BACKYARDPRODUCTION/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

BACKYARDPRODUCTION/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

The Opioid Crisis

Clinicians should be knowledgeable about the signs and symptoms of opioid use disorder in order to provide the most appropriate care to these patients.

This course was published in the April 2017 issue and expires April 2020. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the opioid crisis in the United States.

- Recognize signs and symptoms of opioid use disorder (OUD).

- Develop an oral health treatment plan for patients with OUD.

The misuse of opioids—both legal and illegal—is a growing public health problem across the United States, affecting the health, social, and economic well-being of many Americans. Opioids are a type of powerful pain reliever that impact the nervous system. They include legal prescription pain medications, such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine, and fentanyl, as well as illegal drugs, such as heroin.

In 2014, 47,055 deaths were caused by drug overdose, including 28,647 deaths specifically attributed to the overdose of opioids and other pain medications and heroin. Additionally, 2 million Americans either abused or were addicted to prescription opioids in 2014.1 Currently, about 91 Americans die every day due to opioid overdose,2 and one in four patients taking prescription opioids becomes addicted.3–5

Several factors have contributed to this epidemic of opioid misuse. One is the overprescription of opioids by medical and dental care providers for the management of pain. The US has the highest rates of opioid use, consuming 100% of the global totals for hydrocodone and 81% for oxycodone.6 Opioid medications are highly addictive. Once patients are no longer able to access prescription opioid medications, they may resort to using street drugs, like heroin, to appease their addiction. This has led to a significant increase in nontraditional heroin users.1 The growing social acceptance of taking prescription drugs for a variety of conditions and vigorous marketing by pharmaceutical companies have also increased the widespread use of opioids, which has corresponded to the growing problem with addiction.6

Due to the growing number of Americans misusing opioid medications, dental hygienists should be prepared to screen for opioid misuse, offer resources for treatment, and provide effective oral health care to this population.

OPIOID MEDICATIONS

The only natural opioid is derived from the resin of the opium poppy. It is used in the manufacturing of morphine and codeine. All other opioids are either synthetic or semi-synthetic, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, heroin, methadone, and fentanyl. These drugs can be ingested in pill form, snorted, injected intravenously, or smoked. The drugs most commonly associated with overdose are hydrocodone, oxycodone, and heroin.

Opioids depress the central nervous system, reducing the perception of pain. The chronic use of opioids is associated with an elevated risk of misuse.7 The longer patients take an opioid, the higher their tolerance becomes, requiring more of the drug to achieve the same effect.

While the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders previously separated substance abuse and substance dependence, the fifth edition combines them in a new diagnosis: substance use disorder (SUD).8 The diagnosis provides a continuum of mild, moderate, or severe SUD. To meet the SUD diagnosis, patients must demonstrate impaired control, social impairment, high-risk behavior, and/or pharmacological criteria. Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a subcategory of SUD.8

Dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter in SUD, and it plays a role in many mental illnesses. For patients deficient in dopamine receptors—especially the D2 dopamine receptor—the use of illicit drugs provides a significant reward.7,9 A 2015 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that 39% of patients with SUD also have a mental illness. Those aged 26 to 49 had the highest co-occurrence rate.9

SCREENING FOR OPIOID MISUSE IN THE DENTAL OFFICE

A thorough medical and social history should be taken on every patient at each appointment, including a question on the use of illicit or prescription medications for nonprescription use. Misuse of drugs may be related to psychological factors such as depression; self-medication; personality disorder; and poor coping skills. Social behaviors related to misuse may have cultural, societal, and interpersonal influences.7

The National Institute on Drug Abuse provides a guideline for the quick screening of drug use (Figure 1), which follows the protocol used in tobacco cessation: Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange.10 Ask the patient if it is ok to talk about drug use. Advise the patient he or she may be at risk for SUD. Assess the patient’s readiness to quit. In the dental office, assist and arrange would be covered by referring the patient to his or her primary care physician for help in accessing drug treatment.10

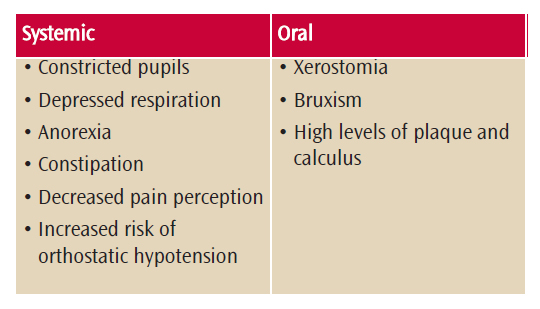

Recognizing the signs and symptoms of opioid misuse is important (Table 1).8,11 Opioids decrease pain perception, elicit moderate levels of sedation, and produce euphoria. Patients with OUD may present with constricted pupils, depressed respiration, and drowsiness. Anorexia and constipation are common side effects of opioid use. Patients using opioids are at risk for orthostatic hypotension due to the peripheral vasodilation. Dental disease in this population is typically the result of poor oral hygiene and xerostomia. Patients may present with high amounts of plaque and calculus. The risk of bruxism is also increased in this population.7,12

Patients with OUD may seek pain medication in the dental setting. Thus, oral health professionals should be aware of drug-seeking behaviors. Drug-seeking patients often call after hours and weekends complaining about pain, but claim to be visiting a friend or relative. Patients who ask for a specific medication or rebuff offers of nonopiate medications are suspect. Each state has a prescription monitoring program that health care providers can access to see how many opioid prescriptions a patient has obtained.1,13

AVAILABLE TREATMENT FOR OPIOID ABUSE

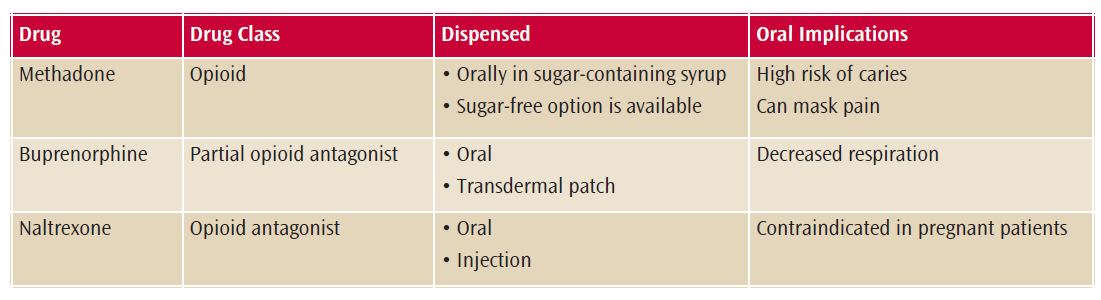

Treatment for OUD may include pharmacotherapy to help with withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Withdrawal can be very difficult and is the main reason for relapse. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is often used in conjunction with behavioral therapies. Medications designed to decrease the symptoms of withdrawal include methadone, buprenorphine, and extended-release injectable naltrexone (Table 2).14 Methadone is only dispensed in highly structured clinics, but buprenorphine may be obtained from a physician’s office.15 Buprenorphine may be combined with naltrexone or used as a transdermal patch.15 Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist that can either be given orally or by monthly injection. It is contraindicated in pregnant women and is used for highly motivated patients, as it is dependent on strict adherence to a schedule.12

Methadone is an opioid used to treat withdrawal symptoms, increase retention in drug treatment, and reduce risky behavior associated with misuse of injectable opioids. It has the potential for abuse, and methadone has been implicated in overdose deaths. Dispensed in a sugar-containing syrup, methadone use has many oral complications. A decrease in salivary flow due to the signal disruption of the parasympathetic receptors of the salivary glands increases the risk of xerostomia. This leads to higher plaque and a greater risk of buccal Class V caries of the mandibular canines and premolars. Patients on methadone have exhibited apoptosis that may result in the interruption of the normal flora of the oral cavity. These patients crave sugar, as it stimulates the receptors for the reward center in the brain, leading to a higher risk of decay. Oral manifestations of patients on MAT may experience similar oral destruction as seen in “meth mouth.” As with other opioids, methadone has an analgesic effect that may mask pain. This can lead to more severe oral conditions before the patient realizes a problem exists.11

Buprenorphine was approved in 2002 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of OUD. A partial opioid agonist, buprenorphine provides the same effects as opioids like heroin or methadone but to a lesser degree. The patient still exhibits respiratory depression and euphoria, but buprenorphine is given in a lower dose that reduces the risk of abuse and side effects. It is a long-acting agent, so patients may not have to take it every day. Buprenorphine has potential for abuse, so it is recommended for use in combination with naltrexone. Buprenorphine must be used cautiously with patients who have liver disease, and medical personnel must go through specific training in order to dispense and prescribe it.

ADDRESSING OVERMEDICATION AND OVERDOSE

Oral health professionals should be able to recognize the signs of overmedication or overdose of opiates. Overmedication has the same signs as overdose, just less severe. Patients will present with extreme sleepiness and cannot be kept awake even with loud verbal stimulus. They will exhibit mental disorientation and respiration will be shallow or depressed. Fingernails or lips may become cyanotic and pupils may be severely constricted. Bradycardia and hypotension are common with both overdose and overmedication.

If a patient shows signs of opioid overdose, naloxone can be administered. This medication binds the opioid receptors, reducing the opioid’s effects.14 Patients who are on MAT can be prescribed naloxone, especially if they are considered at high risk for opioid overdose or prescribed rotating opioid prescriptions.15 In many states, naloxone may be prescribed to a dental office in case of emergency.14 Using naloxone for the reversal of opioid overdose is an FDA-approved indication. The rate of response for naloxone is 3 minutes to 5 minutes and the duration of action is 20 minutes to 90 minutes, dependent on dose and route of administration. If the patient is in respiratory distress, rescue breathing should continue until he or is able to breath on his or her own.14 Administering a low-dose of naloxone may precipitate withdrawal symptoms. This is possible with a dose of 0.05 mg to 0.2 mg of intravenous naloxone in a patient who is taking 24 mg of methadone daily. Symptoms of withdrawal may include body aches, tachycardia, sneezing and runny nose, sweating, nausea, irritability, and increased blood pressure.

ORAL CARE CONSIDERATIONS

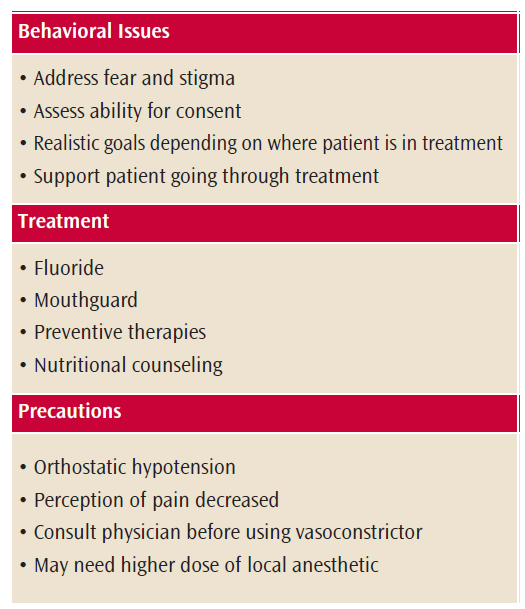

Oral health professionals must carefully consider their treatment plans when providing care to patients with OUD (Table 3).16–18Before providing care to patients currently abusing opioids, their degree of impairment must be evaluated, as this will affect their ability to give consent. Patients must be able to understand the procedure and the risks involved in dental treatment. If a patient is currently abusing opioids, stabilizing his or her oral health may be the goal until more extensive treatment can be completed. Providing provisional restorations, oral hygiene instructions, and prescription fluoride may be positive first steps so patients build a relationship with the oral health care team. Many patients with OUD demonstrate a high fear of dental procedures and needle phobias. Sedation may be an option for this population.19

Nutritional counseling is important for patients with OUD. They tend to use sugar more frequently than the general population. Generic methadone also contains sugar, increasing the risk for caries. A brand-name version of methadone is available in a sugar-free oral concentrate but it is more expensive. Prescription fluoride use may be indicated to reduce caries potential. The immune systems of patients taking methadone are hampered, increasing the importance of good oral health and nutrition. Recommending appropriate oral hygiene aids is important. Alcohol-free mouthrinse may be indicated As bruxism is more common in populations with OUD, night guards may be helpful.11,16,19 Xerostomia is also very common and should be addressed with saliva substitutes, oral care products with a neutral pH, calcium phosphate technologies, and secretagogues.

Patients with OUD may present with high levels of fear and anxiety, making adequate anesthesia imperative.16,17,19 Patients who are opioid abusers have a longer duration of onset of local anesthesia. This may require higher doses of anesthesia, especially lidocaine and bupivacaine.17 Caution should be used if administering vasoconstrictors to patients on methadone regimens. Vasoconstrictors may raise the risk of tachycardia. The patient’s physician should be consulted before using a vasoconstrictor.20

Pain management may be necessary following dental procedures. The American Dental Association published a Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain.18 These guidelines are especially important when treating patients with OUD. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications should be the first choice of post-treatment medication and opioids should be avoided completely in this population.

SUMMARY

Oral health professionals will likely provide treatment to patients with OUD. They should be prepared to recognize the signs and symptoms of OUD and adjust oral health care plans accordingly. Providing adequate pain management is also key to successful dental treatment plan in this population. Finally, clinicians need to recognize OUD and other substance abuse problems as medical conditions and provide patients with empathetic, compassionate care without judgment.

REFERENCES

- Rudd R, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved deaths—United States 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1445–1452.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER); 2016. Available at: http://wonder. cdc.gov. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, Boudreau DM, Calsyn DA. Opioid use behaviors, mental health and pain—development of a typology of chronic pain patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:34–42.

- Boscarino JA, Rukstalis M, Hoffman SN, et al. Risk factors for drug dependence among out-patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system. Addiction. 2010;105:1776–1782.

- Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Klessig CL, Mundt MP, Brown DD. Substance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapy. J Pain. 2007;8:573–582.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescrption Drug Abuse. Available at: drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Little J, Falace D, Miller C, Rhodus N. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 8th Ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2012.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available at: samhsa.gov/data. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- National Institute for Drug Abuse. Resource Guide for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. Available at: drugabuse.gov/publications/resource-guide-screening-drug-use-in-general-medical-settings/screen-then-intervene-conducting-brief-intervention. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Brondani M, Park PE. Methadone and oral health—a brief review. J Dent Hyg. 2011;85:92–98.

- Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain-United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(No RR-1):1–49.

- Denisco R, Kenna G, O’Neil M, et al. Prevention of prescription opioid abuse. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:800–810.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit. Available at: store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA16-4742/InformationforPrescribers.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatments for Substance Abuse Disorders, Available at: samhsa.gov/ treatment/substance-use-disorders#opioid. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Ma H, Shi X, Hu D, Li X. The poor oral health status of former heroin users treated with methadone in a Chinese city. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:51–55.

- Hashemian A, Omraninava A, Kakhki A, et al. Effectiveness of local anesthesia with lidocaine in chronic opium abusers. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2014;7:301–304.

- American Dental Association. Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain. Available at: ada.org/en/about-the-ada/ada-positions-policies-and-statements/statement-on-opioids-dental-pain. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- Millar L. Psychoactive substance dependence: a dentist’s challenge. Prim Dent J. 2015:4:49–54.

- Wynn R, Neukker T, Crossley H, Drug information Handbook for Dentistry 2016-2017. Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Wolters-Kluwer; 2017.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2017;15(4):32-35.