YACOBCHUK/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

YACOBCHUK/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Achieving an Accurate Diagnosis for Facial Paralysis

The following case report illustrates the diagnosis and management of facial paralysis caused by Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

This course was published in the December 2020 issue and expires December 2023. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the etiology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome (RHS).

- Discuss treatment strategies for this disease.

- Describe surgical interventions for managing RHS.

Oral health professionals are likely to see patients who have, or have experienced, facial paralysis, so it is important for clinicians to be aware of its potential causes. While the most common etiologies are Bell’s palsy and trauma, Ramsay Hunt syndrome (RHS) should be included in the differential diagnosis. Caused by reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus (herpes zoster/shingles) in the geniculate ganglion, RHS presents as facial nerve palsy accompanied by an erythematous vesicular rash on the ear, or in the ear canal or mouth. The rash, which is a cluster of herpetic blisters, can present before, concomitant to, or even after the onset of paralysis.1 The condition is named after neurologist James Ramsay Hunt, MD, who also described a neuralgia that accompanied the paralysis, located deep in the face or periauricular area.2 Not surprisingly, RHS can be quite uncomfortable, as it represents a unique presentation of shingles, which is notoriously painful.2 In a retrospective review of 1,507 patients with facial paralysis, Robillard et al3 identified 185 (12%) to have the Ramsay Hunt triad of symptoms—ear pain, facial paralysis, and herpetic eruptions in a cranial dermatome.

The standard-of-care treatment for Bell’s palsy and RHS is combination therapy of a steroid and antiviral medications.4,5 Treatment must begin immediately to improve the overall prognosis of the damaged nerves.6 A common tool to determine the severity of facial nerve damage is the House-Brackmann facial nerve grading scale. Patients are graded according to function of the facial nerve: grade I (100%), II (80%), III (60%), IV (40%), V (20%), and VI (0%). With severe facial palsy, an electroneurography (ENoG) evaluation is recommended to assess the integrity and conductivity of the facial nerve.7 If the ENoG reports a degeneration of 90% or greater within 14 days, it should be followed by an electromyographic (EMG) confirmation of the muscle cells’ electrical potential. One of the accepted treatment modalities is surgical intervention via facial nerve decompression (FND).8 Gantz et al8 reported that patients who undergo middle fossa FND for Bell’s palsy can experience significant improvement of normal to near normal return of facial function.

![Facial Paralysis]() Case Presentation

Case Presentation

A 47-year-old man presented to his dental office with the chief complaint of sudden onset of tingling on the left side of the tongue, which he described as “like waking up from anesthesia after a dental procedure.” He had no other complaints at this time, other than a “strange taste and/or lack of taste.” Intraoral and extraoral examinations were within normal limits, with no other signs or symptoms, except slight swelling of the submandibular glands bilaterally. The patient was in good overall health, although he did report of recovering from a “little chest cold” the previous week. The patient was referred to an otolaryngologist (ENT).

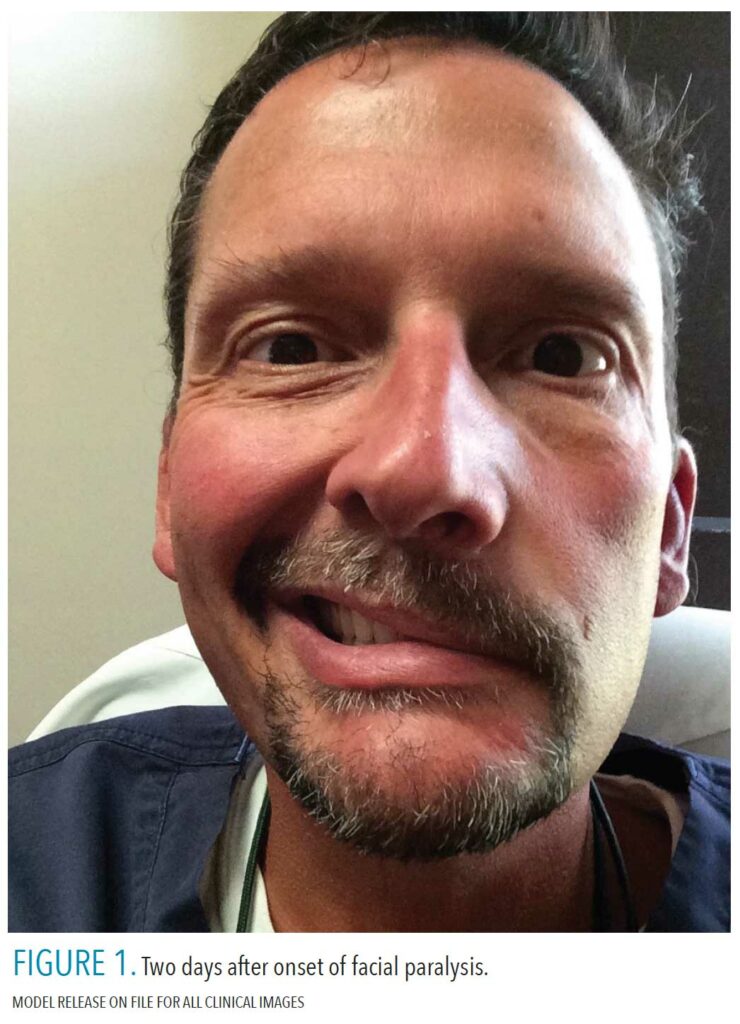

Within a few hours, the patient complained of muscle weakness and drooping of the face on the left side. The dentist made a personal call to the ENT physician, who immediately prescribed a regimen of antiviral and steroid medications (valacyclovir 1 gram tid for 10 days, and prednisone 10 mg, take 60 mg for 5 days, then taper by 10 mg for the remaining 5 days). Over the course of the next 48 hours, the patient experienced complete hemifacial paralysis, with no other symptoms (Figure 1). The patient was examined at the ENT office 3 days later and Bell’s palsy was the suspected etiology. He was scheduled for magnetic resonance imaging and Lyme’s titer/Western blot to rule out Lyme disease and other etiologies, including neoplasm. The patient also had a routine tympanometry and comprehensive audiometry threshold evaluation and speech recognition. He continued combination therapy for the next week without change.

On day 10 after onset, the patient had to travel out of town. He stated he had to tape his eye shut for protection and lubrication (Figure 2). On day 12, after completion of the combination therapy regimen, the patient began experiencing intense pain behind the ear on the affected side and called the ENT. The physician recommended seeing the patient immediately, but the patient’s flight home was not for 2 more days. On day 15 from onset, the patient was referred to an ENT/neurologist specializing in facial paralysis. During the clinical exam, herpetic vesicles were noted deep in the ear canal on and around the tympanic membrane. The vesicles were not present at the initial exam, which was on day 3 after facial paralysis. At this point, the diagnosis was confirmed as RHS. The ENT/neurologist referred the patient to a neurologist for an ENoG, EMG, and nerve conduction study on day 16. The results were > 90% degeneration of the facial nerve and no voluntary EMG motor unit potential. This typically means a 50% to 58% chance of poor facial function recovery.8 With the chance of a poor recovery and the presence of severe pain, the patient was offered the option of FND and informed about the risks and benefits associated with the surgery. The patient elected to undergo surgery.

On day 10 after onset, the patient had to travel out of town. He stated he had to tape his eye shut for protection and lubrication (Figure 2). On day 12, after completion of the combination therapy regimen, the patient began experiencing intense pain behind the ear on the affected side and called the ENT. The physician recommended seeing the patient immediately, but the patient’s flight home was not for 2 more days. On day 15 from onset, the patient was referred to an ENT/neurologist specializing in facial paralysis. During the clinical exam, herpetic vesicles were noted deep in the ear canal on and around the tympanic membrane. The vesicles were not present at the initial exam, which was on day 3 after facial paralysis. At this point, the diagnosis was confirmed as RHS. The ENT/neurologist referred the patient to a neurologist for an ENoG, EMG, and nerve conduction study on day 16. The results were > 90% degeneration of the facial nerve and no voluntary EMG motor unit potential. This typically means a 50% to 58% chance of poor facial function recovery.8 With the chance of a poor recovery and the presence of severe pain, the patient was offered the option of FND and informed about the risks and benefits associated with the surgery. The patient elected to undergo surgery.

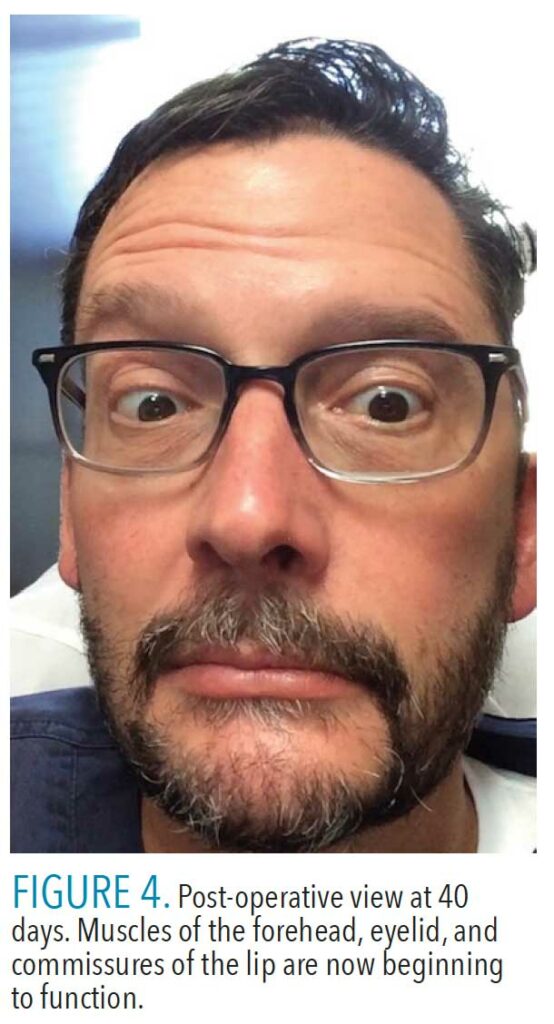

On day 18 post onset, the patient underwent FND surgery through middle cranial fossa exposure. Immediately after surgery, the patient reported that pain in the area of the mastoid process on the affected side was completely gone. The patient was treated and monitored in the hospital for the next 4 days and released. At discharge, the patient reported being able to “slightly move” the commissure of the lip and affected eyelid. Though noting no pain in the area of the mastoid process, he experienced some discomfort due to hyperacusis of hearing on the affected side. He also reported having some trismus (Figure 3, page 41). On day 12 post-surgery, the patient reported more strength returning to the forehead muscles and the ability to raise the eyebrow only slightly on the affected side. He was able to close his eyelid almost completely. The hyperacusis was still present. The patient was wearing hearing protection in the ear on affected side. He was doing passive stretching of his mandible, prescribed by the surgeon, to increase opening.

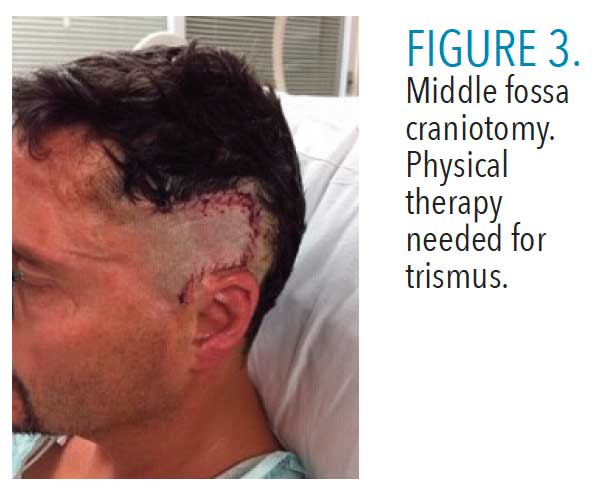

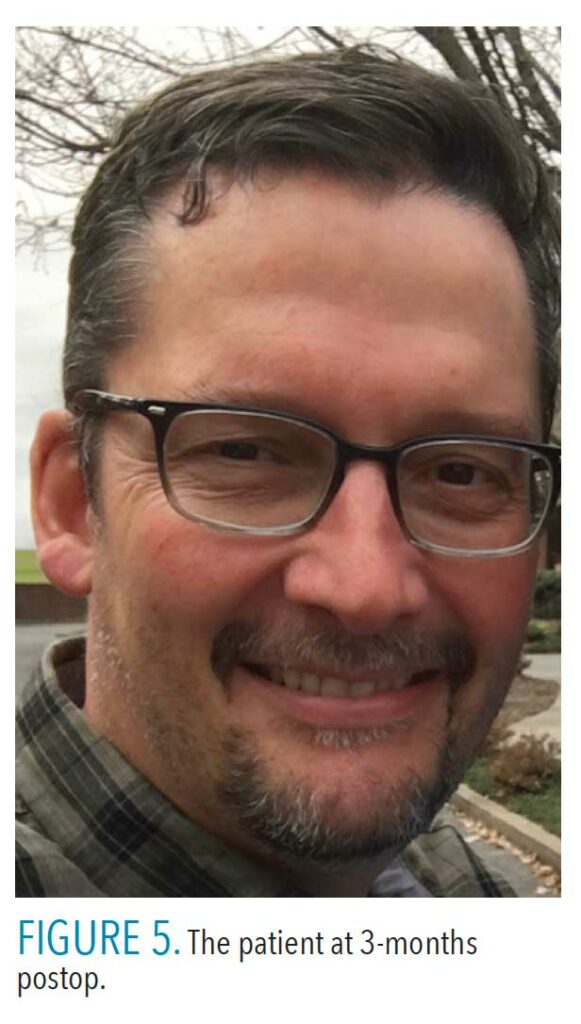

On day 40 post-surgery, patient reported the ability to completely close the eye on the affected side. The strength in the facial muscles was weak, but slowly improving. The patient had started therapy with a speech pathologist to develop an exercise regimen of facial muscles to increase facial nerve function and mitigate expected synkinesis (Figure 4), which occurs when voluntary muscle movement causes a simultaneous involuntary contraction of another muscle. At the 2-month mark, it was noted his ability to close the eyelid waxed and waned. The facial muscles continued to strengthen, but as the muscles of facial expression strengthened, they began showing some synkinesis. Specifically, when the lips moved during mastication, the eyelid would close, and, conversely, when the eyelid was shut, the muscles around the lips and cheek flexed slightly. The hyperacusis was resolved completely. By 3-months postop, the patient felt as though everything was functioning “relatively normally,” albeit with some synkinesis and drooping of the facial muscles, mostly when he was tired or not feeling well (Figure 5).

On day 40 post-surgery, patient reported the ability to completely close the eye on the affected side. The strength in the facial muscles was weak, but slowly improving. The patient had started therapy with a speech pathologist to develop an exercise regimen of facial muscles to increase facial nerve function and mitigate expected synkinesis (Figure 4), which occurs when voluntary muscle movement causes a simultaneous involuntary contraction of another muscle. At the 2-month mark, it was noted his ability to close the eyelid waxed and waned. The facial muscles continued to strengthen, but as the muscles of facial expression strengthened, they began showing some synkinesis. Specifically, when the lips moved during mastication, the eyelid would close, and, conversely, when the eyelid was shut, the muscles around the lips and cheek flexed slightly. The hyperacusis was resolved completely. By 3-months postop, the patient felt as though everything was functioning “relatively normally,” albeit with some synkinesis and drooping of the facial muscles, mostly when he was tired or not feeling well (Figure 5).

Discussion

As an aggressive disease process that causes facial nerve paralysis, inner ear dysfunction, periauricular pain, and herpetiform vesicles in or around the ear, face, tongue, or palate,9,10 RHS can lead to permanent damage to the facial nerve, permanent hearing loss, or continual inner ear issues.11 Although it presents much like Bell’s palsy, the paralysis can be more severe and patients are less likely to recover completely.10 The major difference in clinical presentation between RHS and Bell’s palsy is the presence of pain, herpes-type vesicles, and severity of paralysis. In a study by Aizawa et al,12 42 patients with RHS were followed and vesicles presented clinically as early as 27 days before and 13 days after facial paralysis. A study of 101 patients at the University of Sydney found the most common symptom was pain around the ear (90%).11 Other symptoms reported were decreased hearing (43%), facial pain other than around the ear (37%), imbalance (33%), dysgeusia (31%), and tinnitus (20%). This study also revealed that 54.5% only had pain as the initial symptom, 22.8% had only facial paralysis at first, and 2% presented with only vesicles first.11 Kanerva et al1 report that in their study, 48% presented with vesicles first, 16% concomitant with, and 36% after the onset of facial paralysis. Additionally, in 18% of these patients, the vesicles were hidden from view in the ear canal, or in the mouth.1 This large variation in presentation and asynchronous onset of symptoms makes a quick and accurate diagnosis of RHS challenging.

The patient in this case study stated that having to travel and be unavailable for daily follow-up contributed to an inability to get an appointment with a neurologist for an ENoG and EMG, which ultimately led to a delayed diagnosis. The vesicles found in the external auditory meatus most likely became clinically visible during his trip, which occurred between days 10 to 15 after onset. In a retrospective analysis of 80 patients with RHS done by Murakami et al13 from 1989 to 1995, the key to successful recovery was early diagnosis and treatment with antiviral medication and prednisone. The patients in this study were either not evaluated using an ENoG and EMG, or their use was not documented, so the severity of facial nerve degeneration was unknown. But what was remarkably significant was the day on which combination therapy was initiated. They compared patients starting medication on days 1 to 3, days 4 to 7, and days 8 to10. The incidence of complete recovery (grade I on the House-Brackmann scale) decreased proportionally to the delayed onset of medication administration.13

Timing is critical when performing FND surgery, which involves the surgical removal of the bone that is constricting the inflamed, damaged, or diseased nerve. Many times, as in this case study, the nerve is accessed by way of middle fossa craniotomy. Ideally patients with > 90% nerve degeneration and no voluntary EMG motor unit potentials who elect surgery should have the decompression on or before day 14 from onset.8 A study from the University of Iowa found a greater than 93% probability (confidence interval: 62% to 99%) of achieving a House-Brackmann grade of I (normal) or II (mild dysfunction) if surgery is performed by day 12. If the surgery is completed by day 14, these drop to 82% (confidence interval: 50% to 96%).8 Some FND surgeries have been done with some success up until day 21, but the outcome is far less predictable. The patient in this case report was aware of these risks and opted for surgery, which was performed on day 18. As of this writing, he is now 4 years and 7 months post-surgery and has a House-Brackmann grade of II (mild dysfunction).

Timing is critical when performing FND surgery, which involves the surgical removal of the bone that is constricting the inflamed, damaged, or diseased nerve. Many times, as in this case study, the nerve is accessed by way of middle fossa craniotomy. Ideally patients with > 90% nerve degeneration and no voluntary EMG motor unit potentials who elect surgery should have the decompression on or before day 14 from onset.8 A study from the University of Iowa found a greater than 93% probability (confidence interval: 62% to 99%) of achieving a House-Brackmann grade of I (normal) or II (mild dysfunction) if surgery is performed by day 12. If the surgery is completed by day 14, these drop to 82% (confidence interval: 50% to 96%).8 Some FND surgeries have been done with some success up until day 21, but the outcome is far less predictable. The patient in this case report was aware of these risks and opted for surgery, which was performed on day 18. As of this writing, he is now 4 years and 7 months post-surgery and has a House-Brackmann grade of II (mild dysfunction).

Conclusion

Dental teams are frequently the first point of contact for patients with chief complaints involving the tongue, face, or even the ear. It is therefore important for clinicians to be aware of common symptoms—such as facial paralysis and/or ear vesicles—of palsies such as RHS or Bell’s palsy, because the key to successful treatment is timing. Diagnosis and necessary referrals must take place as soon as possible after onset of symptoms. After onset of symptoms, the degree of treatment success, as measured by the level of permanent deformation and/or lack of function of the facial nerve, directly depends on the promptness of treatment.

References

- Kanerva M, Jones S, Pitkaranta A. Ramsay Hunt syndrome: characteristics and patient self-assessed long-term facial palsy outcome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277:1235–1245.

- Hunt J. On herpetic inflammations of the geniculate ganglion: a new syndrome and its complications. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1907;34:73–96.

- Robillard RB, Hilsinger RL Jr., Adour KK. Ramsay Hunt facial paralysis: clinical analyses of 185 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;95:292–297.

- Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy. Neurology. 2000;55:708–710.

- Adour KK. Combination treatment with acyclovir and prednisone for Bell palsy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:824.

- Jeon Y, Lee H. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2018;18:333–337.

- Byun H, Cho YS, Jang JY, et al. Value of electroneurography as a prognostic indicator for recovery in acute severe inflammatory facial paralysis: a prospective study of Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2526–2532.

- Gantz BJ, Rubinstein JT, Gidley P, Woodworth GG. Surgical management of Bell’s palsy. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1177–1188.

- Monsanto RD, Bittencourt AG, Bobato Neto NJ, Beilke SC, Lorenzetti FT, Salomone R. Treatment and prognosis of facial palsy on Ramsay Hunt syndrome: results based on a review of the literature. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;20:394–400.

- Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:149–154.

- Coulson S, Croxson GR, Adams R, Oey V. Prognostic factors in herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Otol Neurotol. 2011;32:1025–1030.

- Aizawa H, Ohtani F, Furuta Y, Sawa H, Fukuda S. Variable patterns of varicella-zoster virus reactivation in Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Med Virol. 2004;74:355–360.

- Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, Honda N, Gyo K, Yanagihara N. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:353–357.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2020;18(11):40-43.