VGAJIC/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

VGAJIC/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Oral Health Implications of Menopause

Dental hygienists play an integral role in educating patients about the oral and systemic effects of menopause.

This course was published in the June 2019 issue and expires June 2022. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the four stages of menopause.

- Evaluate the effects of hormones on oral health.

- List oral manifestations associated with menopause.

- Develop a comprehensive care plan for the menopausal patient.

With nearly 3,000 women reaching menopausal age each day in the United States and living 25 years to 30 years beyond its onset, dental hygienists are poised to provide comprehensive care to women before, during, and after menopause.1 However, lack of knowledge about oral manifestations in menopause may hinder the ability to do so.2 Compiling comprehensive patient assessments facilitates the development of a care plan tailored to the patient’s needs and promotes collaborative care with health care providers. Management of menopausal oral manifestations includes routine oral hygiene, modifiable risk counseling, treatment specific to presenting conditions, and collaboration with the patient’s physician to provide medical care and rule out any underlying factors.

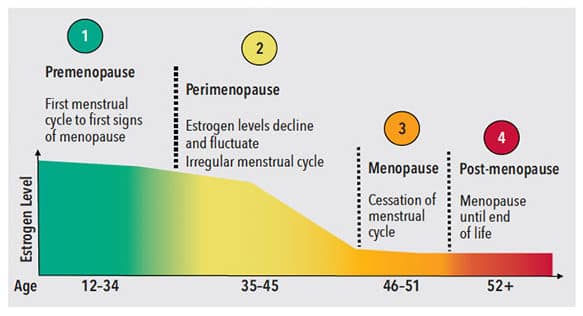

Menopause is composed of four stages: premenopause, perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause (Figure 1).3 Premenopause begins with first menses and ends with the first signs of menopause.3 Women begin the transition to perimenopause in their mid-thirties to early forties, which marks the decline of estrogen production by the ovaries.3 Perimenopause continues until the estrogen decline accelerates and menopause occurs.3 Menopause is defined as a natural event in a woman’s life, at an average age of 51, when ovulation and menstruation have ceased for 12 months.4 Menopause may also be induced by cancer therapy, nutritional deficiency, or total hysterectomy in which both ovaries are removed.4,5 Finally, post-menopause is defined as the years following menopause when systemic symptoms often ease up.3 Unfortunately, low estrogen levels put menopausal women at risk for several health conditions and oral manifestations.4,6

Two main sex hormones play a role in oral manifestation of menopause: estrogen and progesterone. Progesterone is involved in bone metabolism and is a bone formation-stimulating hormone.7 Estrogen decreases bone resorption and directly affects homeostasis by binding to receptors in oral tissues including mucosa, gingiva, and salivary glands.6,7 Decreased estrogen levels are linked to thinning, atrophic oral tissues; inflammation of gingiva; and reduced levels of clinical attachment.4,6,8 Evaluating the effects of hormones on oral tissues is the most important objective in creating a care plan for the menopausal patient.

Menopausal women report more oral discomfort, often in the absence of other oral changes, than premenopausal women.4,6 Research shows 60% of women with systemic symptoms of menopause simultaneously experience oral manifestations.9 Therefore, asking patients if they are experiencing hot flashes, vaginal dryness, or other symptoms attributable to menopause gives insight into the possibility of oral manifestations.

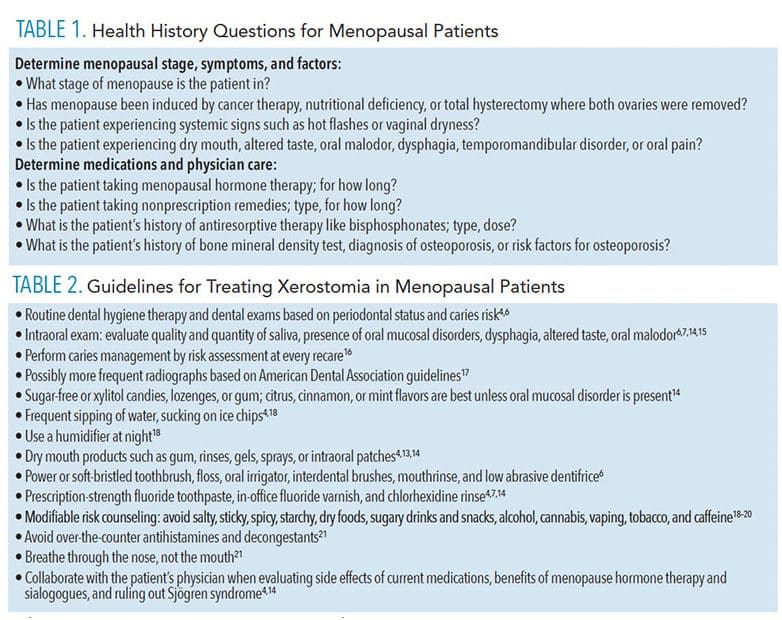

The oral-systemic effects of menopause are unique for each woman, making it difficult to predict the occurrence of oral signs and symptoms.6,7 Oral changes may include xerostomia, periodontitis, osteoporosis, oral mucosal disorders, and trigeminal neuralgia.4,6 Health history questions for menopausal patients should focus on determining the patient’s menopausal status, symptoms, and medication history (Table 1).

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), which supplements estrogen and progesterone during menopause, and healthy lifestyle changes may reduce the risk for systemic and oral conditions.6 The US Food and Drug Administration has approved MHT for treatment of moderate to severe systemic symptoms including, hot flashes, osteoporosis, and vaginal dryness.1 Studies indicate MHT increases saliva production, rebuilds mandibular bone mass, lessens oral discomfort, and reduces the severity of periodontal diseases by decreasing chemical messengers responsible for upregulating systemic inflammation.6,7 The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists cautions patients and providers to weigh risks and benefits and use the lowest dose of MHT for the shortest duration.1,5 Compliance with MHT may be an issue in some women who fear cancer, irregular bleeding, or other side effects.10 The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend the use of testosterone, progesterone alone, compounded bioidentical hormones, phytoestrogens, or herbal supplements.11

XEROSTOMIA

Xerostomia is the most common oral symptom reported in menopausal women affecting saliva production in parotid, submandibular, sublingual, and minor salivary glands.6,12 Dental caries, mucositis, infections, pain, altered taste, oral malodor, and dysphagia are higher in menopausal women experiencing oral dryness.6,13,14 Menopausal women experiencing xerostomia may also have difficulty removing dentures and experience allergies to metal or acrylic bases found in dentures or oral prosthesis.14 Patients may report dry mouth even though clinical examination fails to show any abnormality or cause.13 While this type of subjective xerostomia may be transient, objective xerostomia manifests as chronic dryness lasting more than 3 months.12,15 It is important to ascertain if the menopausal patient is also experiencing vaginal dryness, as the histology and response to sex hormones is similar to the oral mucosa.4,14 Table 2 provides guidelines for the treatment of xerostomia in menopausal patients.

PERIODONTITIS AND OSTEOPOROSIS

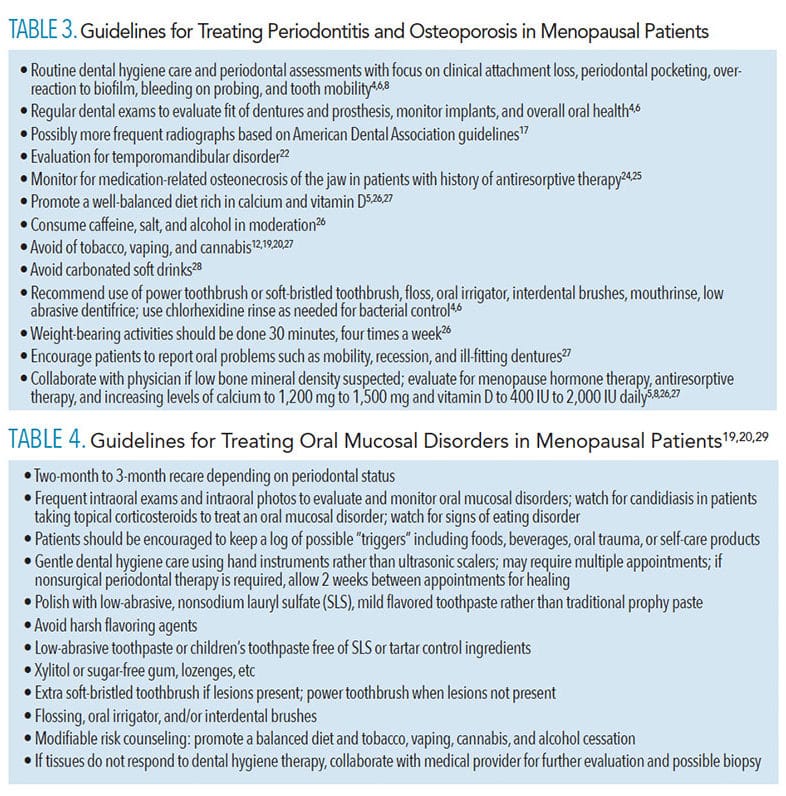

Tooth loss is three times more likely in women with osteoporosis.14 This is a concern because periodontitis and osteoporosis may not present symptoms until late in the disease process.4,6 The anti-inflammatory effect of estrogen on the periodontium and the role of progesterone in bone metabolism are compromised as hormones decline through the stages of menopause.8 Loss of bone mineral density due to increased osteoclast activity, decreased osteoblast activity, and production of inflammatory cytokines increase risk for osteoporosis.5,6 Additionally, inflammatory cytokines stimulated by biofilm increase gingival bleeding and stimulate osteoclasts.8 Nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) in post-menopausal women has been shown to be less effective when compared with premenopausal women.8

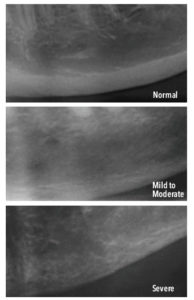

Decreased levels of estrogen may be associated with temporomandibular disorder (TMD).22 The combined effect of low estrogen and compression within the TM joint may lead to increased inflammation or osteoarthritis.22 The use of dental radiographs to screen for osteoporosis and periodontal diseases is supported.4 Although panoramic radiographs are not prescribed solely for the detection of osteoporosis, radiographic changes in the thickness of mandibular cortical bone may identify patients with systemic osteoporosis.4,7,23 In particular, mandibular inferior cortical bone width of less than 3 mm, in the location inferior to the mental foramen, may be indicative of osteoporosis (Figure 2).23 Assessment information garnered from extraoral exam and radiographs may be used to collaborate with the patient’s physician concerning her overall bone health. Osteoporosis screening is encouraged for menopausal women, especially if they are petite, thin, Caucasian, Asian, or have a family history.22

Treatment for oral osteoporosis may include antiresorptive medications.5,24 Dental hygienists must also be aware that patients with a history of denosumab and bisphosphonate medications are at a greater risk for exposed, poor healing bone known as medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ).24,25 A thorough medical and dental history is justified to identify patients at risk for osteonecrosis. Medications such as steroids, blood thinners, thyroid medications, and some anticonvulsants increase the rate of bone loss if not used as directed.26 Clinical recommendations should be based on the duration and type of antiresorptive therapy administered.26 Potential risk factors for MRONJ include high doses of antiresorptive medications taken for more than 2 years for cancer, corticosteroid use, diabetes, periodontitis, tobacco use, and wearing dentures.24,25 Discontinuing antiresorptive therapy does not eliminate the risk for MRONJ.25 Presently, there is no effective treatment for MRONJ, so prevention—including biofilm control; limiting alcohol consumption; and cessation of smoking, vaping, and cannabis—is important.24,25,30 Current treatment recommendations include antiseptic rinsing, systemic antibiotics, removal of necrotic bone, controlling pain, and preventing infection.25 Although minimal dento-alveolar manipulation is preferred, NSPT is not contraindicated.24,30 Research suggests bisphosphonate therapy actually improves NSPT outcomes and may act as an adjunct treatment for periodontal diseases and preservation of alveolar bone mass.4,31 The American Dental Association suggests the benefits of treating active dental and periodontal disease outweigh the risk of developing MRONJ.24 Patients with a history of antiresorptive therapy must give consent for treatment after being informed of the risks and benefits of dental care.25 Table 3 provides guidelines for treating periodontitis and osteoporosis in menopausal patients.

ORAL MUCOSAL DISORDERS

Due to decreased estrogen levels during menopause, the oral mucosa thins, becoming more prone to inflammation and loss of clinical attachment.4,6 Menopausal women may develop oral mucosal disorders such as burning mouth syndrome (BMS), gingivostomatitis, candidiasis/angular cheilitis, lichen planus, benign pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, Sjögren syndrome, and oral ulcerations following mechanical trauma.4,6,14 These disorders reduce the effectiveness of the oral mucosa as a barrier, thereby increasing the likelihood of disease.8

Directly related to reduced estrogen production, BMS typically occurs 3 years before menopause and 12 years after menopause.6 Normally, oral burning sensations are related to local and systemic factors such as candidiasis, lichen planus, xerostomia, diabetes, side effects of medication, and parafunctional habits.14,32 However, true BMS only applies if burning sensations occur in clinically healthy oral mucosa in the absence local and systemic factors.32 Patients often report bilateral, painful, burning sensation in the lips, tongue, palate, gingiva, and areas of denture support.4,15 Altered taste may be concomitant with BMS.6,32 Typically, symptoms of BMS worsen over the course of the day affecting nutrition, causing extreme thirst, and possibly interfering with sleep.6,32 Patients may experience irritability, anxiety, and depression with BMS due to the pain.32 Because diagnosis is based on exclusion of other conditions, clinical evaluation of patients presenting with correlating symptoms and collaborative medical care are important.6,32 When gathering information about BMS history, question the patient about duration, intensity, location, and aggravating and relieving factors of pain.32 An organized approach between dental professionals and medical providers is necessary to consider various etiologies.32 Treatment may include MHT, low-dose topical or systemic clonazepam, psychological counseling, or tricyclic antidepressants.4,14,15

Menopausal gingivostomatitis is characterized by atrophic gingiva that readily bleeds and appears abnormally pale and dry or shiny and erythematous.4 This condition, often resulting from hyposalivation, does not affect underlying connective tissue and bone.4,33 An erosive form of gingivostomatis presents with erythema, erosion, vesicles, and sloughing gingiva involving the full width of the gingiva, typically on the buccal aspect.4,33 Due to the fragile nature of the gingiva, patients frequently experience discomfort. Treatment may include topical steroids and vitamins, in addition to general guidelines for oral mucosal disorders.33 Table 4 lists guidelines for treating oral mucosal disorders in menopausal patients.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists play an integral role in counseling patients about the oral and systemic effects of menopause, based on their current stage, and collaborating with the dentist and medical providers to ensure patients receive optimal care and treatment.

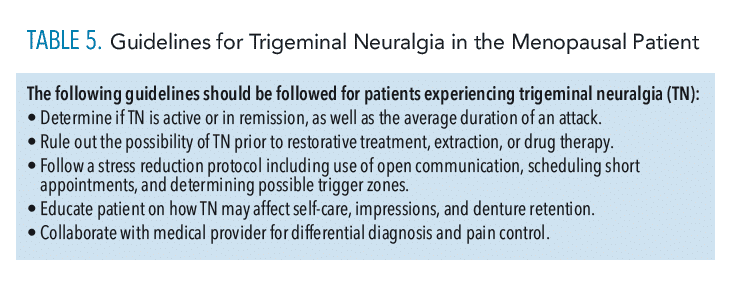

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is thought to be caused by deterioration of the protective sheath around the trigeminal nerve or by compression of the superior cerebellar artery on branches of the trigeminal nerve.5,34 This disorder, frequently experienced with menopause, is characterized by a pins and needles sensation that escalates to severe, unilateral pain in the face along the trigeminal nerve.34 These attacks can last for days or weeks, followed by remission of months or years.34 Unfortunately, the frequency increases over time and may become disabling.34 Often confused for a toothache, thorough dental and oral examination is necessary prior to restorative treatment, extraction, or drug therapy to rule out TN.34 The patient may fear dental procedures including DHT, will aggravate their facial pain, making open communication and stress reduction protocol essential.5 Part of this communication is asking the patient if they have any known triggers zones in the face which may cause an attack if touched.34 Dental hygienists are in a position to determine if TN is active or in remission and schedule short appointments to accommodate patient needs. It is important to realize this painful disorder may affect oral hygiene, impressions, and denture retention.5,8 Referral to a physician is often needed for further treatment and to rule out the possibility of a tumor or multiple sclerosis.34 Anticonvulsants and muscle relaxants are commonly used to treat symptoms of TN.5, 34 See Table 5 for guidelines for trigeminal neuralgia in the menopausal patient.

REFERENCES

- Goodman N, Cobin RH, Ginzburg SB, Katz IA, Woode DR. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause. Endocr Prac. 2011;17:949–954.

- Rothmund WL, O’Kelley-Wetmore AD, Jones ML, Smith MB. Oral manifestations of menopause: An interprofessional intervention for dental hygiene and physician assistant students. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91:21–32.

- Cleveland Clinic. Menopause, Perimenopause, and Postmenopause. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15224-menopause-perimenopause-and-postmenopause. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Mutneja P, Dhawan P, Raina A, Sharma G. Menopause and the oral cavity. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:548–551.

- Peacock K, Ketvertis KM. Menopause. Tampa, Florida: StatPearls Publishing LLC: 2018.

- Grover CM, More VP, Singh N, Grover S. Crosstalk between hormones and oral health in the mid-life of women: a comprehensive review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2014;4(Suppl):S5–S10.

- Hariri R, Alzoubi EE. Oral manifestations of menopause. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2017;7:00247.

- Sumadhura C, Prasanna J, Sindhura C, Karunakar P. Evaluation of periodontal response to nonsurgical therapy in pre- and post-menopausal women with periodontitis. Indian J Dent Res. 2018;29:298–302.

- Ben Aryeh H, Gottilieb I, Ish-Shalom S, David A, Szargel H, Laufer D. Oral complaints related to menopause. Maturitas. 1996;24:185–189.

- Apoorva SM, Suchetha A. Effect of sex hormones on the periodontium. Ind J Dent Sci. 2010:2:36–40.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202–216.

- Tuppini AR, Wilson N. Dry mouth: Advice and management. Available at: pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/learning-article/dry-mouth-advice-and-management/20204481.article?firstPass=false. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Rukmini JN, Sachan R, Nilima S, Meghana A, Malar CI. Effects of menopause on saliva and dental health. J Int Soc Pre Community Dent. 2018;8:529–533.

- Shigli K, Giri PA. Oral manifestations of menopause. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci. 2015;4:4–8.

- Dutt P, Chaudhary SR, Kumar P. Oral health and menopause: A comprehensive review of current knowledge and associated dental management. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:320–323.

- Featherstone JDB, Chaffee BW. The evidence for caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA®). Adv Dent Res. 2018;29:9–14.

- American Dental Association. Dental radiographic examinations: recommendations for patient selection and limiting radiation exposure. 2012. Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/Dental_Radiographic_Examinations_2012.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Dry Mouth. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/health-info/dry-mouth/more-info. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- American Dental Association. Cannabis: Oral Health Effects. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/cannabis. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Froum S. Vaping and oral health: It’s worse than you think. 2019. Available at: perioimplantadvisory.com/articles/2019/01/vaping-and-oral-health-it-s-worse-than-you-think.html. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Mayo Clinic. Dry Mouth Treatment: Tips for Controlling Dry Mouth. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dry-mouth/expert-answers/dry-mouth/faq-20058424. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Cleveland Clinic. Hormones and Oral Health. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/11192-hormones-and-oral-health. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Gulashi A. Osteoporosis and jawbones in women. J Int Soc Prev Comminity Dent. 2015;5:263–267.

- Hellstein JW, Adler RA, Edwards B, et al. Managing the care of patients receiving antiresortive therapy for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:1243–1251.

- American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Available at: aaoms.org/docs/govt_affairs/advocacy_white_papers/mronj_position_paper.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Cleveland Clinic. Menopause and Osteoporosis. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/10091-menopause–osteoporosis. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- National Institutes of Health Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center. Oral Health and Bone Disease. Available at: bones.nih.gov/health-info/bone/bone-health/oral-health/oral-health-and-bone-disease. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- United States National Library of Medicine. Soft drinks and osteoporosis with WHI participants. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03371433. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Burkhart N, Rees T. Guidelines—mucosal disorder appointments. Available at: https://dentistry.tamhsc.edu/olp/about/mucosal-disorders.html. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- Fede OD, Panzarella V, Mauceri R, et al. The dental management of patients at risk for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: New paradigm of primary prevention. Biomed Res Int. 2018 Sep 16;2018:2684924.

- Akram Z, Abduljabbar T, Kellesarian SV, Hassan MIA, Javed F, Vohra F. Efficacy of bisphosphonate as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal therapy in the management of periodontal disease: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:444–454.

- Dahiya P, Kamal R, Kumar M, Gupta NR, Chaudhary K. Burning mouth syndrome and menopause. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:15–20.

- Hasan S. Desquamative gingivitis clinical signs in mucous membrane pemphigoid: Report of a case and review of literature. J Pharm Bioall Sci. 2014;6:122–126.

- Mayfield Brain and Spine Clinic. Trigeminal Neuralgia (Facial Pain). Available at: https://mayfieldclinic.com/pe-trin.htm. Accessed May 23, 2019.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2019;17(6):40–43.

Great and interesting course!