Determining the Cause

Samuel W. Oglesby, DDS, MA, shares his expertise on the relationship between dentin hypersensitivity and endodontic problems.

Q. Is there a relationship between endodontic pulpal problems and dentin hypersensitivity?

A. This is definitely a complex subject that not only dental hygienists worry about it, but dentists as well. All dentin hypersensitivity hinges on the relationship between the dentin and the pulp; it’s basically a pulpal response to stimulus. Determining between a hypersensitivity problem that can be treated with topical treatments versus one that needs endodontic treatment is difficult. Listening to the patient can make this decision easier. Dental professionals need to ask patients how bad the pain is and how long it lasts once it’s provoked. A prolonged or lingering pain after the stimulus is generally a sign of disease having spread into the pulp, thus endodontic treatment is probably needed.

If the patient says, “I’m sensitive when I drink something cold” the dental professional needs to follow up with “How long does the pain last?” If the patient says it is alleviated right away, then it’s most likely reversible pulpitis.

Q. If a patient experiences dentin hypersensitivity, does this mean he or she has reversible pulpitis?

A. Dentin hypersensitivity can lead to reversible pulpitis if the sensitivity does not linger for more than a few seconds after the stimulus is removed. If it lingers for more than 30 seconds after the stimulus is removed, then most likely irreversible pulpitis has occurred.

Reversible pulpitis is a condition where the pulp reacts more quickly or more sharply to the stimulus than regular pulp. If the pulp is inflamed, the diagnosis is most likely dentin hypersensitivity and won’t need endodontic treatment.

Another factor that helps determine between dentin hypersensitivity and a more serious problem is the patient’s history of spontaneous or unprovoked pain. Spontaneous pain is often a sign that a pulpal problem exists that will require endodontic treatment.

Q. Do radiographs provide any hints on the etiology of dentin hypersensitivity?

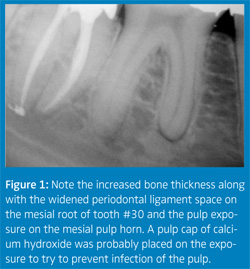

A. Generally with dentin hypersensitivity, radiographic changes do not appear in the bone. A shallow carious lesion may be visible but there won’t be any widening of the periodontal ligament or thickening of the bone around the apex (see Figure 1). If these types of changes are present, then the hypersensitivity has probably progressed into an irreversible pulpitis situation that may need endodontic treatment. Only in severe cases of cervical erosion is it possible to see loss of tooth density at the cervical zone.

Q. Can a tooth that’s been hypersensitive for a period of time and remains untreated result in an endodontic problem?

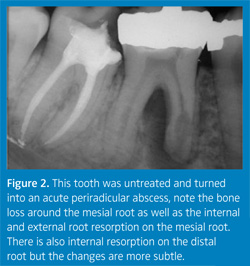

A. It can progress to an endodontic problem or it may just remain as dentin hypersensitivity indefinitely (Figure 2). I have on rare occasions performed endodontic treatment on a tooth with dentin hypersensitivity as a way of getting rid of the sensitivity. Sometimes the patient will say, “I’d rather have a root canal than have the sensitive tooth.” We know that the root canal will get rid of the sensitivity. However, long-standing treatments exist for sensitivity, like fluoride varnish, oxalates, and potassium nitrate, along with newer formulations such as amorphous calcium phosphate and arginine bicarbonate, which require more research, that can be tried first.

Often topical treatments will either alleviate or minimize dentin hypersensitivity. When it becomes intolerable or develops into a pulpal pathosis (prolonged, lingering hypersensitivity after removal of stimulus), then endodontic treatment is advised.

Q. What are some subtle, early warning signs that dental professionals can look for when trying to determine if a dentin sensitivity problem needs to be referred to an endodontist?

A. Number one on my list is listening to the patient’s story. This provides the most information. The second most effective strategy is pulp testing and third is using radiographs.

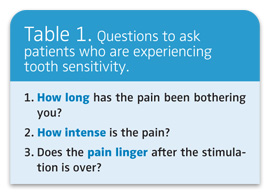

See Table 1 for a list of questions to pose to patients. Too often we are in a hurry to get the treatment done and forget that we need to listen to the patient.

When conservative measures are ineffective, the patient can no longer tolerate the hypersensitivity, or pulp vitality testing indicates pulpal pathosis, then referral to an endodontist is appropriate.

Q. Does temperature sensitivity provide any clues?

A. It does if pulp testing is performed. Pulp testing is also effective and easy. The cold test entails placing a piece of ice on the facial surface of a tooth. A normal control tooth should be done first to determine what a normal response is for the patient, then the suspected sensitive tooth should be tried. If a tooth has a crown, ice should be placed at the gingival margin. A patient can almost always tell the difference between ice on a tooth and ice on the gingiva. To diagnose dentin hypersensitivity on a tooth, a quicker/more painful response will result as compared with the control. In some patients, everything is sensitive and it may be difficult to differentiate the normal from abnormal sensitivity.

Heat testing can be done by holding a piece of gutta-percha with cotton pliers, heating it with a Bunsen burner, and placing it on the facial of the control tooth and then reheating and placing the gutta-percha on the suspect tooth. As long as the gutta-percha is not on fire and can be held by the cotton pliers, it is not too hot.

In my experience, heat sensitivity is more of an indication that a pulpal problem exists than cold. Again, spontaneous pain, lingering pain, and severe pain are more accurate indicators of needing endodontic treatment. If the patient isn’t able to eat due to the sensitivity even without spontaneous pain or lingering pain, a treatment plan is necessary, not advice to “keep an eye on it.”

Q. What treatments are available besides over-the-counter options and before endodontic treatment is initiated?

A. One treatment modality that is backed by scientific studies is iontophoresis,1,2 which is basically running a mild electric current through a tooth through a solution of sodium fluoride. This actually moves the fluoride ions into the dentin, into the tooth structure, and helps desensitize the tooth. An iontophoresis device looks like a small pulp tester and is basically a small battery device used to run an electric current. It costs a few hundred dollars. Physicians use it to deliver medications through the skin. However, iontophoresis is not readily available in the dental setting.

Other options include prescription strength fluorides, potassium nitrate applied with a home tray, dentin bonders, chemical desensitizers, and surface sealants.

REFERENCES

- Gangarosa LP, Park NH. Practical considerations in iontophoresis of fluoride for desensitizing dentin. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;39:173-178.

- Singal P, Gupta R, Pandit N. 2% sodium fluoride-iontophoresis compared to a commercially available desensitizing agent. J Periodontol. 2005;76:351-357.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2007;5(4): 22, 24.