Follow the Evidence

Dental hygienists need to adhere to evidence-based polishing protocols when performing this common procedure.

Appropriate polishing techniques backed by scientific evidence are widely discussed in journals and textbooks.1–7 The science of abrasion is not new, and it serves as the basis of the most effective procedures for polishing teeth and restorations to remove stain and dental biofilm without removing enamel. With no scientific evidence to support the theory of selective polishing, this technique is no longer recommended.8

Unfortunately, many dental hygienists use the same polishing paste on every patient, regardless of the grit size and the patient’s needs. Even worse is the fact that many dental hygienists subscribe to the “coarse grit theory,” which encourages the use of coarse polishing paste on every patient to remove the entire range of stain—from light to heavy—in order to save time. This theory goes against the professionally recommended, evidence-based method of using polishing paste grits in a progression of coarse grit to medium grit to fine grit.

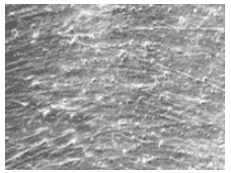

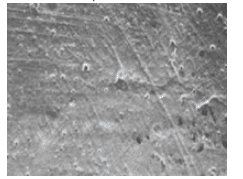

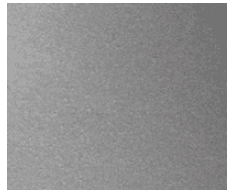

Coarse grit polishing pastes may remove stain quickly, but this comes at a price. They can produce dentinal hypersensitivity, roughen tooth surfaces, and accelerate staining and the retention of dental plaque and calculus. Further, coarse-grit polishing can damage the integrity of both esthetic and functional restorations. Structurally, the restoration is left vulnerable to dental biofilm retention and, thus, decay. The use of coarse, medium, and fine grit polishing pastes can also remove the resin and expose the filler particles of esthetic restorations.9–11 Additionally, the esthetic restoration is left with deep irregular scratches—a perfect environment for stain and dental biofilm to accumulate. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the circular scratches caused by polishing. Figure 3, a finished hybrid composite, is used as a control for comparison.

The practice of coarse-grit polishing is widespread in dental hygiene as demonstrated by the high sales of coarse grit polishing paste. Among polishing pastes sold in the United States, 80% are coarse grit and 10% are medium grit.12 The sales numbers for coarse grit polishing pastes have not changed in more than 30 years.12 Dental hygienists need to commit to lifelong learning as health care professionals and follow the best evidence available.

AN INTEGRAL PART OF THE ORAL PROPHYLAXIS

Polishing is an integral procedure in the delivery of oral prophylaxis.13,14 While the process of polishing appears mundane, it involves several complex issues—many of which are interdependent. The polishing of teeth and dental restorations is important for patient satisfaction and success in the prevention and treatment of oral disease.

The American Academy of Periodontology defines oral prophylaxis as the “removal of plaque, calculus, and stain from exposed and unexposed surfaces of the teeth by scaling and polishing as a preventive measure for the control of local irritational factors.”15 A white paper on oral prophylaxis published by the American Dental Hygienists’ Association states, “Oral prophylaxis should consist of supragingival and subgingival removal of plaque, calculus, and stain.”16

Polishing produces smooth surfaces on the teeth and restorations, thereby reducing the adherence of dental plaque, extrinsic stains, and calculus. From the patient’s perspective, the removal of extrinsic stains from teeth and restorative materials enhances esthetics. Patients expect to have their teeth polished when they have their teeth “cleaned,” and they expect to get that “smooth” feeling upon completion of the prophylaxis appointment.

Appropriate polishing depends on the progression from coarse to fine polishing pastes. If the patient requires coarse grit polishing paste for the tooth surfaces, the teeth should be repolished with medium grit paste followed by repolishing with fine grit paste. If the patient has stain that can be removed with medium grit polishing paste, the teeth should then be repolished with fine prophylaxis polishing paste. If fine grit polishing paste is routinely used, medium or coarse grit pastes will only be needed for heavy stain removal. Starting out with fine grit polishing paste in all cases is logical. If the fine paste removes the stain, then the repolishing steps can be avoided.

Another polishing material that is appropriate for all tooth and restorative surfaces is a cleaning agent. The cleaning agent currently on the market is a powder that must be mixed with water or neutral sodium fluoride. A cleaning agent will not scratch tooth or restorative surfaces. It is ideal for patients without stain but who want their teeth polished.

POLISHING ESTHETIC DENTAL RESTORATIONS

Esthetic, tooth-colored dental restorations are often undetectable. Therefore, prior to polishing, the patient’s mouth should be carefully examined and his or her chart and radiographs consulted for the location of esthetic dental restorations. These restorations can be highly damaged by coarse grit polishing paste, even after one exposure.17 If the patient’s chart indicates the brand of the esthetic restoration, the dental hygienist should consult the manufacturer’s directions for polishing. There are several polishing products that will not harm esthetic dental restorations. Moreover, a cleaning agent can be used to clean restorations without harming their integrity.

CONCLUSION

Polishing teeth and dental restorations is an important part of the oral prophylaxis and should not cause harm. Polishing requires knowledge of the hard dental tissues, dental restorative materials, and the science of abrasion. Polishing teeth and restorations only with coarse grit polishing pastes is highly unethical. Dental hygienists need to follow the scientific evidence so they can provide the highest standard of care.

REFERENCES

- Barnes CM. The science of polishing. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2009; 7(11):18–20,22.

- Pence SD, Chambers DA, van Tets IG, Wolf RC, Pfeiffer DC. Repetitive coronal polishing yields minimal enamel loss. J Dent Hyg. 2011;85:348–357.

- Essex G. Predilection for polishing. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2005;3(3):36,38.

- Beebe SN. To polish or not to polish? Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2009;7(3): 32,35.

- Pence S. Polishing particulars. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(6): 24,26,28.

- Bertoldo C, Lima D, Fragoso L, Ambrosano G, Aguiar F, Lovadino J. Evaluation of the effect of different methods of microabrasion and polishing on surface roughness of dental enamel. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25:290–293.

- Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Forthcoming June 2016.

- Barnes CM. Shining a new light on selective polishing. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2012;10(3):42–44.

- Barnes, CM. Polishing esthetic restorative materials. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2010;8(1):24,26–28.

- Jeffries SR. Abrasive finishing and polishing in restorative dentistry: a state of the art review. Dent Clin N Am. 2007;51:379–397.

- Neme AL, Frazier KB, Roeder LB, Debner TL. Effect of prophylactic polishing protocols on the surface roughness of esthetic restorative materials. Oper Dent. 2002;27:50–58. 12. Strategic Data Marketing. Available at: sdmdata.com. Accessed October 4, 2015.

- Strategic Data Marketing. Available at: sdmdata.com. Accessed October 4, 2015.

- Barnes CM. Extrinsic stain removal. In: Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 2013:689–708.

- Guideline on the role of the dental prophylaxis in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2007-2008;29(Suppl 7):1–271.

- Glossary of Periodontal Terms. 4th ed. Chicago: American Academy of Periodontology. 2001:42.

- American Dental Hygienist’s Association. Position Paper on the Oral Prophylaxis. Available at: adha.org/profissues/prophylaxis.htm. Accessed October 4, 2015.

- Barnes CM, Covey D, Walker MP, Johnson WW. Essential selective polishing: the maintenance of aesthetic restorations. J Prac Hyg. 2003;12:18–24.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2015;13(11):36,38.