Optimizing Ultrasonic Instrumentation

Magnetostrictive ultrasonic insert selection and correct technique in periodontal therapy.

In periodontal therapy, ultrasonic insert selection and correct technique are paramount to efficacious ultrasonic instrumentation. Ultrasonic insert selection is based on the extent and type of deposits, mode of attachment of the deposit, and periodontal conditions such as gingival inflammation, pocket depth, and pocket shape. Therefore, clinicians need to use a combination of traditional inserts and precision thin (micro-ultrasonic) inserts to achieve optimal clinical outcomes.

In periodontal therapy, ultrasonic insert selection and correct technique are paramount to efficacious ultrasonic instrumentation. Ultrasonic insert selection is based on the extent and type of deposits, mode of attachment of the deposit, and periodontal conditions such as gingival inflammation, pocket depth, and pocket shape. Therefore, clinicians need to use a combination of traditional inserts and precision thin (micro-ultrasonic) inserts to achieve optimal clinical outcomes.

Traditional tips are used in initial therapy for moderate to heavy deposits because they are wider in diameter, allowing them to be used at moderate power. The mode of deposit attachment is also considered. When deposits are tenacious, hand-activated instruments, such as periodontal files (Hirschfeld 3/7 and 5/11), should be used to reduce the chance of burnishing deposits with a traditional ultrasonic tip.1,2 Clinical evidence shows that ultrasonic instrumentation can burnish calculus, which negatively affects healing and clinical outcomes.1 After deposits are reduced in size, precision thin ultrasonic inserts can be employed.

INSERT DESIGN AND SELECTION

Precision thin inserts or tips come in a set of three and are available for all ultrasonic units. Different companies manufacture different shapes, diameters, and curvatures. The surfaces of the working end of a magnetostrictive insert and the order of energy generated are important elements of effective ultrasonic instrumentation (Figure 1). The tip of a magnetostrictive insert is functional on all sides and the tip moves in an elliptical motion. The point generates the greatest amount of energy and is never adapted to the tooth surface due to potential discomfort for the patient and damage to the root.3 The concave surface of the insert tip generates the second greatest amount of energy and, again, is not adapted to the tooth due to the difficulty of correct adaptation. The convex surface or back generates less energy than the concave portion and the point. The lateral surface generates the least energy. For piezoelectric units, the tip moves in a linear fashion, thus, the lateral edges or sides of the tip generate the most energy.

The use of all three precision thin inserts in a set is recommended to ensure all areas of the tooth are reached. The straight, as well as the curved right and left tip designs, are critical to employ for effective results with maintenance therapy, especially if deep and/or narrow pockets exist. The right and left tips are designed like the Nabers probe or universal curets and are indicated to debride proximal tooth surfaces of molars and premolars. They are ideal to reach deposits under contacts and they adapt to furcations well. The straight tip is used in the anterior regions and in deep narrow pockets. A thorough and effective debridement in maintenance therapy involves application of all three insert designs in various areas of the dentition.

ADAPTION AND ACTIVATION

There are two schools of thought about the adaptation of precision thin inserts in clinical practice. One recommendation is to apply the tip of the insert on buccal and lingual surfaces like a universal curet by selecting the tip that wraps around the mesial surface. This technique must be used with caution to assure that the point is not directed inward toward the root. Improper use of the point will damage the root surface over time.4 It is a technique that should only be used with the lowest power setting and the lightest touch by a skilled clinician who is well-versed in root morphology. The second school of thought is to apply the tip of an insert in the opposite fashion by using more of the back of the insert. This technique prevents the possibility of over rolling the insert and using the point, however, it requires adjustment of the handpiece position for mesial surfaces to avoid directing the point toward the soft tissue. The most important factor is that the last 2 mm to 3 mm of the instrument (ie, the tip) must be in contact with the tooth at all times2 and be adapted so that the point is not directed in toward the root and the soft tissue is not impinged.

The use of periodontal charting is critical for effective instrumentation. It should be referenced for pocket topography, furcations, and depth of insertion of tips. After the ultrasonic unit is tuned or set on low power for biofilm removal during maintenance therapy, a gentle modified pen grasp is used during instrumentation. The handpiece should be balanced to eliminate any torque on the handpiece by the cord. The cord can be draped over the forearm or secured between the fingers in a neutral loop to reduce the cord “drag,” which is important in protecting the musculoskeletal health of the clinician.

The tip is activated using an extended grasp and a soft tissue or alternative fulcrum with the lightest possible pressure. Adapt the straight tip as close to 0° as possible (parallel) or at no more than a 15° angle to the surface of the tooth. Right and left inserts are also adapted so they are parallel to the tooth to avoid the use of the point of the tip and to adapt the lateral surface, which generates the least amount of ultrasonic energy. Increasing the tooth-to-tip angle greater than 15° can cause root damage, tissue distention, patient discomfort, and less effective deposit removal.

>The tip is inserted subgingivally with the lateral surface or convex back of the tip (magnetostrictive) or the lateral edge or side (piezoelectric) against the tooth to insure maximum efficacy and avoid tissue trauma. The lateral surface or back of the tip is applied at the distal line angle and moved toward the contact to negotiate the distal surface. Then the tip is reinserted at the distal line angle and moved across the buccal (or lingual) to the mesial line angle and midline of the mesial proximal surface. Clinicians might choose to instrument all distals first and then rotate the insert in the handpiece (magnetostrictive) with the nondominant hand to debride buccal/lingual and mesial surfaces, unless a swivel design is used.

Use multiple horizontal, oblique, and/or vertical overlapping strokes to move the tip over every square millimeter of the tooth surface. Keep the insert moving at all times for effective debridement and patient comfort. This overlapping stroke is always light and brush-like. The overlapping strokes must be very close together in periodontal maintenance therapy to effectively debride the biofilm and light deposit. Too much pressure on the insert can reduce effectiveness and cause discomfort for the patient. With proper technique most patients should not feel the tip.

Full coverage of the pocket is recommended with controlled short overlapping strokes. The overlapping strokes can be a little faster than with hand activated instrumentation because the purpose of debridement in periodontal maintenance therapy is to remove biofilm and lighter, newly formed deposits.3 If a more tenacious deposit is encountered, the clinician can use a more productive surface of the tip, decrease the hand speed of movement,4 or approach the deposit from a different angle with the tip. As a last resort, increase the power slightly or change to a different tip. In some cases, clinical outcomes have shown that precision thin inserts on low power do not always remove calculus completely.1 An explorer is still the instrument of choice to evaluate the final clinical endpoint of calculus removal or tactile feeling of lack of deposit, especially in the absence of endoscopic evaluation.

TREATING FURCATIONS

Prior to depressing the rheostat, place the inactivated tip subgingivally to feel for the furcation entrance, using the terminal end of the tip to explore the area. Adapt the tip to access the depth of the pocket. To reduce tissue distention, keep the tip closed or against the root surface at all times. Either side of the same tip may be used to access the walls of the furcation as well as the roof of the furcation. Selection of the right or left tip for debridement of furcations is variable depending on the height of the gingiva and access. Mentally visualizing the specific topography is important to effective debridement. The thin tip of precision thin inserts can promote effective instrumentation when compared to a curet that is wider. The same may be true for a narrow precision thin insert in a deep pocket.

The clinician should consider using endoscopic evaluation and assessment for inner depressions of furcations as well as instrumentation of the roof of the furcation. These areas are very difficult to debride effectively and, if an endoscope is an option, its use should enhance the effectiveness of all types of instrumentation in the area.

Another consideration is the use of ball ended inserts in a furcation area (Figure 2). This tip has a ball on its end that is about 0.8 mm in diameter. The ball-shaped tip can be adapted at the end, or its sides can be applied to the inner portions of the root (Figure 3) as well as to the concavity on the root near the furcation entrance (Figure 4). The purpose of the ballend is to adapt to the concavities of a furcation and to avoid using the point of a traditional tip on the root surface.

TREATING DEEP POCKETS

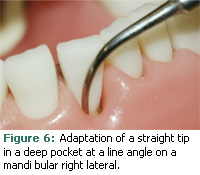

A straight tip is often used for negotiating a deep pocket in any location such as a proximal surface (Figure 5), a line angle (Figure 6), or on a buccal/facial (Figure 7) or lingual surface. The goal is to adapt the tip comfortably to the depth of the pocket using the most effective surfaces for treatment. Often, the back of the insert is adapted to the root (Figure 8). Depending on the pocket topography, a curved tip may be used.

ENDOSCOPY

Periodontal endoscopy is a visual medium used during periodontal therapy. Specifically, perioscopy is scaling and root planing that is aided by using indirect vision with an endoscope.5 Research studies have explored its use during and after initial nonsurgical periodontal therapy5-8 and have shown improved calculus removal in deeper pockets7 and reduction of histological signs of chronic inflammation.8 Its use is more common following quadrant scaling or in periodontal maintenance therapy because of reduced bleeding and inflammation, which allows for better visual acuity during the procedure. Identification of root anatomy, pathology, bacterial biofilm, calculus, dental caries, and instrumentation techniques are enhanced through the use of endoscopic imaging. Clinicians can observe the subgingival root anatomy and residual calculus following instrumentation and evaluate the clinical endpoint.

Periodontal endoscopy is a visual medium used during periodontal therapy. Specifically, perioscopy is scaling and root planing that is aided by using indirect vision with an endoscope.5 Research studies have explored its use during and after initial nonsurgical periodontal therapy5-8 and have shown improved calculus removal in deeper pockets7 and reduction of histological signs of chronic inflammation.8 Its use is more common following quadrant scaling or in periodontal maintenance therapy because of reduced bleeding and inflammation, which allows for better visual acuity during the procedure. Identification of root anatomy, pathology, bacterial biofilm, calculus, dental caries, and instrumentation techniques are enhanced through the use of endoscopic imaging. Clinicians can observe the subgingival root anatomy and residual calculus following instrumentation and evaluate the clinical endpoint.

Acquiring instrumentation skills using the endoscope requires time and effort. Approaches can be modified and new techniques or instruments adopted to successfully remove all visible deposits on roots of teeth. Some authors recommend the use of thin, diamond-coated hand activated or ultrasonic tips for final preparation of the root surface for healing.1,2 Endoscopic treatment can be provided with a one-handed or two-handed technique. The two-handed technique employs a subgingival probe with an attached fiber optic bundle that is held with the nondominant hand (Figure 9). Periodontal instrumentation is activated with the dominant hand. A neutral body position can be maintained while viewing the magnified treatment site on the video monitor throughout treatment.9

REFERENCES

- Pattison AM, Matsuda S. Making the right choice. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2003; 1(7) (Suppl):4-8.

- Matsuda S. Instrumentation of biofilm. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2003;1:26-28, 30.

- Stach D. Powering the calculus away. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2005;3(3):18-20.

- Jepsen S, Ayna M, Hedderich J, Eberhard J. Significant influence of scaler tip design on root substance loss resulting from ultrasonic scaling: a laserprofilometric in vitro study. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:1003-1006.

- Stambaugh RV. A clinician’s 3-year experience with perioscopy. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2002; 23:1061-1070.

- Avradopoulos V, Wilder R, Chichester S, Offen – bacher S. Clinical and inflammatory evaluation of perioscopy on patients with chronic periodontitis. J Dent Hyg. 2004;78:30-38.

- Geisinger M, Mealey B, Schoolfield J, Lellonig JT. The effectiveness of subgingival scaling and root planing: an evaluation of therapy with and without the use of the periodontal endoscope. J Periodontol. 2007;78:22-28.

- Wilson TG, Carnio J, Schenk R, Myers G. Absence of histologic signs of chronic inflammation fol lowing closed subgingival scaling and root planning using the dental endoscope: human biopsies—a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2008;79(1):2036-2041.

- Wu JC, Malik A. Maximize your visual acuity. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2004;2(7):30, 32-35.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2010; 8(1): 30, 32, 34-35.