A Regulatory Look At Nitrous Oxide Delivery

The dental hygiene scope of practice regarding the use of N2O-O2 differs from state to state.

Fear and anxiety remain prevalent among dental patients. These feelings are not only associated with specific dental procedures, but studies suggest that the mere thought of visiting the dentist or even sitting in the waiting room can ignite an anxious response.1,2 This fear and anxiety can stem from a variety of factors, including previous stressful or unpleasant experiences.2,3 Oral health professionals are charged with addressing and managing anxiety during dental treatment. The use of nitrous oxide is effective at addressing anxiety and fear in the dental setting. The first reported use of nitrous oxide in dentistry was in 1884, when Horace Wells, DDS, first demonstrated a “blue gassing” technique that involved the administration of pure nitrous oxide (N2O) delivered via the patient’s nose and mouth.1 When a patient turned just the right shade of blue, the gas was removed and the dental procedure was initiated.1 While Wells was credited for the initial use of N2O in dentistry, the administration technique has since evolved and includes simultaneous use of both nitrous oxide and oxygen gases (N2O-O2).

Dental hygienists are allowed to administer N2O-O2 in some states. The purpose of this article is to explore the differences in the dental hygiene scope of practice as it relates to N2O-O2 delivery and look at the variability that exists in education and training requirements, levels of supervision, and credentialing standards.

SCOPE OF PRACTICE

While state licensure requirements vary from state to state, the credential registered dental hygienist designation ensures that licensure has been obtained and the individual may legally practice dental hygiene. However, the dental hygiene scope of practice varies from state to state. Dental hygienists are responsible for knowing the rules or statutes for the states in which they practice.

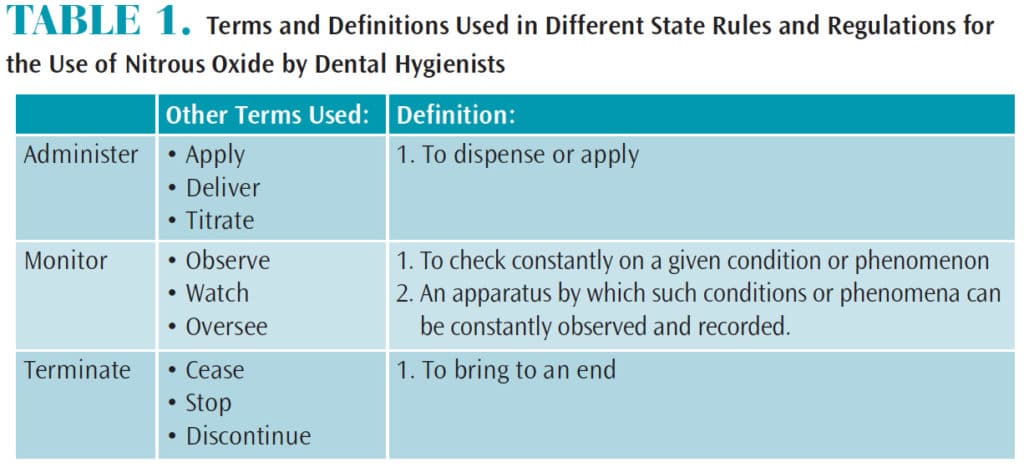

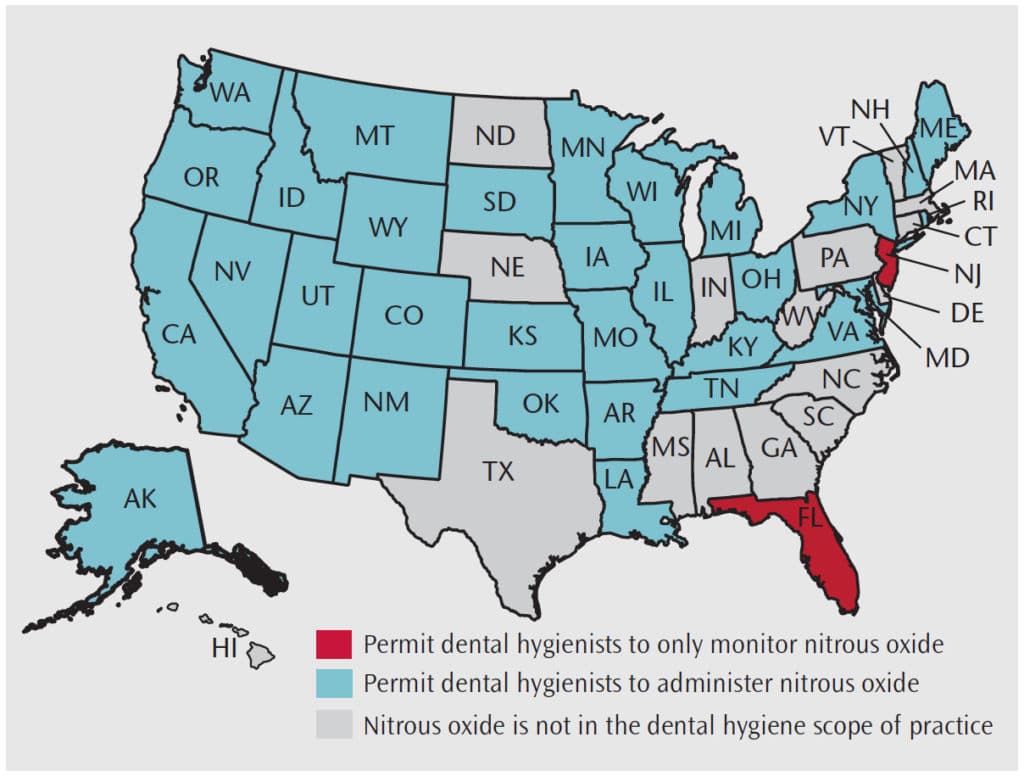

The terms administer, monitor, and terminate are used when describing the N2O-O2 procedure. Dental hygienists must understand these terms, as variations of the definitions exist within specific state’s rules and regulations (Table 1). For example, the word “monitoring” in one state may mean observing or watching a patient while N2O-O2 is being delivered, while in another state, the definition of this same term includes initiation of the flow. Currently, 32 states in the United States permit the administration of N2O-O2by licensed dental hygienists. They have the ability to start, adjust, and stop the flow of gases being administered. Two states allow dental hygienists to actively observe or monitor the patient who has been given N2O-O2, but have no administration privileges.4Sixteen states prohibit the administration or monitoring of N2O-O2 by dental hygienists.

The terms administer, monitor, and terminate are used when describing the N2O-O2 procedure. Dental hygienists must understand these terms, as variations of the definitions exist within specific state’s rules and regulations (Table 1). For example, the word “monitoring” in one state may mean observing or watching a patient while N2O-O2 is being delivered, while in another state, the definition of this same term includes initiation of the flow. Currently, 32 states in the United States permit the administration of N2O-O2by licensed dental hygienists. They have the ability to start, adjust, and stop the flow of gases being administered. Two states allow dental hygienists to actively observe or monitor the patient who has been given N2O-O2, but have no administration privileges.4Sixteen states prohibit the administration or monitoring of N2O-O2 by dental hygienists.

Washington was the first state to allow dental hygienists to administer N2O-O2 in 1971, followed by California in 1974, and Oklahoma and Oregon in 1975.5 The most recent state to allow N2O-O2 administration is Wisconsin in 2014.5 Some states, such as North Dakota, have unique scopes in that they do not allow dental hygienists to administer N2O-O2; however, they can terminate or reduce the flow rate previously administered by the dentist.6,7 In February 2017, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) revised a state map showing which states may administer or monitor N2O-O2 (Figure 1).4

LEVELS OF SUPERVISION

Weaved into the scope of practice is the level of supervision that each state requires. Typically state practice acts use the terms “direct,” “indirect,” and “general” to describe the levels of supervision needed for dental hygienists. Direct supervision typically means that the dentist needs to not only be present, but also in the room when the procedure is taking place. With indirect supervision, the dentist has authorized the procedure and must be present in the office, while general supervision permits proceeding even when the dentist is not present in the office.7 Variations of these levels of supervision also exist in some states, including prescriptive supervision and direct-access supervision.7,8 Most states require, at minimum, that the dentist be present in the office during N2O-O2administration. Only a few states allow dental hygienists to proceed independently.

EDUCATIONAL/TRAINING REQUIREMENTS

States that permit dental hygienists to administer N2O-O2 have varying educational requirements. Some states require that the education obtained must come from an accredited dental hygiene program, while others allow education from a board-approved course. The majority of states indicate the exact number of didactic hours needed, which range from 3 hours to 36 hours. In addition to a didactic component, several states require additional clinical education or experience that ranges from 2 hours to 15 hours. Four states rely on the graduating educational institution for the training requirements and do not indicate a specific number of didactic or clinical hours needed. States, such as New Mexico and Montana, do not have specific N2O-O2 educational requirements in order for dental hygienists to administer the agent. The ADHA provides a chart showing the education requirements by state at: adha.org/resourcesdocs/7515_Nitrous_Oxide_Requirements_by_State.pdf.

Many states will issue a permit or certificate to the provider upon verification of the educational or training requirements. This helps to confirm that the requirements of that state’s dental practice act have been satisfied and dental hygienists may now legally administer or monitor the agent. Dental hygienists must be aware, however, that the educational requirements of one state may not fulfill the requirements of another state. Dental hygienists can be held liable and face legal ramifications if they practice outside the legal scope of practice.

CREDENTIALING VARIABILITY

Unlike attaining a dental hygiene or local anesthesia license, a written or clinical national and state examinations are not required by all licensing boards for the use of N2O-O2. The Commission on Dental Competency Assessments offers a 50-question written examination as part of a certification process required by some states. The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA), which determines the educational standards required by dental hygiene programs, only specifies a “pain management” standard as part of the curriculum, but it does not specifically require nitrous oxide education.9 However, the individual state dental practice act determines requirements for the administration or monitoring of N2O-O2 and CODA states that educational institutions need to teach what is in the practice act. Therefore, based on the requirements of the state practice act, programs may integrate theory-based N2O-O2 education, while others may include a clinical component. Ultimately, the responsibility of nitrous oxide education lies with the individuals who seek licensure to ensure that state requirements are met and they are permitted to administer or monitor nitrous oxide.

PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY

Despite the variability in education and scope of practice, the one constant that binds dental hygienists together is their professional responsibilities as health care providers. In 1985, the ADHA developed the first clinical dental hygiene practice standards.10 As the profession evolved, these standards were revised and updated in 2008 and again in 2016.11 These standards of care provide structure for clinical decisions and help to ensure dental hygienists are delivering evidence-based, quality care.

One of the professional responsibilities that a dental hygienist is expected to uphold is to “prevent situations where patient safety and well-being could potentially be compromised.”11 Understanding the indications and relative contraindications of N2O-O2 use and being familiar with the signs and symptoms of ideal levels of conscious sedation are essential in ensuring safe delivery to patients. Dental hygienists who are permitted to administer an agent that alters patients’ current states are also morally obligated to obtain proper education and training on this subject. The ADHA’s Code of Ethics supports this standard as it relates to its core value of nonmaleficence, or do no harm.12 This may require clinicians to seek additional education beyond that of the minimum state requirements.

Dental hygienists must also “contribute to a safe, supportive, and professional work environment.”11 Though N2O-O2 has a long history of safety and efficacy, its use should not be taken lightly. Clinicians are only as good as the tools or equipment they use. While safety features exist within delivery systems, they are not without failure.13 In order to recognize these failures, clinicians need to understand how equipment works and the purpose of each component. This is essential in keeping not only patients safe, but also providers and employees working in the office.

The Code of Ethics holds dental hygienists individually accountable for maintaining high clinical standards. Professional growth is achieved via lifelong learning. Those administering N2O-O2 should pursue knowledge that continues beyond just the basics.

CONCLUSION

The profession of dental hygiene continues to advance. From its inception, just over 100 years ago, the profession has evolved from providing oral health education in schools and preventive therapies to include nonsurgical periodontal therapy and the administration of local anesthesia and nitrous oxide. This professional growth has taken many routes. The levels of education, experience, and individual competence are progressing at different speeds across the nation. Thus, dental hygienists must take their professional responsibility seriously when delivering N2O-O2. Abiding by the Code of Ethics and reviewing state rules and regulations will ensure dental hygiene providers are delivering safe care within their legal boundaries.

REFERENCES Malamed S. Dolan, J, eds. Sedation. A Guide to Patient Management. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:4-6;166–174.

- Humphris G, King K. The prevalence of dental anxiety across previous distressing experiences. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:232–236.

- White A, Giblin L, Boyd L. The prevalence of dental anxiety in dental practice settings. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91:30–34.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Nitrous Oxide Administration by Dental Hygienists 2016. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7522_Nitrous_Oxide_by_State.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Nitrous Oxide Administration by Dental Hygienists—State Chart. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7515_Nitrous_Oxide_Requirements_by_State.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018

- Hygienist Overview: Permits. North Dakota Board of Dental Examiners. Available at: nddentalboard.org/practitioners/hygienist/index.asp. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Dental Hygiene Practice Act Overview: Permitted Functions and Supervision Levels by State. Available at: adha.org/resourcesdocs/7511_Permitted_Services_Supervision_Levels_by_State.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Kracher C. The role of supervision. Perspectives on the Midlevel Practitioner. 2014;12(11):20–22.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs. Available at: ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/2016_ dh.ashx. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Standard of Applied Dental Hygiene Practice. Chicago: American Dental Hygienists’ Association; 1985.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Code of Ethics. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7611_Bylaws_and_Code_of_Ethics.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Donaldson M, Donaldson D, Quarnstrom FC. Nitrous oxide-oxygen administration: when safety features no longer are safe. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:134–143.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2018;16(3):17-19.

See how backwards Texas is!