The Hidden Oral-Liver Connection

Growing evidence links periodontal diseases to the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

This course was published in the March/April 2025 issue and expires April 2028. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 490

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence and potential causes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) worldwide.

- Identify the association between NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, metabolic syndrome, and periodontitis.

- Explain the dental hygienist’s role in mitigating the progression of NAFLD through both education and therapy.

Chronic liver disease is a substantial public health concern. Historically, viral liver diseases, such as hepatitis B and hepatitis C, have been the number one causes of death due to cirrhosis or liver scarring.1 However, due to preventive measures for hepatitis B through vaccinations and newly developed treatment for hepatitis C, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is emerging as the most prevalent form of chronic liver disease.1

NAFLD is caused by excessive hepatic steatosis (fat accumulation) in the liver in individuals who do not overconsume alcohol.2 Even though NAFLD is the most common form of liver disease in the United States, many healthcare professionals have little knowledge of the disease. Conversely, the lack of public awareness about NAFLD may be linked to healthcare providers’ misunderstanding of the disease. Lifestyle changes are the most effective way to alter the course of NAFLD, so the lack of understanding and low awareness of this disease hinders the prevention of further illness.3

When NAFLD is left untreated, the disease may progress into a more severe condition called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH occurs in approximately 20% of patients with NAFLD and is associated with liver damage and cirrhosis.2 NASH is a significant factor in liver-related mortality, such as chronic liver disease and hepatic carcinomas. Recent studies have found a link between poor oral health and an increased severity of NAFLD.4-6

Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

NAFLD is estimated to affect 30% of the world’s population, and the prevalence of NAFLD is only expected to rise, paralleling the growing incidence of obesity.4,7 This upward trend increases the incidence of liver-related morbidity due to NAFLD and metabolic comorbidities associated with this disease. Research shows that being overweight as a child or adolescent is associated with the diagnosis of NAFLD earlier in adulthood.4 Consequently, liver-related morbidity is seen at a younger age. The rising number of NAFLD cases places additional strain on healthcare systems worldwide.

NAFLD, NASH symptoms, and their outcomes impair the health-related quality of life for patients with these conditions. Until effective therapies are developed to treat NAFLD, preventive measures, including reducing childhood obesity, should be paramount.

Diagnosis and Etiology

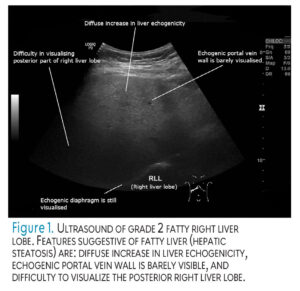

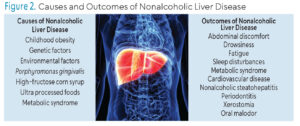

The diagnosis of NAFLD and NASH is determined using ultrasound (Figure 1), multiple laboratory tests, and a liver biopsy.2,8 Laboratory tests often examine liver enzyme levels. Alanine aminotransferase is a liver enzyme frequently elevated in patients with NASH, signifying chronic liver disease related to hepatocellular cancers and liver-related mortality.9 Symptoms of NAFLD were once considered silent until the disease progressed into liver damage; however, recent findings indicate the presence of initial, subtle symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, drowsiness, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and lack of energy (Figure 2).8

While the exact etiology of NAFLD is unknown, a bidirectional association has been established between NAFLD and metabolic syndrome (MetS), which includes obesity, high triglyceride levels, low high-density lipoprotein levels, elevated blood pressure, and higher-than-normal glucose levels.2 Individuals with MetS are at increased risk of developing NAFLD. New research has determined the risk of developing NAFLD is different between individuals, but can be established by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.10

While the exact etiology of NAFLD is unknown, a bidirectional association has been established between NAFLD and metabolic syndrome (MetS), which includes obesity, high triglyceride levels, low high-density lipoprotein levels, elevated blood pressure, and higher-than-normal glucose levels.2 Individuals with MetS are at increased risk of developing NAFLD. New research has determined the risk of developing NAFLD is different between individuals, but can be established by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.10

Genome-wide association studies have shown a strong heritability for mutations associated with an elevated chance of developing NAFLD.10 Having a parent with NAFLD is considered a major independent risk factor for developing the disease later in life. Supporting the heritability of these mutations are studies reporting a stronger correlation of NAFLD occurring in monozygotic (identical) twins compared to dizygotic (fraternal) twins.10 Several genetic mutations and variations lead to an increased risk of NAFLD.11-13

Individuals with NAFLD have an increased overall yearly mortality rate of 17.05 per 1,000 compared to those without NAFLD.7 Cardiovascular disease is the most reported cause of death associated with NAFLD, followed by liver-related diseases such as fibrosis, cirrhosis, and cancer.2,7 Once NAFLD progresses to NASH, it is the second most common reason for liver transplant, following hepatitis C. NASH is expected to take over as the most common reason for liver transplant due to the growing prevalence of NAFLD and because newly developed treatments for hepatitis C are proving successful.2

Individuals with NAFLD have an increased overall yearly mortality rate of 17.05 per 1,000 compared to those without NAFLD.7 Cardiovascular disease is the most reported cause of death associated with NAFLD, followed by liver-related diseases such as fibrosis, cirrhosis, and cancer.2,7 Once NAFLD progresses to NASH, it is the second most common reason for liver transplant, following hepatitis C. NASH is expected to take over as the most common reason for liver transplant due to the growing prevalence of NAFLD and because newly developed treatments for hepatitis C are proving successful.2

Treatment

The epigenetic interactions associated with NAFLD shed light upon the disease and are an important factor in determining risk prediction and medication development.14 Currently, no United States Food and Drug Administration-approved medications are available to treat NAFLD, but several are in the evalutableation phase. Insulin sensitizers, antioxidants, and cholesterol-lowering medications may have promising applications for NAFLD treatment.8 Patients with NAFLD are more likely to be on medications to treat the comorbidities associated with this disease, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and high blood pressure.2 A healthy lifestyle, including a nutritious Mediterranean diet and physical exercise, are beneficial preventive interventions for NAFLD. These lifestyle changes are also recommended as early treatment of NAFLD and NASH.2,4,15

Oral Manifestations

Recent studies have made the connection between oral conditions and liver disease.6,9,16,17 These connections could potentially be explained by the shared risk factors of NAFLD to other comorbidities; however, the oral-liver link is not merely a consequence of shared risk factors but may be due directly to oral infection-induced liver injury.6

Not only is NAFLD affected by the immune response generated by periodontitis, but as liver disease progresses, it can affect oral health. Xerostomia is common among patients with liver disease and is a known risk factor for caries, oral mucosal lesions, and periodontitis.6

Studies show a strong relationship between periodontitis and NAFLD.18 A systematic review comprising 12 studies and 53,384 patients was conducted in 2018.18 Eleven studies showed periodontitis is a risk factor for NAFLD progression, and a statistically significant correlation between periodontal diseases and NAFLD exists. Periodontitis is caused by an overzealous immune response to oral bacteria in biofilm and results in the breakdown of the supporting structures of the periodontium, including the soft tissues and supporting bone.

Oral pathogens and the induced inflammatory responses are not confined to the oral cavity and, if left untreated, can spread through the body. Systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, rheumatoid arthritis, and MetS have also been linked to periodontal diseases, indicating the harmful systemic inflammation periodontitis generates.18 Additionally, many of the diseases associated with MetS have been linked to NAFLD.2

Porphyromonas gingivalis initiates a variety of host responses and an association exists between the endotoxins produced by P. gingivalis and NASH-induced inflammation along with fibrosis.17,18 A study of individuals with NAFLD was conducted to identify whether P. gingivalis is associated with NAFLD pathology related to liver stiffness. Liver stiffness is a measure of how resistant the liver is to deformation, which indicates the presence of scar tissue. Study participants underwent liver stiffness exams, hematological tests, periodontal examinations, and saliva collection.19 The study found a relationship between NAFLD pathology and periodontal diseases with three conclusions. First, the group with a higher concentration of P. gingivalis in their saliva had an increased incidence of liver stiffness than the group with a lower saliva concentration. Second, individuals with increased liver stiffness had elevated P. gingivalis serum antibody levels. There was evidence that P. gingivalis infections create lipopolysaccharides, cytokines, and endotoxins involved with systemic inflammation, which are also associated with liver stiffness. Lastly, the study showed greater liver stiffness in individuals with more than 10 periodontal pockets measuring greater than 4 mm.

One theory concerning the oral link to NAFLD is the possible liver exposure to these oral pathogens, their endotoxins, and inflammatory markers through microulcerations in the periodontal pocket, which is then directed to the liver through the systemic circulation.17 Nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) may be a promising strategy to combat NAFLD.9,17

Another hypothesis is the correlation of gut microbial dysbiosis to liver inflammation. Dysbiosis in the stomach and intestines occurs as an individual swallows P. gingivalis and other oral pathogens, which then harm the gut barrier by initiating bacterial overgrowth, outcompeting commensal organisms, changing bacterial metabolites, and increasing gut permeability.16,17

Role of the Dental Hygienist

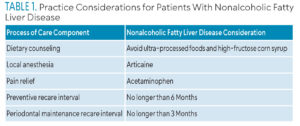

The effectiveness of oral disease prevention and periodontal disease treatment relies on appropriate oral self-care education, dental hygiene diagnosis, and individualized dental hygiene care planning. Table 1 provides a summary of treatment considerations.

One approach to preventing and treating NAFLD is managing oral pathogens with NSPT.17 Initial therapy consisting of NSPT and appropriate recare maintenance appointments are vital in preventing further periodontal destruction.9 Likewise, the reduction and suppression of P. gingivalis and the inflammatory markers from this pathogen are important in preventing and alleviating NAFLD symptoms.9 A pilot study investigated the association of P. gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actionmycetemcomitans and the severity of liver damage in NASH.5 Participants who visited their oral health professionals more regularly experienced less liver stiffness.

Saliva testing may be a helpful tool.20 Chairside oral microbiome testing for P. gingivalis has already been utilized to determine the progression of chronic periodontitis.21 Future application for mitigating systemic diseases could prove helpful in patients with NAFLD.

Saliva testing may be a helpful tool.20 Chairside oral microbiome testing for P. gingivalis has already been utilized to determine the progression of chronic periodontitis.21 Future application for mitigating systemic diseases could prove helpful in patients with NAFLD.

Dietary habits of the group with NAFLD contained higher amounts of carbohydrates and more than half reported drinking sugary, carbonated soft drinks.22 The combination of cariogenic dietary habits, high prevalence of xerostomia, poor dental hygiene, and less than optimal dental visit frequency placed these individuals at a high to extreme caries risk.23

The dental hygienist’s role in nutritional counseling and educating patients with NAFLD is integral to caries prevention and effective management of risk factors for liver disease.22,23 Recent studies have shown high-fructose corn syrup as a major dietary contributor to NAFLD development by activating the generation of fat through lipogenesis and blocking lipid breakdown.24 Individuals with NAFLD consume fructose-containing soft drinks two to three times more frequently than those with healthy livers.25 Fructose triggers increased gut permeability. These studies indicate the limit of energy through calorie restriction does not lessen the incidence of NAFLD if fructose is still present in the diet.24 Other factors contributing to NAFLD include diets high in fat and salt, especially when ingested with high-fructose corn syrup. Consequently, reducing exposure to high-fructose corn syrup may benefit patients with NAFLD considerably.24

A study looked at the relationship between NAFLD and ultra-processed food and found a dose-response relationship between the risk of NAFLD and the proportion and quantity of ultra-processed food consumption.26 Protective factors against fructose-induced NAFLD include omega-3 fatty acids in fish oils and Mediterranean diets.15,24 Vitamin C, epicatechin, and other flavanols found in natural fruit also protect against fructose-induced MetS.24

One consideration for treating patients with NAFLD is determining which anesthetic produces the least amount of adverse effects. Articaine is the local anesthetic of choice for individuals with chronic liver diseases, as only 10% to 15% of the anesthetic is metabolized in the liver.27 Alternatively, lidocaine, mepivacaine, and prilocaine are primarily metabolized in the liver, placing an unnecessary burden on the diseased organ.27

Another challenge for individuals with NAFLD is providing safe and effective analgesia. A recent literature review discussed how most analgesic medications can be used with chronic liver disease.28 However, lower doses and reduced frequency are recommended. The review concluded that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may place a risk of acute renal failure and should be avoided when possible. Opioids should be used sparingly.28

Conclusion

As the prevalence of NAFLD continues to increase, so should strategies to prevent and treat the disease. One way to address this is to recognize the probable bidirectional relationship between periodontitis and NAFLD. Dental hygienists play an important role in mitigating periodontal disease occurrence and progression. NSPT is essential to bring the oral cavity to a state of health as well as to diminish systemic chronic inflammation. Individualized patient education can go a long way in preventing oral and systemic diseases. Appropriate periodontal maintenance intervals may also help reduce the symptoms of NAFLD. Dental hygienists are geared to be essential healthcare team members for individuals with NAFLD through raising awareness, encouraging healthy lifestyle modifications, and improving overall oral health outcomes.

References

- Cheemerla S, Balakrishnan M. Global epidemiology of chronic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;17:365-370.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2018;67:328-357.

- Cleveland ER, Ning H, Vos MB, et al. Low awareness of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a population-based cohort sample: the CARDIA studyJ J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2772-2778.

- Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:11-20.

- Pischke S, Shiprov A, Peters U, et al. High prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with NASH- possible association of poor dental health with NASH severity. Ann Hepatol. 2023;28:100887.

- Åberg F, Helenius-Hietala J. Oral health and liver disease: Bidirectional associations — a narrative review. Dent J. 2022;10:16.

- Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2023;77:1335-1347.

- Hartleb M, Mastalerz-Migas A, Kowalski P, et al. Healthcare practitioners’ diagnostic and treatment practice patterns of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Poland: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:426-434.

- Kamata Y, Kessoku T, Shimizu T, et al. Periodontal treatment and usual care for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2022;13:e00520.

- Juanola O, Martínez-López S, Francés R, Gómez-Hurtado I. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Metabolic, genetic, epigenetic and environmental risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5227.

- Sookoian S, Pirola CJ, Valenti L, Davidson NO. Genetic pathways in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: insights from systems biology. Hepatology. 2020;72:330-346.

- Dongiovanni P, Valenti L. Genetics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65:1026-1037.

- Sookoian S, Pirola C. Genetics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathogenesis to therapeutics. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:124-140.

- Trépo E, Valenti L. Update on NAFLD genetics: From new variants to the clinic. J Hepatol. 2020;72:1196-1209.

- Romero-Gómez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatol. 2017;67:829-846.

- Kuraji R, Sekino S, Kapila Y, Numabe Y. Periodontal disease-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: An emerging concept of oral-liver axis. Periodontol 2000. 2021;87:204-240.

- Kuraji R, Shiba T, Dong TS, Numabe Y, Kapila YL. Periodontal treatment and microbiome-targeted therapy in management of periodontitis-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with oral and gut dysbiosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:967-996.

- Alakhali MS, Al-Maweri SA, Al-Shamiri HM, Al-Haddad K, Halboub E. The potential association between periodontitis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:2965-2974.

- Sato S, Kamata Y, Kessoku T, et al. A cross-sectional study assessing the relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and periodontal disease. Sci Rep. 2022;12:13621.

- Nibali L, Stephen A, Hagi-Pavli E, et al. Analysis of gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Dent. 2022;118:104065.

- O’Brien-Simpson NM, Burgess K, Lenzo JC, Brammar GC, Darby IB, Reynolds EC. Rapid chair-side test for detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Dent Res. 2017;96:618-625.

- Emelyanov DV. Results of questioning patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the conditions of dental practice. Wiadomosci Lek Wars Pol 1960. 2021;74(3 cz 1):504-507.

- 23.Featherstone JDB, Chaffee BW. The evidence for caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA®). Adv Dent Res. 2018;29:9-14.

- Jensen T, Abdelmalek MF, Sullivan S, et al. Fructose and sugar: A major mediator of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1063-1075.

- Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, et al. Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty Liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;48:993-9.

- Henney AE, Gillespie CS, Alam U, Hydes TJ, Cuthbertson DJ. Ultra-processed food intake is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2023;15:2266.

- Gazal G, Omar E, Elmalky W. Rules of selection for a safe local anesthetic in dentistry. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2023;18:1195-1196.

- Imani F, Motavaf M, Safari S, Alavian SM. The therapeutic use of analgesics in patients with liver cirrhosis: A literature review and evidence-based recommendations. Hepat Mon. 2014;14:e23539.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March/April 2025; 23(2):36-41.