Cultivating Cultural Competency in the Dental Setting

With an increasingly diverse population, oral health professionals need to be able to communicate effectively with all types of patients.

This course was published in the January 2018 issue and expires January 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the growth in diversity in the United States.

- Explain the importance of cultural competency.

- Identify strategies for effective patient-provider communication.

- List oral health problems experienced by marginalized populations.

- Discuss the role of health literacy in oral health outcomes.

Dental hygienists practice in a variety of settings—private practice, public health, academia, and research to name a few. As essential members of the oral health care team, dental hygienists may provide treatment to people of various cultural backgrounds and belief systems. As such, they must strive to attain cultural competency by forming an active and trusting relationship with patients, which enables the provision of a more comprehensive and all-inclusive care.

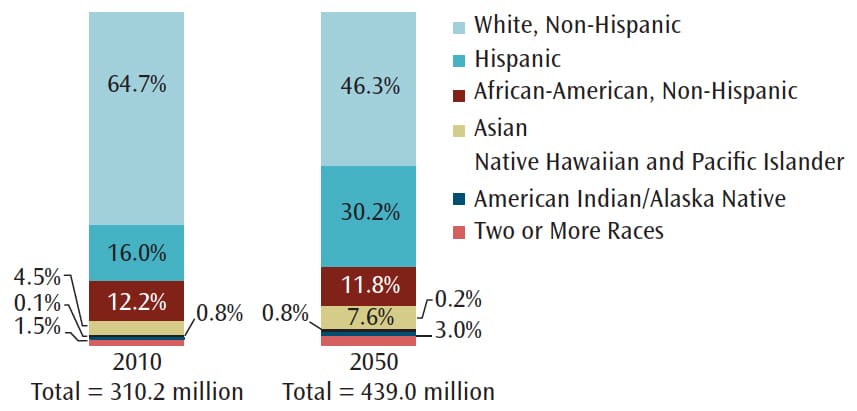

The United States has experienced a significant increase in diverse populations over the past several decades and these numbers will likely continue to rise. For example, Hispanics are the largest ethnic minority in the US. In 2014, Hispanics made up 17.4% (55.4 million) of the population and this percentage is expected to increase to 28.6% (119 million) by 2060.1 The exact numbers vary (Figure 1).2 The US lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ) population encompasses approximately 9 million people.3Roughly 4.1% of Americans identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender.3 As the diversity of the US increases, so must the knowledge of how to treat patients of various backgrounds, social realms, and belief systems. Oral health professionals need to be culturally competent to assess, diagnose, plan, and implement treatment according to individual patient needs.

Diversity involves a variety of factors, not just race and ethnicity. Sexual orientation, sex, age, socioeconomic status, religion, and health literacy are important to consider in the effort to provide culturally competent care. As the patient assessment and treatment plans are completed, all aspects of the individual must be considered. This may require asking personal questions. To be comfortable with diverse populations and delivering culturally competent care, oral health professionals must first learn to overcome the feeling of being uncomfortable. This can be accomplished through exposure to other cultures and learning to accept differences.

BUILDING CULTURAL COMPETENCY

Understanding diverse cultures is the first step in providing optimal patient care. Culture can be described as a set of beliefs, values, attitudes, and behaviors that are common within a group. These may be generational, learned patterns of beliefs and behaviors, or created in a current environment due to circumstances or actions of people within a group. Cultural competency may be depicted as a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enable that system, agency, or professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.4 A culturally competent health care provider is able to respond to groups with behaviors and attitudes that facilitate proficient treatment and communication. Another important aspect of cultural competency is cultural sensitivity, which involves making an effort to understand the culture(s) of patient populations. Oral health professionals are not expected to become fluent in multiple languages but rather to be proactive in using tools to enhance communication and understanding of the communities that comprise patient populations.

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Specific plans should be developed that are linguistically and culturally acceptable to patient needs. When health care providers fail to understand sociocultural differences, the communication and trust between providers and patients may suffer.5 This may lead to feelings of dissatisfaction, frustration, and anger. Furthermore, developing treatment plans and designing health history forms that are more inclusive of the population can enhance trust and help prevent miscommunication.

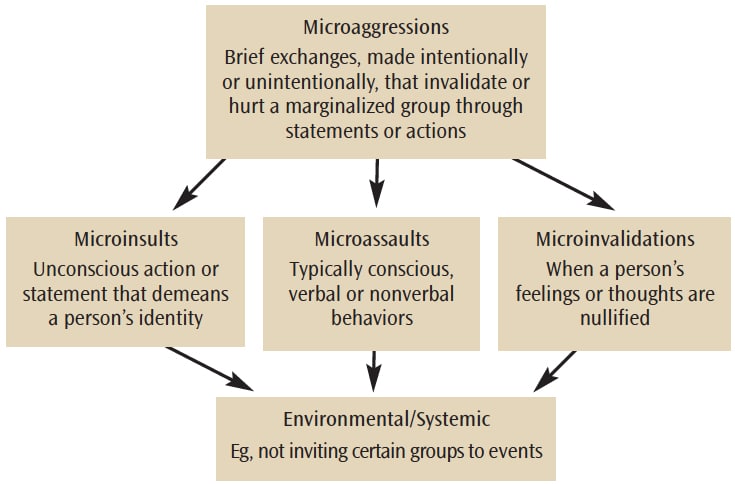

To provide culturally effective oral health care, a positive and dynamic relationship must be formed between patients and providers. This relationship requires individualized patient treatment—void of microaggressions—that is respectful and responsive to cultural needs. Microaggressions are brief exchanges—made intentionally or unintentionally—that invalidate or hurt a marginalized group through statements or actions.6 Microaggressions are brief daily indignities, which typically result in unintentional insults.

To provide culturally effective oral health care, a positive and dynamic relationship must be formed between patients and providers. This relationship requires individualized patient treatment—void of microaggressions—that is respectful and responsive to cultural needs. Microaggressions are brief exchanges—made intentionally or unintentionally—that invalidate or hurt a marginalized group through statements or actions.6 Microaggressions are brief daily indignities, which typically result in unintentional insults.

Microaggressions can be categorized as microassaults, microinsults, and microinvalidations (Figure 2). Microassaults are typically conscious, verbal, or nonverbal behaviors, whereas microinsults are unconscious actions or statements that demean a person’s identity. Much like a microinsult, a microinvalidation is when a person’s feelings or thoughts are nullified.7 Any of these can result in an environmental microaggression, which is when the insults, assaults, or invalidations manifest in an environmental or systemic level.8 For example, a microaggression would be to avoid inviting certain groups to events. An example of a spoken microinsult is “Male dentists are better than female dentists.” An example of a microassault is using derogatory slang to describe an individual’s race.8 Finally, an example of a microinvalidation is assuming a person of a different race or ethnicity does not understand what is being said and has less than average intelligence.

Microaggressions encompass several forms such as race, social class, sexual orientation, etc. In a study of the health-care experience of American Indians, 36% of the participants described undergoing some type of microaggression by a health care provider.9 Research suggests that microaggressions harmfully affect the mental health of marginalized social groups, causing depression, low self-esteem, and other mental health problems.7 Although the task of fairly treating patients is the goal of all team members, working with patients who differ in race, culture, socioeconomic status, literacy level, and sexual orientation may pose some challenges.

The ability to communicate with patients is one of the first steps to delivering culturally competent oral health care. Humans use many modes to communicate. Body language, including facial expressions, are integral to human communication. The ability of oral health professionals to effectively relay messages to patients is of the utmost importance. In some cases, patients may appear to have understood directions but may be too embarrassed to confirm their understanding. Patients with limited English proficiency and low health literacy will greatly benefit from alternative forms of communication, such as the teach-back method and the LEARN (listen, explain, acknowledge, recommend, negotiate) model. Both methods are based on clinician-to-patient communication skills, which enable the patient to partake in the learning and treatment planning process.

The ability to communicate with patients is one of the first steps to delivering culturally competent oral health care. Humans use many modes to communicate. Body language, including facial expressions, are integral to human communication. The ability of oral health professionals to effectively relay messages to patients is of the utmost importance. In some cases, patients may appear to have understood directions but may be too embarrassed to confirm their understanding. Patients with limited English proficiency and low health literacy will greatly benefit from alternative forms of communication, such as the teach-back method and the LEARN (listen, explain, acknowledge, recommend, negotiate) model. Both methods are based on clinician-to-patient communication skills, which enable the patient to partake in the learning and treatment planning process.

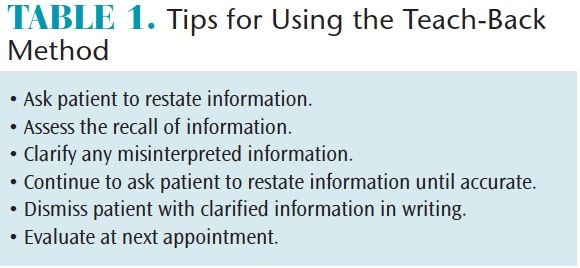

Involving the patient in the learning process via the teach-back method may increase the effectiveness of patient education (Table 1). This method is an effective way to check how well the patient understood the information provided.10 It involves asking patients to restate information that has been presented.11 Using the teach-back method enables oral health professionals to check for lapses in the recall of information.11 Any discrepancies in the restatement can then be assessed for comprehension problems, and the provider can explain any misinterpretations. If a patient has a low comprehension level due to language or literacy issues, then the information may need to be repeated and evaluated several times before true comprehension is attained. The teach-back method should be used on a regular basis when providing oral hygiene instructions but is even more critical when bridging the communication gap with patients who speak a different language or have low literacy. Results of a study on hospitalized patients with heart failure who were educated using the teach-back method found that 84% answered 75% of the questions correctly.11

The LEARN model assists clinicians in improving communication, increasing cultural awareness, and gaining more acceptance of treatment.12 The method focuses on listening with sympathy and understanding the patient’s perception of the problem, explaining perceptions, acknowledging and discussing the differences and similarities, recommending treatment, and negotiating agreement.13 For example, when a patient explains his or her perception of pain or treatment preferences, listening to these desires may assist in the acceptance of the treatment plan. Explaining procedures and providing options in terms that patients can understand may increase understanding and elicit compliance. When the patient acknowledges an understanding of treatment options, patient-to-provider trust increases. At this point, the oral health professional can recommend treatment and negotiate the treatment plan with the patient if necessary.

Good communication is important to establish a rapport and trust with the patient. Trust permits the patient to share medical histories more willingly. Patients often ask why oral health professionals ask so many nondental questions and one of those reasons is to determine any potential health disparities. A health disparity is a difference in health due to social, economic, or environmental disadvantages.14 As dental hygienists are often the first providers to review patients’ health histories, they need to understand what oral health disparities may exist.

ORAL HEALTH PROBLEMS

Pregnant women, children, and older adults often have significant oral health issues. These factors plus race/ethnicity, sociocultural backgrounds, type of employment, education, and insurance status all contribute to disparities. Among pregnant women, those enrolled in Medicaid were 24% to 53% less likely to seek oral health care than those with private insurance.15 Nearly 75% of caries in children ages 6 to 18 occurred in just 33% of the population, including African Americans, Mexican-Americans, American Indians/Alaskan Natives, and low-income groups.15 The rate for sealant application were 33% lower in African Americans and Mexican Americans than in whites.15 Among older adults, untreated caries was significantly higher in Hispanics (41%) and African-Americans (37%) than in whites (16%). The same is true for periodontal diseases, with 17% of older Hispanics affected, 24% of African-Americans, and 9% of whites.15 Evidence shows a significant disparity in oral health care among nonwhite and low-income populations.

IMPROVING HEALTH LITERACY

There appears to be a relationship between health disparities and low health literacy.14 Health literacy is the functional ability to read, understand, and act on health information.16 Populations with low income levels and low education levels are at increased risk for low health literacy and health disparities.

According to the US Department of Education and National Institute of Literacy, 14% of the US population cannot read and 21% read below a 5th grade level.17 A National Adult Literacy Study found that 21% to 31% of adults surveyed could not understand an appointment slip and 40% to 74% could not understand a general consent form.16

Adults with low health literacy may have difficulty reading insurance forms and completing health histories but they may be too embarrassed to ask for clarification. Low compliance with treatment and oral hygiene education could be an indication of low health literacy. Patients with low health literacy will likely not self-identify so oral health professionals must be able to recognize the signs, such as taking medications incorrectly or asking a family member to read forms aloud.16Literacy statistics indicate the factors that contribute to the highest level of low literacy is age (those older than 65), poverty, incarceration, immigration status, race, and lack of education (less than a high school diploma).16 Oral health professionals have an ethical obligation to assure that patients understand treatment plans, health histories, dental disease prognosis, and self-care instructions.

HEALTH DATA COLLECTION

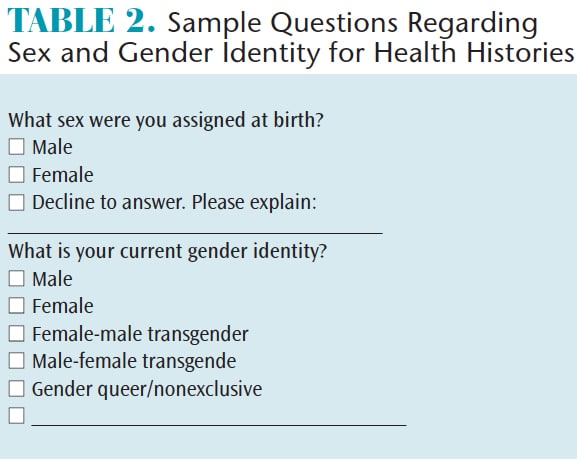

Health histories can be confusing or off-putting. Those used in the dental setting should be up to date on correct verbiage, inclusive, and easy to complete. According to the National Institutes of Health, appropriate racial categories are: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and white.18 Ethnicity can be described as Hispanic or Latino, which is an individual with cultural origins from Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Central or South America, or any other Spanish-speaking culture.18 Asking patients about race and ethnicity is more comfortable for most people than asking about sexual orientation. Health histories need to list (for insurance and billing reasons) the patient’s given birth name, but patients should also be asked how they would like to be addressed. Another aspect of an inclusive health histories is to ask patients what sex was assigned at birth in addition to their current gender identity (Table 2 provides an example).19

LGBTQ patients may not feel comfortable revealing their sexual orientation to health care providers.20 However, transgender individuals, especially those in transition, should notify care providers due to possible medical issues caused by the transition.20 In the dental practice, patients who have transitioned from male to female may undergo facial feminization surgery and/or take a hormone regimen to initiate the feminization process.20 Cosmetic procedures, such as veneers and crowns, may be desired by transgender patients to feminize the teeth after facial reconstruction. Oral health professionals must treat this patient population fairly and with sensitivity.

REFERENCES

- Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG, Davis D, Escamilla-Cejudo JA. Hispanic health in the USA: a scoping review of the literature. Public Health Reviews. 2016;37:31.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Distribution of U.S. Population by Race/Ethnicity, 2010 and 2050. Available at: kff.org/disparities-policy/slide/distribution-of-u-s-population-by-raceethnicity-2010-and-2050/. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- Gallup. In US, More Adults Identifying as LGBT. Available at: gallup.com/poll/201731/lgbt-identification-rises.aspx. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- Ocegueda DR, Van Ness CJ, Hanson CL, Holt LA. Cultural competency in dental hygiene curricula. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90(Suppl3):5–14.

- The Commonwealth Fund. Cultural Competency in Healthcare: Emerging Frameworks and Practical Approaches. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/ publications/fund-reports/2002/oct/cultural-competence-in-health-care–emerging-frameworks-and-practical-approaches. Accessed December 20, 2017,

- White AA 3rd, Logghe HJ, Goodenough DA, et al. Self-awareness and cultural identity as an effort to reduce bias in medicine.J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. March 24, 2017. Epub ahead of print.

- Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, Davidoff KC. Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2016;53:488–508.

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62:271–286.

- Walls M, Gonzalez J, Gladney T, Onello E. Unconscious biases: microagressions in american indian healthcare. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:231–239.

- Ping X. Using teach back for patient education and self-management. American Nursing Today. 2012;7:3.

- White M, Garbez R, Carroll M, Brinker E, Howei-Esquivel J. Is “teach-back” associated with knowledge retention and hospital readmission in hospitalized heart failure patients? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28:137–146.

- Rose PR. Cultural Competency for the Health Professional. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Learning LLC; 2013.

- Berlin EA, Fowkes WC Jr. A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care. Application in family practice. West J Med. 1983;139:934–938.

- Mantwill S, Monestel-Umaña S, Schulz PJ. The relationship between health literacy and health disparities: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145455.

- Fisher-Owens S, Barker JC, Adams S, et al. Giving policy some teeth: routes to reducing disparities in oral health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:404–412.

- Hartsell Z. Health care illiteracy: implications for providers. JAAPA. 2005;18:41–47.

- Crum M. The US illiteracy rate hasn’t changed in 10 years. Available at: huffingtonpost.com/ 2013/ 09/06/illiteracy-rate_n_3880355.html. Accessed December 20, 2017,

- National Institues of Health. Racial and Ethnic Categories and Definitions for NIH Diversity Programs and for Other Reporting Purposes. Available at: grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-089.html. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- The Fenway Institute and Center for American Progress. Asking Patients About Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Clinical Settings. Available at: thefenwayinstitute.org/wpcontent/uploads/ COM228_SOGI_CHARN_WhitePaper.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2017.

- Koch A. Treating the Transgender Patient: a Personal Narrative. Presented at American Dental Education Association Annual Session; March 19, 2017; Long Beach, California.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2018;16(01):40-43.