or temporary hearing loss for 16 to 48 hours. During the early stages of NIHL, pure tone audiometry may show normal results, and there may be no noticeable signs of hearing loss.

The term “hidden hearing loss” refers to damage or loss of synaptic connections between hair cells and cochlear neurons. This type of damage may not be detected by standard audiometric tests, yet it can still lead to difficulties in hearing in noisy environments and problems with speech understanding.3 Common symptoms of NIHL include muffled hearing, difficulty understanding or following conversations, and tinnitus.2

In addition to the direct influence on hearing, excessive noise may increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and cause stress, sleep disruption, fatigue, anxiety, depression, difficulty concentrating, and mood disorders.9,10 According to the United States National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, exposure to prolonged or continual noise levels exceeding 85 dBA (weighted scale for judging loudness that corresponds to the hearing threshold) can have detrimental effects on the human ear.11 To mitigate these effects, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recommends implementing a hearing conservation program if this exposure exceeds an 8-hour time-weighted average.12 This program aims to protect workers’ hearing through noise assessments, engineering controls, hearing protection devices, audiometric testing, and employee training. According to OSHA, approximately 30 million people experience occupational noise-induced hearing loss due to harmful noise levels in their workplaces.12

Noise in the Dental Environment

To understand how sound affects hearing, it’s important to consider frequency — measured in Hertz (Hz) — which indicates the rate at which sound waves complete one cycle. A healthy, young person typically can hear frequencies ranging from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. This range covers the spectrum of audible sound waves that can be perceived by the human auditory system under normal conditions.2 However, the ear is more sensitive to certain frequencies, making them seem louder even at the same intensity as others.

Dental professionals are regularly exposed to a variety of noises throughout the workday.2High and low-speed turbines (handpieces), amalgamators, high-volume suction devices, ultrasonic instruments, vibrators (for mixing and vibrating materials), model trimmers, and compressors are all widely used in the dental setting and the noise they emit may have deletrious effects on hearing.1,5

Ultrasonic scalers generate high-intensity ultrasonic sound typically ranging between 20 and 50 kHz4, producing sound pressure levels from 87 to 107 dBA.3 In a systematic review by Hartland et al,8 82% of the studies reported a positive association between hearing loss and dentists/dental specialists, with years of clinical experience identified as a significant risk factor. Studies conducted at two dental schools found that sound levels from dental equipment, often used together, ranged between 60 and 99 dBA and 52 to 92 dBA.13,14

The use of ultrasonic scalers is a potential contributor to temporary shifts in hearing thresholds, tinnitus, and statistically significant differences in audiometric thresholds at frequencies such as 3000 Hz. However, these instruments generate sounds at ultra-high frequencies that are often inaudible to humans.3 Another study across four dental practices revealed that ultrasonic scalers were the only equipment exceeding 85 dBA.15 A study by Chopra et al16 demonstrated that noise generated by ultrasonic scalers negatively impacts hearing acuity, particularly at low threshold frequencies. The findings specified an increase in pure tone audiometry, a standard assessment of hearing sensitivity. This increase results in a higher threshold, which can indicate a type of hearing loss. Furthermore, there were changes in the acoustic reflex threshold and reduced values in otoacoustic emissions tests, indicating alterations in the hearing threshold.16 This suggests that even short-term exposure to ultrasonic scalers can impact overall hearing acuity.

Hearing Protection

Various studies have identified dental professionals and students as being at risk for work-related hearing impairment.2,17-20 Surakanti et al19 found that 15.8% of dentists tested on pure tone audiometry tests showed hearing impairment. This was attributed to the intensity of sound and the duration of exposure in their work environment.

Veeramachineni et al18 revealed a positive correlation between years of experience and diminished hearing capacity among dental practitioners. Consequently, hearing protection is now recommended more frequently in dental offices than in the past. Despite these findings, most dental professionals do not use hearing protection devices (HPDs) or ear protection devices (EPDs).21 In addition to protecting against auditory damage, HPDs/EPDs may also reduce the risk of nonauditory effects associated with high-frequency noise exposure, such as fatigue, nausea, headaches, irritation, and hypertension.16

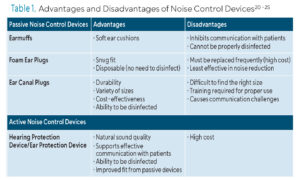

Standard protocol should be implemented to optimize efficiency when using HPDs/EPDs. Key components of effective usage include fitting and/or individual customization; providing comprehensive training on the correct use, insertion, and removal; instruction on maintenance, care, and hygiene; periodic evaluation of effectiveness through fit testing; audiometric testing to monitor any changes in hearing thresholds; and encouraging and monitoring compliance with use among.22 Perhaps the most crucial element is the selection of a suitable device. There are two main forms of HPD/EPDs: passive noise control devices and active sound control devices (Table 1).2,21-26

![]() Passive Noise Control Devices

Passive Noise Control Devices

Passive noise control devices, earmuffs, disposable foam earplugs, and ear canal plugs, function as physical barriers to sound.23 Earmuffs are constructed with sound-attenuating material and soft ear cushions, fitting over the ears with hard outer cups and a headband. Their design, however, presents challenges for dental professionals due to difficulties in communicating with patients and the impracticality of disinfecting such devices after use.24

Disposable foam earplugs, which are rolled into a thin cylinder and then inserted into the ear canal, expand to fit snugly. They are disposable, which eliminates the need for cleaning. Foam earplugs are generally the least expensive form of HPDs/EPDs; however, the cost of replacements may discourage their consistent use.21,25 While effective, foam earplugs typically provide less noise reduction compared to earmuffs. Because effective communication between the patient and clinician is important in dentistry, traditional HPDs/EPDs may not be practical for noise prevention.

Ear canal plugs come in two types: pre-molded, reusable plugs and canal caps. Ear canal plugs offer a more tailored fit compared to foam earplugs and earmuffs, potentially providing better comfort and less interference with communication.21,24 They offer the benefits of reusability, durability, variety of sizes, cost-effectiveness, and cleanability.21,24 However, it may be challenging to to find the right size and communication may be hinered with ear canal plugs.21,24

Active Noise Control Devices

Active sound control devices electronically modify sound transmission by reducing unwanted noise rather than simply blocking it.24,25 They use hearing aid batteries and offer hearing protection from high-level sounds while allowing other sounds, such as speech, to be heard.21,24

Active sound control devices electronically modify sound transmission by reducing unwanted noise rather than simply blocking it.24,25 They use hearing aid batteries and offer hearing protection from high-level sounds while allowing other sounds, such as speech, to be heard.21,24

The major benefit of electronic HPDs/EPDs is their ability to facilitate two-way communication with patients. Unlike passive HPDs, electronic models do not completely block out sound, making it easier for practitioners to hear patients during procedures. Additionally, electronic HPD/EPDs can be disinfected and they generally provide a better fit compared to passive options. However, electronic HPDs tend to be the most expensive among HPD/EPD types. The higher initial cost and ongoing expense of replacement batteries may be deterrents.21

Role of the Dental Hygienist

To encourage awareness about the risk for work-related hearing loss, more education and training needs to be provided. KU Leuven in Belgium has introduced coursework on hearing and hearing-loss prevention into its dental school curriculum.20 With sufficient knowledge, dental hygienists can assist in implementing effective measures to protect their hearing.3,20 Education that emphasizes the significance of adopting noise-reduction strategies and addresses the variability in noise levels within dental healthcare settings is essential to promoting auditory health.3

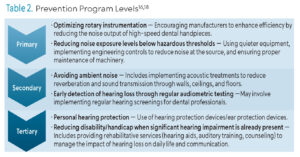

Along with the use of HPDs/EPDs, reducing the risk of occupational NIHL relies on prevention measures, as NIHL is irreversible. Studies conclude that an effective, comprehensive program should be structured around three levels of noise attenuation and prevention (Table 2).3,19 By advocating for the integration of these prevention strategies into occupational health and safety protocols, dental hygienists can effectively contribute toward mitigating the risk of NIHL.3,18,19

![]() Conclusion

Conclusion

Fostering awareness about the risks of NIHL and the benefits of using HPDs/EPDs is fundamental step in promoting a culture of hearing protection among dental professionals. Future research on assessing actual noise levels generated by dental instruments and equipment, evaluating the duration and frequency of exposure among dental personnel, and investigating the specific impacts on hearing health over time may help establish clearer guidelines and recommendations for hearing protection measures in dental workplaces.

References

- Al-Omoush SA, Abdul-Baqi KJ, Zuriekat M, Alsoleihat F, Elmanaseer WR, Jamani KD. Assessment of occupational noise-related hearing impairment among dental health personnel. J Occup Health. 2020;62:e12093.

- Henneberry K, Hilland S, Haslam SK. Are dental hygienists at risk for noise-induced hearing loss? A literature review. Can J Dent Hyg. 2021;55:110-119.

- Alberti G, Portelli D, Galletti C. Healthcare professionals and noise-generating tools: Challenging assumptions about hearing loss risk. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:6520.

- Kirchner DB, Evanson E, Dobie RA, et al. Occupational noise-induced hearing loss: ACOEM Task Force on Occupational Hearing Loss. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54:106–108.

- Anjum A, Butt SA, Abidi F. Hazards in dentistry: a review. Pakistan Journal of Medicine and Dentistry. 2019;8(4):76-81.

- World Health Organization. World Report on Hearing. Available at who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020481. Accessed November 12, 2024.

- Le TN, Straatman LV, Lea J, Westerberg B. Current insights in noise-induced hearing loss: A literature review of the underlying mechanism, pathophysiology, asymmetry, and management options. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;46:41.

- Hartland JC, Tejada G, Riedel EJ, Chen AHL, Mascarenhas O, Kroon J. Systematic review of hearing loss in dental professionals. Occup Med (Lond). 2023;73:391-397.

- Burk A, Neitzel RL. An exploratory study of noise exposures in educational and private dental clinics. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2016;13:741–749

- Ma KW, Wong HM, Mak CM. Dental environmental noise evaluation and health risk model construction to dental professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1084.

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Noise-induced hearing loss. Available at nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss. Accessed November 12, 2024.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Occupational Noise Exposure. Available at osha.gov/noise. Accessed November 12, 2024.

- Sampaio Fernandes JC, Carvalho APO, Gallas M, Vaz P, Matos PA. Noise levels in dental schools. Eur J Dent Educ 2006;10:32–37.

- Qsaibati ML, Ibrahim O. Noise levels of dental equipment used in dental college of Damascus University. Dent Res J. 2014;11:624–630.

- Setcos JC, Mahyuddin A. Noise levels encountered in dental clinical and laboratory practice. Int J Prosthodont. 1998;11:150–157.

- Chopra A, Mohan K, Guddattu V, Singh S, Upasana K. Should dentists mandatorily wear ear protection device to prevent occupational noise-induced hearing loss? A randomized case–control study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2022;12:513.

- Myers J, John AB, Kimball S, Fruits T. Prevalence of tinnitus and noise-induced hearing loss in dentists. Noise Health. 2016;18:347–354

- Veeramachineni C, Madhamshetty V, Aravelli S, Nimeshika R, Penigalapati S, Swetha K. Occupational noise-induced hearing loss among dental professionals: an in vivo study. World J Dent. 2024;15:64-67.

- Surakanti JR, Guntakandla VR, Raga P, et al. Dentist’s hub bub — a cross-sectional study on impact of long-term occupational noise exposure on hearing potential among dental practitioners. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 2021;10(43):3676-3683.

- Dierickx M, Verschraegen S, Wierinck E, Willems G, van Wieringen A. Noise disturbance and potential hearing loss due to exposure of dental equipment in Flemish dentists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5617.

- Spomer J, Estrich CG, Halpin D, Lipman RD, Araujo MWB. Clinician perceptions of 4 hearing protection devices. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2017;2:363–369.

- Kaweckyi N. Noise Exposure and PPE: Incorporating an occupational hearing loss program into your workplace. Dental Assistant. 2021;90:12-16.

- Truax B, ed. Handbook for Acoustic Ecology. 2nd ed. Somerville, Massachusetts: Cambridge Street Publishing;1999.

- Manchir M. Can you hear me now? PPR spotlights hearing protection devices for dentists. ADA News. Available at: ada.org/en/publications/adanews/2016-archive/october/can-you-hear-me-now. Accessed November 12, 2024.

- Paramashivaiah R, Prabhuji ML. Mechanized scaling with ultrasonics: Perils and proactive measures. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:423–428.

- Kadanakuppe S, Bhat PK, Jyothi C, Ramegowda C. Assessment of noise levels of the equipments used in the dental teaching institution, Bangalore. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:424–431.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January/February 2025; 23(1):28-31.