ETERNALCREATIVE/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

ETERNALCREATIVE/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Ethical Decision Making in Dental Hygiene

Clinicians face ethical dilemmas throughout their careers, but a strong educational foundation in ethics and ethical decision-making provides a helpful guide.

This course was published in the May 2017 issue and expires May 2020. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Differentiate between ethics and clinical ethical dilemmas.

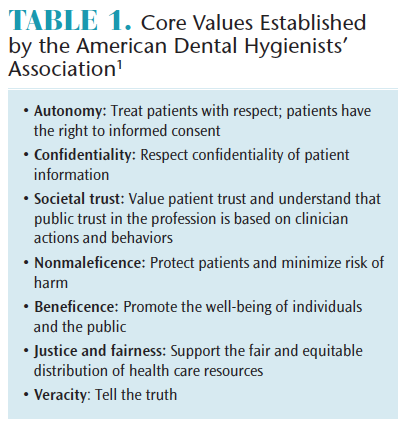

- List and define the American Dental Hygienists’ Association’s core values.

- Discuss the evolution of ethics education.

- Identify the six steps in applying an ethical decision-making model.

Within the discipline of philosophy, ethics is the branch that focuses on morality. Ethics is concerned with studying human behavior and the principles that regulate it.1 Many theories describe ethics and moral reasoning, but when individuals are asked to define ethics, most respond with a version of “doing the right thing.” The core values established by the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) are designed to help practitioners “do the right thing.” Table 1 lists these core values.1

Ethical dilemmas arise when one or more ethical principles or core values are in conflict.2For example, a patient requests a 12-month recare schedule due to financial difficulties (autonomy), but the dental hygienist believes that 4-month appointments are what the patient needs to improve his oral health (beneficence). Different ethical decisions can be made regarding the same ethical dilemma, resulting in no right or wrong conclusion. In some instances, compromises can be made, such as agreeing on a 6-month recare for the example above. In other cases, there is no compromise and a decision must be made. Dental hygienists face ethical dilemmas and perhaps even legal issues throughout their careers, but a strong educational foundation in ethics and ethical decision-making can help guide their actions and behaviors.

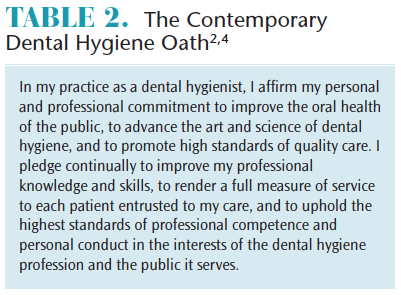

The topic of ethics is engrained in dental hygiene students from matriculation through graduation. In most dental hygiene programs, the dental hygiene oath is either recited during a matriculation ceremony, graduation ceremony, or both. What is taught in between these ceremonies is designed to help students understand what the oath really means.

The dental hygiene oath was originally adopted by the ADHA in 1948 and included a reference to Alfred Fones, DDS—the founder of the dental hygiene profession.3 The modern version of this oath was adopted by ADHA Board of Trustees in 1979.2,4 Although the word “ethics” or “ethical” is not specifically mentioned in the dental hygiene oath, dental hygienists have an ethical and moral obligation to uphold the oath and maintain high professional standards. Because dental hygienists are health care professionals, they have a professional responsibility to practice in an ethical manner.

Many documents reinforce this ethical practice directive. The ADHA maintains a Code of Ethics for Dental Hygienists that was revised and re-adopted in June 2016.1 This document specifically delineates its purpose, key concepts, basic beliefs, fundamental principles, core values, and standards of professional responsibility. The objectives of this code are to:1

- Increase dental hygienists’ professional and ethical consciousness and sense of ethical responsibility.

- Lead dental hygienists to recognize ethical issues and choices and to guide them in making more informed ethical decisions.

- Establish a standard of professional judgment and conduct.

- Provide a statement of ethical behavior the public can expect from dental hygienists.

The ADHA published a second document, Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice, which was also revised in 2016. The standards state, “Dental hygienists are responsible and accountable for their dental hygiene practice, conduct, and decision making. Throughout their professional career in any practice setting, a dental hygienist is expected to understand and adhere to the ADHA Code of Ethics.”5

Lastly, the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA)—the agency that establishes and applies standards to ensure quality in dental-related education—states in Standard 2-19, “Graduates must be competent in the application of the principles of ethical reasoning, ethical decision making, and professional responsibility, as they pertain to the academic environment, research, patient care, and practice management. Dental hygienists should understand and practice ethical behavior consistent with the professional code of ethics throughout educational experiences.”6

Dental hygiene programs have added individual courses in ethics and/or embedded ethical principles throughout the curricula in both didactic and clinical courses to meet this standard. These three documents help guide the education and training that dental hygiene students receive in their respective programs throughout the country, to pass their national board examinations, obtain licensure, and become competent dental hygiene professionals.

EVOLUTION OF ETHICS EDUCATION

The emphasis on ethics in dental hygiene education resulted from the growing body of evidence demonstrating that ethical issues were occurring in the profession and better preparation to address these issues was needed. Several studies were conducted in the 1980s on how ethical instruction was taught in dental hygiene curricula. Kacerik et al7 concluded that traditional methods of instruction were primarily used and real-life experiences should be emphasized to a greater degree. Jong8 and Heine determined that ethics was taught mainly using a lecture format, but that many programs were combining lecture with more active forms of learning, such as the use of ethical dilemmas.

In 1990, a survey of ethical issues among dental hygienists was conducted.9 This survey evaluated the type and frequency of ethical issues encountered and asked the participants about the education they received in ethical theory and problem solving. Interestingly, the authors found 86% of respondents received instruction in ethical theory, but only 51% stated they received instruction in solving ethical problems. Therefore, the authors concluded that the majority of respondents encountered serious ethical dilemmas in their practices and as a result, found that entry-level education should include more education in solving ethical dilemmas.9

In 2006, a study was conducted among graduating dental hygiene students to determine their attitudes toward specific ethical dilemmas.10 The findings indicated that many dental hygiene students did not understand their ethical role in addressing behaviors in the practice environment. The respondents felt that dental hygienists had a strong duty to report, intercede, or educate in areas of abuse, sexual harassment, detection of cancer, and smoking cessation. However, they were less likely to report issues such as fraud, inadequate infection control, exceeding practice scope, and failure to diagnose disease when these incidences could potentially affect their employment. The authors concluded that dental hygiene programs should look for ways to improve students’ comprehension of numerous ethical issues.

In 2013, a study at the University of Minnesota looked at the effectiveness of changes made to its curriculum.11 These changes included adding new courses and updating others in an effort to enhance professional identity and responsibility. The author concluded the changes made in the curriculum were effective.11

Not only did dental hygiene curricula change as a result of the importance of ethics education, a category of “Professional Responsibility” was added to the National Board Dental Hygiene Examination (NBDHE) in 2005. Currently, the NBDHE consists of 350 questions, and 18 specifically focus on professional responsibility, including ethical principles, informed consent, regulatory compliance, and patient and professional communication.12

Due to this focus on the teaching of ethics in dental hygiene programs, current ethics education has transitioned from primarily lecture format to more case-based and discussion methods that enhance student learning.13 It is important to work through ethical scenarios in dental hygiene education using ethical decision making so that clinicians are prepared to solve ethical dilemmas when they arise.

APPLYING THE MODEL

While dental hygienists make decisions every day, ethical decision making can be more complex. Using the following decision-making steps may appear simplistic, but it can be extremely useful in solving ethical dilemmas. Similar to how keeping a food diary can help with nutritional counseling and counting calories, writing down the items in each of these steps can assist with ethical decision making.2

- Identify the problem

- Gather the facts (ask questions)

- List alternatives (pros and cons)

- Select a course of action

- Act on the decision

- Evaluate the action

When working through each step, other factors to consider are the professional code of ethics; advice from superiors, peers, and role models; and previous personal experience.

ETHICAL DILEMMAS

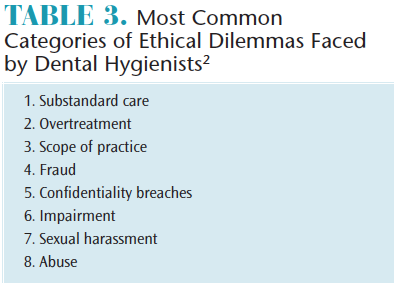

While a career in dental hygiene is incredibly fulfilling, it is not without challenges. Dental hygienists face ethical dilemmas that affect themselves and their patients, similar to other health professionals. Ethical issues in health care are common. Challenges such as balancing quality care and efficiency, improving access to care, and addressing end-of-life issues are frequently encountered in the medical profession.14 Additionally, sometimes patients’ personal or religious beliefs may clash with evidence-based treatment. Patients’ rights to make their own choices/decisions (autonomy) must be weighed against practitioners’ responsibilities to provide the best care (beneficence). According to Beemsterboer,2 eight categories of ethical dilemmas are most frequently encountered by dental hygienists (Table 3).

The following scenarios involve substandard care and scope of practice. They demonstrate how clinicians can work through the six decision-making steps.

Scenario #1. A new patient is referred to the dental office by a long-standing patient. The new patient presents with generalized 4 mm to 5 mm probing depths, classified as moderate chronic adult periodontitis, which has been treated in the past. The patient reports he had a traumatic experience with the previous dentist and periodontist. He states he will comply with treatment but will refuse any periodontal surgery or future supportive periodontal therapy beyond his 4-month periodontal maintenance visits. The patient has type II diabetes and high blood pressure, which are both controlled with medications. After several years of periodontal maintenance appointments, the dental hygienist notes that probing depths have increased approximately 1 mm to 2 mm over the past two visits to three visits, but knows the patient is adamant about not receiving additional periodontal treatment. She also understands that the patient is trying to comply and is concerned he would be upset if she mentioned that his periodontal status was declining. The decision making steps are as follows:

- Identify the problem. The patient’s periodontal status is declining. The dental hygienist is torn between informing the patient of his periodontal status and potentially upsetting him by recommending more advanced periodontal therapy.

- Gather the facts. Complete periodontal and radiographic assessments and ask the patient about any changes in medications or control of systemic conditions that may affect his periodontal status. Review diabetic history and treatment with physician.

- List alternatives. Inform the patient of his change in periodontal status or complete the maintenance appointment without discussing the periodontal findings.

- Select the course of action. The dental hygienist chooses to inform the patient as she realizes several core values are evident. The first core value involves autonomy, in which patients have the right to full disclosure of relevant information so they can make informed choices about their care.1 A second core value related to this scenario is beneficence, in which dental hygienists are obligated to promote the well-being of individuals by engaging in health promotion/disease prevention activities.1 A third core value relates to veracity in which dental hygienists are obligated to tell the truth in patient/practitioner relationships.1

- Act on the decision. The dental hygienist discusses the findings with the patient and informs him that she will present these findings to the dentist, so everyone can be involved in the decision about whether to proceed with further periodontal treatment.

- Evaluate the action. Whatever the outcome, the dental hygienist reflected on the core values used in the decision-making steps and knows she “did the right thing.”

Following is a different type of ethical dilemma regarding employment issues.

Scenario #2. A dental hygienist is hired at a private practice immediately upon graduation from his dental hygiene program. After a few weeks of working in the office, the dental hygienist observes that the dentist leaves early upon completion of her own scheduled appointments and after finishing all hygiene exams. The dental hygienist is familiar with the laws in his state and knows he needs to work 1 year before becoming eligible to practice under general supervision. The dental hygienist discusses his concern with the dentist but she continues to leave the practice early, even when the dental hygienist has patients to complete.

The decision-making steps are as follows:

- Identify the problem. The dentist is not in the office while the newly graduated dental hygienist is still treating patients, which is in violation of the state’s dental practice act.

- Gather the facts. In this particular state, dental hygienists are required to have at least 1 year of experience before becoming eligible to treat patients under general supervision. The dental hygienist could face action by the dental board if the situation came to its attention.

- List alternatives. The dental hygienist could speak to the dentist again, emphasizing the seriousness of the issue and try to resolve the situation. He could continue to work in the office and treat patients even when the dentist leaves. He could discontinue the treatment of his patient when he knows the dentist has left the office. He could terminate his employment at the office, although this is not an ideal option because he has a significant student loan debt and he truly enjoys working at the dental practice.

- Select the course of action. The dental hygienist chooses to speak to the dentist one more time, being more adamant about the legalities of the situation and how he does not want to jeopardize his dental hygiene license. In addition, he emphasizes if an emergency were to occur or the patient had more questions for the dentist, the dentist needed to be available. He does not want to jeopardize the patient’s care in any manner (nonmaleficence). In addition, patients assume the dental hygienist is practicing legally and within his scope of practice (trust). The behavior of the dentist does not change.

- Act on the decision. The dental hygienist decides to look for other employment opportunities and leaves the original office when a new position is secured.

- Evaluate the action. The dental hygienist knows he “did the right thing,” even though he truly enjoyed other aspects of the office. He realized it was not worth jeopardizing his license and learned to discuss general supervision rules with all potential employers before accepting a new position.

CONCLUSION

Many factors should be considered when making ethical decisions. It is important to work through ethical scenarios throughout dental hygiene education and to use ethical decision-making steps in order to adequately solve dilemmas when they arise. With changes in dental hygiene curricula and added questions on the NBDHE, dental hygiene graduates should have sufficient training in ethics to handle dilemmas they may encounter in their professional careers. Dental hygienists are charged with continuing to practice with the highest standards of care, remembering the oath taken prior to becoming a licensed professional, and always “doing the right thing.”

References

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Bylaws and Code of Ethics. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7611_Bylaws_and_Code_of_Ethics.pdf. Updated 2016. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- Beemsterboer P. Ethics and Law in Dental Hygiene. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2017.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. 100 Years of Dental Hygiene. Available at: tiki-toki.com/ timeline/entry/55646/100-Years-of-Dental-Hygiene/ #vars!panel=679914!. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- Furnari W. The dental hygiene oath or pledge. Access. July 2012:10.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs. Available at: ada.org/ ~/media/CODA/Files/dh.ashx. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- Kacerik MG, Prajer RG, Conrad C. Ethics instruction in the dental hygiene curriculum. J Dent Hyg. 2006;80:9–9.

- Jong A, Heine CS. The teaching of ethics in the dental hygiene curriculum. J Dent Educ. 1982;46:699–702.

- Gaston MA, Brown DM, Waring MB. Survey of ethical issues in dental hygiene. J Dent Hyg. 1990;64:217–224.

- Duley SI, Fitzpatrick PG, Zornosa X, Lambert CA, Mitchell A. Dental hygiene students’ attitudes toward ethical dilemmas in practice. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:345–357.

- Blue CM. Cultivating professional responsibility in a dental hygiene curriculum. J Dent Educ. 2013;77:1042–1051.

- Joint Commission on National Dental Examinations. National Board Dental Hygiene Examination 2017 Guide. Available at: ada.org/ ~/media/JCNDE/pdfs/nbdhe_examinee_guide.pdf?la=en. Accessed April 18, 2017.

- Berk NW. Teaching ethics in dental schools: Trends, techniques, and targets. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:744–750.

- Larson J. Five top ethical issues in healthcare. Available at: amnhealthcare.com/latest-healthcare-news/five-top-ethical-issues-healthcare/. Accessed April 18, 2017.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2017;15(5):37-40.