WOJCIECH_GAJDA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

WOJCIECH_GAJDA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Communication Is Key In Caries Management

Risk assessment, effective communication, and self-management goal setting are integral to supporting the oral health of children.

Dental caries is a transmissible bacterial infection1 but also a chronic biobehavioral disease.2 Modern caries management calls for customized risk-based disease prevention and management strategies.3,4 Surgical (restorative) treatment of carious lesions alone does not address the underlying disease.3 Without a change in an individual’s etiologic factors, new and recurrent caries will likely occur. Using a chronic disease management (CDM) framework can increase the likelihood that patients will receive personalized preventive and therapeutic oral healthcare, which can result in improved oral health.5 The American Dental Hygienists’ Association defines dental hygiene as “the science and practice of recognition, prevention, and treatment of oral diseases and conditions as an integral component of total health.”6 As members of the dental care team, dental hygienists are entrusted to educate and promote optimal oral health behaviors, along with providing preventive dental care. By using effective communication strategies, dental hygienists are well-positioned to engage their patients in altering their oral hygiene and dietary habits to effectively self-manage their dental disease.

CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT

CDM is a system of coordinated healthcare interventions in which patient self-care efforts are significant. CDM focuses on patient self-management strategies using evidence-based protocols developed by healthcare professionals.2 As dental caries is a chronic disease significantly influenced by social and behavioral factors, effective disease control requires personalized strategies for each patient. Historical strategies often have relied on providing general information or healthcare providers telling patients what they should or should not do. General recommendations such as “brush your teeth twice a day” and “don’t eat candy,” have had limited success.7

Patient-centered approaches, such as CDM, are more promising to engage the patient/parent/caregiver to change specific behaviors. CDM calls for close collaboration between a patient/parent/caregiver, who is engaged and informed, and a healthcare provider who is proactively promoting behavioral changes.8 CDM requires shared decision making between the professional care team and the patient/parent/caregiver to define problems, set priorities, establish goals, and create treatment plans. Dental hygienists are ideally positioned to identify the etiology of the caries process, educate the patient/parent/caregiver, provide personalized coaching and support to the patient/parent/caregiver to make behavioral changes, and provide referrals for restorative treatment as needed.

Children with early childhood caries (ECC) often require restorative treatment with sedation or general anesthesia, which have health risks9 and high costs.10 Using a CDM framework can help to prevent dental caries, arrest decay, or slow caries progression.8 In young children, successful CDM may result in the deferral of surgical treatment until they are ready to cooperate with conventional in-office treatment.11

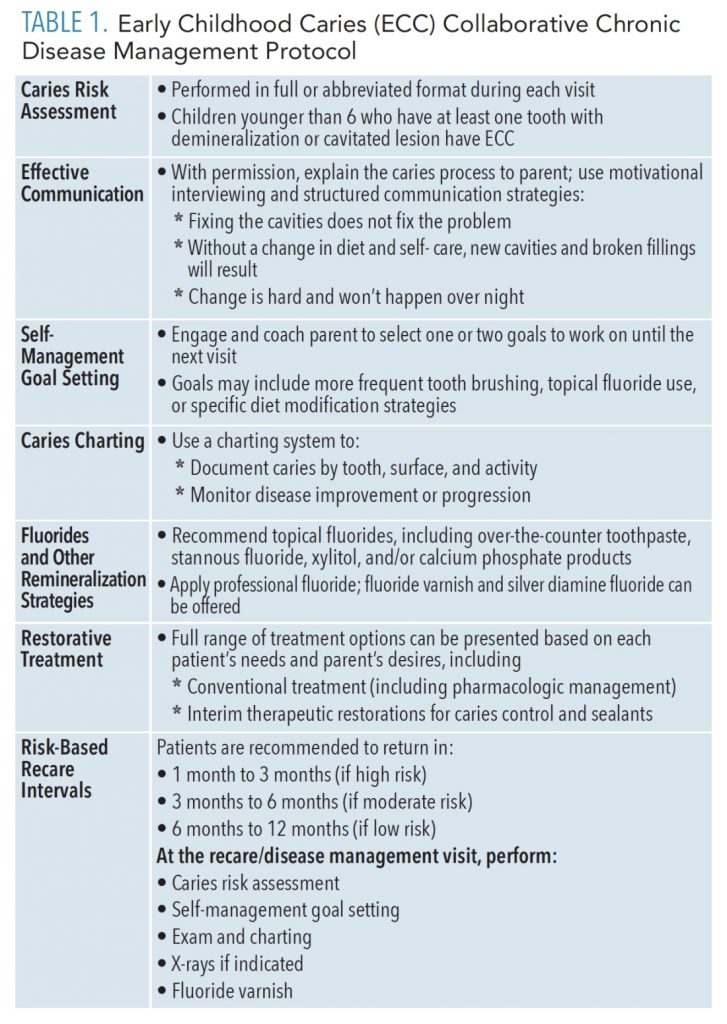

A CDM clinical protocol for the management of ECC was implemented in the DentaQuest Institute-sponsored ECC Collaborative (Table 1).5,8 The ECC Collaborative CDM protocol includes seven components: caries risk assessment (CRA), effective communication, self-management goal setting, caries charting, fluorides and other remineralizing strategies, restorative treatment as needed and desired by patient/family, and recare interval based on risk. This article will focus on the first three components.

CRA is the process of establishing the probability of developing new carious lesions over time. CRA is necessary to understand why decay occurred or a patient’s future risk for developing decay.12,13 Structured CRA forms are available from the American Dental Association,14 American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry,15 Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA),16,17 and other groups. Understanding and documenting the risk factors (eg, dietary sugar exposure—types and frequency of sugary snacks and beverages), protective factors (eg, brushing and flossing frequency, use of fluoride toothpaste) and clinical findings (eg, carious lesions by tooth, surfaces, and activity; oral hygiene status) specific to the patient during the particular visit help clinicians support patients toward behavioral change as well as assess any changes at subsequent appointments.

EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

Obtaining permission from the patient/parent/caregiver is good practice before beginning a conversation concerning the patient’s caries risk, explaining the caries process, or providing personalized coaching. In the ECC Collaborative, visual flip charts and handouts were developed to help guide the conversations with patients and parents/caregivers. A member of the care team, most often the dental hygienist, coaches the patient/parent/caregiver on self-management goal setting.8 Recognizing that change is difficult to achieve and harder to sustain, no more than one or two self-management goals—such as brushing twice a day instead of once, using a high potency fluoride toothpaste, or reducing sugar intake (eg, replacing frequent juice consumption with water—are typically set until the next visit.

MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a potentially more successful approach to helping patients achieve better oral health outcomes.7,18,19 Miller and Rollnick20 define MI as “a client–centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence.” MI is a collaborative conversation to strengthen a person’s motivation to commit to change and to empower patients/parents/caregivers to make effective day-to-day behavior modifications that impact their overall oral health.

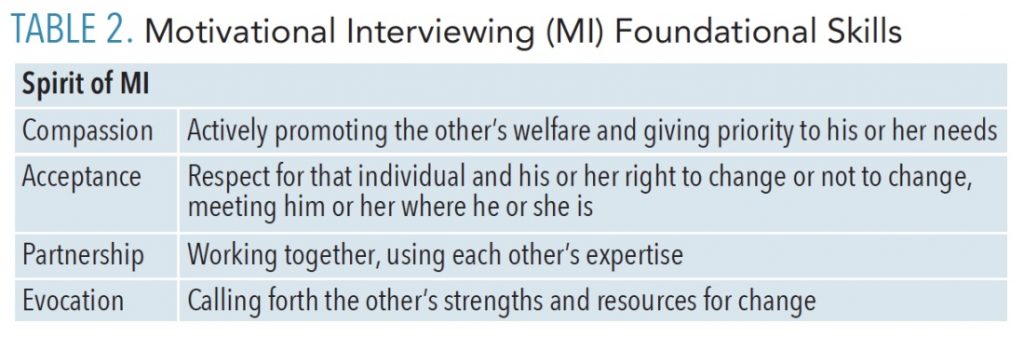

Four guiding principles constitute the spirit of MI: compassion, acceptance, partnership, and evocation (Table 2). In practice, Inglehart,13 who prefers the term motivational communication, advocates moving to a story line approach over several appointments, applying a tailored instead of general approach, and using therapeutic interventions aimed at changing behaviors. Inglehart proposes three important steps to navigate when planning how to motivate a specific oral health behavior change. Step 1 is determining which behavioral change could be targeted for change. Step 2 is understanding the affective-behavioral and cognitive status quo of the patient/parent/caregiver in order to customize communication to the patient’s situation. For example, how does the patient feel about the behavior change? What are the patient’s skills to engage in the behavior and/or which previous behaviors did the patient engage in? What does the patient know and believe about the behavior change? Step 3 is knowing which stage of change the patient is in. If the patient is not interested in a behavior change, it will not be possible to expect change.18

Four tools, represented by the acronym OARS, are used in MI to elicit behavior change: open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summaries (visit the web version of this article for a table on OARS). Asking open-ended questions allows patients to say what change they would like to make, thus encouraging “change talk.” It is not the advice of the healthcare provider but rather the desire of the patient that decides what change can be accomplished.21 Being affirmative acknowledges change and helps to build trust. Reflective listening in response to a patient’s statement allows the patient to feel heard. Summarizing ensures that the patient and care provider are on the same page.18

In the ECC Collaborative, structured communication was also used to convey empathy while sharing important concepts with patients and families. Examples include:

- Fixing the cavities does not fix the problem.

- Without a change in diet and self-care, new cavities and broken filling will result.

- Change is hard and won’t happen over night.

PATIENT EXAMPLE

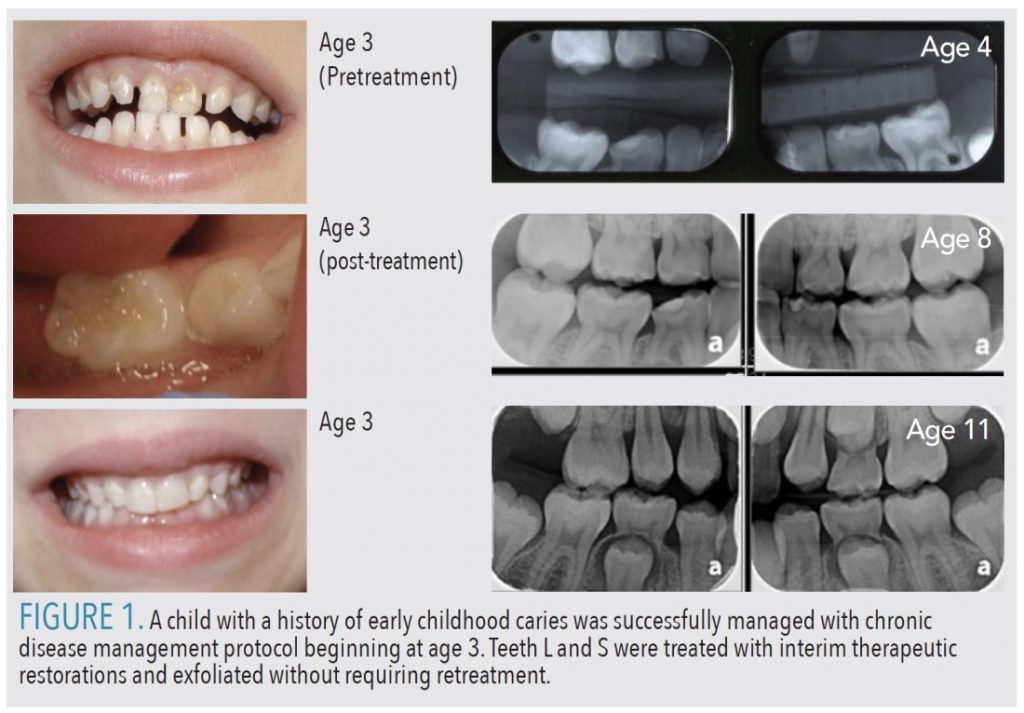

Figure 1 demonstrates images and radiographs of a patient successfully treated with the ECC Collaborative CDM protocol. The patient initially presented at age 3 with ECC and was referred for restorative treatment under general anesthesia. Her parents preferred trying the CDM protocol and chose two self-management goals: to switch from drinking diluted juice to drinking mostly water and to brush with fluoride toothpaste instead of nonfluoride (training) toothpaste. They also agreed to return for recare visits and professional fluoride varnish applications every 3 months. Over time, the patient’s carious lesions became arrested. After several “easy” recare visits, the patient allowed completion of interim restorative restorations on teeth L and S, placement of sealants, and completion of composite restorations on the maxillary incisors over time. Teeth L and S eventually exfoliated without requiring additional treatment.

THE ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST IN CDM

Dental hygienists play a pivotal role in CDM by providing risk-based patient education, coaching, support, and self-management goal setting. The components of the CDM clinical protocol are opportunities for dental hygienists to assume leadership roles in the dental setting. CDM requires professionals to work collaboratively with the patient/parent/caregiver to address specific risk factors. At the same time, patients may present for restorative treatment, but the dental hygienist may see them separately for short visits to reassess caries risk factors and provide ongoing self-management support. Using promising communication strategies, such as MI, dental hygienists are ideal members of the dental care team to engage patients in altering caries risk behaviors to improve their oral health.

References

- Featherstone JD. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:887–899.

- Edelstein BL, Ng MW. Chronic disease management strategies of early childhood caries: support from the medical and dental literature. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:281–287.

- Fontana M, Wolff M. Translating the caries management paradigm into practice: challenges and opportunities. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2011;39:702–708.

- Young DA, Lyon L, Azevedo S. The role of dental hygiene in caries management: a new paradigm. J Dent Hyg. 2010;84:121–129.

- Ng MW, Fida Z. Dental hygienist-led chronic disease management system to control early childhood caries. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2016;16:20–33.

- American Dental Hygienists Association. Dental Hygiene Diagnosis. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7111_Dental_Hygiene_Diagnosis_Position_Paper.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- Albino J, Tiwari T. Behavior change for caries prevention: understanding inconsistent results. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019:2380084419878180.

- Ng MW, Ramos-Gomez F, Lieberman M, et al. Disease management of early childhood caries: ECC Collaborative Project. Int J Dent. 2014;2014:327801.

- Sinner B, Becke K, Engelhard K. General anaesthetics and the developing brain: an overview. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:1009–1022.

- Berkowitz RJ, Amante A, Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Billings RJ, Feng C. Dental caries recurrence following clinical treatment for severe early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33:510–514.

- Meyer BD, Lee JY, Thikkurissy S, Casamassimo PS, Vann WF, Jr. An algorithm-based approach for behavior and disease management in children. Pediatr Dent. 2018;40:89–92.

- Fontana M. The clinical, environmental, and behavioral factors that foster early childhood caries: evidence for caries risk assessment. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:217–225.

- Pitts EI, Fontana M. The role of the dental hygienist in caries risk assessment. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2018;16(7):21–24.

- American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age 0-6). Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/topics_caries_under6.ashx. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2014;37:132–139.

- California Dental Association Foundation. Caries Management by Risk Assessment. Available at: cdafoundation.org/education/cambra. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crall J, Gansky SA, Slayton RL, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment appropriate for the age 1 visit (infants and toddlers). J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:687–702.

- Inglehart MR. Motivational communication in dental practices: prevention and management of caries over the life course. Dent Clin North Am. 2019;63:607–620.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Perinatal and infant oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39:208–212.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002.

- Croffoot C, Krust Bray K, Black MA, Koerber A. Eval

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2020;18(10):21-23.