A Closer Look at the Evidence

Recent controversy over the relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease has created confusion among both patients and health professionals.

This course was published in the July 2012 issue and expires July 2015. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Summarize the types of evidence currently available regarding the periodontal disease/cardiovascular disease relationship.

- Explain the differences between association and causation in scientific studies.

- Describe the practical implications of the research when treating patients with severe periodontal infection.

- Provide talking points regarding the periodontal disease/cardiovascular disease relationship for use during patient communication.

INTRODUCTION

Publication of the landmark paper “Association Between Dental Health and Acute Myocardial Infarction” by Mattila et al in 1989 stimulated an avalanche of interest in the associations between oral health and various systemic diseases. Lockhart et al’s recent paper “Periodontal Disease and Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: Does the Evidence Support an Independent Association” and the subsequent controversy remind us that it is important to look beyond the headlines and allow the evidence to guide our clinical practice and patient recommendations. This article, “A Closer Look at the Evidence,” provides a valuable resource to help dental professionals critically evaluate the available evidence on the relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease in order to provide patients with the best possible information. The Colgate-Palmolive Company is delighted to have provided an unrestricted educational grant to support the third article in this series created in collaboration with the American Academy of Periodontology. —Barbara Shearer, BDS, MDS, PhD, Director of Scientific Affairs, Colgate Oral Pharmaceuticals

In April, the American Heart Association (AHA) published a scientific statement in its journal circulation that provided an extensive, but not systematic, literature review of the evidence on the relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 The authors concluded that strong evidence supports an association between the two, but not causation. After publication of the statement, the AHA and the American Dental Association (ADA) published almost identical press releases with the headlines “No Proof that Gum Disease Causes Heart Disease or Stroke”2 and “No Causative Link Found Between Periodontal Disease and Heart Disease.”3 These announcements generated confusion among the public, the press, and insurance companies, as well as controversy within the medical and dental fields. While a cause-and-effect relationship between oral health and heart health has not been proven, research has indicated that the two are associated and that periodontal disease may increase the risk of CVD in some patients. Dental hygienists are in a unique position to educate patients on the relationship between heart disease and periodontal disease and to clear up any confusion caused by the AHA’s statement and press releases, which were not incorrect but highlighted specific aspects of the research.

ASSOCIATIONS AND CAUSATION

There are scientific differences in the quality or type of relationships between two conditions. Association can refer to studies reporting on a situation in a snapshot (cross-sectional) or looking back in time (case-control). For instance, if the occurrence (prevalence) of severe periodontitis is high, then the prevalence of heart disease is high in a population, and vice versa. In the AHA review, the authors found statistically significant associations between cardiovascular disease and periodontal disease in cross-sectional and case-control studies, even after control for other factors (confounders) that also cause atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), such as smoking, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. This means that periodontal disease has an effect on its own. Confounders are risk factors that could affect study results (ie, they may contribute to the cause of the resulting effect on CVD, not only the periodontal infection). This is why it is important to control for confounders in statistical analyses. In order to say whether one condition or action causes another, however, several conditions need to be true. For instance, we can only see causation in studies over time (longitudinal studies), so it is clear which condition came first. Treatment (intervention) studies are examples of potentially powerful longitudinal studies. The classic “gold standard” study is a randomized controlled trial (RCT). This would entail randomly assigning half of a group of people with (severe) periodontitis to intense treatment and management for many years, maybe decades. The other half would get no periodontal treatment during these years. For ethical and practical reasons, these studies cannot be done. Instead of direct proof, we must rely on indirect evidence showing causal relationships between periodontitis and factors that are known to cause heart disease, namely CVD risk factors.

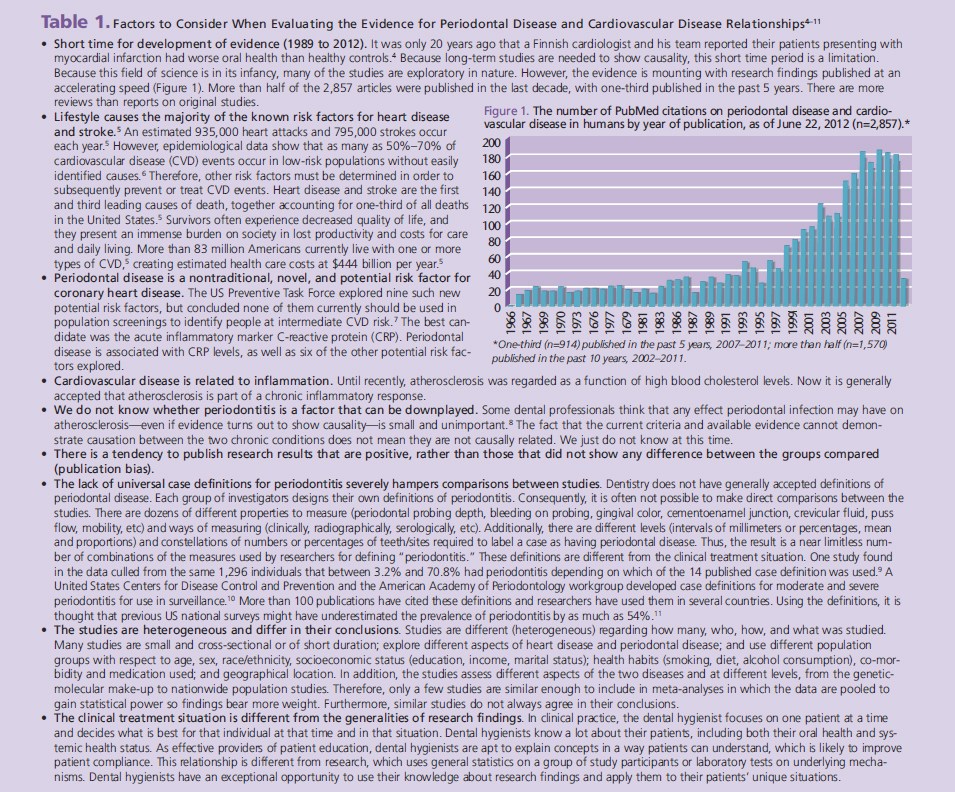

EVALUATING RESEARCH RESULTS

Many factors affect the conduct of research and their published conclusions. Table 1 provides key points to consider when evaluating the evidence on the relationship between CVD and perio dontal diseases.4–11 Additionally, periodontal destruction depends more on a person’s inflammatory reactions (host response) to the periodontal pathogens, and the inflammation they cause, than to the pathogens themselves. This is a relatively new realization that points to the possible existence of a group of highly sensitive individuals who are prone to react strongly to any irritant or infection. Both periodontal destruction and atherosclerosis are chronic conditions that take decades to develop and that exist subclinically for years before they display any symptoms (noticeable for patient) or signs (observable for the health care provider). Unfortunately, the first sign and symptom of heart disease may be a fatal myocardial infarction or stroke. For this reason, risk factors and atherosclerotic changes must be identified at the earliest possible stage. Research has recently found high blood pressure and atherosclerosis in very young people, even in preschool- aged children. Studies that provide current evidence are often observational cross-sectional or case-control designs, which cannot show causality. Many studies are small and heterogeneous regarding the population groups, such as age, race, geographic location, education, literacy, etc. They also use different case definitions of periodontitis as described in Table 1.

![]() PARAMETERS STUDIED

PARAMETERS STUDIED

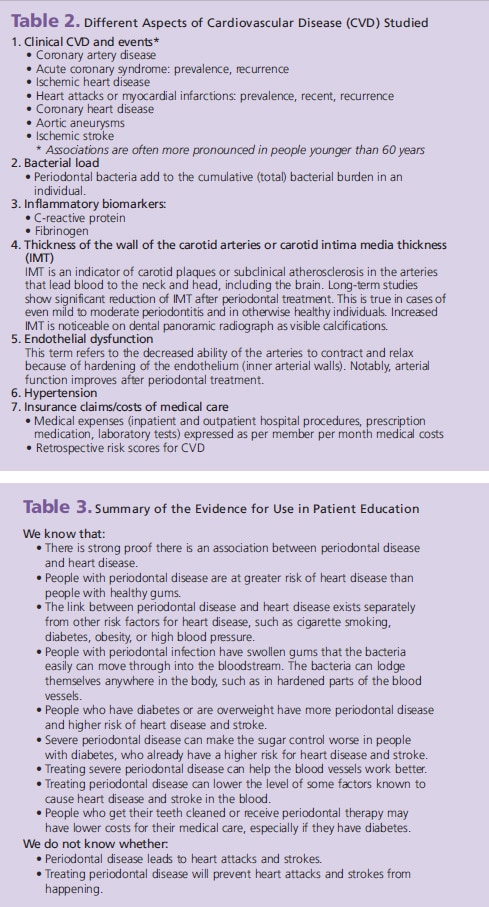

In addition to the aspects of gingivitis and periodontitis mentioned in Table 1, several studies explore partial or total tooth loss assumed to be caused by periodontal disease. Other studies explore health insurance claims on invasive dental procedures, such as periodontal treatment and extractions. One study found that among 11,869 men and women in the Scottish Health Survey who selfreported toothbrushing behavior, periodontal disease was significantly associated with CVD events. Individuals with poor oral hygiene (never/rarely brushed their teeth) had a 70% increased risk for CVD compared to those who brushed twice a day. They also had higher levels of the acute inflammatory marker C-reactive protein.12 Cardiovascular aspects are either CVD conditions or events, such as heart attacks, strokes, or risk factors that are known to contribute to CVD events. These risk factors can be either at the microbiology level or at the person level. Table 2 provides examples of the different aspects of cardiovascular disease that are commonly studied.

![]() PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Preventing periodontal disease and promoting periodontal health are essential to achieving and maintaining overall health. Dental hygienists are integral to helping patients who have active, severe periodontal infection achieve and maintain health. Dental hygienists need to continue providing periodontal therapy and self-care instructions to these patients to try to keep their periodontium as healthy and infection free as possible. This is especially important before any elective medical or dental invasive procedures are undertaken. Patients should also be advised to seek a medical checkup for heart disease or risk factors related to heart disease. These patients’ panoramic radiographs should be carefully examined for signs of calcified, thickened carotid arteries in both the right and left sides, although panoramic radiographs are not designed to screen for these calcifications. Patients with carotid calcifications could greatly benefit from referral for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular evaluation and aggressive management of vascular risk factors. Providing patients with accurate information is paramount for both their health and their regard for the dental hygienist as part of their overall “health home.” Table 3 provides a summary of what we know and what we do not know about the periodontal disease-cardiovascular disease relationship. Dental hygienists can use these points to accurately educate their patients.

CONCLUSION

A strong association exists between periodontal disease and heart disease that is not due to shared risk factors that cause both diseases, such as smoking, diabetes, and obesity. We need more studies to determine whether periodontal infection causes cardiovascular disease and whether treating periodontal disease can prevent heart disease and stroke. We do know, however, that preventing or treating periodontal infection helps maintain or improve oral health, which is an integral part of overall health. With the high prevalence of both periodontitis and cardiovascular disease, dental hygienists play an invaluable role on the team of health care professionals who make up the “health care home” for each patient. The future will show whether this important role also includes prevention of heart attack and stroke.

REFERENCES

- Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, et al. Periodontal Diseaseand Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: Does the Evidence Support an Independent Association?: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:2520–2544.

- American Heart Association. No proof that gum disease causesheart disease or stroke. Available at: www.newsroom .heart .org/ pr/ aha/_prv-no-proof-that-gum-disease-causes-232043.aspx. Accessed June 22, 2012.

- American Dental Association. AHA statement: no causative linkfound between periodontal disease and heart disease. Available at: www.ada.org/6983.aspx. Accessed June 22, 2012.

- Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, et al. Associationbetween dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298:779–781.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart disease andstroke prevention; addressing the nation’s leading killers: at a glance 2011. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ chronicdisease/ resources/ publications/AAG/dhdsp.htm. Accessed June 25, 2012.

- Jackson R, Marshall R, Kerr A, Riddell T, Wells S. QRISK or Framinghamfor predicting cardiovascular risk? BMJ. 2009;339:b2673.

- Helfand M, Buckley DI, Freeman M, et al. Emerging risk factorsfor coronary heart disease: a summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:496–507.

- Hughes S. AHA: No Evidence That Gum Disease Causes CHD.Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/762315. Accessed June 22, 2012.

- Manau C, Echeverria A, Agueda A, Guerrero A, Echeverria JJ.Periodontal disease definition may determine the association between periodontitis and pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:385–397.

- Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-basedsurveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(Suppl): 1387–1399.

- Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Dye BA. Accuracyof NHANES periodontal examination protocols. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1208–1213.

- de Oliveira C, Watt R, Hamer M. Toothbrushing, inflammation,and risk of cardiovascular disease: results from Scottish Health Survey. BMJ. 2010;340:c2451.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2012; 10(7): 11-14.