This course was published in the May 2011 issue and expires May 2014. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the local factors that play a role in the success of implant therapy.

- Discuss the research regarding periodontal diseases and the success of implant therapy.

- Explain the role of reduced bone volume, genetics, occlusal trauma, and systemic factors in the risk of implant complications and failure.

- List strategies for reducing the risks of implant complications and failure.

Because of implant therapy’s high success rates, patients are more accepting of implants as a treatment for missing or compromised teeth. However, implant therapy does have inherent risks for complications and failure. Research shows failure rates average between 5% and 10%.1

Biological complications refer to implants that are surviving in the patient’s jaw but are compromised by soft tissue inflammation, bone loss, or pain. Although these fixtures are not mobile, patient comfort and long-term prognosis may be problematic. Mechanical complications include problems with the prosthesis that the implant supports.

A mobile implant is an implant failure, (ie, the implant was surgically placed but did not survive). For most failed implants, failure occurs early and is often noted when the surgeon removes the healing screw or an attempt is made to restore the fixture. The basic cause of early implant failure is the inability of the implant to successfully integrate with the surrounding bone. Late failure refers to implants that are restored and functioning for a limited time period. In these cases, osseointegration may have been partial or complete. Over time, various factors may facilitate deintegration, resulting in mobility.

LOCAL FACTORS

Local factors, such as bone quality and bone volume, play key roles in implant success. Implants may have a higher success rate in cortical bone (hard outer layer) than trabecular bone (more porous).2 Another important consideration is the reason the tooth needs replacement. Teeth may be lost due to: periodontal diseases, caries, trauma, or they may be congenitally missing. Analysis of the missing dentition is helpful in case selection for implant therapy. The process that facilitated tooth loss or lack of tooth development may impact the morphology and physiology of the local anatomy designated for possible implant placement.

POOR PLAQUE CONTROL AS A RISK FACTOR

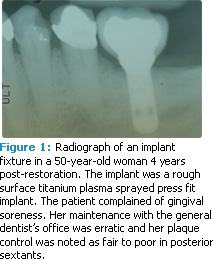

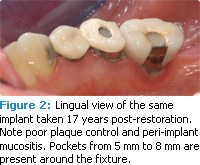

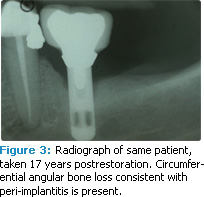

Peri-implant mucositis can develop from poor plaque control (see Figures 1-3).3,4 Bacteria associated with peri-implant mucositis is similar to the microbiota related to gingivitis. In addition, the microbiota associated with periimplantitis is similar to periodontitis.5 Reduction of implant-associated biofilm via good plaque control and professional maintenance can reduce the risk of soft tissue inflammation. When plaque control is poor and appropriate maintenance is not achieved, the risk for bone loss around the implant increases.6

Implant-supported prostheses that are difficult to clean result in increased risk of periimplant tissue inflammation and marginal bone loss. To reduce this risk, the prosthesis should be simple to clean and maintain. For a multiple unit fixed or removable prosthesis, cleansable embrasure areas should be incorporated.7

Another concern is the cementation process. Most implant supported-restorations today are cement retained. Subsequent to cementation of a crown over an abutment, care must be taken to remove excess subgingival cement. If this material is left in place, it will be plaque retentive. The excess subgingival cement may also irritate the soft tissues resulting in discomfort for the patient.

PERIODONTAL DISEASES

Hirshfeld and Wasserman originally found that even with appropriate treatment, some patients were refractory to periodontal therapy.8 Nevins and Langer were the first to try to allay fears about placing implants in patients with a history of refractory periodontitis.9 In a series of case reports, Nevins and Langer noted a high rate of implant survival in patients who had a history of being refractory to periodontal therapy. The observation period, however, for all implants placed in these studies was less than 8 years with an average of 4 years.

Mengel and colleagues reported on periimplant health and implant survival in partially edentulous patients treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAgP).10 Compared to partially edentulous controls with a healthy periodontium, GAgP subjects showed significantly more peri-implant bone loss in the first year and in the subsequent 9 years. Moreover, implant survival rates among GAgP subjects were 17% lower than survival rates in the periodontally healthy controls. The conclusion was made that although implants have a relatively high survival rate in patients treated for GAgP, there is an increased risk of implant complications.

CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS

The concern that the same microbial/host interactions that facilitate bone loss around a tooth can result in bone loss around an implant has merit.11 Periodontal diseases that result in significant bone loss usually affect dentition that has been in the oral cavity for more than 10 years. Most studies regarding implant success are conducted over a shorter time. What needs to be considered is the potential impact of implant-associated biofilm on the periimplant tissues over a period longer than 10 years to 15 years. Investigations have reported that a percentage of the population is more susceptible to periodontal attachment loss in the presence of less than optimal plaque control. With the exception of cases involving aggressive periodontitis, it can take years for these patients to develop periodontitis.

Does a partially dentate patient with periodontal bone loss have a higher risk for periimplantitis/implant loss than a patient with a healthy periodontium? Hardt, in a 5-year retrospective study, and Karoussis, in a 10-year prospective study, reported overall high success rates for implant survival.12,13 However, they also observed a 5% decrease in implant survival for individuals with a history of periodontitis compared to implants placed in those with a healthy periodontium. Marginal bone loss associated with the implants over time was generally low but the prevalence was significantly higher in individuals with a history of periodontitis.

In an investigation with 9 years to 14 years of follow-up, Roos-Jansåker and colleagues also compared implant survival rates in patients with and without a history of periodontitis. Supportive periodontal/peri-implant care was not uniform in this study, nor was it provided by the investigators. The implant failures in this report were clustered in a small group of patients who had periodontal bone loss associated with their remaining dentition. The authors concluded that implant failure was related to a history of periodontitis.14

In a subsequent report on the same patient pool, Roos-Jansåker and colleagues reported that after 9 years to 14 years, 48% of the implants had probing depths greater than 4 mm and mucositis. Approximately 8% of the implants presented with progressive bone loss and 16% had bone loss greater than 3 mm apical to the implant shoulder. A significant relationship between the observed peri-implantitis and a history of periodontitis was noted. The authors’ conclusion was that after 10 years in function without systematic supportive treatment, peri-implant lesions are common.15

Although this research indicates a relationship between implant complications/failure for patients with periodontal bone loss, a clear investigation of periodontal disease activity was not presented. In other words, bleeding on probing, microbial sampling, probing depths, and advancing clinical attachment loss were not consistently analyzed relative to the reported implant complications/loss. Research conducted on implants placed in patients with periodontal bone loss should include a description of periodontitis management.

The presence of residual pockets post-periodontal therapy is a problem. These pockets may serve as a reservoir for infection of periimplant issues.16 Moreover, if implants are placed in a patient with pockets, the therapist should resolve any inflammation that may be present and eliminate any subgingival calculus on the teeth adjacent to the implant site. Pockets associated with radiographic horizontal bone loss are not the same as pockets related to radiographic angular defects. Pockets associated with vertical osseous loss are infrabony defects. Left untreated, these teeth are at an increased risk of continued attachment loss.17 Progressive bone loss around teeth adjacent to an implant fixture is not only a concern to the involved dentition but should also be a concern for the prognosis of the adjacent implant.

Further research is needed to determine if, for some patients with peri-implant mucositis, peri-implantitis develops after long-term exposure to pathogenic biofilm.18 For the present, it is prudent to assume implant-associated plaque may develop into a more pathological and peri-implant disease-causing microbiota. Dental professionals and their patients should be cautioned that long-term exposure to a more pathological plaque could result in peri-implantitis and possible implant loss. Reduction of this risk can be achieved via an individualized maintenance program designed to reduce the level of plaque for the peri-implant and periodontal tissues of the partially edentulous patient.19 Moreover, an appropriate implant maintenance program is logical for the edentulous patient treated with implants.

REDUCED BONE VOLUME

GENETICS

The genetic marker most evaluated for periodontitis is a polymorphism for the cytokine IL-1. In particular, an IL-1 B is linked with bone loss associated with periodontal diseases. For some patients, genetic susceptibility may play a role in developing implant complications. Investigators have also evaluated IL-1 polymorphism related to implant complications survival. The evidence is growing that a variation of the cytokine IL-1 may play a role.21

TRAUMA FROM OCCLUSION

Parafunctional habits or bruxism can put additional stress on the natural dentition beyond the normal forces of mastication. The same is true for implant-supported restorations. If forces associated with occlusal overload are generated into the bone implant interface, marginal bone loss may occur.22 Continued bone loss could result in deintegration of the implant. To prevent this situation, occlusal schemes must be carefully constructed with smaller occlusal tables and no contact in lateral or anterior excursions. In addition, patients may benefit from night guards.

SYSTEMIC RISKS

Chronic inflammation associated with implant fixtures has been observed in smokers. Bain and Moy reported an 11% failure rate in smokers compared to 5% among nonsmokers.23 Wilson and colleagues also reported an increased risk of implant loss among smokers compared to nonsmokers.24 Tobacco users should be advised to reduce exposure or quit all together to improve outcomes. The use of a smoking cessation protocol may increase the implant survival rate.25

Diabetes is also associated with lower implant survival rates. Chronically high levels of glucose in the blood can result in increased production of inflammatory mediators and decreased neutrophil function. Chronically high levels of glucose in the blood over a 90-day period can be detected with a HbA1C test, which identifies how the patient has been managing his or her blood glucose levels. Typically, HbA1C levels of seven or less are described as controlled diabetes. Among patients with HbA1C values higher than seven, Fiorellini and colleagues noted a 14% implant failure rate over 5 years.26 Tawil and colleagues also reported implant success rates in people with controlled diabetes averaging HbA1C values of 7.2 similar to patients without diabetes.27 These findings suggest that patients with type 2 diabetes can be successfully treated with implant therapy provided they properly manage their diabetes.

Osteoporosis is associated with a reduction in bone mass and has been examined as a risk factor for implant complications/failure. Recently, bisphosphonate therapy for the prevention and reduction of osteoporosis has been a significant concern for dental extractions as well as surgical implant therapy.28 These medications have been linked to poor healing, which can result in bone necrosis. Patients taking bisphosphonates should be advised of this risk when considering oral surgical procedures including implant therapy. In some instances, a “drug holiday” is recommended where the medication is stopped in order to reduce the risk of bisphosphonate-induced necrosis of the jaws.

Radiation therapy to the jaws is used in the treatment of cancer and it increases the risk of osteoradionecrosis when surgery is performed for dental extractions or for implant placement. Successful outcomes can be achieved with these patients, however, radiation dose, field, and type of radiation treatment must be evaluated.29

SUMMARY

Implant therapy is a predictable treatment option for the replacement of missing teeth. Complications and failure, however, can and do occur. Patients who are considering dental implant therapy should be advised of the potential for implant complications/ failure. Appropriate case selection can be facilitated by carefully evaluating risk factors.

The implant treatment plan should include appropriate concomitant periodontal therapy for the remaining dentition and an individualized maintenance program. Recommendations for proper oral hygiene, smoking cessation, and successful management of diabetes should also be provided.

REFERENCES

- Berglundh T, Persson L, Klinge B. A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry reported in prospective longitudinal studies of at least 5 years. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:197-212.

- Jaffin RA, Berman CL. The excessive loss of Branemark fixtures in type IV bone: a 5-year analysis. J Periodontol. 1991;62:2-4

- Schou S, Holmstrup P, Stoltze K, Hjørting-Hansen E, Kornman KS. Ligature-induced marginal inflammation around osseointegrated implants and ankylosed teeth. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1993;4:12-22.

- Zitzmann NU, Berglundh T, Marinello CP, Lindhe J. Experimental peri-implant mucositis in man. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:517-523.

- Mombelli A, van Oosten MA, Schurch E Jr, Land NP. The microbiota associated with successful or failing osseointegrated titanium implants. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:145-151.

- Ferreira SD, Silva GL, Cortelli JR, Costa JE, Costa FO. Prevalence and risk variables for peri-implant disease in Brazilian subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:929-935.

- Serino G, Ström C. Peri-implantitis in partially edentulous patients: association with inadequate plaque control. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:169- 174.

- Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B. A long-term survey of tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1978;49:225-237.

- Nevins M, Langer B. The successful use of osseointegrated implants for the treatment of the recalcitrant periodontal patient. J Periodontol. 1995;66:150-157.

- Mengel R, Behle M, Flores-de-Jacoby LJ. Osseointegrated implants in subjects treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis: 10-year results of a prospective, long term cohort study. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2229-2237.

- Meffert RM. Periodontitis and periimplantitis: one and the same? Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1993;5:79-82.

- Hardt CR, Gröndahl K, Lekholm U, Wennström JL. Outcome of implant therapy in relation to experienced loss of periodontal bone support: a retrospective 5-year study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:488-494.

- Karoussis IK, Salvi GE, Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Bragger U, Hammerle CH, Lang NP. Long-term implant prognosis in patients with and without a history of chronic periodontitis: a 10-year prospective cohort study of the ITI Dental Implant System. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:329-339.

- Roos-Jansåker AM, Renvert H, Lindahl C, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow-up of implant treatment. Part I: factors associated with peri-implant lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:283-289.

- Roos-Jansåker AM, Renvert H, Lindahl C, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow-up of implant treatment. Part III: factors associated with periimplant lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:296-301.

- Gouvoussis J, Sindhusake D, Yeung S. Crossinfection from periodontitis sites to failing implant sites in the mouth. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1997;12:666-673.

- Papapanou PN, Wennström JL. The angular bony defect as an indicator of further alveolar bone loss. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:317-322.

- Heitz-Mayfield LJA. Peri-implant diseases: diagnosis and risk indicators. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(Supp):292-304.

- Wennström JL, Ekestubbe A, Gröndahl K, Karlsson S, Lindhe J. Oral rehabilitation with implant supported fixed partial dentures in periodontitissusceptible subjects A 5-year prospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:713-724.

- Tonetti MS, Hämmerle CH, European Workshop on Periodontology Group C. Advances in bone augmentation to enable dental implant placement: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8 Suppl):168-172.

- Laine ML, Leonhardt A, Roos-Jansåker AM, et al. IL-1RN gene polymorphism is associated with periimplantitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:380-385.

- Misch CE, Suzuki JB, Misch-Dietsh FM, Bidez MW. A positive correlation between occlusal trauma and peri-implant bone loss: literature support. Implant Dent. 2005;14:108-116.

- Bain CA, Moy PK. The association between the failure of dental implants and cigarette smoking. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1993;8:609-615.

- Wilson TG Jr, Nunn M. The relationship between the interleukin-1periodontal genotype and implant loss. Initial data. J Periodontol. 1999;70:724-729.

- Bain CA. Smoking and implant failure—benefits of a smoking cessation protocol. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1996;11:756-759.

- Fiorellini J, Chen P, Nevins M, Nevins ML. A retrospective study of dental implants in diabetic patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2000;20:366-373.

- Tawil G, Younan R, Azar P, Sleiati G, Conventional and advanced implant treatment in the type 2diabetic patient: Surgical protocol and long-term clinical results. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2008;23:744-752.

- Marx RE, Cillo JE Jr, Ulloa JJ. Oral bisphosphonateinduced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2397-2410.

- Ihde S, Kopp S, Gundlach K, Konstantinović VS. Effects of radiation therapy on craniofacial and dental implants: a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:56-65.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2011; 9(5): 60-63.