Digital Dental Imaging

Incorporating the intraoral camera into day-to-day practice can improve the efficacy and efficiency of assessment, patient education, treatment planning, and documentation.

This course was published in the January 2013 issue and expires January 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the evolution of the intraoral camera.

- Identify the benefits of using intraoral cameras during dental hygiene treatment.

- Detail the role of intraoral cameras in caries detection and oral cancer detection.

- List the necessary parameters for implementation of the intraoral camera into dental hygiene practice.

The first intraoral camera was developed in the 1980s. Fuji Optical Systems acquired the first registered trademark on July 7, 1987, with the DentaCam. Intraoral cameras were initially housed in large cabinets that held the unit, monitor, printer, storage device, and large wired camera. They were extremely bulky and the wired handles made manipulating them intraorally difficult. Modern intraoral cameras are compact and the image-capture buttons are at the clinician’s fingertips, enabling the quick and simple display and storage of images (Figure 1). Many options are also wireless.

EVOLUTION OF THE DEVICE

The initial idea for the intraoral camera was derived from endoscopes, which are tiny cameras used to examine the interior of an organ or cavity within the body.2 Endoscopes have been used for many years in medicine, and are frequently utilized in gastroenterology, respiratory medicine, gynecology and obstetrics, and orthopedics. The dental endoscope was introduced in the late 1990s. Used in periodontal diagnosis and therapy, the dental endoscope provides clinicians with direct, real-time visualization and magnification of the subgingival tooth root surface, aiding in the identification of deposits on the tooth surface.3

Intraoral cameras are based on the same idea as endoscopes, using a small visualization device to provide a better view of the oral cavity. The intraoral wand camera projects magnified digital images from a patient’s mouth onto a screen, usually a laptop computer, desktop computer, or other type of display, such as a high definition television or liquid crystal display-equipped device. Images are stored and saved using a digital imaging software system.

These images can be saved and recalled at future appointments to compare or enhance changes to intraoral tissues or structures. Digital imaging software typically provides additional options, such as the ability to exchange information and image enhancement.4 A digital single-lens-reflex (SLR) camera with a macro zoom lens and ring or ring/point combination flash can also be used in intraoral digital imaging. Once the images are taken with a digital SLR camera, they are stored and saved the same way as those taken by an intraoral wand camera.

APPLICATIONS FOR DENTAL HYGIENE AND DENTISTRY

Digital dental imaging has become an integral part of day-to-day practice in many dental offices5 and is most frequently used to document patient data.6,7 Documented images can be used to inform a patient’s family members, as well as provide records for insurance companies, archives, and to support a “wait-and-watch” approach. Patient portraits can be used to refresh staff members on the names of patients, so each person feels like a valued client in the dental practice. Providing patients with prints of their images is beneficial because they can then take them home to review. They can make communication with a referring specialist, such as a periodontist or oral surgeon, much easier.8

Intraoral cameras are very effective tools in patient education. By viewing images on the screen all together, the dental hygienist, dentist, and patient can “co-diagnose.”8 The magnification allows the patient to see intricate details of specific conditions that would not otherwise be visible or easily understood. Dental patients usually enter a dental office with varied levels of understanding about their oral conditions and their need for treatment.8 Showing the present condition of the teeth (decay, incipient lesions, fractured amalgams, composites, oral and mucosal lesions, calculus, staining) is vital for treatment acceptance. A great tool to increase motivation in self-care, patients can be shown the status of their current regimens, particularly if they are subpar. For example, patients can view for themselves the results of their poor oral hygiene, including calculus, stain, and caries (Figure 2 to Figure 6). The images are also useful in illustrating the possibilities of cosmetic dentistry, such as whitening, as well as esthetic surgical procedures like gingival reduction.

Assessment and treatment planning are also greatly supported through digital dental imaging. Explaining different treatment options through the viewing of digital images is helpful. For instance, if a patient’s decay is extensive, requiring a crown, the camera can be used to show the problem to the patient, supporting a trusting relationship between patient and provider and improving case acceptance.

RISK ASSESSMENT

Intraoral cameras and digital dental imaging can improve early detection of oral health problems, such as dental caries and oral cancer. Because traditional caries detection methods are limited in their ability to identify lesions until they have progressed through the enamel,9 the addition of caries detection technologies to digital dental imaging can help find lesions prior to cavitation. Intraoral cameras/caries detection devices use light-induced fluorescence to identify changes in the visual properties of enamel.10

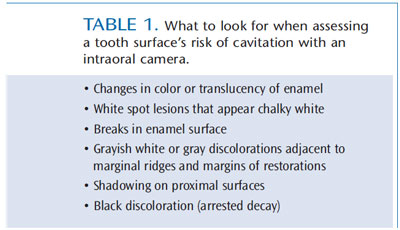

Risk assessment of a tooth surface for demineralization can also be conducted with a traditional intraoral camera. Table 1 provides a list of what to look for during this type of examination. Research indicates that compared to unaided vision, the use of an intraoral camera as an adjunct significantly increases the number of occlusal lesions detected.11 Another study found that intraoral cameras improved treatment planning for restorative care on posterior teeth.12

Intraoral cameras are also useful in oral cancer detection. By providing documentation of the oral cavity, clinicians can use these images for reference should any suspicious lesions develop. Intraoral camera images can be used to monitor oral lesions for changes in size, color and consistency (Figure 7 to Figure 9).

TELEDENTISTRY

Digital dental imaging is also used in teledentistry, which is helping dental professionals provide care in underserved areas. The dentist performs the exam from an electronic submission of images via email. He or she then examines the images to diagnose decay or any other dental issues. Teledentistry is currently used by the United States Department of Defense in its Total Dental Access program.13 The project provides military personnel with quality dental care while they are stationed in remote areas through the use of digital dental imaging.

IMPLEMENTATION

The intraoral camera wand presents a unique challenge from an infection control standpoint. It is usually covered with a plastic disposable sleeve to protect it from contamination. The use of disposable sleeves reduces or eliminates the need for sterilization, however, decontamination and intermediate level disinfection are required if the wand makes contact with saliva or mucosa.8

Tosupport the incorporation of the intraoral camera into dental practice, Bengal created standardization guidelines for the clinical camera and related equipment, including image formatting and lighting.7 He suggests that new technology should cause minimal disruption to daily work routines, avoid increasing the time needed to complete an appointment, and be easily mastered by clinicians.11 The guidelines suggest that clinicians adhere to the following recommendations.

Choose an intraoral camera that provides a wide observation field, so several teeth can be seen in a quadrant at one time. It should also offer an accurate, clear view for patients. The camera should be small in size but provide a high resolution (40 times to 60 times the original size).7 The camera needs to produce still photos as well as accurate color reproduction. The ability to rotate images is also key to the device’s usability. In order to ensure quality photos, the camera should have automatic light regulation. It should also be simple to use, require no warmup time, and be activated with clear controls. Finally, clinicians must be able to print out all captured images for use in patient education and documentation.

SUMMARY

Intraoral cameras and digital dental imaging are valuable tools for assessment, education, treatment planning, and documentation. The images produced by intraoral cameras encourage discussion between patients and the dental team, fostering joint decision-making. Experience in using intraoral cameras can also provide career benefits. Dental hygienists well versed in intraoral camera use and image management are highly valued because these skills may help increase patient case acceptance. With benefits for both patients and providers, intraoral cameras should become part of the dental hygienist’s practice armamentarium.

REFERENCES

- Tay KI, Wu JM, Yew MS, Thomson WM. The use of newer technologies by New Zealand dentists.N Z Dent J. 2008;104:104–108.

- Peithman K. Portable dental camera and system. United States Patent Number 5,487,661.January 30,1996.

- Stambaugh RV. Endoscopic visualization of the submarginal gingival dental sulcus and tooth rootsurfaces. J Periodontol. 2002;73:374–382.

- Versteeg CH, Sanderink GC, van der Stelt PF. Efficacy of digital intra-oral radiography in clinicaldentistry. J Dent. 1997;25:215–225.

- Chossegros C, Guyot L, Mantout B, Cheynet F, Olivi P, Blanc JL. Medical and dental digitalphotography. Choosing a cheap and user-friendly camera. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofaci. 2010;111:79–83.

- Barut C, Ertilav H. Guidelines for standard photography in gross clinical anatomy. Anat Sci Educ.2011;4:348–356.

- Bengel W. Standardization in dental photography. Intl Dent J. 1985;35:210–217.

- Obrochta JC. Efficient and effective use of the intraoral camera. Available at: media. dentalcare.com/ media/en-US/ education/ ce367/ ce367.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2012.

- Barnes CM. Dental hygiene participation in managing incipient and hidden caries. Dent Clin NorthAm. 2006;49:795–813.

- Ferreira Zandoná AG, Analoui M, Beiswanger BB, et al. An in vitro comparison between laserfluorescence and visual examination for detection of demineralization in occlusal pits and fissures.Caries Res. 1998;32:210-218.

- Forgie AH, Pine CM, Pitts NB. The assessment of an intra-oral video camera as an aid to occlusalcaries detection. Int Dent J. 2003;53:3–6.

- Erten H, Uçtasli MB, Akarslan ZZ, Uzun O, Semiz M. Restorative treatment decision making withunaided visual examination, intraoral camera and operating microscope. Oper Dent. 2006;31:55–59.

- Rocca MA, Kudryk VL, Pajak JC, Morris T. The evolution of a teledentistry system within theDepartment of Defense. Proc AMIA Symp. 1999:921–924.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2013; 11(1): 48–51.