Dealing With Dementia

A patient-centered approach will help dental professionals improve both oral and systemic health outcomes for patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

This course was published in the July 2015 issue and expires July 31, 2018. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Describe the oral implications of the medications used to treat Alzheimer’s disease.

- Explain the importance of collaboration between dental hygienists and caregivers in promoting the oral health of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease.

As AD progresses, so does the severity of cognitive and functioning skill impairment.2 This decline increases patients’ susceptibility to oral diseases due to their inhibited ability to perform adequate oral hygiene.2 Challenges often faced by patients with AD and/or dementia include amassing of food fragments, ill-fitted and unclean prostheses, tooth loss, and increased risk for caries and periodontal diseases. To improve oral health in this patient population, health promotion efforts must be innovative, collaborative, and interdisciplinary. Maintaining a patient-centered approach is an important component of improving the oral health in patients with AD and/or dementia. Individuals with AD who depend heavily on caregivers with low oral health literacy are at greatest risk, so caregivers need to be included in all patient education efforts.2

The prevalence of AD is increasing. Over the next 50 years, the number of individuals affected by AD is predicted to triple or possibly quadruple.3 As such, oral health professionals will most likely treat patients with AD or other type of cognitive disorder and should be prepared to meet the needs of this growing population.

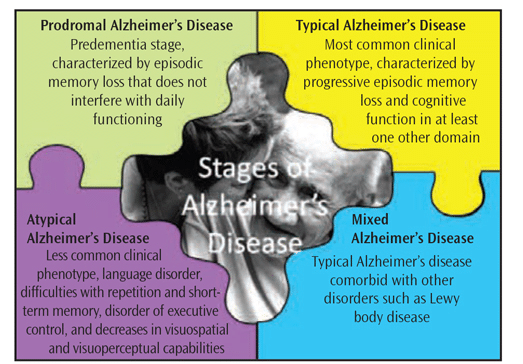

THE STAGES OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE PROGRESSION

AD is classified by stages of progression and clinical phenotype (Figure 1).4 Prodromal AD, also called the predementia stage, is characterized by episodic memory loss that does not interfere with daily functioning. The most common clinical phenotype of AD is termed typical AD. It results in progressive episodic memory loss and decreased cognitive function in at least one other domain. Atypical AD includes clinical syndromes such as progressive nonfluent aphasia (a disorder in which an individual loses the ability to communicate via speech, reading, writing, understanding); iogopenic aphasia (difficulty with repetition and short-term memory); frontal variant (a disorder of executive control); and posterior cortical atrophy (a decrease in visuospatial and visuoperceptual capabilities). Mixed AD refers to individuals with typical AD in addition to other disorders, such as Lewy body disease, another type of dementia.

The cause of AD is unknown, yet changes in the brain—such as neurofibrillary tangles and deposits of beta amyloid plaques—are often found during autopsies of individuals with AD.5 Conversely, these same biological markers of AD are found in the brain of older adults who died without presenting any clinical symptoms of the disease. Some researchers suggest inflammation may play a role in initiating AD.3

The progression of AD increases susceptibility to other medical complications such as urinary incontinence, balance problems that can lead to falls, delayed cognitive functioning, and dysphagia.6 Indeed, swallowing impairments may occur prior to clinical diagnoses.6 Patients often attribute their dysphagia symptoms to aging and fail to notify their health care professionals.7 A study of residents (n=107) residing in an urban independent-living community in the Southern United States found that 15% of participants responded yes when asked if they had experienced difficulty swallowing. This finding suggests that dental and medical professionals may want to consider including an assessment for dysphagia when evaluating the medical histories of older adults.

INFLAMMATION, ORAL HEALTH, AND COGNITIVE DECLINE

Chronic inflammation is of growing interest in the etiology of cognitive decline and AD.8 One theory suggests that long-term systemic infection may prime cells to act atypically, resulting in brain disease.3 Neuroinflammatory responses may be triggered by pathogens—both viral and bacterial.5 The oral microbiome can provide the source of chronic inflammation, especially when periodontitis is present.8

Oral microflora may spur inflammation, most commonly in the form of gingivitis. Ulcerated crevicular epithelium—typical of active periodontitis—may serve as a conduit for bacteria and other microorganisms to enter the bloodstream and potentially circulate to other locations. Periodontal pathogens may directly affect the brain via the circulatory system and/or the nervous system.3

Stewart et al8 investigated the relationship between periodontal diseases and cognitive decline. Researchers hypothesized that poor oral health status was associated with cognitive decline and that high levels of inflammatory markers would partially account for the relationship. A large cohort of individuals (n=3,075) age 70 to 79 participated in the 5-year study. In the second year of the study, the participants received dental examinations. Results indicated that gingival inflammation was a significant predictor of cognitive decline. A bidirectional relationship in which cognitive impairment leads to poor oral health may also exist.8,9

EFFECTS OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE PHARMACOTHERAPY

Medications can be effective in delaying cognitive impairment among patients with AD. Several prescription drugs are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat the disease’s symptoms.10

Cholinesterase inhibitors, such as galantamine, rivastigmine, and donepezil, are used to treat mild to moderate AD. The exact mechanisms in which cholinesterase inhibitors work are not fully understood, but they may inhibit the breakdown of acetylcholine, a chemical in the brain associated with memory and cognitive ability.10

Memantine, an N-methyl D-aspartate antagonist, is commonly used to treat moderate to severe AD.10 It works by regulating glutamate—a key neurotransmitter—and appears most useful in the later stages of AD. Tricyclic antidepressants, such as despiramine, notriptyline, and amitriptyline, are also used to treat AD. Antipsychotic, anxiolytic, and anticonvulsant medications may be prescribed to treat some of the behavioral symptoms of AD.11

As patients with AD often take multiple medications to treat their disease and other health problems, oral health professionals need to ensure that patients provide an updated, comprehensive medical history at each dental visit. This is imperative when administering anesthesia or prescribing antimicrobials and analgesics to patients with AD because these pharmacologics may interact with their current medication regimen.11

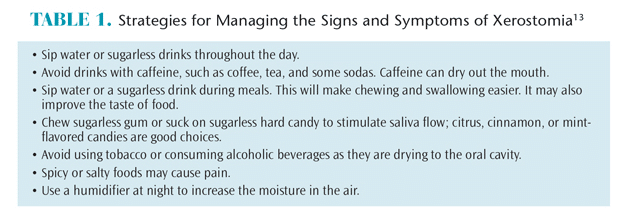

The multiple medications used to treat AD can impact oral health, such as increasing the risk of xerostomia or other problems that may affect the provision of dental care, including hypertension, nausea, coughing, dizziness, increased likelihood of syncope, and anxiety.11 Xerostomia is a common side effect in patients taking medications for AD.12 Oral health professionals can recommend over-the-counter (OTC) products to ease the symptoms of xerostomia such as salivary substitutes, oral lubricants, and sugarless gum with xylitol. Table 1 provides additional strategies for managing xerostomia.13

Blood pressure should be assessed as part of an overall evaluation of patients’ vital signs before dental treatment begins. Patients with AD who experience morning nausea may be more comfortable with dental appointments scheduled late in the day after their nausea has subsided. Ensuring that patients with AD have eaten prior to the appointment may reduce the risk of syncope and dizziness. Oral health professionals should also gradually raise the dental chair to the upright position following dental procedures to decrease the risk of syncope, dizziness, and falling.

THE ROLE OF ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Due to reduced cognitive abilities and difficulties with self-care, patients with AD may present with numerous oral health challenges and diseases.11 Maintaining comprehensive medical histories, consulting with patients’ primary health care providers, and educating caregivers about oral health ensure a patient-centered approach to care.

Treatment planning is influenced by the patient’s stage of AD. Oral health professionals need to determine the patient’s independence level and cognitive, mental, and physical status before providing care. Assessing these factors will determine if a patient is able to provide informed consent for dental treatment. If a patient cannot provide informed consent, it must be obtained from a responsible party before treatment can begin. A caregiver may also need to be present during dental appointments.12

The stage of AD also impacts the delivery of oral health instruction. All patient education should be shared with the patient’s caregiver and tailored to meet the individual’s needs. Patients in the early stages of dementia may only need to be reminded to brush their teeth. Tools to help patients perform effective self-care, such as electric toothbrushes or modified manual toothbrushes, may be helpful in this population (Figure 2 and Figure 3).14

During the later stages of dementia or AD, patients’ cognitive abilities decrease. This may result in reduced interest in oral care and/or inability to recall how to perform these tasks.12 At these stages, caregivers will need to provide oral hygiene care for patients. Additionally, individuals with AD may have difficulty expressing their dental concerns and explaining oral symptoms or pain. This leaves them unable to make decisions regarding dental treatment.12 The role of caregivers becomes more demanding as the disease progresses. Patients with AD need family members or caregivers to assume full responsibility for oral hygiene care in order to optimize oral health.

MEETING THE NEEDS OF A GROWING POPULATION

The number of older adults in the US has tripled over the past century and is projected to double again in the next 50 years.15,16 By 2030, nearly one in five Americans will be 65 or older.15 Research also shows that older adults are at greater risk of oral health problems than their younger counterparts.16 The preparation needed to meet the needs of this growing population will require innovation and collaboration both within and outside of the dental profession.

Although the etiology of AD and dementia is currently unknown, research is focusing on possible associations between oral health and cognitive decline. Preventive oral hygiene interventions are key to improving overall health and may help delay or prevent cognitive decline.17 Insufficient evidence and methodological deficiencies in prior research have precluded oral health—especially periodontal diseases—as a cause of cognitive decline.8 On the other hand, evidence supporting a causal relationship between oral health and dementia is inconclusive. Additional research is needed to answer these questions.

The abilities of caregivers to encourage, and, if necessary, to provide oral hygiene for patients with AD and to help them receive professional dental care significantly affects the oral health of this population. Dental hygienists can help caregivers understand the importance of maintaining oral health and provide instructions on how to provide effective oral hygiene care. More qualitative research is needed to examine strategies for ensuring caregiver compliance with oral hygiene regimens.

CONCLUSION

Increasing age is a significant risk factor for developing AD or other diseases that lead to dementia.18 Individuals with such cognitive problems will need support to maintain both their overall and oral health. As dementia progress, caregivers may need to assume full responsibility for a patient’s oral self-care as well as ensure patients receive timely and adequate professional care.

REFERENCES

- Darby ML, Walsh M. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2015.

- Ribeiro GR, Costa JL, Ambrosano GM, Garcia RC. Oral health of the elderly with Alzheimer’s disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:338–343.

- Tornwall RF, Chow AK. The association between periodontal disease and the systemic inflammatory conditions of obesity, arthritis, Alzheimer’s and renal diseases. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2012;46(2):115–123.

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Revising the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010:9:1118–1127.

- Licastro F, Carbone I, Raschi E, Porcellini E. The 21st century epidemic: infections as inductors of neuro-degeneration associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Immun Aging. 2014;11:44–62.

- Humbert I, McLaren D, Kosmatka K, et al. Early deficits in cortical control of swallowing in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:1185–1197.

- Chen P, Golub J, Hapner E, Johns M. Prevalence of perceived dysphagia and quality-of-life impairment in a geriatric population. Dysphagia. 2009;24:1–6.

- Stewart R, Weyant RJ, Garcia ME, et al. Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:177–184.

- Scannapieco FA. The oral microbiome: Its role in health and in oral and systemic infections. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 2013;35:163–169.

- National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s Disease Medications Fact Sheet. Available at: nia.nih.gov/ alzheimers/publication/alzheimers-diseasemedications- fact-sheet. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- Turner LN, Balasubramaniam R, Hersh EV, Stoopler ET. Drug therapy in Alzheimer’s disease: an update for the oral health care provider. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:467–476.

- Alzheimer’s Society. Dental Care and Dementia. Available at alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/ docu ments_ info.php?documentID=138. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Dry Mouth. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/oralhealth/ Topics/DryMouth/Documents/DryMouth.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Dental Care Every Day: A Caregiver’s Guide. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/oralhealth/Topics/ DevelopmentalDisabilities/DentalCareEveryDay.htm. Accessed June 15, 2015.

- Anderson LA, Goodman RA, Holtzman, D, Posner SF, Northridge ME. Aging in the United States: Opportunities and Challenges for Public Health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:393–395.

- Van der Putten GJ, De Visschere L, Van der Maarel-Wierink C, Vanobbergen J, Schols J. Hot topic in geriatric medicine: the importance of oral health in (frail) elderly people—a review. European Geriatric Medicine. 2013;4:339–344.

- Singh S, Shivhare UD, Sakarkar SN. Oral infections, a mirror of our overall health condition: An overview. International Journal of Pharmacy & Life Sciences. 2013;4(9):2976–2982.

- Vreugdenhil A. Aging-in-place: frontline experiences of intergenerational family carers of people with dementia. Health Sociology Review. 2014;23(1):43–52.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2015;13(7):37–40.