Strengthening Dentistry’s Quality Assurance

Documentation, patient communication, and risk management are integral to improving care and protecting oral health professionals.

This course was published in the March/April 2025 issue and expires April 2028. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 550

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the impact of quality assurance on patient safety, risk management, and overall care outcomes.

- Identify common documentation errors in dental records and strategies to ensure accurate, compliant, and legally sound recordkeeping.

- Describe effective provider-patient communication techniques to prevent miscommunication, mitigate patient aggression, and enhance workplace safety.

Published in 2000 as part of the United States National Academy of Medicine’s overarching Quality of Health Care in America Project, “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,”1 focused on the quality concerns and safety problems in the American healthcare system. Its goals include improving quality, fostering accountability, and identifying characteristics and factors enabling or encouraging continuous improvement in quality. This pivotal report proposed a set of recommendations to improve safety in healthcare.

Implementing clinical and administrative measures to identify, evaluate, and reduce the risk of injury to healthcare staff and visitors — as well as decrease the risk of loss to the organization as a whole — is key to effective healthcare risk management.1 An increase in aggressive behavior by patients also highlights an emergent need for further research, increased awareness, and education on risk-mitigating strategies within the dental community.

Quality Assurance System

The American Dental Association (ADA) began studying quality assurance (QA) in dentistry in July 1976 in collaboration with the Health Standards and Quality Bureau of the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. This work resulted in a two-volume report “Quality Assurance in Dentistry” and the executive summary was published in the Journal of the American Dental Association in 1979.2

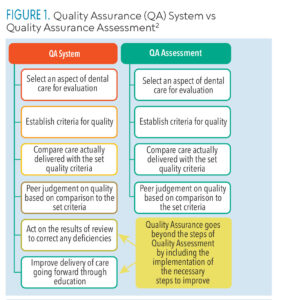

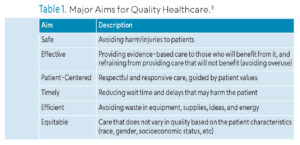

The executive summary distinguished the definitions/components of the QA system and QA assessment (Figure 1).2 It highlighted the difference of the QA process in dentistry — operating in hospitals, group practices, dental educational settings, and private dental offices — distinct dental care delivery settings requiring individualized QA systems. Regardless of the setting, however, and consistent with the six major aims for improving the quality of healthcare, dental care should be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (Table 1table).3

In 2008, the ADA established the Dental Quality Alliance (DQA), a 37-member organization including professional groups, such as the American Dental Hygienists’ Association, and dental education bodies, such as the American Dental Education Association; other stakeholders (providers, payers, public); and federal agencies.4 The DQA focuses on measures that identify and monitor strategies toward reducing incidence of oral disease and improving the effectiveness of care.

In 2008, the ADA established the Dental Quality Alliance (DQA), a 37-member organization including professional groups, such as the American Dental Hygienists’ Association, and dental education bodies, such as the American Dental Education Association; other stakeholders (providers, payers, public); and federal agencies.4 The DQA focuses on measures that identify and monitor strategies toward reducing incidence of oral disease and improving the effectiveness of care.

Administrative sources (quantitative information that includes encounters and claims), and qualitative data from patient records and surveys should be used in performance and quality evaluations.4 Quantitative measurements include those related to profit/loss and revenue reports, number of patients seen, number of procedures performed,and treatment and referral completion rates.5

Administrative sources (quantitative information that includes encounters and claims), and qualitative data from patient records and surveys should be used in performance and quality evaluations.4 Quantitative measurements include those related to profit/loss and revenue reports, number of patients seen, number of procedures performed,and treatment and referral completion rates.5

Qualitative measures, such as reviews of how well the standard of care is met, periodic chart review/audits, and patient surveys, have not been universally implemented.5 Meanwhile, clinical record-based measurement of patient health status is recognized as best predictive of quality, but lack of standardization in dental information systems and clinical records documentation complicates QA.4

The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) recommends6 that educational programs have a “formal written QA plan,” which may be broadened to dental practices outside of education. According to CODA, an ongoing review process centered on patient care and comprehensive standards should assess the appropriateness, necessity, and quality of the care provided. Furthermore, the cause of any treatment deficiencies will be identified in the QA process and lead to improved policies, procedures, and, ultimately, patient care outcomes.

Documentation

According to the ADA, patient records are critical to the successful provision of patient care.7 Carefully maintained patient records support both the legal and ethical responsibilities inherent to patient care.8

A dental record documents all interactions between the dental professional and the patient, serving as a record of the provider’s ethical responsibility in delivering care. To deliver patient care ethically, a dental professional must comply with proper recordkeeping. For example, providing care without informed consent violates the principle of patient autonomy.9 Not properly securing patient documentation is against the privacy rule and the principle of confidentiality within the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996.10 Omissions in dental documentation can also lead to misdiagnosed conditions, which would challenge principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence of care provided.11

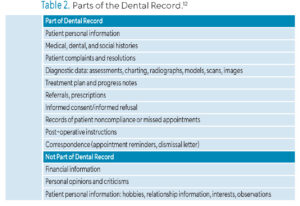

Thorough, precise, and accurate documentation of patient interactions is a dental professional’s strongest defense against malpractice claims.12 Even if a dental practitioner acted within the scope of care, diagnosed conditions properly, and provided adequate and appropriate treatment, it can not be proven without proper records.13 Any information from a dental record can be used in legal proceedings, supporting the legal responsibility for maintaining proper dental documentation. Dental records contain subjective and objective data. Table 2 describes what should and should not be included in dental records per ADA recommendations.13

Most complaints about dental documentation fall into three major categories:

Most complaints about dental documentation fall into three major categories:

- Inadequate documentation

- Incorrect documentation

- Falsified documentation14

In fact, inadequate or incomplete documentation can be a significant issue in cases of legal challenges. According to the ADA, common documentation errors include missing or incomplete details on dental findings, diagnoses, procedures, treatment plans, medical histories, and informed consent.13

Errors in documentation may lead to incorrect or inaccurate diagnosis, causing harm to the patient and opening a dental professional to disciplinary action and/or litigation. Additionally, tampering with documents, making deliberate changes, and falsifying any part of dental record are against the law.

To avoid errors in documentation, the ADA recommends reviewing dental records for accuracy, writing treatment notes as soon as possible, following a set format for clinical notes, such as SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, and plan) to avoid missing important details in charting or assessments, but making sure each chart entry is unique as is each patient and clinical case.

Each entry in the patient record must be signed by a designated provider. All necessary patient or legal guardian signatures must be on file as each part of the dental record is considered a legal document. Any correction to a clinical note must be followed by an addendum and signed by the authorized user. According to the ADA, it is the dentist’s responsibility to review all entries for accuracy and ensure compliance with insurance regulations.

In addition to being a legal and ethical responsibility of dental professionals, dental records are also regulated under HIPAA.10 HIPAA stipulates that patients may request access to their records at any time. Dental records may be shared with and reviewed by other healthcare professionals and insurance companies. Any omissions in dental records can negatively affect interprofessional communication, as well as serve as a basis for insurance fraud litigation.7 Moreover, as with all proper dental records, documenting patient-related communications, including occurrences of patient aggression toward clinicians or dental personnel, is equally salient as part of the quality control and risk management protocols in a dental setting.13

Effective Provider-Patient Communication

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 8% to 38% of healthcare workers worldwide will experience some form of physical violence during their careers, while an even larger proportion will encounter threatening verbal aggression, in most instances from patients.15 Healthcare workers most vulnerable to encountering aggressive or dangerous situations are those directly involved in patient care; this includes not only medical personnel but dental professionals as well.15

While few studies have investigated workplace violence or patient aggression toward dental professionals, one survey conducted by New York University College of Dentistry shed light on the prevalence of aggression experienced by dentists.16 Within a year, the study reported rates of 22.2% for physical assault, 55% for verbal assault, and 44.4% for reputational assault. Throughout their careers, these rates increased to 45.5%, 74%, and 68.7%, respectively. Moreover, practicing dental professionals are not the only ones experiencing patient aggression: other studies exploring dental students’ encounters with aggressive patients revealed they, too, have experienced a similar ratio of incidents.17,18

These findings suggest a higher occurrence of patient aggressive behavior against healthcare professionals than those reported by the WHO.16 Accordingly, the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Psychiatric Emergency Services recommends that staff undergo annual training in managing behavioral emergencies.19,20

Agitation represents a sudden behavioral crisis necessitating prompt intervention.19,20 Therefore, preemptive mitigation of safety risks begins with swift assessment and decision-making skills to thwart a hostile situation. When encountering an agitated patient, the engagement should be focused on four main objectives:

- Safeguarding the patient, staff, and others in the area

- Helping the patient manage his or her emotions and concerns to maintain or regain control of his or her behavior

- Avoiding the use of restraints whenever possible

- Steering clear of coercive interventions, which may escalate the agitation further19–21

Recognizing and accurately assessing patient agitation using a standardized scale by the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry is recommended. These guidelines suggest a practical, noncoercive approach to de-escalating a hostile patient encounter by respecting the patient’s personal space and avoiding a provocative or authoritative tone or demeanor. Clinicians should be aware of the following agitation assessment indicators in patients who are agitated or becoming agitated: motor hyperactivity, such as moving hands back and forth; pacing; tapping on surfaces; repeating statements; and raising of the voice.19–21

At the earliest indication of patient aggression, clinicians must first assess their surroundings for safety, be aware of accessible exit locations, remove any nearby objects that could be injurious, and maintain adequate personal space from the patient — a minimum of 2 feet. The manner in which healthcare providers communicate with patients is essential for preventing and de-escalating potentially aggressive encounters.

Verbal de-escalation and nonverbal communication skills are not only key to engaging the agitated patient, but can help him or her become an active partner in the process. The clinician should consider using techniques such as open-ended questions and reflective feedback to identify the patient’s wants and needs while maintaining concise and clear communication.19–21 Agreeing or agreeing to disagree also helps maintain a respectful dialogue, while setting clear limits and expectations facilitates better management of the interaction. Finally, offering the patient choices, maintaining optimism, and summarizing the exchange ensures mutual understanding and helps in calming the situation.19–21

Conclusion

Dental professionals’ knowledge and thorough application of the best practices in documentation and effective provider-patient communication, as key elements of the QA process, not only facilitate continuous advancement of quality of care, but also aid in preventing miscommunication and possible litigation, as well as aggressive or dangerous situations. Periodic training of all direct dental care providers and office staff will facilitate their awareness and readiness to address and prevent these negative outcomes.

References

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Stern SK, Morrissey SC, Mauldin J. Quality assurance in dentistry: executive summary, part 1J J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;98:81-85.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press ; 2001.

- Dental Quality Alliance. Quality Measurement in Dentistry A Guidebook. Available at ada.o/g/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/dqa/educational-resources/葠_䁷_guidebook.pdf?rev=ddef845838024bc7b72cf7312e8775b8&hash=CC40EC6E587CAC1778453826ADA15AB5. Accessed February 7, 2025.

- Boynes SG. Clinical quality assurance in the dental profession. Dental Economics. May 15, 2015.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Dental Hygiene Standards. Available at https://coda.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/coda/files/dental_hygiene_standards.pdf?rev=aa609ad18b504e9f9cc63f0b3715a5fd&hash=67CB76127017AD98CF8D62088168EA58. Accessed February 7, 2025.

- American Dental Association. Documentation Patient Records. Available at ada.org/resources/practice/practice-management/documentation-patient-records. Accessed February 7, 2025.

- Devadiga A. What’s the deal with dental records for practicing dentists? Importance in general and forensic dentistry. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2014;6:9-15.

- Benecke M, Kasper J, Heesen C, Schäffler N, Reissmann DR. Patient autonomy in dentistry: demonstrating the role for shared decision making. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20:318.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/health-insurance-portability-accountability-act-1996. Accessed February 7, 2025.

- Kumar V, Harish Y, Puranik M. Ethical and Legal Issues in Dental Practice. Int J Health Sci Res. 2017;3327:332-340.

- Gardiner MJ. Altered records. Available at https://insidedentistry.net/떉/葖/altered-records/. Accessed February 7, 2025.

- American Dental Association. Writing in the Dental Record. Available at ada.org/resources/practice/practice-management/writing-in-the-dental-record. Accessed February 7, 2025.

- Roerig M, Farmer J, Ghoneim A, et al. Developing a coding taxonomy to analyze dental regulatory complaints. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1083.

- World Health Organization. Preventing Violence Against Health Workers. Available at who.int/activities/preventing-violence-against-health-workers. Accessed February 7, 2025.

- Rhoades KA, Heyman RE, Eddy JM, et al. Patient aggression toward dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151:764-769.

- Rhoades KA, Heyman RE, Eddy JM, et al. Patient aggression toward dental students. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:586-592.

- Looper A, Esfandiari S. The prevalence of patient aggression toward dental students at a canadian university teaching clinic. J Can Dent Assoc. 2023;89:4.

- Roppolo LP, Morris DW, Khan F, et al. Improving the management of acutely agitated patients in the emergency department through implementation of Project BETA (Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1:898-907.

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:17-25.

- Stubbe DE. Psychiatric emergencies: empowering connections to de-escalate aggression. Focus J Life Long Learn Psychiatry. 2023;21:54-57.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March/April 2025; 23(2):32-35.