The Role of Nutritional Counseling in Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy

Vital components of nutritional counseling can improve periodontal outcomes for patients when compared to instrumentation alone.

This course was published in the July/August 2025 issue and expires August 2028. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 150

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the effects of nutrients on periodontal health.

- Identify food sources of nutrients affecting periodontal health.

- Explain the role of nutritional counseling as part of nonsurgical periodontal therapy.

Nutrition plays a significant role in caries formation. However, the impact of nutrition on periodontal diseases also warrants clarification. Substantial scientific evidence supports the impact of nutrition in the growth, maintenance, and repair of the periodontium. Macronutrients and micronutrients play physiological roles in protecting the periodontium, and an imbalance of one or more nutrients can be a factor in the disruption of tissue integrity and immune response.1,2

Macronutrients

Proteins and carbohydrates are macronutrients that impact periodontal health and disease. Proteins serve as building blocks for the periodontium; they also help with tissue repair and wound healing and provide disease resistance.2-4 The destruction of alveolar bone tissue is a prominent feature of periodontal diseases. Sufficient protein intake is associated with higher bone mineral density and slower rates of bone loss, which supports periodontal healing.

Protein also has anabolic effects on bone. It may raise calcium absorption from the gut, increase bone mineralization, and improve periodontal outcomes in patients undergoing nonsurgical periodontal therapy.5,6

A sugar-enriched diet can increase gingival bleeding and is a risk indicator for mucositis and peri-implantitis.7 Sucrose and other carbohydrates serve as a food source for oral bacteria, which can increase the volume and formation rate of plaque biofilm.1 Furthermore, the high consumption of processed carbohydrates drives oxidative stress and advanced glycation end-products, which may trigger a hyperinflammatory state evidenced in periodontal diseases. Reducing the consumption of processed foods can significantly lower systemic inflammation, improving the gingival bleeding index.7

Protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) occurs when the body fails to obtain or absorb adequate amounts of protein and energy necessary for normal physiological function. It is particularly prevalent among older adults and is associated with adverse oral health outcomes, including tooth loss, dental caries, and periodontitis.3, 8,9

The occurrence of PEM during prenatal and post-natal periods may affect developing tissues or lead to irreversible changes in oral tissues. Mild to moderate protein deficiency in early development can result in smaller salivary glands and diminished salivary flow.10 This saliva is different in its protein composition, amylase, and aminopeptidase activity, compromising the immune function of saliva.1,11

When PEM occurs in early childhood, it affects the developing immune system, reducing the ability to respond to periodontal pathogens in later life.12 PEM may also increase the risk for noma (progressive necrosis) and necrotizing gingivitis (NG), conditions strongly associated with a depressed immune response due to nutritional deficiencies, stress, and infection.1,13

Micronutrients

Vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin K are key micronutrients that influence periodontal health. They are vital for maintaining periodontal tissue integrity and regulating inflammation, helping to prevent and slow the progression of periodontal diseases. Additionally, emerging evidence suggests that probiotics may also have a beneficial effect on periodontal health.

Provitamin A, or beta carotene, plays a vital role in various physiologic processes, including vision, immune response, cell differentiation and proliferation, intercellular communication, and reproduction.14,15 It is necessary for the growth of soft tissues and bones. In skeletal tissue, vitamin A is required for the resorption of old bone and synthesis of new bone. A deficiency of vitamin A is associated with an increased risk of infection and poor wound healing.1 Epidemiological research has shown that reduced plasma carotenoid levels are associated with an increased risk of periodontitis.14,16

Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, plays an integral role in the immune system response due to its high concentration in white blood cells. Vitamin C also serves as an antioxidant and protects cells and tissues against damage caused by free radicals. It is vital in collagen synthesis, the primary structural protein in connective tissue, cartilage, and bone, and, therefore, plays a vital role in wound healing.1

Vitamin C deficiency is known as scurvy, and its occurrence in the United States is usually limited to people whose diets lack fresh fruits and vegetables.17 The clinical signs of scurvy are typically related to inadequate collagen synthesis. The oral manifestations include generalized gingival swelling with spontaneous hemorrhage, ulceration, tooth mobility, and increased severity of periodontal infection and bone loss.17-19

A recent consensus report by the European Federation of Periodontology concluded that a lack of vitamin C plays a role in the onset and progression of periodontal diseases.14,20 Sufficient vitamin C intake may be crucial for the maintenance of periodontal health among older adults who have a higher prevalence of periodontal diseases.14

In the bone, vitamin K acts as a coenzyme activating vitamin K-dependent proteins, including osteocalcin. Osteoblasts synthesize osteocalcin during the mineralization phase of the bone. Osteocalcin aids calcium deposition into the mineral matrix by binding to calcium ions and hydroxyapatite crystals, regulating their size and shape.1

Vitamin K also stimulates osteoblastogenesis and inhibits osteoclastogenesis through nuclear factor-κB.21 Vitamin K deficiency may be seen in patients with malabsorption syndromes or in those whose intestinal microflora has been eliminated by long-term, broad-spectrum antibiotic use. A deficiency or inhibition of the synthesis of vitamin K leads to coagulopathy because of the inadequate synthesis of prothrombin and other clotting factors. Gingival bleeding is the oral manifestation of coagulopathy.17

Antioxidants and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Antioxidants support periodontal health by mitigating the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These oxygen-derived free radicals are generated as a result of inflammatory processes within oral tissues and surrounding biological fluids, contributing to periodontal tissue damage. By neutralizing ROS, antioxidants help reduce oxidative stress and support periodontal tissue integrity.22.23 While leukocyte-generated ROS facilitate microbial killing, ROS do not discriminate between pathogens and host tissues. Therefore, tissue injury can arise from excess plaque-induced extracellular ROS release.24 The body can neutralize the harmful effects of free radicals by producing endogenous antioxidants and those consumed through foods rich in antioxidants.25-27 Lower antioxidant intake has been significantly correlated to higher levels of periodontal diseases.28

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) are incorporated into the phospholipids of cell membranes and are involved in controlling inflammatory processes.29 The metabolism of omega-3 fatty acids produces pro-resolving lipid mediators, which block proinflammatory cytokines and produce anti-inflammatory effects.29,30 Omega-3 fatty acids also have antibacterial properties and may inhibit the activity of periodontal pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Prevotella intermedia.30,31 The results of a systemic review on the effects of omega-3 PUFAs as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal treatment in patients with periodontitis showed a reduction in periodontal probing depths and improved clinical attachment levels compared to nonsurgical periodontal treatment alone.32,33

In addition, some studies show that administering fermented dairy products containing probiotics may improve the oral microbiota, reduce the risk of periodontal diseases by reducing alveolar bone loss and attachment loss, and improve gingival health.34 Probiotics help manage periodontal disease through several mechanisms: they compete with pathogens for nutrients and adhesion sites, produce antimicrobial compounds, modulate the immune-inflammatory response, and indirectly influence the environment to reduce pathogenic activity. Furthermore, probiotic cultures may accumulate in microbial biofilms, promoting the reduction and replacement of periodontal pathogens.35

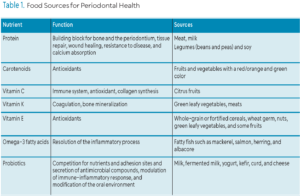

Food Sources for Periodontal Health

Table 1 lists the macro- and micronutrients, along with examples of food sources, that are essential for periodontal health. Foods with a high protein content are readily available in the US. Meat and milk food groups furnish most of the protein. Milk products are excellent protein sources but provide less iron, niacin, and vitamins E or B6 than other protein-rich foods. Legumes, such as beans and peas, along with soy products, are valuable sources of dietary protein. The consumption of fortified cereals can also enhance overall protein intake. Incorporating a variety of protein-rich foods is recommended, as each source provides unique nutritional benefits beyond protein content.1

Vitamins A, C, E, and other phytochemicals (biologically active substances found in plants) and minerals such as selenium, zinc, copper, and manganese, collectively function as antioxidants. Betacarotene or provitamin A is present in yellow, orange, and green leafy vegetables including spinach, turnip greens, and broccoli. Vitamin C is abundant in citrus fruits, juices, cantaloupe, green and red peppers, broccoli, kiwi, strawberries, and papaya. Vitamin E is available in whole-grain or fortified cereals, wheat germ, nuts, green leafy vegetables, and in smaller amounts in some fruits such as avocado, apricot, and mango.1

Omega 3 fatty acids are abundant in fatty fish such as mackerel, salmon, herring, and albacore. Most shellfish contain very little omega-3s, with the exception of oysters. The most popular n-3 PUFA supplements include fish, krill, and algal oils.32

Role of Dental Hygienists in Nutritional Counseling

Incorporating nutritional counseling into the treatment plan for nonsurgical periodontal therapy is essential for optimizing clinical outcomes. Nutritional screening includes reviewing dietary history, identifying atypical eating patterns, and considering various factors that influence food choices. This approach helps identify potential nutritional deficiencies that may adversely affect periodontal health.

Practical tools used to collect data on dietary intake include the 24-hour recall, food frequency questionnaire, and 3- to 7-day food diary. Before asking the patient to complete a diet history, explain the need for a nutrition assessment and how it relates to risk reduction in periodontal diseases.1

The diet history can be evaluated based on MyPlate and the dietary guidelines for adequacy and variety of nutrients. The website myplate.gov is the essential tool of this guidance system. An interactive nutrition education tool, the site helps individuals apply personalized dietary guidance to achieve a healthy lifestyle through better eating and increased physical activity.1 The website provides a personalized summary of servings per food group. The recommendations are based on the energy requirements to maintain a healthy or current weight and are calculated based on height, weight, age, and level of physical activity. Chairside, clinicians can quickly assess the adequacy of the patient’s dietary intake by comparing the number of servings consumed in each food group and the recommendations by myplate.gov.

One of the dental hygienist’s responsibilities is assessing nutrition history and dietary practices and integrating nutrition counseling into comprehensive dental hygiene care.1 The evidence suggests that nutritional counseling should be part of nonsurgical periodontal therapy to improve oral and systemic health.2,14 By providing dietary education to all periodontal patients, dental hygienists can facilitate tissue repair, wound healing, and resistance to infection, which can ultimately help improve outcomes of nonsurgical periodontal therapy.

Conclusion

Through the provision of nutrition counseling and the promotion of healthy dietary habits, dental hygienists play a vital role within the interdisciplinary healthcare team. By educating patients on the impact of nutrition, they contribute to the prevention of oral diseases as well as systemic conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

References

- Stegeman CA, Davis JR. The Dental Hygienist’s Guide to Nutritional Care. 5th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2018.

- Skoczek-Rubińska A, Bajerska J, Menclewicz K. Effects of fruit and vegetables intake in periodontal diseases: A systematic review. Dent Med Probl. 2018;55:431-439.

- Kotronia E, Brown H, Olia Papacosta A, et al. Poor oral health and the association with diet quality and intake in older people in two studies in the UK and USA – CORRIGENDUM. Br J Nutr. 2021;126:160.

- Woelber JP, Bremer K, Vach K, et al. Erratum to: An oral health optimized diet can reduce gingival and periodontal inflammation in humans – a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:109.

- Dodington DW, Young HE, Beaudette JR, Fritz PC, Ward WE. Improved healing after non-surgical periodontal therapy is associated with higher protein intake in patients who are non-smokers. Nutrients. 2021;13):3722.

- Kerstetter JE, O’Brien KO, Insogna KL. Dietary protein, calcium metabolism, and skeletal homeostasis revisited. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:584S-592S.

- Vilarrasa J, Pena M, Gumbau L, Monje A, Nart J. Exploring the relationship among dental caries, nutritional habits, and peri-implantitis. J Periodontol. 2021;92:1306-1316.

- Swinburn BA, Caterson I, Seidell JC, James WPT. Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:123-146.

- Mathewson SL, Azevedo PS, Gordon AL, Phillips BE, Greig CA. Overcoming protein-energy malnutrition in older adults in the residential care setting: A narrative review of causes and interventions. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;70:101401-101401.

- Sheetal A, Hiremath VK, Patil AG, Sajjansetty S, Kumar SR. Malnutrition and its oral outcome – a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:178-180.

- Enwonwu CO, Sanders C. Nutrition: impact on oral and systemic health. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2001;22(3 Spec No):12-18.

- Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR, Gondivkar RS, et al. Nutrition and oral health. Dis Mon. 2019;65:147-154.

- Russell SL, Psoter WJ, Jean-Charles G, Prophte S, Gebrian B. Protein-energy malnutrition during early childhood and periodontal disease in the permanent dentition of Haitian adolescents aged 12-19 years: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:222-229.

- Dommisch H, Kuzmanova D, Jönsson D, Grant M, Chapple I. Effect of micronutrient malnutrition on periodontal disease and periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2018;78:129-153.

- Debelo H, Novotny JA, Ferruzzi MG. Vitamin A. Advances in Nutrition. 2017;8:992–994.

- Hans M, Malik PK, Hans VM, Chug A, Kumar M. Serum levels of various vitamins in periodontal health and disease- a cross-sectional study. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2023;13:471-475.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed.Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016.

- Gandhi M, Elfeky O, Ertugrul H, Chela HK, Daglilar E. Scurvy: rediscovering a forgotten disease. Diseases. 2023;11:78.

- Chaluvaraj R, Ashley PF, Parekh S. Scurvy presenting primarily as gingival manifestation in a young child: a diagnostic dilemma. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15:e249113.

- Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Dyke TE, et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(S1):S74-S84.

- Dempster DW, Cauley JA, Bouxsein ML, Cosman F. Marcus and Feldman’s Osteoporosis. 5th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2021.

- Donald Armstrong RDS. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Protection: The Science of Free Radical Biology and Disease. 1st ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley; 2016.

- Waddington R, Moseley R, Embery G. Periodontal disease mechanisms: reactive oxygen species: a potential role in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. Oral Dis. 2000;6:138–151.

- Hirschfeld J, White PC, Milward MR, Cooper PR, Chapple ILC. Modulation of neutrophil extracellular trap and reactive oxygen species release by periodontal bacteria. Infect Immun. 2017;85:297-317.

- Malcangi G, Patano A, Ciocia AM, et al. Benefits of natural antioxidants on oral health. Antioxidants. 2023;12(6):1309.

- Agidigbi TS, Kim C. Reactive oxygen species in osteoclast differentiation and possible pharmaceutical targets of ros-mediated osteoclast diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20):3576.

- Wasti J, Wasti A, Singh R. Efficacy of antioxidants therapy on progression of periodontal disease – a randomized control trial. Indian J Dent Res. 2021;32:187-191.

- Chapple ILC, Bouchard P, Cagetti MG, et al. Interaction of lifestyle, behavior or systemic diseases with dental caries and periodontal diseases: consensus report of group 2 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:S39-S51.

- Caballero B. Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition. 4th ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023.

- Kruse AB, Kowalski CD, Leuthold S, Vach K, Ratka-Kruger P, Woelber J. What is the impact of the adjunctive use of omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19:100.

- Sun M, Zhou Z, Dong J, Zhang J, Xia Y, Shu R. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) against periodontopathic bacteria. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2016;99:196-203.

- Papathanasiou E, Alreshaid R, Araujo de Godoi M. Anti-inflammatory benefits of food ingredients in periodontal diseases. Pathogens. 2023;12:520.

- Miller LM, Piccinin FB, van der Velden U, Gomes SC. The impact of omega-3 supplements on non-surgical periodontal therapy: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2022;14:1838.

- Farias da Cruz M, Baraúna Magno M, Alves Jural L, et al. Probiotics and dairy products in dentistry: A bibliometric and critical review of randomized clinical trials. Food Res Int. 2022;157:111228.

- Nguyen T, Brody H, Lin G, et al. Probiotics, including nisin‐based probiotics, improve clinical and microbial outcomes relevant to oral and systemic diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2020;82:173-185.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July/August 2025; 23(4):32-35.