Caries Later in Life

Diagnosis and assessment of root caries in older patients.

As longevity in many countries, including the United States, continues to increase, individuals are retaining their natural teeth for longer periods of time.1 Statistics show that in 1962, nearly 60% of Americans older than 65 were edentulous. By 1985 that percentage had decreased to 42%.2 Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES III) survey conducted between 1988 and 1991 revealed that approximately 26% of 65-year-olds to 69-year-olds and nearly 31% of 70-year-olds to 74-year-olds were edentulous.2 With this increased number of retained teeth in older adults comes an increased risk for dental caries.2 While coronal caries is also a problem root caries is the most common form of caries in older people.3

DEVELOPMENT OF ROOT CARIES

Although much is known about the development of caries on enamel, little is known about the initiation of caries on root surfaces. However, the processes are most likely similar. It was originally assumed that root caries was a distinct disease process but recent microbiological studies of root caries flora found many bacterial species, including Lactobacilli and several species of Streptococcus in both early and advanced root lesions.4

Bacteria invade the root surface laterally along the incremental lines of cementum and then penetrate the dentin (see Figure 1). Shortly after this bacterial invasion during deminerilazation, the dentinal tubules sclerose causing the collapse of the collagenous matrix that prevents direct penetration of bacteria to the pulp. Lesions tend to spread laterally and encircle the root. The resistance of sclerotic dentin to bacterial penetration may allow the matrix to remineralize under favorable conditions and may explain why root lesions are usually painless. The ability of the dentin to create a sclerotic barrier may depend on the vitality of the nearby dentin generating cells and the odontoblasts in the pulp, thus root caries may advance more rapidly in teeth with dead or diseased pulp.5 It can be assumed that in the case of xerostomia older patients will experience a higher pH value than younger patients who mostly do not experience xerostomia, therefore, root caries will prevail.

Bacteria invade the root surface laterally along the incremental lines of cementum and then penetrate the dentin (see Figure 1). Shortly after this bacterial invasion during deminerilazation, the dentinal tubules sclerose causing the collapse of the collagenous matrix that prevents direct penetration of bacteria to the pulp. Lesions tend to spread laterally and encircle the root. The resistance of sclerotic dentin to bacterial penetration may allow the matrix to remineralize under favorable conditions and may explain why root lesions are usually painless. The ability of the dentin to create a sclerotic barrier may depend on the vitality of the nearby dentin generating cells and the odontoblasts in the pulp, thus root caries may advance more rapidly in teeth with dead or diseased pulp.5 It can be assumed that in the case of xerostomia older patients will experience a higher pH value than younger patients who mostly do not experience xerostomia, therefore, root caries will prevail.

DIAGNOSIS

Root lesions are frequently difficult to detect because many appear as small, discrete lesions on a single root surface rather than circumscribing a root.6 Although most lesions occur on exposed root surfaces, approximately 15% of all root lesions are found on surfaces without gingival recession, although there is loss of periodontal attachment.6-8

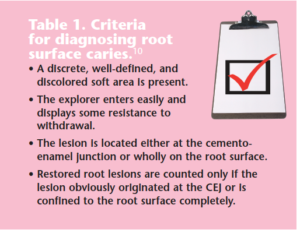

Historically, the diagnosis of root caries has been achieved through visual and tactile clinical signs that include color, contour, surface cavitation, and surface texture. Discoloration, cavitation, and/or a soft texture indicate caries. Unfortunately, visual and tactile methods do not detect caries until the lesions are in an advanced stage (Figure 2). There is also significant discrepancy between clinicians in their ability to detect caries.9 As a result, diagnostic tests are available to aid in their identification of root caries. Newer methods include scoring systems to determine the activity of lesions on root surfaces, a test to determine the presence or absence of lactic acid formed by the bacteria in plaque, and caries detection devices. See Table 1 for a list of criteria for diagnosing root surface caries.10

A scoring system is based on four characteristics of lesions. First, texture, which is described as hard, leathery, or soft and scores 0, 2, or 3, respectively. Second, surface contour, which scores smooth surfaces with no cavitation with a 1 while cavitated surfaces with irregular borders score a 2. Third, the distance between the lesion and the gingival margin is scored. A 1 is assigned to lesions that are 1 mm or more from the gingival margin and a 2 to those less than 1 mm from the gingival margin. Finally, color is scored, with dark brown or black lesions receiving a 1 and light brown or yellowish lesions a 2. The scores from the four categories are then totaled. A score of 3 to 5 indicates arrested lesions while 6 to 9 signifies active lesions.

A scoring system is based on four characteristics of lesions. First, texture, which is described as hard, leathery, or soft and scores 0, 2, or 3, respectively. Second, surface contour, which scores smooth surfaces with no cavitation with a 1 while cavitated surfaces with irregular borders score a 2. Third, the distance between the lesion and the gingival margin is scored. A 1 is assigned to lesions that are 1 mm or more from the gingival margin and a 2 to those less than 1 mm from the gingival margin. Finally, color is scored, with dark brown or black lesions receiving a 1 and light brown or yellowish lesions a 2. The scores from the four categories are then totaled. A score of 3 to 5 indicates arrested lesions while 6 to 9 signifies active lesions.

Another diagnostic test uses an impression material, which changes color from pale blue to a deep blue when it comes in contact with the lactic acid in plaque biofilm (the outer layer of plaque deposit). Bacteria such as Strep mutans and Lactobacillus form this acid, which is related to the demineralization of hard dental tissue.11 Thus, a color change in the material is thought to indicate an active caries process. While the majority of research has focused on the material’s ability to detect lactic acid in plaque biofilm on the coronal surfaces of teeth, with more research it may also become a valuable test in the diagnosis of root caries.

The root caries index (RCI), introduced in 198012, was intended to make the simple prevalence measures more specific by including the concept of teeth at risk. A tooth was considered to be at risk for root caries if enough gingival recession had occurred to expose part of the cemental surface to the oral environment. The RCI is computed by scoring root lesions and restorations and noting teeth with gingival recession. The formula appears in Table 2.

PREVALENCE

The prevalence of root caries among American adults ages 18 or older is 25.1%.13 Prevalence reaches more than 50% among men aged 65 years and older and among women aged 75 years and older.13

The average number of root lesions in Caucasians, African-Ameri cans, and Me xi can- Americans suggests that Afric an- Americans of most ages average more root lesions than do the other groups.2

Root caries seems to be a particular problem among older people of lower socio-economic status. Because of the aging of the population and increasing retention of teeth, the number of individiuals with root caries is likely to continue to grow in the future, even if the number of lesions per person shows little change. The attention of dental practitioners should be increasingly devoted to treating and preventing root caries in adults.

Risk Factors

Root caries, by definition, is strongly associated with the loss of periodontal attachment.13-18 Socio-economic status, which encompasses years of education, number of remaining teeth, use of dental services, oral hygiene levels, and preventive behavior, is a significant predisposing factor.19 People who suffer from coronal caries also seem likely to be at risk for root caries when gingival recession occurs.20 Root caries is less prevalent in areas with community water fluoridation. Individuals who are addicted to smoking, alcohol, or narcotics exhibit more root caries than nonusers because these behaviors cause xerostomia. In addition, smokeless tobacco users are more at risk because smokeless tobacco contains sugar and enhances gingival recession.

XEROSTOMIA

One of the most significant risk factors for root caries and caries in general is the prescence of xerostomia or dry mouth. Figure 3 shows an older patient with an extreme case of xerostomia. Xerostomia is common in older adults due to the number of medications taken by this population. See Table 3 for a list of medications that cause xerostomia.20,21 It also frequently affects those who have undergone radiation during cancer treatment. Other factors that cause xerostomia include anxiety or depression, HIV, AIDS, primary biliary cirrhosis, bone marrow transplantation, vasculities, chronic active hepatitis, renal dialysis, and stress. The warning signs of xerostomia are a dry, burning mouth and throat and dry cracking lips, especially in the corners. The cracks may be tender and/or bleed. Older people with xerostomia may have problems wearing dentures, especially while eating and swallowing food.1,2,20

One of the most significant risk factors for root caries and caries in general is the prescence of xerostomia or dry mouth. Figure 3 shows an older patient with an extreme case of xerostomia. Xerostomia is common in older adults due to the number of medications taken by this population. See Table 3 for a list of medications that cause xerostomia.20,21 It also frequently affects those who have undergone radiation during cancer treatment. Other factors that cause xerostomia include anxiety or depression, HIV, AIDS, primary biliary cirrhosis, bone marrow transplantation, vasculities, chronic active hepatitis, renal dialysis, and stress. The warning signs of xerostomia are a dry, burning mouth and throat and dry cracking lips, especially in the corners. The cracks may be tender and/or bleed. Older people with xerostomia may have problems wearing dentures, especially while eating and swallowing food.1,2,20

Strategies for alleviating the symptoms of xerostomia include: changing a patient’s medication regimen; the use of presciption medication to help salivary glands function better (pilocarpine and cevimeline); the use of artificial saliva; taking sips of water/ sugarless drinks throughout the day, avoiding caffeine, coffee, tea, and soda; sucking on ice chips; chewing sugarless gum or sugarless hard candy; eliminating tobacco/ alcohol use; decreasing salty snacks/ sweets; running a humidifier at night; the use of xylitol products to increase saliva flow and inhibit decay; and the use of over-thecounter mouth – rinses, oral sprays, oral lubricants, and toothpastes designed to help alleviate dry mouth.22

PRACTICAL RISK REDUCTION AND MANAGEMENT

Although it is difficult to change patterns of behavior, several practical suggestions can be offered to patients and their physicians to reduce the risk of root caries. These include improved root caries risk assessment methods and development of clinical examination protocols and strategies for prevention and treat ment. Clinicians must identify individuals who are at risk for root caries in their practices. These patients should include older persons who have moderate to severe periodontal bone loss, xerostomia, gingival recession, have poor oral hygiene, take multiple medications, have partial dentures or retained root tips, and the recently retired or unemployed.19 Figure 4 shows an older patient with root caries caused by xerostomia and the recession of gingival tissue. Examination strategies should include annual bitewing radiographs and careful examination of proximal tooth surfaces.21 Once the patient is identified as low, moderate, or high risk, strategies for prevention should include: improving oral hygiene by using electric toothbrushes if manual dexterity is poor, and the application of topical fluoride, such as prescription-strength stannous fluoride or neutral sodium fluoride.

The use of chlorhexidine mouthrinses, modification in carbohydrate intake between meals, and the use of sugar substitutes, such as sucralose, saccharin, aspartame and “diet” products, should be recommended to reduce risk factors and manage root caries.1,2 Furthermore, the use of xylitol as a substitute for sugar is also a good strategy. The use of highly acidic food or drinks such as lemon and orange juices should be taken in moderation. Finally, the physician may modify the patient’s medication to maintain both the quantity and quality of saliva.

The use of chlorhexidine mouthrinses, modification in carbohydrate intake between meals, and the use of sugar substitutes, such as sucralose, saccharin, aspartame and “diet” products, should be recommended to reduce risk factors and manage root caries.1,2 Furthermore, the use of xylitol as a substitute for sugar is also a good strategy. The use of highly acidic food or drinks such as lemon and orange juices should be taken in moderation. Finally, the physician may modify the patient’s medication to maintain both the quantity and quality of saliva.

CONCLUSION

Greater life expectancies combined with improvements in tooth retention across all age groups, have resulted in an increasing number of Americans who have retained their teeth into old age. This increase along with the increase in the percentage of teeth with recession has in turn resulted in older persons with more root surfaces at risk for caries than ever before. Clinicians must address this problem with risk management, prevention strategies, and early diagnosis.

REFERENCES

- Ekstrand K, Martignon S, Holm-Pedersen P. Development and evaluation of two root caries controlling programmes for home-based frail people older than 75 years. Gerodontology. 2008; 25:67-75.

- Saunders RH, Meyerowitz C. Dental caries in older adults. Dent Clin N Am. 2005;49:293-308.

- Arnold WH, Bietau V, Renner PO, Gaengler P. Micromorphological and micronanalytical characterization of stagnating and progressing root caries lesions. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:591-597.

- Banting DW. Diagnosis and prediction of root caries. Adv Dent Res. 1993;7:80-86.

- Burt BA, Ismail AI, Eklund SA. Root caries in an optimally fluoridated and a high-fluoride community. I Dent Res. 1986;65:1154-1158.

- Katz RV. Assessing root caries in populations: The evolution of the Root Caries Index. J Public Health Dent. 1980;40:7-16.

- Locker D, Slade GD, Leake JL. Prevalence of and factors associated with root decay in older adults in Canada. J Dent Res. 1989;68:768-772.

- Stamm JW, Banting DW, Imrey PB. Adult root caries survey of two similar communities with contrasting natural water fluoride levels. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120:143-149.

- Locker D, Leake JL. Coronal and root decay experience in older adults in Ontario, Canada. J Public Health Dent. 1993;53:158-164.

- Kitamura M, Kiyak HA, Mulligan K. Predictors of root caries in the elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986;14:34-38.

- Ringelberg ML, Gilbert GH, Antonson DE, et al. Root caries and root defects in urban and rural adults: the Florida Dental Care Study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:885-891.

- Lawrence HP, Hunt RJ, Beck JD. Three-year root caries incidence and risk modeling in older adults in North Carolina. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55:69-78.

- Steele JG, Sheiham A, Marcenes W, et al. Clinical and behavioral risk indicators for root caries in older people. Gerodontology. 2001; 18: 95- 101.

- Vehkalahti MM. Relationship between root caries and coronal decay. J Dent Res. 1987; 66: 1608-1610.

- Vehkalahti MM, Paunio JK. Occurrence of root caries in relation to dental health behavior. J Dent Res. 1988;67:911-914.

- Whelton HP, Holland TJ, O’Mullane DM. The prevalence of root surface caries amongst Irish adults. Gerodontology. 1993;10:72-75.

- Winn DM, Brunelle JA, Selwitz RH, et al. Coronal and root caries in the dentition of adults in the United States, 1988-1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(Spec No):642-651.

- Mohammad AR. Geriatric Dentistry: A Text Book. 5th ed. Montrose, Pa: Montrose Publishing Co; 2008:249-393.

- Jones J. Root caries, prevention and chemotherapy. J Dent. 1995;8:352-357.

- Fejerskov O, Luan WM, Nyvad B, Budtz-Jorgen – sen E, Holm-Pedersen P. Active and inactive root surfaces caries lesions in a selected group of 60- 80 year-old Danes. Caries Res. 1991;25:385-391.

- Ciancio SG. Medications’ impact on oral health. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1440-1448.

- Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 10th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2009; 7(11): 24, 26, 28, 30.