The Gravity of Methamphetamine Addiction

Dental hygienists need to be aware of the signs of methamphetamine abuse and their effects on patients’ oral and general health.

The illicit use of methamphetamine has skyrocketed over the past several years. In 2004, 1.4 million people over the age of 12 used methamphetamine. In 2002, the percentage of users who were dependent on methamphetamine was 27.5%. In 2004, the percentage jumped to 59.3%.1

The growing use of this drug has obvious health implications, which have been widely publicized. It has particularly grave consequences on the dentition. In 2005, the American Dental Association issued a warning regarding methamphetamine’s effect on oral health.2 The policy statement stipulated that dental health care professionals should recognize the oral effects of methamphetamine abuse and modify treatment accordingly.

THE PROFILE

Methamphetamine, also known as “speed,” “crank,” or “ice,” is an extremely addictive synthetic amine that stimulates the release and blocks the re-uptake of neurotransmitters in the brain. These neurotransmitters, called monoamines (serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine), stimulate the reward center and control the flight/fight response. Long-term use can lead to depletion of the monoamines, which may account for the depression that heavy users typically experience. Methamphetamine can be smoked, snorted, orally ingested, or injected. Its effects are similar to cocaine but last much longer.3,4 While the effects of cocaine last from 20 minutes to an hour, the effects of methamphetamine can last up to 14 hours.

Production of methamphetamine is relatively easy and inexpensive. Formulas for creating methamphetamine in quantities small enough for personal use can be downloaded from the Internet.5 Ingredients used to make methamphetamine can be purchased from most major retail outlets. Corrosive substances used in its manufacture include lithium, muriatic and sulphuric acids, red phosphoru, and lye.6 Even when used properly, these substances can cause skin burns and, when used intraorally, can create sores and lead to infection. Other key ingredients include either ephedrine or pseudoephredrine, which can be obtained through over-the-counter cold and allergy medications. Due to the ease of manufacturing, people are producing the drug in makeshift laboratories in campers, motels, trunks of cars, and private homes. Access to pseudoephredrine has been curtailed by a series of restrictions placed on purchases as part of the United States Patriot Act.7 This has reduced some of the methamphetamine manufacturing in the United States but much of it has moved to organized drug cartels, based primarily in Mexico.4

Truck drivers, soccer moms, college students, and those in high stress jobs are among the many people who begin using methamphetamine because it increases wakefulness and physical activity while decreasing appetite. The gay community has also seen a rise in its use due to methamphetamine’s ability to boost libido and other lifestyle factors.8

PHYSICAL EFFECTS

Physiological changes associated with the use of methamphetamine may include insomnia, increased anxiety, paranoia, hallucinations, and aggressive tendencies.9 Drug-induced cardiomyopathy may occur in some users.10 These symptoms may include an irregular heartbeat, rapid heart rate, or increased blood pressure.9 An ischemic stroke caused by vasoconstriction may also occur.11 Initially the user may feel a sense of intense energy and euphoria12 along with a decrease in appetite. With increased use, the user may experience feelings of depression, auditory or visual hallucinations, and/or paranoia. A common form of paranoia experienced by meth users is the illusion that they are being threatened or are in danger. Cues that normally control behavior are inhibited, which may result in violent outbursts.4

Chronic users often have the sensation of bugs crawling under their skin, which is called formication clinically9 and informally called “meth mites,” “crank bugs,” and “snow bugs.” This sensation may cause methamphetamine users to obsessively pick and scratch at their skin causing skin lesions that can result in abscesses or cellulitis. Antibiotic treatment is frequently required to control the resultant infections.13 Skin lesions created from formication on the face or arms can often be identified during a routine extraoral exam (Figure 1).

Methamphetamine does increase the libido. This effect encourages users to engage in escalated risky sexual behavior, thus increasing the risk of contracting HIV, hepatitis C, and other sexually transmitted diseases. This risk is also increased through the sharing of contaminated needles.9

ORAL EFFECTS

The high incidence of oral disease in methamphetamine addicted patients is largely due to local environmental factors combined with the systemic effects of methamphetamine. Methamphetamine addicts exhibit a far greater incidence of dental caries than the average adult population and this condition is often referred to as “meth mouth.”14

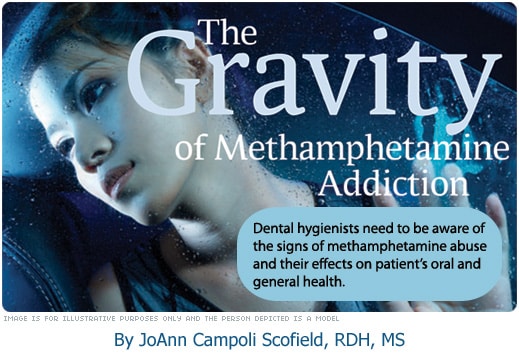

Methamphetamine decreases the salivary flow leading to persistent xerostomia. A high craving for sweets leads users to consume large amounts of carbonated beverages and fruit juices.15,16 When added to the effects of xerostomia, a distinctive pattern of rampant caries occurs. Clinically, it resembles early childhood or radiation caries appearing smooth and dark in color (Figure 2). While in a euphoric state, the user may constantly brux leading to temporomandibular joint syndrome, myofacial pain dysfunction, incisal wear/attrition, and massetter muscle hypertrophy. Crown fractures are common, leaving multiple retained roots throughout the mouth.14

Due to the effect of the drug on the brain, the body is fooled into thinking that nutritional requirements have been met leading to an inadequate diet. The oral manifestations experienced by this population are similar to those suffering from malnutrition or eating disorders. As with anorexia, a methamphetamine addict may exhibit signs of nutritional deficiencies including angular chelitis, candidiasis, or glossydynia.17

Periodontal diseases, which may be attributed to poor oral hygiene, are also significant among drug abusers. Patients may be poorly motivated due to the prolonged high created by the drug that can last for hours or days.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Regular visits to the dental office to maintain oral health are difficult due to the lifestyle of the addict. Missed appointments and nonpayment of services are common among active abusers. Also complications may arise, such as behavior management problems; dental neglect; and medical complications like elevated blood pressure and respiratory arrest. Pain tolerance may also decrease, resulting in failure of local analgesic agents.

TABLE 1. COMMON INDICATORS

- Rampant tooth decay

- Hyperthermia

- Severe xerostomia

- Paranoid behavior

- Poor oral hygiene

- Skin lesions

- Attrition

- Excessive perspiration

- Resting tachycardia

- Hypertension

- Weight loss

- Repetitive motor activity

- Dilated pupils

- Tremor

Medical history questionnaires should include questions about drug use. When drug abuse is suspected, nonjudgmental questions should be asked. For instance, a practitioner may ask if the patient has ever used drugs or alcohol more than they meant to in the past year.18,19 Blood pressure and heart rate should be measured before beginning any procedures.20 Evaluation for extraoral signs of drug abuse and a complete intraoral exam should be performed each time the patient is seen (Table 1). Patients may wear long sleeve shirts at inappropriate times to hide needle track marks.

Dentists and dental hygienists must be aware of drug pharmacology before dispensing drugs and anesthetics as adverse reactions can lead to serious complications. A medical clearance may be considered due to possible cardiovascular damage from long-term methamphetamine use. Postponement of planned treatment should be considered if any question of recent methamphetamine use exists. Dental health care providers with patients who are known users or suspected of using drugs, can ask them to sign a statement indicating they have not used any drugs within the previous 24 hours.

Good oral hygiene should be encouraged although compliance is an issue when dealing with an active user. Educational services and preventive treatment should be similar to those provided to any high caries risk patient who suffers from xerostomia. Fluoride treatments should be incorporated into the preventive appointment as well as a daily home fluoride regimen. A power toothbrush with a 2 minute timer (to encourage adequate brushing time) may be beneficial if patients are instructed on proper usage. In addition, patients should be taught about the damaging effects of the drug to general and oral health. Replacing fruit juice and high sugar carbonated drinks with water should be encouraged.

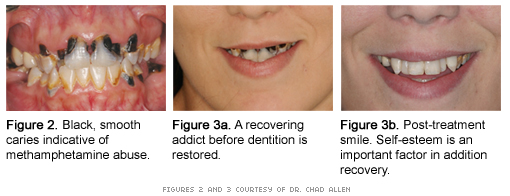

Self-esteem is an important aspect to address when treating recovering methamphetamine addicts. A nice smile without black, decaying teeth is important to their recovery so every effort should be made to stabilize the mouth and restore the dentition (Figures 3a and 3b).

Educating patients about the negative effects of the drug on oral and general health may be beneficial. This can be done through brochures left in the reception room or initiating conversation. Dentists and dental hygienists should be prepared to refer patients to an appropriate counseling service (Table 2).

TABLE 2. RESOURCES FOR REFERRAL

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Substance Abuse Treatment Facility Locator, www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov

- Cocaine Anonymous World Services, www.ca.org

- Narcotics Anonymous World Services, www.na.org

Identification of the drug abusing patient can be subtle or obvious. Usually, patients in recovery will share their drug use history so as not to jeopardize their recovery. Dental professionals need to be aware of the signs and symptoms in order to serve as a resource of support throughout dental treatment.

REFERENCES

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Methamphetamine use, abuse, and dependence: 2002, 2003, and 2004. Available at: www.oas.samhsa.gov/nhsda.htm. Accessed February 23, 2007.

- ADA Warns of Methamphetamine’s Effect on Oral Health. Available at: www.ada.org/public/media/releases/0508_release01.asp Accessed February 23, 2007.

- Freese TE, Miotto K, Reback CJ. The effects and consequences of selected club drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:151-156.

- Inaba D, Cohen WE. Uppers, Downers, All Arounders: Physical and Mental Effects of Psychoactive Drugs. 5th ed. Ashland, Ore: CNS Publications; 2004.

- Rawson RA, Anglin MD, Ling W. Will the methamphetamine problem go away? J Addict Dis. 2002;21:5-19.

- Stop Meth. How is methamphetamine made? Available at: www.stopmeth.com/made.htm. Accessed February 23, 2007.

- United States Congress House Committee on the Judiciary. Reauthorization of the USA Patriot Act (continued), Serial No 109-29, June 10, 2005, 109-110.

- Jefferson DJ, Shenfeld H, Murr A, et al. America’s most dangerous drug. Newsweek. 2005;146:40-48.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Research Report Series. Methamphetamine abuse and addiction. Available at: www.nida.nih.gov/PDF/RRMetham.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2007.

- Wijetunga M, Seto T, Lindsay J, Schatz I. Crystal methamphetamine-associated cardiomyopathy: tip of the iceberg? J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:981-986.

- Ohta K, Mori M, Yoritaka A, Okamoto K, Kishida S. Delayed ischemic stroke associated with methamphetamine use. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:165-167.

- Sommers I, Baskin D, Baskin-Sommers A. Methamphetamine use among young adults: Health and social consequences. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1469-1470.

- Lee NE, Taylor MM, Bancroft E, et al. Risk factors for community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1529-1534.

- Shaner JW. Caries associated with methamphetamine abuse. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2002;84:42-47.

- Saini T, Edwards PC, Kimmes NS, Carroll LR, Shaner JW, Dowd FJ. Etiology of xerostomia and dental caries among methamphetamine abusers. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2005;3:189-195.

- Shaner JW, Kimmes N, Saini T, Edwards P. “Meth mouth”: rampant caries in methamphetamine abusers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:146-150.

- Touger-Decker R. Oral manifestations of nutrient deficiencies. Mt Sinai J Med. 1998;65:355-361.

- American Dental Association. Drug Use. Available at: www.ada.org/prof/resources/topics/druguse.asp. Accessed February 23, 2007.

- Screening and Ongoing Assessment for Substance Use. New York: New York State Department of Health; 2005:11.

- Sandler NA. Patients who abuse drugs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:12-14.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2007;5(3): 16-18.