Oral Health and Stroke

Dental hygienists play an important role in the promotion and maintenance of oral health in patients recovering from stroke.

This course was published in the July 20012 issue and expires 7/31/15. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define the different types of strokes.

- Identify risk factors for stroke.

- Explain the problems faced by patients with stroke in maintaining their oral health.

- Detail strategies for improving the oral care of this patient population and individuals at risk.

Ischemic stroke includes three subtypes: thrombotic, embolic, and transient ischemic attack (TIA). Thrombotic stroke occurs when a clot forms in an artery that is already narrow. Embolic stroke (cerebral embolism) happens when an artery is blocked by a blood clot (arterial embolus) that originates from some other area of the body. TIA, often called a mini stroke, results when blood flow stops to a part of the brain for a short time. A TIA is different from a stroke because the blockage breaks up quickly and dissolves without infarction (tissue death). TIA is considered a warning sign of future stroke if preventive measures are not taken.2 Hemorrhagic stroke (20% of occurrences) results from blood vessels in the brain bursting open (also referred to as an aneurysm). Some people have weakened vessel walls that make hemorrhagic stroke more likely.1,2

Hemorrhages cause damage to brain tissue in one of two ways:

- An intracerebral (inside brain) hemorrhage is caused by the sudden rupture of an artery within the brain. Blood is then released, compressing brain structures.2

- A subarachnoid (surrounding tissue) hemorrhage is also caused by sudden rupture of an artery, but the location of the burst leads to blood filling the space surrounding the brain rather than inside it.2

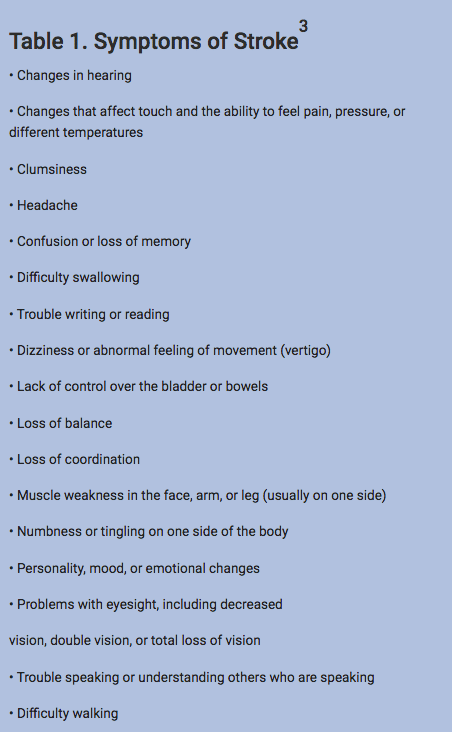

Symptoms of stroke (Table 1) often start suddenly.3 They may occur while the person is lying flat and worsen with a change in position. Outcomes for stroke patients can be improved if the incident is caught early and immediately addressed.

![]() HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

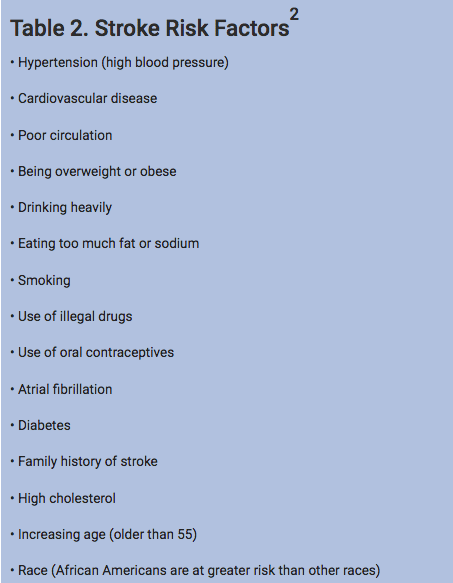

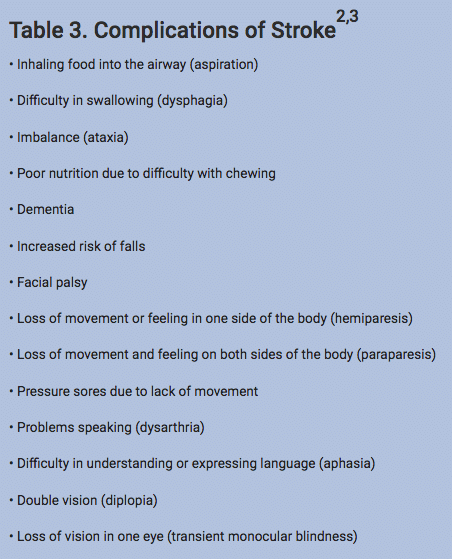

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is a major cause of stroke because of its relationship to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis or hardening of the arteries occurs when plaques build up in the arteries causing them to narrow. The added pressure on artery walls caused by high blood pressure weakens them, making them more susceptible to plaque, eventually causing a stroke.2 Uncontrolled high blood pressure increases the risk of stroke by four times to six times.3 Table 2 includes additional risk factors. Stroke can cause a variety of health complications—ranging from aspiration to ataxia. Table 3 provides a more complete list.2,3

THE ORAL CAVITY

Stroke negatively impacts oral health. It affects facial muscles and the ability to chew and swallow, which can lead to malnutrition and increased risk of caries and periodontal diseases. Stroke patients are at risk of aspiration pneumonia, which is caused by inhaling food debris and bacterial biofilm into the airway. Aspiration results when the swallowing reflex is damaged. The first stage of swallowing starts when food is introduced into the mouth and the lips seal. Sealing the lips is a crucial step to the facial muscles working successfully together in the mastication process. During the second stage, the tongue sweeps the food into the buccal and labial vestibules, where broken-down food or bolus is collected. Food debris is left in the buccal and labial vestibules when there is damage from stroke.3 The bolus is collected at the back of the mouth, where it is rapidly propelled into the pharynx. In the third stage, breathing stops when food enters the pharynx, the soft palate rises to seal the nasopharynx, the glottis (opening of the larynx) closes, and the larynx is pulled up while the epiglottis tilts back to cover it.3 If the nasopharynx is unable to seal, food and debris will enter the nasal area and create the potential for infection and aspiration.

![]() ORAL HYGIENE AFTER STROKE

ORAL HYGIENE AFTER STROKE

Good oral hygiene is difficult to maintain in stroke patients because they may not have the necessary dexterity and caregivers may not be trained in oral hygiene techniques.4 Dietary adjustments to manage food consistency include thickening fluids and dietary food supplements, which increase plaque formation.4 Adequate nutritional intake is extremely important for recovery and to avoid malnutrition. Food supplements and recommendations to consume food throughout the day to maintain sufficient calories can increase the risk of dental caries, especially if medications are causing xerostomia. 3 Facial palsy and loss of sensation can cause pooling of food debris on the side affected by the stroke, allowing for bacterial accumulation. Impaired swallowing and facial paralysis can increase the amount of time when teeth and oral tissues are exposed to cariogenic food debris, increasing the risk of tooth decay.3,4

Special oral hygiene instructions for stroke survivors and their caregivers are essential to maintaining good oral health.2,3 There are many oral hygiene devices made especially for special needs patients. Three headed toothbrushes clean more of the tooth surface with each movement of the brush (Figure 1). Power toothbrushes are efficient at plaque biofilm removal and offer a large handle for patients who have lost some dexterity. Manual toothbrushes, interdental cleaners, and specialized end-tufted and soft pediatric brushes can be modified by adding larger handle grips with tennis balls or grips made for craftsman tools(Figure 2).4 Toothbrushes with special suction devices are available for patients who have swallowing problems. Caregivers can assist stroke survivors with flossing and brushing by standing behind them, pulling their lower lip down, and cupping their chin while moving the toothbrush across their teeth in a circular motion.

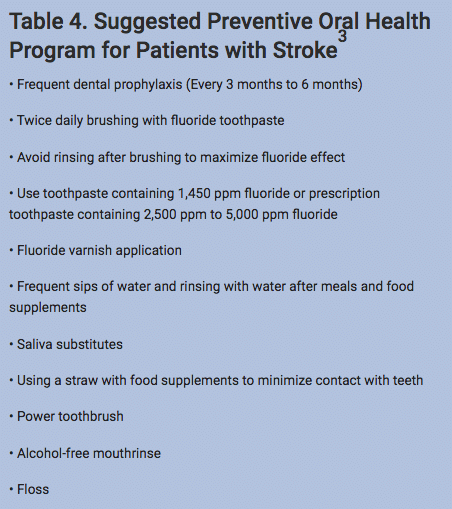

The “hand-over-hand” technique is another way of assisting with oral hygiene if patients want to participate in their own oral hygiene. Prescription fluoride toothpaste can be used but stroke patients must expectorate to minimize aspiration. Patients should avoid rinsing after brushing with prescription fluoride dentifrice to maximize fluoride’s effects. Table 4 provides additional components of an effective preventive program.

![]() HEALTH OF ORAL TISSUES

HEALTH OF ORAL TISSUES

Xerostomia is very common among stroke survivors due to their medication use. Xerostomia can cause dysgeusia, difficulty in chewing and swallowing, and improper denture fit.3,5 Poor clearance of food from the mouth in the presence of xerostomia reduces the protective influence of saliva.6,7 Reduced saliva can be addressed with daily oral hygiene, hydration (at least eight 8-oz glasses of water per day), sugarless mints and gum, use of a humidifier, alcohol-free mouthrinses (alcohol is drying to tissues), and saliva substitutes containing carboxy – methycellulose (used in foods to thicken and coat). Caries is more prevalent among those with dry mouth, thus preventive measures should be implemented, such as fluoride therapy. Dehydration contributes to dry mouth and should be monitored in stroke survivors.7

Intubated stroke patients suffer from severe xerostomia because their mouth is open all the time and the breathing machine is extremely drying to the oral tissues. Lack of oral care during intubation can lead to dry tissues, sore throat, reduced wound healing, and oral ulcerations.3 The tube should be frequently repositioned to prevent lip soreness but steps must be taken to ensure the tube remains secure. Oral care must start immediately after intubation to maintain health of the oral tissues.3,6

Dry and cracked lips should be carefully cleaned with water and lubricated with a nonpetroleum jelly product. Alcohol-free oral products should be chosen to prevent further drying of the oral tissues.6 Lemonglycerin swab sticks cause irritation and erosion because of their acidity and should be avoided. Plain swab sticks dipped in water or saliva substitutes will keep the tissues hydrated.8

MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

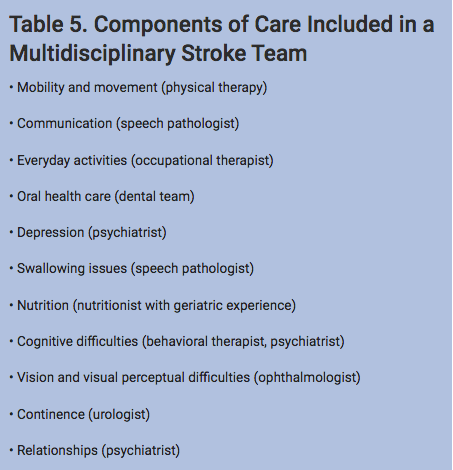

Treatment and rehabilitation of the stroke patient must begin with a multidisciplinary team approach.3,8 Table 5 lists the components of care included in a multidisciplinary stroke team. The oral health care provider plays a two–fold role in stroke prevention and rehabilitation. First, oral health care providers can recognize stroke risk factors and refer patients to a physician or specialist. Second, they can provide essential oral health care to patients recovering from stroke.3,4

Collaboration among the team can identify an appropriate oral care plan for stroke survivors. The dental team must become the liaison between the health, social, and voluntary agencies to identify dental care programs within the community. People recovering from stroke face barriers to accessing oral health care services, including transportation and mobility issues, problems with communication, cognitive impairment, fear and anxiety, inability to cooperate, dependence on others, negative attitudes toward oral care, and inadequate knowledge of health care.4

Some residential facilities for stroke survivors are not equipped to provide oral health care but are required by law to offer a reasonable alternative.3 Oral health services are in great need for stroke patients in long-term care facilities. Thorough oral assessment; policy on care and safe-keeping of a resident’s dentures; dental input to multi/interdisciplinary assessments; training for health care professionals by dental hygienists; oral health advice and support for resident, family, and caregivers; onsite dental clinics with assessment and treatment services; and procedures and standards for dental programs in facilities with monitoring and auditing standards are all part of an effective standard of care.3 Health care professionals need training in oral health to promote prevention and rehabilitation to improve both the oral and systemic health of people who have experienced a stroke.

Dental hygienists are important players in the continuum of care needed to support the oral health needs of people recovering from stroke. From stroke prevention to providing adaptive strategies to stroke survivors with dexterity limitations, dental hygienists can make a significant difference in the promotion and maintenance of oral health among this patient population.

References

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Stroke. Available at: www.cdc.gov/stroke. Accessed June 22, 2012.

- Schrijvers EM, Schürmann B, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of vascular dementia. Stroke. 2012;43:315–319.

- British Society of Gerodontology. Guidelines for the Oral Healthcare of Stroke Survivors. Available at: www.gerodontology.com/forms/stroke_guidelines.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2012.

- Talbot A, Brady M, Furlanetto DL, Frenkel H, Williams BO. Oral care and stroke units. Gerodontology. 2005;22:77–83.

- Pow EH, Leung KC, Wong MC, Li LS, McMillan AS. A longitudinal study of the oral health condition of elderly stroke survivors on hospital discharge into the community. Int Dent J. 2005;55:319–324.

- Fiske J, Griffiths J, Jamieson R, Manger D. Guidelines for oral health care for long-stay patients and residents. Gerodontology. 2000;17:55–64.

- Staff-led interventions for improving oral hygiene in patients following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;18:CD003864.

- Sheiham A, Steele JG, Marcenes W, et al. The relationship among dental status, nutritional intake, and nutritional status in older people. J Dent Res. 2001;80:408–413.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2012; 10(7): 50-52, 55.

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE ORAL HYGIENE AFTER STROKE

ORAL HYGIENE AFTER STROKE HEALTH OF ORAL TISSUES

HEALTH OF ORAL TISSUES

[…] stroke. Oral health professionals can arm caregivers and patients who have experienced stroke with special self-care instructions, helpful oral hygiene devices, and dietary adjustments to support effective oral […]