Magic of Tooth Movement

Terri Tilliss, RDH, PhD, interviews her orthodontist colleague Ricky E. Harrell, DMD, about what’s new in the world of orthodontic therapy.

The field of orthodontics has undergone significant innovation. Whether dental hygienists are interested in a career shift or

The field of orthodontics has undergone significant innovation. Whether dental hygienists are interested in a career shift or

in making the most appropriate patient referrals for orthodontic treatment, understanding the current practice of orthodontics

is an important part of comprehensive oral health care. I had the pleasure of speaking with Ricky E. Harrell, DMD, an orthodontist at the University of Colorado Denver School of Dental Medicine, about what dental hygienists need to know regarding current strategies and advances that are integral to the clinical practice of orthodontics.

Q. How do orthodontists get teeth to move?

A The “magic” of tooth movement is a process of osteoclastic bone resorption and osteoblastic bone deposition. Each tooth that needs to be moved has one side with a pressure component that stimulates bone resorption. Opposing it is the tension side of the tooth that stimulates bone deposition. With these two opposing systems at work, bone is resorbed in the direction that a tooth is moving and deposited in the area from which the tooth started. This cycle of resorption/deposition repeats itself, allowing the tooth to move at an average rate of 0.5 mm to 1 mm per month.

| Table 1. Clinical presentations that may warrant referral to an orthodontist in patients younger than 7 years.

•Premature or late loss of deciduous teeth. • Difficulty in chewing or biting. • Chronic mouth breathing. • Persistent thumb or digit habits. • Shifting of the jaw in closing to accommodate misaligned dentition. • Popping, cracking, or other joint noises upon opening or closing. • Speech difficulties. • Cheek biting upon closing or teeth impinging on soft tissue when closing. • Facial asymmetry. • Teeth that do not contact opposing teeth or meet in an abnormal way. • Persistent grinding or clenching. • Severe maxillary incisor protrusion. |

Q. What should dental hygienists look for when considering an orthodontic referral?

A The American Association of Orthodontists recommends evaluating children for existing and potential orthodontic problems at 7 years of age. However, earlier referral is warranted in certain situations. Table 1 provides examples.

Q What are fixed orthodontic appliances and removable orthodontic appliances?

A Fixed orthodontic appliances (FOAs) are semi-permanently attached to the teeth for the duration of the orthodontic treatment, including bands, bonded brackets, and other auxiliary appliances. FOAs are placed at the initiation of treatment and removed at the end of treatment; they cannot be removed by patients. On the other hand, removable orthodontic appliances (ROAs), such as retainers and headgears, can be inserted and removed by patients. They can create certain types of tooth movements and are often used as retention devices in their de-activated state (when the tooth-moving components, eg, springs, wires, etc, are not exerting a force capable of tooth movement). Aligners are another form of removable orthodontic appliances that can be used to treat certain cases.

Q How are both fixed and removable orthodontic appliances used to produce results?

A FOAs are the workhorses of orthodontic treatment regimens. They are suited for both simple and complex treatment modalities. ROAs are best suited for simple tooth movements, such as tipping the crown of a tooth. ROAs are used more frequently in younger patients with mixed dentition. They are esthetic and provide the opportunity for effective oral hygiene during the course of treatment. Downsides to ROAs include dependent on patient compliance, inadvertent breakage, and loss of the appliance, especially with younger patients. With ROAs, control over the success or failure of the treatment is shifted from practitioners to patients.

Q Please explain aligner technology.

A Aligner technology is the use of custom-fit, thin plastic trays worn over the dentition, much like a mouthguard, to align the teeth over time (Figure 4). The use of 3-D computer technology has made the use of aligner technology much simpler.

Like all removable appliances, they are dependent on patient cooperation for success. With their entrance into the orthodontic marketplace some 10 years ago, the ability to treat more difficult cases has improved dramatically. Sometimes tooth-colored auxiliaries are bonded to certain teeth to facilitate different types of tooth movement. Auxiliaries are attachments bonded to the teeth that allow the aligner trays to “grip” the tooth more effectively and thus facilitate tooth movement.

|

|

|

Q Why have bonding brackets replaced metal bands?

A Precise placement is easier with brackets, they cover less tooth surface, and they are more esthetic and hygienic. They also do not require the creation of space between the teeth with separators prior to placement. With the advent of more advanced, light-cured bonding adhesives over the past several decades, their bond strength to the teeth is equal or better than that of bands. Many practitioners, however, still prefer to band molars and some premolars because of the chewing pressures exerted in the posterior areas of the mouth.

Molar-bonded brackets are subject to dislodgement or breakage because the chewing pressures in an adult can approach 20,000 pounds per square inch, and the bonding adhesives cannot withstand that amount of pressure without fracturing. Some bands also have excellent lingual attachments that are useful for attaching elastics and auxiliary appliances.

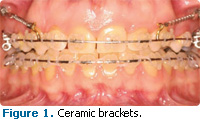

Q What are ceramic brackets?

A Ceramic brackets are a type of esthetic bracket commonly used in contemporary orthodontic treatment (Figure 1). They are placed on the facial or buccal surface of the dentition. Generally they are made of a tooth-colored or clear polycrystalline material. They function just like traditional metal brackets and, in most cases, can provide the same treatment results. Ceramic brackets are most commonly selected for esthetic reasons and when a patient has a known nickel allergy, although this is rare.

|

|

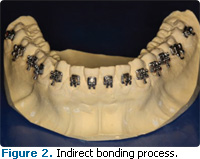

Q What is the difference between indirect bonding and direct bonding?

A Indirect bonding is a process by which brackets are bonded to the teeth simultaneously. An impression and stone model of the teeth are manufactured prior to the bonding appointment. The brackets are situated on the stone model with a temporary luting agent and a soft tray is vacuum-formed or pressure-formed over the brackets. When the tray is removed, the brackets are embedded in the soft tray (Figure 2). At the bonding visit, the patient is made ready for bonding with a pumice, acid etch, and monomer placement and curing. Adhesive is applied to the brackets within the soft tray, the soft tray is seated over the dentition, and the adhesive is light-cured through the tray. The soft tray is then removed, leaving the brackets in place on the teeth.

Direct bonding does not require any laboratory work. The teeth are pumiced and etched; the monomer is placed and cured; adhesive is applied to the base of the bracket; the bracket is placed in the appropriate location on the tooth; and the composite is cured. Indirect bonding works in patients who need most of their teeth bonded. Direct bonding is preferable in mixed dentition or when only a limited number of teeth need brackets.

Q What are lingual braces?

A Lingual braces are fixed appliances that are bonded to the lingual surfaces of the teeth in both arches (Figure 3) to improve esthetics. They are not seen easily in the course of conversation or smiling. Lingual braces are generally more expensive and more difficult to manipulate. Due to the difference in bracket location on the teeth, they require alternative methods of instrumentation. Lingual appliances are contraindicated in most surgical cases and they may cause soft tissue irritation and speech impairment.

Q Describe the development of NiTi wires.

A The term “NiTi” indicates arch wires made of nickel-titanium alloy. The wires have excellent flexibility, a low load-deflection rate (the pressure exerted when a wire is bent), have minimal allergic reactivity, and can be manufactured in different gauges, shapes, and cross-sections. NiTi wires are capable of delivering very low pressure when deformed over a long period of time. This means they do not have to be changed on a monthly basis if they are still active. They are used in all stages of orthodontic treatment.

Q When are temporary anchorage devices indicated?

A Temporary anchorage devices (TADs) are also referred to as mini-screw implants, mini dental implants, and orthodontic implants. The first type of TAD uses bone screws or miniscrews that range in length from 6 mm to 12 mm and are 1.4 mm to 2.0 mm in diameter (Figure 5).

TADs are used as anchors for other orthodontic treatment modalities to facilitate tooth movement, especially in complex cases. TADs do not osseointegrate like traditional dental implants and they are removed after treatment is completed. This type of TAD can be placed most often with topical anesthesia. The other type of TAD is a skeletal anchorage system that is held into bone with tiny screws and an attachment that protrudes through an incision into the oral cavity. This TAD is anchored in cortical bone, either in the dental alveolus, palate, retromolar pad area, ascending ramus, or maxillary tuberosity, and it allows certain teeth to become immobilized so they can be used as anchors against which other teeth can be pulled or pushed. The TAD skeletal anchorage plates can also be used as anchors against which teeth can be directly pulled toward or pushed away. They are often used for retraction of anterior teeth, protraction of posterior teeth, intrusion of teeth, and when the whole dento-alveolar process is to be moved.

The placement of skeletal anchorage system devices requires a surgical procedure with an incision, reflection of a full thickness flap, placement onto the bone, and then suturing the flap back into place. An additional surgery is required to remove the device when treatment is completed. Skeletal anchorage system devices are generally placed by oral surgeons and periodontists, whereas the miniscrews are often placed in the orthodontic office by an orthodontist.

The use of both types of TADs has expanded the scope of orthodontic treatment, sometimes even eliminating the need for orthognathic surgery. Oral hygiene around TADs is particularly important because inflammation and infection are both possibilities. The mini-implants, due to their penetration through either the attached gingiva or free mucosa, serve as a conduit for bacteria to reach areas that are normally sterile, such as periosteum, cortical bone, and medullary bone. Because the soft tissue does not attach to the implant, this pathway for bacteria exists throughout the implant’s life in the oral cavity, so it is critical that the area be kept clean. Reinforcement of good oral hygiene practices in addition to checking for mobility at routine care visits is advised.

Q. What are rapid palatal expansion

A Rapid palatal expansion appliances (RPEs) are either toothborne (Hyrax expander) or both tooth- and tissue borne (Haas expander) fixed appliances that are designed to open the mid-palatal suture on growing patients to increase the width of the maxillary arch. There are different versions of each but they all feature an expansion screw, normally located in the midline of the appliance, which increases the width of the screw and appliance, thereby, over a short period of time, opening the mid-palatal suture and increasing the arch width. They are most often used to correct significant posterior crossbites. RPEs can affect true orthopedic changes during the course of orthodontic treatment. Usually the appliance is anchored to the permanent first molars in the maxillary arch as well as the first bicuspids. They are most commonly used in late mixed dentition and early permanent dentition in growing patients.

Q There seem to be several philosophies used in orthodontics. What is the thinking behind the most significant?

A There are, indeed, a number of different types of orthodontic philosophies currently used. The two main groups are those that attempt to treat almost all cases without extracting permanent teeth, such as the Damon philosophy. The other philosophical group includes extraction of permanent teeth as a part of the orthodontic treatment regimen, such as the Roth technique.

The various subgroups, eg, McLaughlin-Bennett-Trevesi, Alexander, and Andrews, are named for the doctor who designed the appliance. With the appliance design comes a technique associated with using the particular appliance as well as an overall philosophy about treatment. The various philosophies have their strong points as well as their weaknesses but all are capable of producing excellent orthodontic results in the hands of competent practitioners.

Q Does orthodontic treatment lead toroot resorption?

A Any orthodontic tooth movement, whether it is in children, adolescents, or adults, can lead to root resorption. It is generally unpredictable and usually, although not always, insignificant in the patient’s overall dental health. If it is severe and the crown/root ratio moves below 1:1, stability becomes an issue, especially if it is accompanied by periodontal bone loss. Factors commonly associated with root resorption include heavy orthodontic forces, prolonged orthodontic treatment, excessive amounts of tooth movement, injury to a tooth either prior to or during orthodontic treatment, certain endocrine disorders, and possibly age. There is no magic bullet to prevent root resorption. Patients should be informed of the possibility of root resorption before orthodontic therapy is started, periodic radiographs should be taken during treatment to monitor its occurrence, and patients and their referring dentists should be notified if root resorption does occur.

Q What does the future hold for the field of orthodontics?

A There are several trends in orthodontics that are greatly impacting the delivery of orthodontic care. First, with the increase in the number of adults receiving orthodontic care, the emphasis on esthetic appliances has never been greater. As Baby Boomers age and enjoy their prosperity, we will see greater numbers of older adults receiving orthodontic treatment and they will demand that their appliances be esthetically pleasing. Second, we will see the scope of what is possible with orthodontic treatment expand as the use of TADs becomes more widespread. Pre-prosthodontic tooth movements that were once impossible are now becoming routine with TADs. The demand for fixed prostheses among adults will increase. The use of diode lasers in orthodontic offices will increase. Digital radiography will become the standard of care over the next 10 to 20 years and 3-D imaging will become more mainstream in the orthodontic realm.

I also think we will see, due to changing economic conditions, more competition among practitioners for orthodontic patients. Practices will become more niche-oriented as they compete for patient dollars. The future is bright for orthodontics and its practitioners. It has evolved for a thousand years and will continue to do so in its quest to deliver better care.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2011; 9(4): 32, 34-36.