Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Demystified

Following are strategies for mitigating the risk and impact of this common ailment faced by oral health professionals.

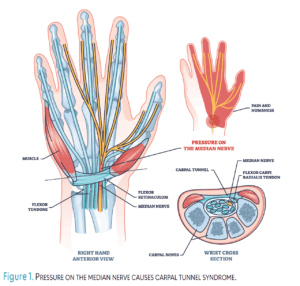

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) occurs when the median nerve, which runs through the narrow carpal tunnel in the wrist, becomes compressed (Figure 1, page 21).1,2 This nerve provides sensation to the thumb, index, middle, and part of the ring fingers, while also controlling some muscles at the base of the thumb.1 Common symptoms of CTS include numbness, tingling, or a “pins and needles” sensation, particularly in the thumb and fingers, along with pain or discomfort in the wrist, hand, or forearm. Symptoms tend to worsen at night or in the morning due to increased pressure on the median nerve from wrist flexion during sleep and fluid buildup in the wrists.3

Oral health professionals are particularly at risk due to the repetitive hand motions and fine motor skills required in their daily tasks. By understanding the causes, symptoms, and management strategies for CTS, oral health professionals can take steps to prevent its progression, minimize its impact on daily and professional activities, and overcome misconceptions that may delay timely treatment.

Prevalence

CTS is the most prevalent form of focal mononeuropathy, a condition characterized by damage or dysfunction affecting a single peripheral nerve in a localized area, accounting for approximately 90% of all neuropathy cases.1 CTS is particularly common among individuals engaged in repetitive hand movements, including oral health professionals, manual laborers, assembly line workers, typists, and those using vibrating tools.4

The incidence of CTS in the general population ranges from 1% to 5%, with women being three times more likely to develop the condition than men.5 This increased prevalence in women is likely due to anatomical differences, such as a smaller carpal tunnel, as well as hormonal factors that contribute to fluid retention, and occupational or lifestyle factors that may place additional pressure on the median nerve. Interestingly, a global literature review found no difference between the incidence of CTS in men vs women but it did report that one in seven oral health professionals is impacted by CTS.6

Obesity nearly doubles the risk of developing CTS.5 The condition is rare in children and typically manifests in adults between the ages of 40 and 60, although young adults may also develop CTS depending on the presence of certain risk factors.5

Etiology

The primary factor contributing to the development of CTS is increased pressure within the carpal tunnel.1-5 CTS is a multifactorial condition, often resulting from a combination of patient-specific, occupational, social, and environmental factors.5 As such, identifying a single cause is uncommon, unless a clear physical finding directly explains the patient’s symptoms.

While the exact mechanism behind elevated carpal tunnel pressure is not fully understood, several conditions are known to increase the risk of CTS. These risks are heightened when the structure of the carpal tunnel is altered, the body’s fluid balance is disrupted, or neuropathic factors are involved. Common risk factors for CTS include carpal dislocation or subluxation, fractures or malunion of the distal radius, wrist osteoarthritis, inflammatory or infectious arthritis, acromegaly, cysts or tumors within the tunnel, pregnancy, menopause, obesity, kidney failure, hypothyroidism, oral contraceptive use, congestive heart failure, diabetes, alcoholism, vitamin deficiency or toxicity, and exposure to toxins.7

Impact

CTS can significantly affect the ability of oral health professionals to deliver effective care, with approximately 15% experiencing this condition.8 Dentists, dental therapists, and dental hygienists rely on fine motor skills; precision; and repetitive hand movements during procedures such as scaling, polishing, and administering treatments, all of which can be compromised by the symptoms of CTS.

Numbness, tingling, and weakness in the hands may reduce grip strength and dexterity, making it difficult to handle instruments or maintain control during delicate procedures. Pain or discomfort in the wrists may also cause fatigue or require frequent breaks, reducing efficiency and potentially increasing treatment times. In severe cases, prolonged or untreated CTS may lead to diminished function or missed work, affecting patient scheduling and care continuity.9 For oral health professionals, managing CTS symptoms is essential to ensure high-quality care and prevent long-term impairment that could hinder their ability to perform critical clinical tasks.

Treatment

Treatment options for CTS depend on the severity of the condition, with conservative treatment being the first approach for mild cases. Nighttime wrist splinting is typically the initial preference, as it helps maintain a neutral wrist position, reducing pressure on the median nerve.10 Patients are advised to undergo follow-up evaluation within 1 to 2 months to assess improvement.11,12 If symptoms improve, splinting should continue; if not, additional therapies may be necessary.

Research shows that wrist splinting can relieve symptoms in 50% to 80% of mild to moderate cases, with noticeable improvement within 4 to 6 weeks.12 However, its effectiveness decreases in severe or longstanding cases. Splints that hold the wrist in a neutral position without restricting finger movement are considered the most effective, particularly custom-fitted or prefabricated splints designed specifically for CTS.12

For patients with moderate to severe CTS or those who do not respond to conservative treatments, more invasive options may be necessary. Corticosteroid injections are often used as a next step and can provide temporary relief of symptoms, though their effects typically last only a few months.10,11 If symptoms persist or worsen, carpal tunnel release surgery is the most definitive treatment.10

There are two primary surgical approaches: open release and endoscopic release, both aiming to cut the transverse carpal ligament to relieve pressure on the median nerve.10,11 The success rate for carpal tunnel release surgery is high, with approximately 70% to 90% of patients experiencing significant symptom relief and improved function.8 Endoscopic release often allows for faster recovery with less post-operative pain compared to open surgery.11

Patients undergoing endoscopic carpal tunnel release typically experience faster functional recovery, with an average return to daily activities in 16 days.8 In contrast, those who undergo open carpal tunnel release generally take longer, averaging 20 days to resume normal activities. Recovery often involves splinting and physical therapy to restore strength and function.8 For oral health professionals whose work requires repetitive hand movements, fine motor skills, and sustained grip strength, the recovery timeline may vary. Clinicians may need up to 6 weeks or more to fully regain functionality and minimize the risk of complications or setbacks.8,11

CTS can sometimes be misunderstood, leading to hesitancy in seeking treatment or disclosing symptoms. Concerns about being perceived as less capable by colleagues or employers, combined with the potential financial and professional implications of missing work, can lead to delays in diagnosis and care. Providers may downplay their symptoms or attempt to work through the pain, further postponing intervention and increasing the risk of long-term complications.13

Delayed help-seeking behavior, defined as the time between recognizing symptoms and seeking medical care, is influenced by various factors, including sociodemographic characteristics such as gender, age, and socioeconomic status.14 Psychological factors, such as uncertainty or apprehension, also play a significant role in these delays, with studies identifying these barriers as key reasons providers postpone seeking treatment.14

Encouraging open dialogue about musculoskeletal disorders, such as CTS, and reducing misconceptions around seeking care are essential steps in ensuring that healthcare providers address symptoms early, avoid prolonged damage, and maintain their ability to deliver high-quality patient care.

Preventing CTS among dental providers requires a proactive approach to ergonomics and workplace habits. Oral health professionals should prioritize maintaining neutral wrist positions during procedures, avoiding excessive flexion or extension, which can increase pressure on the median nerve. Regular breaks and stretching exercises that target the hands and wrists can reduce strain and improve circulation. Incorporating ergonomic equipment, such as well-designed dental instruments with larger handles or wrist-supporting armrests, can help minimize repetitive stress.15

Additionally, practicing proper posture, ensuring the patient chair and workstation are at appropriate heights, and frequently adjusting body positioning can alleviate unnecessary pressure on the wrists.15 Strengthening exercises for the hands, wrists, and forearms, combined with overall wellness practices like staying hydrated and maintaining a healthy weight, can also help reduce the risk of CTS.16 Even when clinicians take all the necessary precautions, they may still experience symptoms of CTS due to other risk factors, previous injuries, or anatomical features. If a clinician is struggling with CTS, they should in no way feel that their preventive efforts are ineffective, as they may simply be at a higher risk for developing these musculoskeletal conditions and may benefit from supplemental therapeutic interventions.

Conclusion

CTS remains a significant challenge for oral health professionals due to the repetitive motions and fine motor skills required in their daily tasks. Despite preventive measures, some clinicians may still develop CTS due to various risk factors, making early intervention critical for managing symptoms effectively and preventing long-term complications. Proactive ergonomic practices, regular breaks, and therapeutic interventions are essential strategies for mitigating the risk and impact of CTS, enabling dental professionals to continue delivering high-quality care. By addressing misconceptions and fostering an environment of support and understanding, the profession can empower individuals to prioritize their health, ensuring a sustainable and effective workforce dedicated to optimal patient care.

References

- Padua L, Coraci D, Erra C, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:1273-1284.

- Cleveland Clinic. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Available at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4005-carpal-tunnel-syndrome. Accessed October 27, 2025.

- Harinesan N, Silsby M, Simon NG. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol. 2024;201:61-88.

- Newington L, Harris EC, Walker-Bone K. Carpal tunnel syndrome and work. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29:440-453.

- Sevy JO, Sina RE, Varacallo M. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Available at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448179. Accessed October 27, 2025.

- Chenna D, Madi M, Kumar M, et al. Worldwide prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome among dental health care personnel – A systematic review and meta-analysis. F1000Res. 2023;12:251.

- Genova A, Dix O, Saefan A, Thakur M, Hassan A. Carpal tunnel syndrome: a review of literature. Cureus. 2020;12:e7333.

- Louie D, Earp B, Blazar P. Long-term outcomes of carpal tunnel release: a critical review of the literature. Hand (N Y). 2012;7:242-246.

- Chenn Rotaru-Zavaleanu AD, Lungulescu CV, Bunescu MG, et al. Occupational carpal tunnel syndrome: a scoping review of causes, mechanisms, diagnosis, and intervention strategies. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1407302.

- Lusa V, Karjalainen TV, Pääkkönen M, Rajamäki TJ, Jaatinen K. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;1:CD001552.

- Wang L. Guiding treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2018;29:751-760.

- Karjalainen TV, Lusa V, Page MJ, O’Connor D, Massy-Westropp N, Peters SE. Splinting for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;2:CD010003.

- Tawakul A, Alharbi MH, Althobaiti FS, et al. Awareness of carpal tunnel syndrome among adults in the western region of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023;15:e42777.

- Dubayova T, van Dijk JP, Nagyova I, et al. The impact of the intensity of fear on patient’s delay regarding health care seeking behavior: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2010;55:459-468.

- Abichandani S, Shaikh S, Nadiger R. Carpal tunnel syndrome — an occupational hazard facing dentistry. Int Dent J. 2013;63:230-236.

- Page MJ, O’Connor D, Pitt V, Massy-Westropp N. Exercise and mobilisation interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;:CD009899.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November/December 2025; 23(6):22-24.