SANKALPMAYA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

SANKALPMAYA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

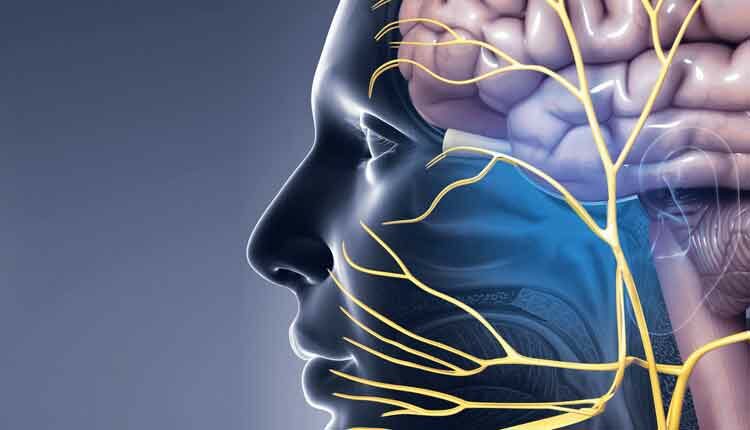

Detecting Trigeminal Neuralgia in the Dental Setting

Dental hygienists should be able to recognize the symptoms of this neuropathic pain condition and adapt the provision of care to avoid triggering pain in this patient population.

This course was published in the May 2021 issue and expires May 2024. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define trigeminal neuralgia (TN) and identify its etiology.

- Note the methods of diagnosis for TN.

- List treatment options for trigeminal neuralgia.

- Discuss responsibilities of the dental hygienist related to patients with trigeminal neuralgia.

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN), or tic douloureux, is a severe, shock-like neuropathic pain resulting in sudden—usually unilateral—short, stabbing, recurrent pain in the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve, often set off by light stimuli, such as touch or movement, in a trigger zone.1,2 It typically presents with piercing pain along the nerve path, which may last from seconds up to several minutes, without associated sensory loss. Assessment may reveal trigger points that exacerbate the paroxysm or sudden attacks. TN may develop without apparent cause or be the result of another diagnosed disorder.3–5

TN affects 12 people per 100,000 each year, with women at greater risk than men. The disorder typically occurs between ages 50 and 70.4 TN’s risk factors and etiology are largely unknown, but arterial or venous pressure on the fifth cranial nerve may be a causative factor. Some patients with TN have multiple sclerosis (MS) or a tumor that causes compression near the associated trigeminal nerve.6

Pathophysiology

TN is associated with an unknown origin from the fifth cranial or trigeminal nerve, which may cause sensation of the maxillary and mandibular facial regions.7 Although the origin of the pain is at the trigeminal root, the pain is more often located on the right side in the second or third trigeminal division, both intraorally and extraorally.8–10 Typically, TN results from deterioration of the protective sheath around the trigeminal nerve or vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve root; this may be due to an abnormal loop of the cerebellar artery. When the artery is compressed constantly, the associated nerve may begin to atrophy and the myelin sheath is destroyed.11 Degenerative changes of the sensory ganglion, which generate the altered impulse transmission, may also cause TN.4 Individuals with TN describe the pain as an electric shock that radiates down the path of the trigeminal nerve around the lower jaw and cheek area.7

Because the intensity of the pain brought on by TN produces psychosocial dysfunction, such as anxiety and depression, the patient’s quality of life is significantly impaired, requiring a prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.5,12 Accurate diagnosis depends on a patient’s description of pathognomonic pain, and begins with careful assessment of the medical history and physical examination, identifying precipitating factors. No specific laboratory studies are indicated, although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or magnetic resonance angiography may be used.4

Classifications

The American Academy of Neurology developed a classification and diagnostic grading system that classifies TN in three etiology categories: idiopathic, classic, and secondary. Idiopathic and classical TN are subdivided by whether the pain is paroxysmal or continuous. Idiopathic TN occurs without apparent cause, while classical is caused by vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve root.10,12 Classic TN pain starts suddenly as episodic paroxysmal attacks that may last seconds to minutes. The pain attacks occur daily and may be described as electric lancing, burning, or tingling sensations projected to a cutaneous area. The pain is often associated with triggers in small sensory zones such as touching or washing the face, speaking, eating, drinking, chewing, wind blowing on the face, or brushing the teeth.13–15 The most common trigger zones are the nasolabial area, upper and lower lip, chin, cheek, and alveolar gingiva.10 Most patients experience more than one trigger zone and, unfortunately, the location of the pain is not always concordant with the site of a sensory trigger.

Secondary TN typically evolves from a major neurologic disease, such as MS, tumors, or cysts.16 Benign tumors cause compression leading to trigeminal pain. Secondary TN pain does not resemble classic TN pain, as patients will experience atypical facial pain most of the time. This can be displayed as aching, throbbing, burning, or continuous pain. Young patients diagnosed with secondary TN should also be evaluated for underlying MS, as this condition often goes undiagnosed.17

Healthcare professionals must differentiate between classic TN and atypical face pain. The differential diagnosis of atypical facial pain includes post-herpetic neuralgia, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, dental abnormalities, temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD), and benign cephalgias, such as cluster headaches.15 Atypical face pain, commonly referred to as persistent idiopathic facial pain, is of unknown origin felt in the face. With persistent idiopathic face pain, individuals experience deep facial pain with indistinct borders.18 Additionally, healthcare professionals must rule out primary headaches, toothache, and TMD.5 Correct diagnosis is essential to ensure the most appropriate treatment.

Diagnosis and Referral

When patients experience pain evoked by perioral triggers associated with TN, their first visit may be to their dental home. A comprehensive intra- and extraoral examination paying special attention to the trigeminal and cranial nerves should be performed to rule out any other pathologies.17 The sensory examination should include a careful search for intraoral trigger zones and areas of sensory loss. Comprehensive and periodic appointments should consist of an intra- and extraoral evaluation completed by the dental hygienist, including visual inspection of the lips, mucosal surfaces, and oral cavity.19 The lips, cheeks, and floor of the mouth should be palpated, and salivary gland function should be examined to identify salivary flow. The head and neck exam involves overall appraisal of the head, neck, face, and skin. Lymph nodes should be palpated and the temporomandibular joint should be evaluated to assess the range of motion.19 If the dental hygienist suspects TN, a referral should be made to the proper specialist. Often, a general practitioner is the first referral made by the dentist, but a neurologist may be the most prepared to diagnose the condition.

A detailed medical history and physical exam are key to diagnosing TN.13,15 Upon observing the patient while he or she is completely still, the physician may notice a spontaneous spasm, such as a blink or a small mouth movement. The patient may also report neuropathic pain, which may make it difficult for the patient to convey his or her pain experience. While TN has a typical clinical picture, diagnosis is often missed or delayed in clinical practice, by either a dentist or general practitioner. More than one-third of patients presenting at a dental office with undiagnosed TN will undergo unnecessary dental procedures or delays in treatment.5,8,14,20

In the dental setting, there are no specific ways to diagnose TN; however, radiographs of the teeth and temporomandibular joint can help eliminate other causes of pain. A detailed intraoral examination of the dentition, oral cavity, oropharynx, salivary glands, and associated oral structures should be performed to rule out any other pathologies. Imaging, such as MRI, has the highest sensitivity and specificity of all imaging modalities. It can demonstrate neurovascular contact and may demonstrate deformation of the trigeminal nerve caused from sclerosis or masses.15,17,21

Treatment

Treatment options for TN are aimed at minimizing and eradicating the pain attacks and include medical management, pharmacologic treatment, microvascular decompression, radiosurgery, and percutaneous trigeminal ganglion techniques.22,23 Additionally, some patients report pain control is assisted by complementary and alternative medicine, such as nutritional therapy, biofeedback, acupuncture, and botulinum toxin-A injections.4,24

The pharmacologic approach to TN treatment has not changed much in the past decade. TN responds to certain antiepileptic medications but not to traditional analgesics. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclics, narcotics, analgesics, and even opioids achieve very little in the way of pain relief.7,25 Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, both anticonvulsants, are the first choice for long-term treatment, although they can cause negative side effects including cognitive impairment, memory loss, and bone marrow suppression.10,12,25 Gabapentin, an anticonvulsant used to treat neuropathy, has emerged as a possible treatment; however, its efficacy is only half of carbamazepine’s. But it exerts fewer adverse effects and drug interactions, which is advantageous when treating older adults.

In rare cases, neuralgia will escalate to the point of extreme crisis. If patients are unable to eat, drink, or speak due to attacks, pain control must be achieved through a lidocaine transcutaneous patch, intraoral viscous gel, or surgical treatment.25 The evidence for these options is limited and further research is warranted.26

Surgical treatment is typically reserved for patients whose pain is debilitating and cannot be controlled following trial of at least three medications. Patients whose pain is controlled by medication will often request surgical treatment because they fear the pain may return or progress. Studies indicate some patients would have opted for surgery sooner if given the opportunity.10,25

Microvascular decompression relieves pressure from the trigeminal nerve by alleviating constricting blood vessels.10,25 Following this procedure, patients often experience immediate pain relief. Negative side effects include the risk of injury to other facial nerves.18

Percutaneous thermocoagulation of the trigeminal ganglion is the most common surgical procedure to treat TN.25 Boasting an efficacy rate of up to 93%, this procedure may be repeated if needed.18 Unfortunately, it is associated with abnormal facial sensations, reported as itching or burning.18

Optimal management of TN can only be achieved by determining an accurate and complete diagnosis and identifying all factors associated with the underlying pathology on a case-specific basis.14

Implications for the Dental Hygienist

Patients with neuropathic orofacial pain require dental treatment, either as routine maintenance or emergency visits. Because the pain can be so severe, patients may avoid dental treatment, leading to increased incidence of caries or periodontal diseases. While it is not comfortable for the patient to receive routine treatment, maintenance may reduce the need for invasive dental treatment in the future. When invasive hygiene procedures are required, such as gross debridement or scaling and root planing, dental hygienists should begin with the least invasive approach.27

Patients may present with heavy plaque biofilm and calculus, decay, failed restorations, periodontal diseases, candidiasis, or angular cheilitis.28 If the patient has facial weakness or unilateral numbness, plaque and calculus will be more abundant on that side due to less cleansing ability and masticatory efficiency. A decrease in salivary flow can also contribute to a higher incidence of caries, so routine application of fluoride varnish and daily fluoride exposure are necessary.26 Dental hygienists should make every effort to provide maximum comfort during and after the appointment. With pain fluctuating during the day for some patients, appointments should be scheduled during the time of lowest pain or during periods of remission.30 When the patient is taking medications to treat the condition, appointments should be made at their peak level of effectiveness.

Careful consideration should be used to not exacerbate pain when administering anesthesia. Prior to administering anesthetic, dental hygienists should thoroughly review the patient’s health history and medication regimen to gain a detailed understanding of drug uses and contraindications. To minimize pain, oral health professionals should take care in delivering the anesthetic to avoid tissue trauma. Administering local anesthesia after the procedure is complete to delay post-operative discomfort should also be considered.27

To minimize stimulation, oral health professionals can advise patients on adaptations to oral hygiene regimens. An extra-soft manual or power toothbrush should be recommended. Patients may exert better control with a power toothbrush and can avoid rapid movement common with a manual brush. During a severe episode, an alternative to brushing could include using a soft foam soaked in chlorhexidine.27 Various interdental aids can be used based on the patient’s preference for texture including soft picks, tufted floss, or rubber tip stimulators. An antiseptic, or alcohol-free mouthrinse containing fluoride should be used daily to reduce bacteria associated with caries and gingivitis. If the patient is at high or extreme caries risk, fluoride can also be delivered in custom trays on a daily basis.

Patients may be reluctant to undergo any dental procedure that involves manipulation in or around their mouths. With a knowledge of trigger zones and how TN manifests, clinicians can better treat the patient to avoid unnecessary discomfort during dental procedures. With early recognition and appropriate referral, possible complications can be avoided.

Conclusion

In order to promote positive patient outcomes, dental hygienists should be able to recognize symptoms of TN. Once symptoms are recognized, the dental hygienist should alert the dentist of the presence of these symptoms and initiate appropriate medical referrals.

References

- Rai A, Kumar A, Chandra A, Naikmasur V, Abraham L. Clinical profile of patients with trigeminal neuralgia visiting a dental hospital: A prospective study. Indian Journal of Pain. 2017;31(2):94.

- Zakrzewska JM, Wu J, Mon-Williams M, Phillips N, Pavitt SH. Evaluating the impact of trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 2017;158:1166–1174.

- Misulis K, Murray EL. Sensory abnormalities of the limbs, trunk, and face. In: Daroff RB, Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, eds. Bradley’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia Elsevier; 2016.

- Handel W. Primary care. In: Trigeminal Neuralgia. 6th ed. Philadelphia; Elsevier; 2021.

- Antonaci F, Arceri S, Rakusa M, et al. Pitfalls in recognition and management of trigeminal neuralgia. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:82.

- Smith J.Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Ferri F, ed. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2021.

- Woods L. Facial and ocular emergencies. In: Newberry L, ed. Sheehy’s Emergency Nursing. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2018.

- Cruccu G, Di Stefano G, Truini A. Trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:754–762.

- Di Stefano G, Maarbjerg S, Nurmikko T, Truini A, Cruccu G. Triggering trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia. 2017;38:1049–1056.

- Bendtsen L, Zakrzewska JM, Heinskou TB, et al. Advances in diagnosis, classification, pathophysiology, and management of trigeminal neuralgia. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:784–796.

- Hagler D, Harding M, Kwong J, Roberts, D, Reinisch C. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Lews SL, Hagler D, Bucher L, et al, eds. Clinical Companion to Lewis’s Medical-Surgical Nursing. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2020.

- Hwang JH, Ku J. Herbal medicine for the management of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20779.

- Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. BMJ. 2015;350:1238. .

- Spencer CJ, Neubert JK, Gremillion H, Zakrzewska JM, Ohrbach R. Toothache or trigeminal neuralgia: treatment dilemmas. J Pain. 2008;9:767–770.

- Tai AX, Nayar VV. Update on trigeminal neuralgia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21:42.

- Cruccu G, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 2016;87:220–228.

- Scrivani SJ, Mathews ES, Maciewicz RJ. Trigeminal neuralgia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:527–538.

- Garza I. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of face pain, dysaesthesias, anaesthesia and skin/soft tissue lesions. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:980–985.

- Gehrig JS. Patient Assessment Tutorials : A Step-by-Step Guide for the Dental Hygienist. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2018.

- Khan ZA, Siddiqui AA, Alam MK, Altamimi YS, Ammar Z. Multiple sclerosis diagnosed in patients presenting with trigeminal neuralgia at Oral Medicine Department, Khyber College of Dentistry, Peshawar. International Medical Journal. 2020:27(5):636–638.

- Ovallath S, Sreenivasan P, RaJ Sumal. Treatment options in trigeminal neuralgia an update. Electronic Journal of General Medicine. 2014;11:3.

- Kumar S, Rastogi S, Mahendra P, Bansal M, Chandra L. Pain in trigeminal neuralgia: neurophysiology and measurement: a comprehensive review. J Med Life. 2013:6:383-–388.

- ScienceDirect. Trigeminal Neuralgia. Available at: sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/trigeminal-neuralgia. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Wei J, Zhu X, Yang G, et al. The efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and peripheral neuropathic pain: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01409.

- Cheshire WP. Trigeminal neuralgia: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005;5:79–85.

- Kern KU, Schwickert-Nieswandt M, Maihöfner C, Gaul C. Topical ambroxol 20% for the treatment of classical trigeminal neuralgia – a new option? initial clinical case observations. Headache. 2019;59:418–429.

- Klasser GD, Gremillion HA, Epstein JB. Dental treatment for patients with neuropathic orofacial pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1006–1008.

- Dawidjan B. Idiopathic facial paralysis: a review and case study. J Dent Hyg. 2001:75:316–321.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2021;19(5):26-28,31.