Addressing the Oral Health Needs of Long-Term Care Facility Residents

The implementation of a place based dental home is essential to improving and maintaining the oral health of this vulnerable patient population.

This course was published in the August 2013 issue and expires August 31, 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the status of older adult patients living in long-term care facilities (LTCFs).

- Identify the most common oral health problems faced by residents of LTCFs.

- Explain how to develop, implement, and sustain dental homes in LTCFs.

- Detail strategies for providing care in LTCFs.

Dental hygienists spend a significant amount of time with their patients, resulting in the development of long and enduring relationships and, oftentimes, feelings of responsibility for patients’ overall oral health. When an older adult enters a long-term care facility (LTCF), and is no longer able to obtain care in the traditional dental office, both the clinician and patient experience a loss. The level of daily oral hygiene that residents receive in LTCFs is frequently substandard, leading to reduced oral and systemic health. Dental homes, however, need not be limited to the private practice. The provision of dental services in LTCFs is an evolving practice that can meet the oral health care needs of these residents.

STATUS OF OLDER ADULTS IN LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIES

The 2004 National Nursing Home Survey reports that 1.5 million people live in 16,000 LTCFs in the United States. The majority of residents (88.3%) are age 65 or older. The average facility has 108 beds, with an occupancy rate of 86.3%.1 Residents of LTCFs require some form of assistance with activities of daily living, including bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and eating, and, as such, are unable to live independently.2 Fifty-one percent of residents require assistance in at least five activities of daily living. 1 The survey noted that 62.5% of LTCFs have some arrangement for dental services. These services are most often provided by individuals contracted from the community on an “as-needed” basis.1

Many residents of LTCFs have poor oral health, due to lack of professional oral health care, use of medications that may negatively impact the oral cavity, and the inability to perform adequate oral hygiene.3 Xerostomia/hyposalivation, hypersalivation, swallowing problems, periodontal diseases, and dental caries are among the most common ailments seen in these individuals.3 State reports on the oral health of LTCF residents offer valuable insight into the oral health status of this patient population.4–6 Although percentages vary, studies indicate significant unmet dental needs. Missouri studied 1,186 residents of LTCFs. Of these residents, 22% presented with severe periodontitis (as demonstrated by mobile teeth and visible roots), and 35% had dry, sticky oral tissues.4 A similar study in Kansas that looked at 540 LTCF residents found that 15% had mobile teeth, 26% presented with severe gingivitis, 31% reported dry mouth some of the time, and 17% complained of dry mouth all of the time.5 Additionally, 53% of the Kansas LTCF residents stated they had not seen a dentist in the past year, and 58% noted they had not visited a dentist in the past 3 years. A study of 265 residents in Florida LTCFs found that 79.6% of the residents presented with calculus, and 36.6% had gingivitis.6

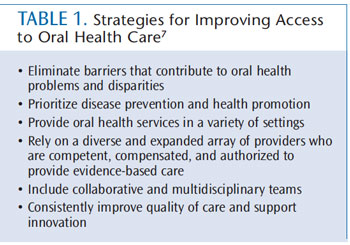

Improving the oral health status of older adults by reducing the incidence of untreated decay and periodontitis is one of the key initiatives outlined in Healthy People 2020—a program produced by the US Department of Health and Human Services that disseminates national objectives for improving the health of all Americans over a 10-year period.7 Residents of LTCFs should have access to professional dental services and be able to live without oral disease and infection. A 2011 report titled “Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations,” published by the Institute of Medicine, provides strong support for establishing place-based dental homes in LTCFs using innovative strategies.8 The report presents a vision for oral health care in the US where “everyone has access to quality oral health care throughout the life cycle.”8 Table 1 provides a list of strategies to make this vision a reality. These strategies offer an evidence-based outline for concepts that should be considered when implementing a dental home within a LTCF.

PARTNERSHIPS

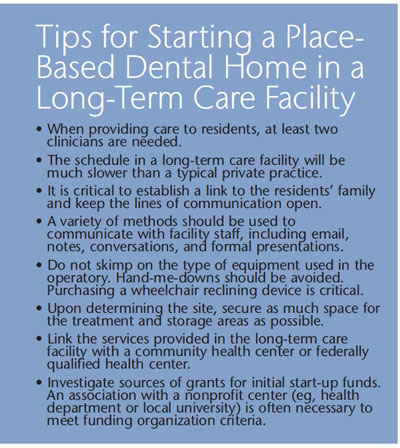

In order to create a dental home within a LTCF, funding must be secured and maintained. Partnerships can be explored through federal, state, and local governmental agencies, educational institutions, and private organizations. The Miles of Elder Smiles program, located in an Olathe, Kansas-based LTCF, began in the summer of 2012. This program was developed by faculty at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) School of Dentistry, with funding provided by the Health Care Foundation of Kansas City—a public charitable organization dedicated to improving the health of the uninsured and underserved in the greater Kansas City area. Initially, UMKC School of Dentistry partnered with the Johnson County Health Department in Kansas. The partnership expanded to include the Health Partnership Clinic (HPC), a federally funded community health center.

DIRECT ACCESS

Before dental hygienists can begin providing care in the LTCF setting, they must have an in-depth understanding of their state’s practice act. Many states allow dental hygienists to provide some form of “direct access” care. The American Dental Hygienists’ Association defines direct access as an arrangement that “allows dental hygienists the right to initiate treatment based on their assessment of a patient’s needs without the specific authorization of a dentist, treat the patient without the presence of a dentist, and maintain a provider-patient relationship.”9,10 Currently, 35 states allow dental hygienists to provide care to individuals in some type of direct access arrangement.9,10 Titles for the direct access arrangements differ by state. Since 2007, Kansas has offered dental hygienists the opportunity to provide services under the sponsorship of a dentist, but without direct supervision, in community settings through an extended care permit (ECP) I and II. This designation is attained by performing a minimum number of clinical hours under the supervision of a dentist (1,200 for ECPI and 1,800 for ECPII), which is verified by the Kansas Dental Board.

ASSESSMENT

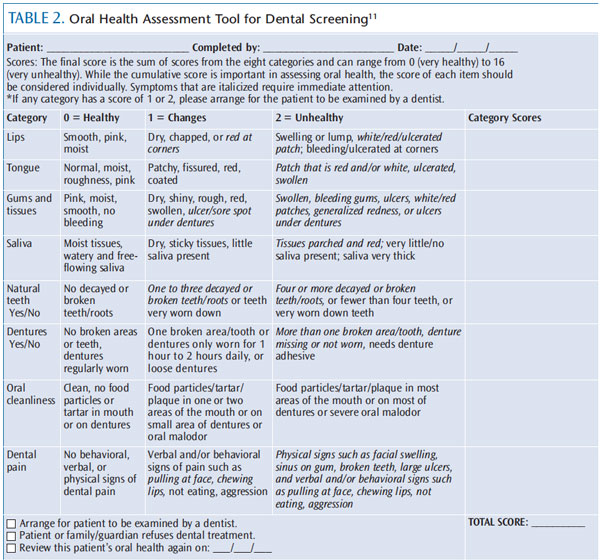

When creating a new dental home in a LTCF, the oral health of residents must first be assessed in order to determine a baseline level of disease. Many LTCF residents are covered by Medicaid and have little access to professional dental care, therefore, their oral health is often poor. The Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) for Long-Term Care is helpful in evaluating oral health status in order to create a personalized treatment plan for each patient (Table 2).11 Developed by the late Jane M. Chalmers, BDSc, MS, PhD, the OHAT is used to screen for oral health problems, but it is not a diagnostic tool and does not replace the need for an intraoral exam conducted by an oral health professional.3,11 The OHAT is indicated for use in patients with cognitive impairments, xerostomia, chronic health problems, and swallowing and/or feeding issues, as well as patients who require assistance with self-care and those who take medications or are undergoing treatment that exert negative effects on the oral cavity.3

In the Miles of Elder Smiles program, dental hygienists with ECPII conducted an oral health assessment on 96 residents to determine a baseline level of disease, and to evaluate oral hygiene and immediate dental needs. The OHAT was used as the primary measure of oral health.12 In the category of oral cleanliness, the average resident scored 1.16 (on a scale of 0 = healthy to 2 = unhealthy). This score indicated that the average resident’s mouth had “food particles, tartar, and debris” in several areas of the mouth or on denture/s, and occasional oral malodor. Twenty-six of the individuals verbally or behaviorally indicated signs of dental pain/discomfort. Four individuals presented with abscesses, broken teeth, or mouth ulcers. In the gums and tissues category, the average OHAT score was 0.77, indicating the gingiva approached a score of 1 (on a scale of 0 to 2). Gingival tissues scoring 1 could be described as dry, shiny, rough, red, and swollen.

SETTING UP THE OPERATORY

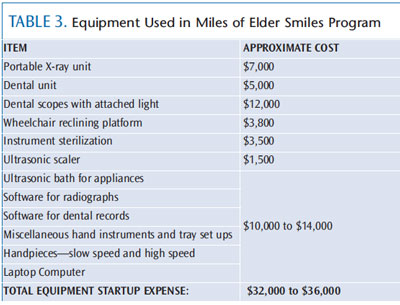

Operative and preventive services can be provided on-site to residents of LTCFs using portable dental equipment (Table 3) in a designated space. In the Miles of Elder Smiles program, the operatory was housed in the LTCF’s beauty salon, where space and sinks were available. Transferring residents from wheelchairs to portable patient chairs can be physically challenging, time consuming, and uncomfortable for patients. LTCFs may benefit from investing in a reclining wheelchair platform that allows patients to remain in their wheelchair during the appointment. In fact, this proved to be the most critical piece of equipment used in the portable dental operatory with the Miles of Elder Smiles program (Figure 1).

Elimination of patient transfer reduces the risk of mishaps, and residents appreciate the familiarity and comfort of their wheelchair during the dental appointment. Radiographs can be taken with a portable X-ray unit and stored digitally. Because state regulations vary for licensing and training of individuals using portable radiology equipment, dental hygienists should check their state practice act before proceeding with the use of radiology equipment. In Kansas, dental professionals are required to complete a specific radiation safety course. In the Miles of Elder Smiles program, the area within the LTCF that was used for the dental clinic was inspected and registered with the state before the use of radiography could begin.

THE TEAM

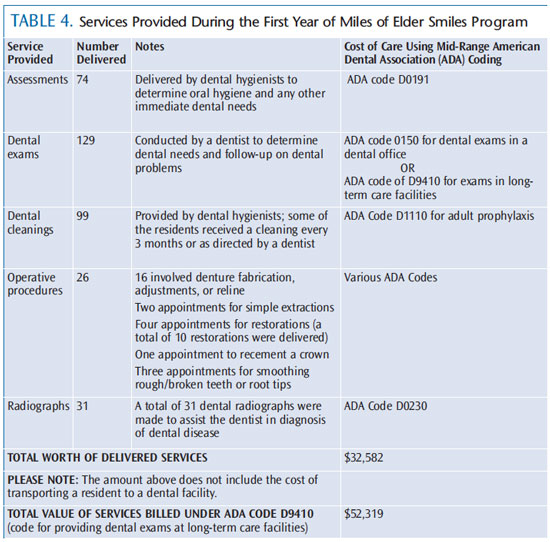

The goals of providing oral health care to this population are to: reduce plaque; prevent infection; alleviate tissue or tooth pain; maintain the ability to swallow and receive nutrition; keep lips moist; and ensure optimal function of the oral cavity.3 Each member of the dental team—dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants—can help provide effective treatment in LTCFs. Dental hygienists typically provide preventive services, such as radiographs, oral cancer exams, and scaling and root planing, on an as-needed basis. They also may manage data, communicate with LTCF staff, and maintain equipment. Dental hygienists are available on a weekly basis to provide preventive services, such as prophylaxis, to residents—some of whom may receive up to four prophylaxes per year. In the Miles of Elder Smiles program, the dentist visits the LTCF as needed (approximately 1 day per month). The dentist brings a dental assistant and provides routine restorations, simple extractions, and denture relines and adjustments. In the start-up year, a total of $32,582 (utilizing American Dental Association codes at 70% level) of dental services was provided (Table 4). The majority of these services were delivered in the latter half of the year due to initial start-up activities, which did not generate revenue. Therefore, an increase in revenue is expected as the program progresses.

All dental personnel who work in LTCFs should carry their own malpractice insurance and remain current with continuing education appropriate to dental care for older adults. In the Miles for Elder Smiles program, all dental personnel are compensated for their services on a scale comparable to private practice.

The dental team and the LTCF staff must work in concert to improve the oral health of each resident. Oral health care professionals need access to residents’ charts, in which their treatment and oral health status should be documented. Oral hygiene suggestions should be shared with LTCF staff so that they may be implemented into the resident’s self-care regimen. Dental hygienists typically provide routine follow-up and oral hygiene checks. To encourage a team approach, dental hygienists might consider presenting oral health information at LTCF staff meetings during the year. The dentist should also be available to talk with staff or residents’ families about oral health problems.

ORGANIZATION

Funding sources must be renewed in order to maintain dental homes in LTCFs. Sources include Medicaid reimbursement or private funding. Regardless, a billing system will be required. The Miles of Elder Smiles program partners with an HPC, so that the LTCF residents are patients of record for the clinic.

This allows the program to become part of the clinic’s electronic patient record system, and the clinic processes all of the billing. Electronic patient records are part of the HPC’s dental system and billing is managed through the business office of the HPC. The same quality controls for care that are part of the clinic’s dental services are in place for the LTCF program.

PROVIDING CARE

Some LTCF residents may be initially resistant to receiving dental care due to limited cognition caused by dementia or Alzheimer’s disease.

A variety of strategies for managing resistant and fearful residents can be used to address this problem.13 The behavior guidance technique known as exposure therapy gradually introduces an anxiety-producing stimulus while keeping the resident calm. As the resident learns that the stimulus is not negative, the anxiety-producing aspects of the stimulus undergo “extinction.”13,14 The first step for this therapy includes the dental professional making multiple visits to the resident’s room to establish familiarity. Once familiarity is established, the oral health professional begins the process of entering the resident’s comfort zone, ultimately accessing the mouth. This is done gradually using a variety of methods, including hand holding and conversing, and progresses to casual touching of the resident’s cheek. Eventually, the resident is comfortable with the touching process, and the clinician may ask the resident to lick his or her lips. Oftentimes, this act parts the lips and allows entry to the mouth at the corner of the lips.

This process takes time and many visits with the resident. Maintaining the dental home on-site makes this desensitization process possible. Relieving sore and dry oral conditions and simplifying daily oral hygiene routines are important facets of providing dental care to this patient population.

Soft toothbrushes should be used to protect fragile oral tissues. Power toothbrushes may be indicated for residents with limited dexterity. Toothbrushes with two heads or curved bristles may be easier to use for others. Providing alternative oral hygiene aids, such as interdental brushes, toothpicks, and floss holders, can improve plaque removal and patient compliance. Prescription fluoride dentifrice is appropriate for residents with active decay. Salivary substitutes and dry mouth rinses, gums, gels, and sprays may also assist in reducing symptoms of xerostomia.

CONCLUSION

Residents of LTCFs often present with poor oral health, resulting in pain and infections from oral diseases that could have otherwise been prevented. Lack of access to oral health care in this setting is a widespread problem that must be resolved. Establishing place-based dental homes in LTCFs provides a much-needed service for vulnerable older adults. While Miles of Elder Smiles is not unique, the lessons learned from this project are valuable and may assist other dental professionals who wish to make a difference among underserved populations in their own communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Health Care Foundation of Greater Kansas City in establishing the Miles of Elder Smiles program.

REFERENCES

- Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, Strahan GW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview.Vital Health Stat 13. 2009;167:1–155.

- Jablonski RA, Swecker T, Munro C, Grap MJ, Ligon M. Measuring the oral health of nursing homeelders. Clin Nurs Res. 2009;18:200?217.

- Johnson VB. Evidence-based practice guidelines: oral hygiene care for functionally dependent andcognitively impaired older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2012;38:11–19.

- Adult oral health assessment executive summary. Missouri Department of Health and SeniorServices. Available at: health. mo. gov/ living/ families/ oralhealth/ pdf/ Adult_ Oral_ Health_Assessment_Executive_Summary.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2013.

- Kansas Department of Health and Environment, Bureau of Oral Health. Elder smiles 2012: Asurvey of the oral health of Kansas seniors living in nursing facilities. Available at: www. oralhealthkansas.org/ pdf/ 2012%20 Elder%20 Smiles%20Report.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2013.

- Murray PE, Ede-Nichols D, Garcia-Godoy F. Oral health in Florida nursing homes. Int J Dent Hyg.2006;4:198?203.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 Topics and Objectives.Available at: www.healthy people.gov/ 2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx. Accessed July 22, 2013.

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies. Improving Accessto Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. Washington, DC: the NationalAcademies Press; 2011.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access. Available at: www.adha.org/direct-access.Accessed July 22, 2013.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access 2013, 35 states. Available at:www.adha.org/resources-docs/ 7524_ Direct_ Access_Map.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2013.

- Chalmers J, Johnson V, Tang JH, Titler MG. Evidence-based protocol: oral hygiene care forfunctionally dependent and cognitively impaired older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30:5?12.

- Chalmers JM, King PL, Spencer AJ, Wright FA, Carter KD. The oral health assessment tool—validityand reliability. Aust Dent J. 2005; 50: 191–199.

- Ellis EM, Ala’i-Rosales SS, Glenn SS, Rosales-Ruiz J, Greenspoon J. The effects of graduated exposure,modeling, and contingent social attention on tolerance to skin care products with two children withautism. Res Dev Disabil. 2006;27:585?598.

- Law CS, Blain S. Approaching the pediatric dental patient: a review of nonpharmacologicbehavior management strategies. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:703?713.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2013; 11(8): 31–35.